After-Hours Tour of "Noguchi's New York" Exhibit

Join an exclusive curator-led tour at NYC's Noguchi Museum!

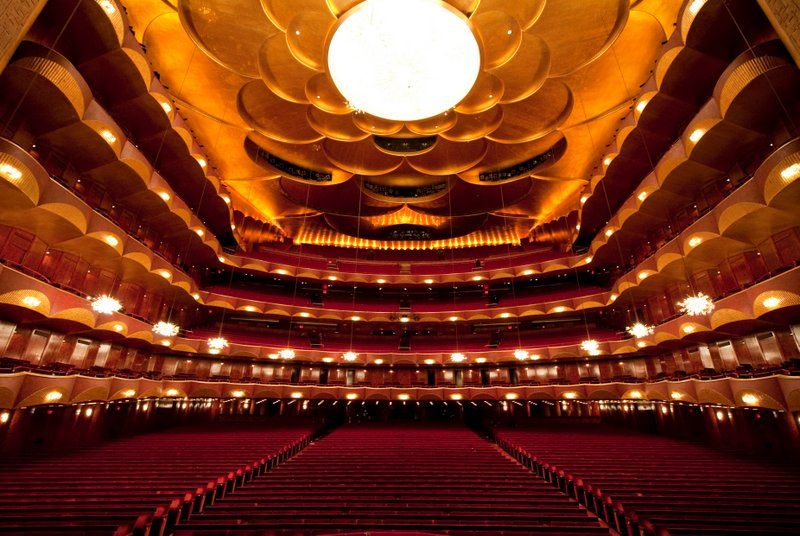

Behind the stunning productions at New York City’s Metropolitan Opera at Lincoln Center is an institution and building full of history and secrets. We recently went behind the scenes inside the Metropolitan Opera house to discover locations the public rarely gets a glimpse of – places that truly make the Met Opera come to life. Inside, approximately 1,800 people work to continue the Met Opera’s operatic tradition, producing new takes on classic operas as well as experimental works.

From an armory to a climate-controlled archive, here are 15 secrets about the Met Opera to discover:

The Metropolitan Opera house at Lincoln Center has a capacity of 3,995 people including standing room, the largest capacity of any opera house in the world. As a point of reference, the Sydney Opera House can seat up to 2,679 and the Paris Opera Garnier can seat 1,900.

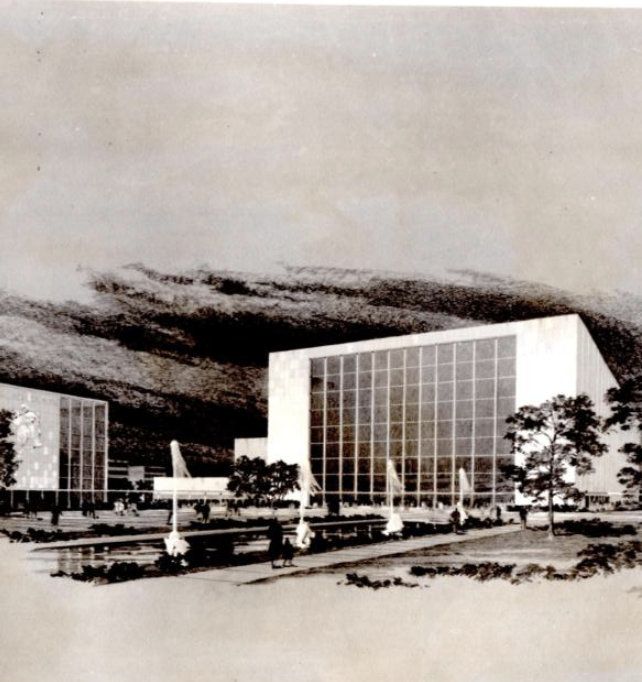

The Metropolitan Opera house was designed by Wallace Harrison, the architect also behind the Rockefeller Center complex. The resulting structure was the culmination of competing design interests, a compromise between the Metropolitan Opera House Company which wanted a more traditional opera house design and the other Lincoln Center architects who favored a Modernist look for the arts center as a whole. Harrison went through forty-two other possible designs.

Construction began in 1963 and the first public performance at the new opera house took place on April 11, 1966 with Giacomo Puccini’s La fanciulla del West.

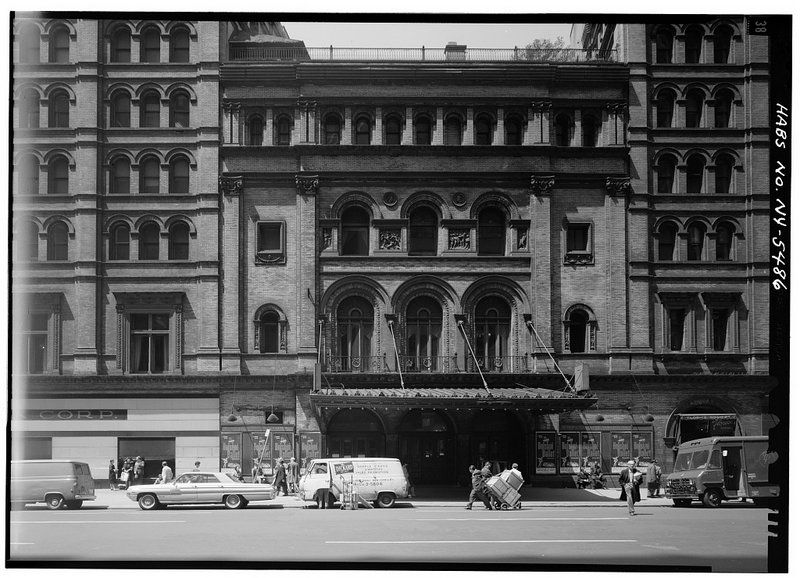

Old Metropolitan Opera House in 1966. Image from The Library of Congress.

Old Metropolitan Opera House in 1966. Image from The Library of Congress.

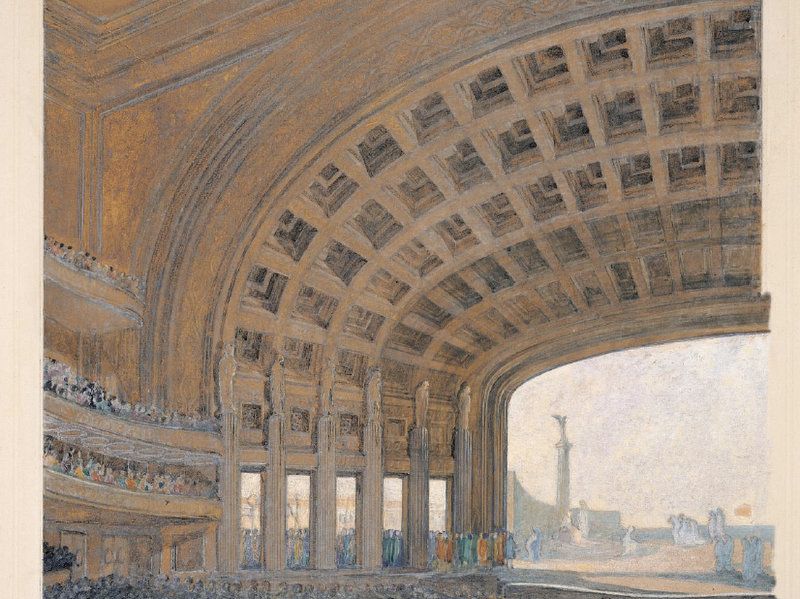

The Metropolitan Opera’s first home opened in 1883 on 39th Street and Broadway, then in the midst of the bustling theater district. It was an opulent opera house, befitting of the Gilded Age set that would have been in attendance. In fact, the Metropolitan Opera was founded by a group that included the Vanderbilts, the Roosevelts, and J. P. Morgan, as an alternative to The Academy of Music, which was located on 14th Street. The Academy, mentioned in much detail in Edith Wharton’s The Age of Innocence, was an elite, exclusive concert hall for New York City’s upper crust – the original 400 families. But downtown was becoming less desirable and the city’s new class of industrialists wanted an opera house closer to their new mansions that would be welcoming to them.

The original architect of the Met Opera on 39th Street was Josiah Cleveland Cady, who also designed the south face of the American Museum of Natural History, but a fire in 1892 led to a complete interior redesign by the famed duo Carrere and Hastings, who also designed the fare houses along the first subway line. Carrere and Hastings created an auditorium of gold with a proscenium, the largest in America at the time, that was inscribed with the names of six composers: Beethoven, Gluck, Gounod, Mozart, Verdi, and Wagner.

The Metropolitan Opera house stage is one of the most technologically advanced in the world, measuring 80 feet x 101 feet, featuring seven hydraulically operated elevators. This allows for complex staging and productions, with the possibility to preset scenery and raise it to different levels. There are fifty trap doors on the stage that are used for entrances and exits, and the appearance of props and scenery from below.

The rear and side working areas of the stage are equipped with wagons—platforms that can slide onto the main stage, bearing complete sets up to 30 feet high. The rear wagon also features a turntable, 57 feet in diameter, which can make a complete revolution in two minutes while rolling forward. For those that have seen Pelléas and Mélisande, you would have seen this turntable as a primary feature on center stage.

One hundred and ten feet above the stage—the equivalent of a ten-story building—the fly system is located. It consists of 109 pipes to “fly,” or hang, curtains, drops, and scrims (a mesh-like material used to create transformation effects).

According to the Metropolitan Opera, the main, rear, and side stages cover an area six times larger than the old Met Opera House on 39th Street and Broadway. At the stage level, the backstage is 43,000 square feet. The side stages take up another 20,300 square feet.

The spaces that support the Metropolitan Opera house productions are equally as impressive as the front of house spaces, but they go far beyond the backstage and side stage area. In fact, the Metropolitan Opera back of house goes down three levels below the stage, including C level which contains the rehearsal rooms along with 16,400 square feet of storage.

In addition, if you’ve been to the opera, you know there is often a lot of fighting going on. In the back of the house, there is an armory filled floor to ceiling with weapons of different types and eras. Here you’ll find swords, guns, cross bows, lances, and even a medieval wrecking ball.

Perhaps the most bustling area of the back of house is the costume shop, which has the feel of a European fashion house atelier. Large windows on the fourth floor flood light into the two-section space where 50 to 110 designers are at work, the numbers dependent on the production. Over the course of a season, the costume shop makes approximately 1,600 pieces of clothing and 50,000 millinery pieces, which include hats, crowns and headgear.

Five people work in the wig shop weaving wigs all made of real human hair or from Tibetan yak hair for white wigs. Each wig requires 35 hours of handwork. On the shelves are not only the wigs, but also the head models for the artists on which the artisans weave and style the wigs. A separate room next door stores wigs of the current productions.

Scenic shop at the Metropolitan Opera House

Scenic shop at the Metropolitan Opera House

The impressive sets at the Metropolitan Opera are built inside the opera house in a 9,400 square foot carpentry shop and a 4,800 scenic shop and in the Bronx, where there’s a 9,200 square foot scenic shop on 141st Street and a 34,000 square foot carpentry and scenic shop at 186th Street. Sets are designed to last 15 to 20 years, accounting for the assembling and disassembling before and after every performance or stage rehearsal.

“The Triumph of Music” (left) and “The Sources of Music” (right)

“The Triumph of Music” (left) and “The Sources of Music” (right)

Marc Chagall was commissioned to create two murals, along with the set design and costumes for the 1966 production of Mozart’s The Magic Flute. The two large paintings, The Sources of Music and The Triumphs of Music, hang above the Grand Tier level and can be viewed best from the restaurant.

The two murals were accidentally hung in reverse placement from what Chagall initially intended. As scholar Jackie Wullschlager notes in her biography of the artist, Chagall reported that upon seeing the murals in their reversed state, he “yelled as I never have before. My mother, when she gave birth to her children, didn’t yell as much. I could doubtless be heard all over Lincoln Square.” However, true to the unwritten manifesto that is Chagall’s work, eventually he decided he liked the placement, and in fact, preferred it to his original vision.

Poker games in the pit orchestra lounge are a part of Met Opera lore. The archivists believe the poker games date all the way back to the Met Opera’s first off-season tour (by train!) in 1884. The games, which take place between acts and during intermission are quick but intense, with musicians playing in tuxedos and concert dress. In January 1998, the Wall Street Journal published an article exclusively about the famed Met Opera poker games, entitled “At the Met Opera, It’s Not Over Until the Fat Man Folds” and reported that Pavarotti played once and lost.

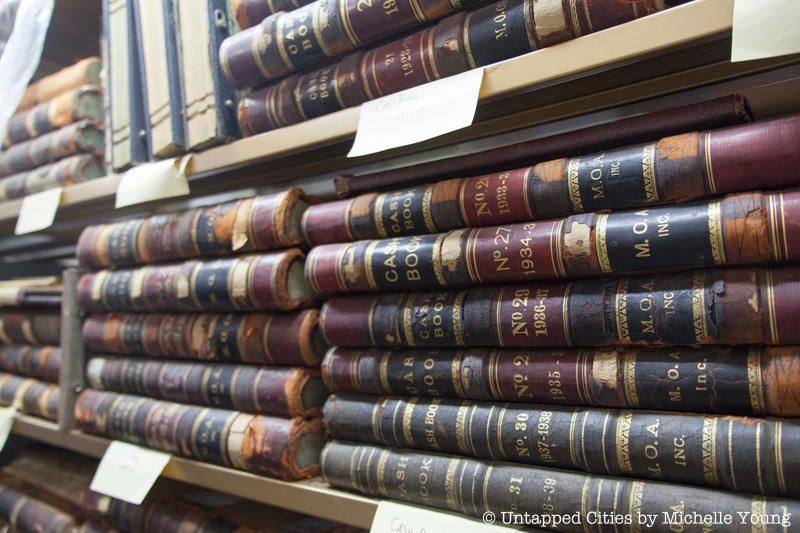

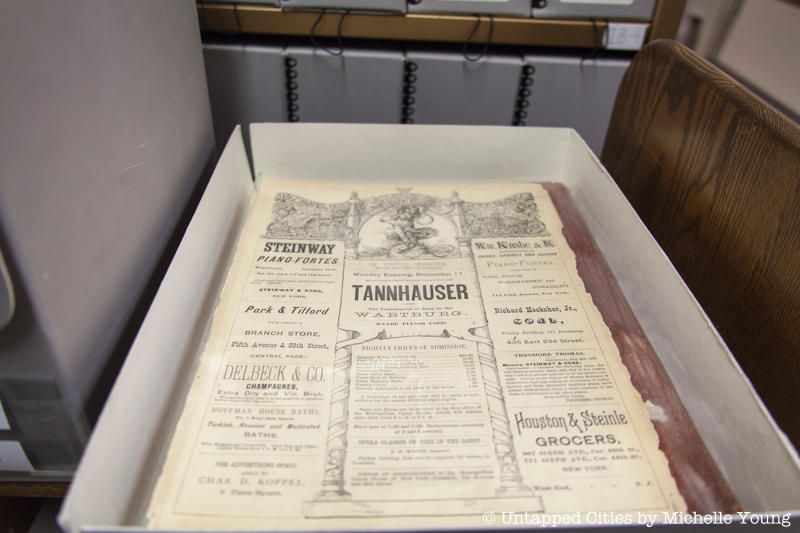

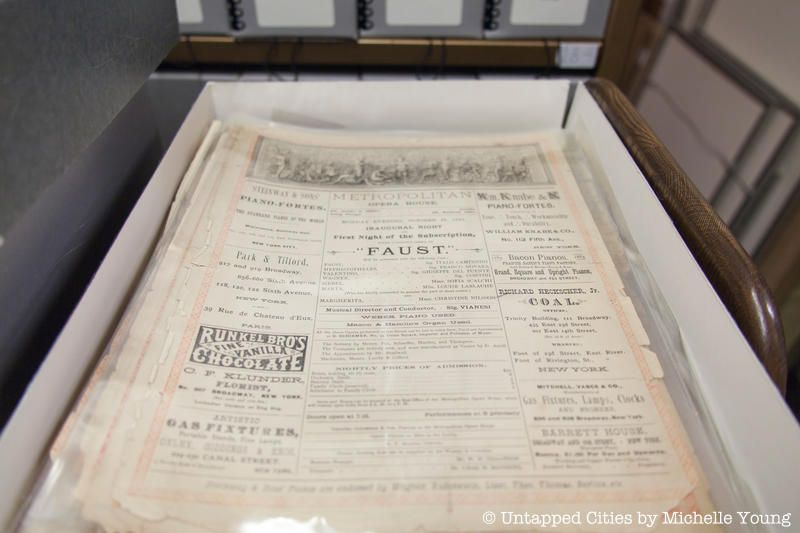

On level A, one of the below stage levels is the Metropolitan Opera archives, led by Peter Clark, the Director of Archives. The archives were first established in 1957 by Mrs. John DeWitt Peltz, a volunteer. She went into the basement of the old Metropolitan Opera house, saved boxes of materials that had been stored there haphazardly for years and organized them. Included in her finds were the opening night program from 1883 and minutes from the 1880 meeting when the board decided to build a new opera house.

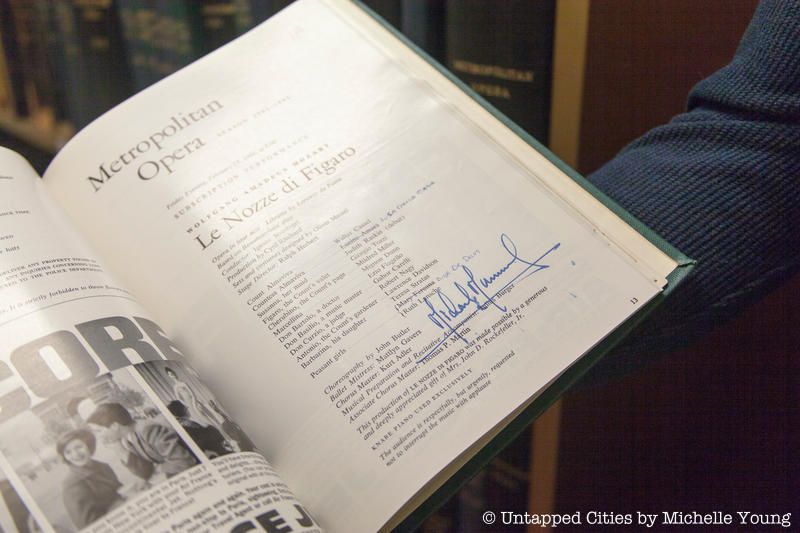

In 1981, the Met formally established an Archives department and hired Robert Tuggle to run it. The archives includes a climate controlled area that stores costumes, artist ledgers, cash books, and many other items. Almost every single program since 1883 is in the archive (there have been more than 27,000 performances since then). Costumes are stored in boxes in the climate controlled area, with large donations from the families of Enrico Caruso and Kirsten Flagstad. According to the archive, “the acquisition of costumes, once haphazard…is now systematic with important examples entering the collection as productions are retired.”

The Metropolitan Archive is also actively digitizing its archives, an initiative led by John Tomasicchio, the digital archive manager. He showed us around the climate controlled archive:

By 1967, 39th Street opera house would be razed to the ground despite a fierce landmarking effort by the community and city leaders including New York City Mayor Lindsay and Governor Nelson Rockefeller, as well as lawmakers in Albany. As the Metropolitan Opera archivists explain, within a quarter of a century, it became clear that the original building was “inadequate for producing a long season of opera on a grand scale. Though the auditorium was elegant and opulent, almost no other feature of the house met the basic needs of the performing company. Even the auditorium offered far too few full view seats, and the backstage spaces were completely insufficient. Between 1908 and 1955, the search for a site to build a new house was nearly constant.”

In 1955, the development of a multi-discipline performing arts center at Lincoln Center offered the first viable alternative new location for the Metropolitan Opera. The urban renewal project would demolish the neighborhood of San Juan Hill, where West Side Story was filmed. Ironically, along with the move, The Metropolitan Opera Management sued to have their own opera house razed. The Met Opera needed the income from the lease of a new office building on the site and also feared potential competition might arise if a new opera company took over the existing opera house.

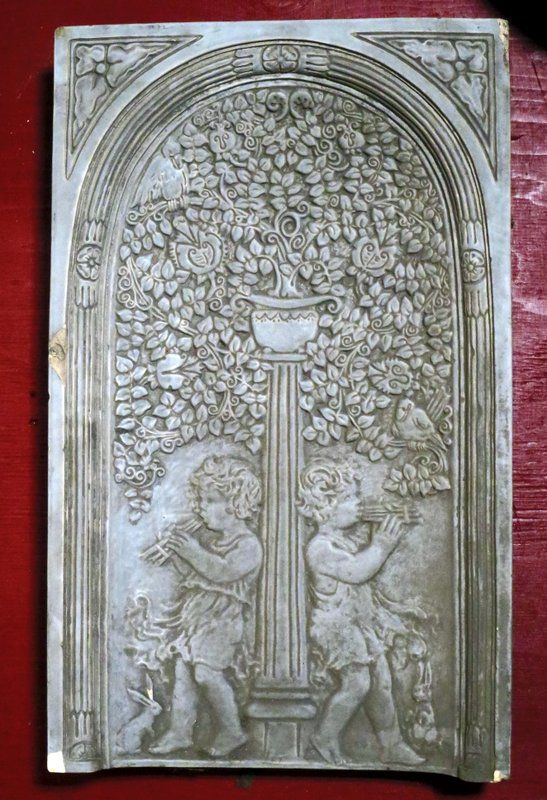

Within the Met Opera archive are pieces of the original Metropolitan Opera house at 39th Street, such as portions of the ornamented plasterwork, vintage lightbulbs, the stage, damask from the box seats, and a sign board. There are also pieces of the gold curtains from over the years, numerous door knobs, light fixtures and bricks, the box chair of Rudolph Bing (General Manager of the Met Opera 1950-1972), a large piece from the proscenium, and an original marble fountain.

Peter Clark, the Director of Archives tells us, “Sometimes people call and offer me pieces of it that were sold off by the demolition company in 1966,” and you can see from the comments on our previous article about the old Met Opera, there are more pieces out there.

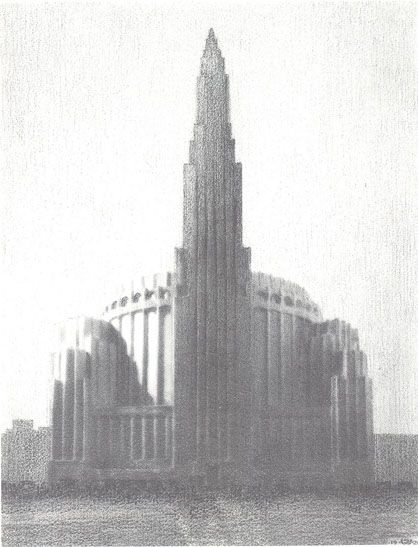

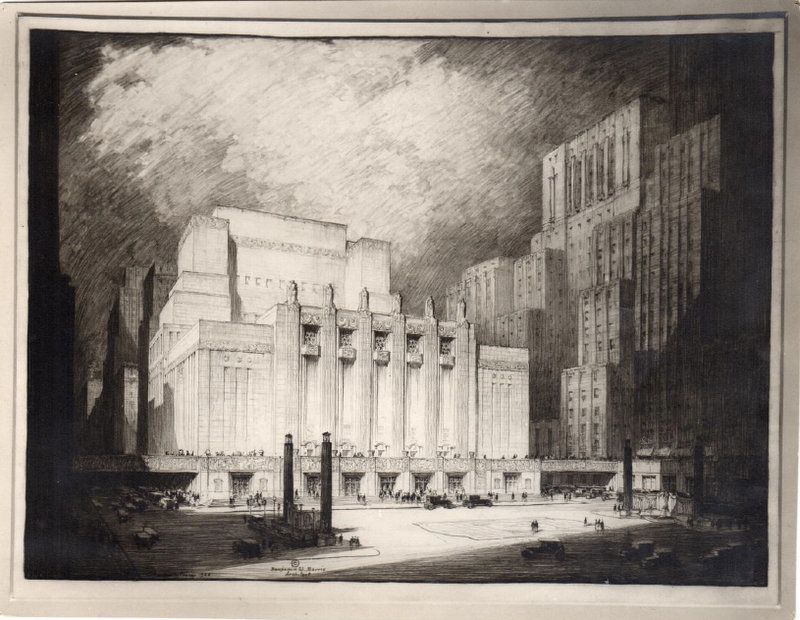

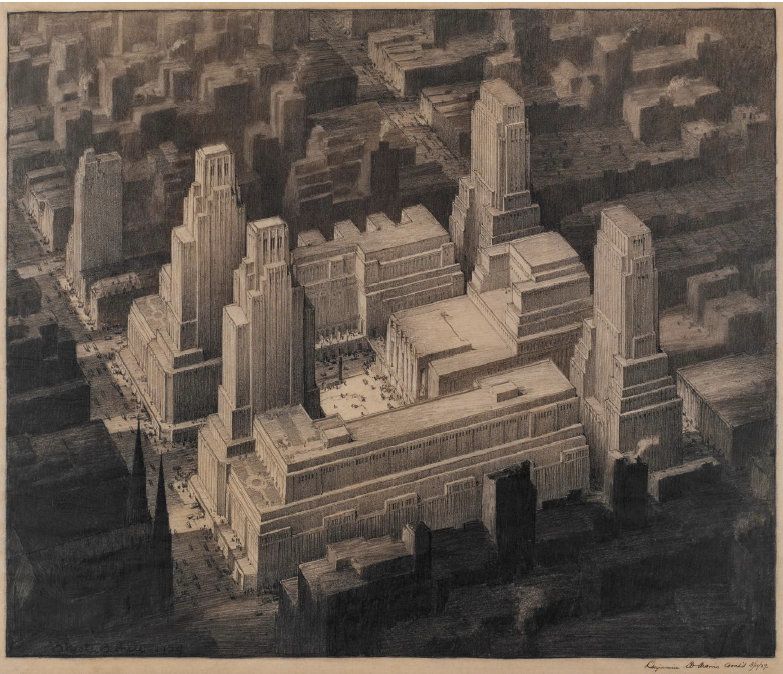

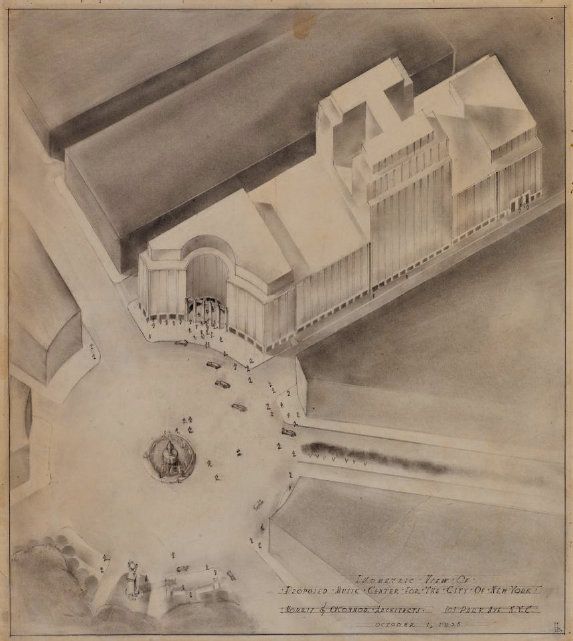

For almost half a century, unfulfilled plans to move the original opera house included the execution of architectural plans, fundraising, and surveys. Otto Kahn, the president of the Metropolitan Opera Company even bought land in 1925 between 8th and 9th avenues and 56th and 57th streets for the purpose of relocating the opera house there but his plans were rejected by the board of the opera.

In 1928, another proposal backed by John D. Rockefeller Jr. was put forth for the location that is now Rockefeller Center. The stock market crash of 1929 made financing unviable for the opera house and the Metropolitan Opera Company had to pull out of the project.

Columbus Circle came into play twice, once by Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia in the 1930s who wanted to build a municipal arts center there, and in the 1940s, Robert Moses supported the construction of the opera house at Columbus Circle, where he also wanted to build a convention center.

In the wings just off Founder’s Hall on the lower level of the Met Opera house there are two art galleries that are fairly unknown to most visitors. Currently, you can see the exhibit “The New Met: A West Side Story” that details the history of moving the Met Opera to Lincoln Center, with large reproductions of the never built plans on display along with many vintage photographs. The other gallery is exhibiting “Portraits from the Archives of the Metropolitan Opera” showing some of the Met’s greatest personalities in the form of paintings, sculptures, drawings and photographs.

The Metropolitan Opera normally stores five operas in the house at a time in its 16,400 square feet of storage. Offsite, a warehouse in 129th Street contains 300,000 cubic feet of storage. In the yard, there are 1500 containers each 40 feet long that have 4.3 million cubic feet of storage. An additional 104,000 cubic feet of costumes are stored in a climate-controlled storage facility.

Next, check out the Top 10 Secrets of Lincoln Center.

Subscribe to our newsletter