Last Chance to Catch NYC's Holiday Notalgia Train

We met the voices of the NYC subway on our nostalgia ride this weekend!

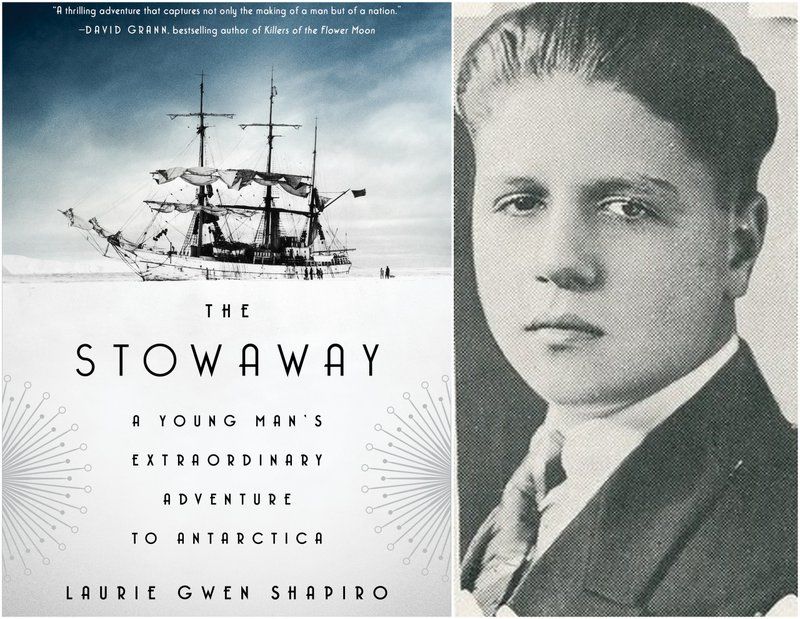

On January 16th, the highly anticipated book, The Stowaway: A Young Man’s Extraordinary Adventure to Antarctica will be released chronicling the doggedly persistent Billy Gawronski, a 17-year-old from New York City’s Lower East Side and his attempt to join Admiral Richard E. Byrd’s first expedition to the most southern continent. The book is written by Laurie Gwen Shapiro, a long time Untapped Cities writer, and published by Simon & Schuster.

The incredible true story is set in New York City, 1928 – before the stock market crash and in the last years of Prohibition. It’s a true American dream story, starring Gawronski who is a born and bred first generation New Yorker. As such, there are plenty of New York City locations, both still existing and since disappeared, to discover in this book. Continue on to see some highlighted locations.

Untapped Cities will also be hosting a book talk and party on January 19th (which is currently sold out) with Shapiro and science journalist, Corey S. Powell. If you didn’t get tickets, you can still get a copy on Amazon and email us at tours@untappedcities.com if you want to be put on the waitlist for the event!

Left, Billy Gawronski as a kid. He refused to take off his sailing suit after a trip to Europe. Photo from The Stowaway. Right, one of Billy’s childhood apartments at 233 East 9th Street. Photo courtesy of Laurie Gwen Shapiro.

William “Billy” Gawronski was born to Polish immigrants on September 10, 1910 in New York City. His father Rudy owned an interior decorating business and had lived at various addresses in today’s Lower East Side and East Village, the whole area commonly known as the “East Side” back in the day. After he was born, Billy first lived in a one-bedroom at 165 Avenue A at 12th Street, close to the St. Stanislaus Parish on East 7th Street, “the center of the Manhattan Polish community,” Shapiro writes. Rudy was active in the Polish National Home and even served as the President. In 1918, the family moved to a two-bedroom railroad flat at 233 East 9th Street, a building that still stands today (see photo above).

Billy went to school at PS 64 on East 6th Street and spoke English and Polish fluently, as well as Yiddish which he learned from his stickball friends on the Lower East Side. Billy would master five languages in his life, Shapiro writes. Billy was fascinated with stories of the era’s explorers, finding an idol in Admiral Richard E. Byrd, who had flown over the North Pole. Byrd’s future expedition to fly over the South Pole was a media sensation, a necessity cultivated by Byrd who needed to fundraise all private funds for the adventure. Billy, unsurprisingly, followed the story closely and desperately wanted to go.

Starting in 1924, Billy was enrolled at the Textile High School, a progressive new trade school in the New York City public school system at 343 West 18th Street in Chelsea, between 8th and 9th avenues. The Principal, William Henry Dooley, was a Harvard and Columbia University-educated educator, modeling his feeder school for the city’s garment industry after visiting the mill towns of Lowell, Massachusetts and garment trade schools in Europe. The Garment District was bustling back then, with plenty of work for potential graduates.

Billy majored in interior decoration, as his father intended for his son to attend college and then join him in the family business. The curious and bright teenager had average grades, but it was clear he was “suited more for gestalt experience than for traditional education,” Shapiro writes. Still, the diversity of the Textile High School certainly suited Billy. Several of his friends were black women who held leadership positions in the school.

Today, the building that housed the Textile High School, though the school, which had many different names over the years, is closed. It was most recently known as the Bayard Rustin Education Complex until 2011.

Get a copy of The Stowaway: A Young Man’s Extraordinary Adventure to Antarctica by author Laurie Gwen Shapiro on Amazon.

Billy Gawronski’s childhood home in Bayside, as seen today. Photo courtesy of Laurie Gwen Shapiro.

Rudy had long wanted more space for him and his family – even considering a return to Poland. In the end, he found what he was looking for in Bayside, Queens around the St. Josaphat Parish where a satellite Polish community was growing. The Gawronski’s moved to a single-family house at 4021 First Street at Ahles Road (the address today is 214-32 43rd Avenue. Shapiro describes this as “the farthest you could get from Manhattan without leaving Queens.” Billy commuted from Bayside to his high school in Chelsea every weekday on the Long Island Railroad.

Bayside during this time was a hot spot for America’s silent film stars, who were living in the upper class, posh portion of the neighborhood. Well-known actors like John Barrymore, Gloria Swanson, Maurice Costello and his daughter Dolores, Buster Keaton and James J. Corbett were living in Bayside, which was “secluded but a handy enough commute to Astoria, Queens, home of the Famous Players-Lasky Corporation (soon to be renamed Paramount Pictures) and the Kaufman studios, and also to Vitagraph Studios in South Greenfield Brooklyn (a neighborhood now called Midwood),” writes Shapiro.

Later in the book, Billy is excited to hear that Admiral Byrd is actually living in Bayside in 1928, renting the home of performer Andrew Mack. The location was not only more private, but it would get the explorer closer to where the planes he’d be flying over the South Pole were being serviced on Long Island near Roosevelt Field.

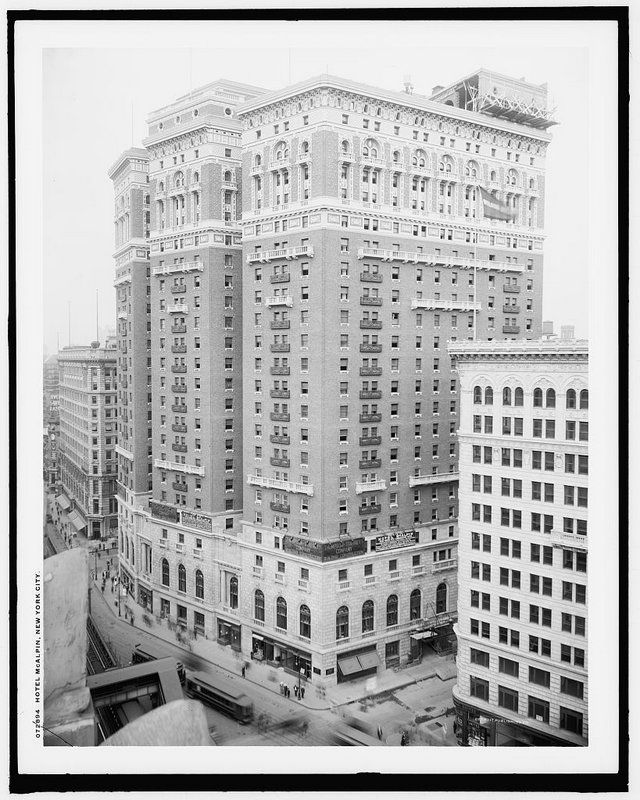

Image from Library of Congress

A “lackluster room” in the Hotel McAlpin at Herald Square was the first headquarters for Admiral Byrd’s Antarctica expedition. Shapiro also describes the one-room suite as “embarrassing,” at least to Byrd. The Hotel McAlpin was once the largest hotel in the world, completed in 1912. The building still exists, as a residential building on the corner of 34th Street and Broadway, but its famous restaurant, the Marine Grill, no longer exists.

New York City preservationists and history buffs will know, however, that details of the restaurant are actually located inside the Fulton Street subway station, including its well-known terra cotta murals by Fred Dana Marsh and a cast iron gate. You can see these remnants of the Hotel McAlpin on our popular Underground Tour of the NYC subway:

Underground Tour of the NYC Subway

Byrd would move the headquarters to the offices of publisher George “Gyp” Putnam, who was an explorer himself. The building at 2 West 54th Street was still considered by Byrd “not impressive enough for a commander,” so the headquarters would make yet another move.

Photo from Library of Congress, Detroit Publishing Co.

Byrd make a connection with John McEntee Bowman, the owner of the Biltmore Hotel, one of the hotels within the Terminal City complex at Grand Central Terminal, and arranged to have both his living quarters and the expedition headquarters relocated to the third floor of the hotel.

As Shapiro writes, “The Biltmore was a luxurious hotel next to Grand Central, significant enough to have played host to President Woodrow Wilson and Sherlock Holmes creator Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, and complete with its own private train track. Byrd knew his time there would coincide with that of former governor Al Smith, who was on another floor planning the Empire State Building. ..Byrd and Smith knew one another through friends and often asked asked each other’s highly publicized progress in the Biltmore’s elevators and lobby.”

Get a copy of The Stowaway: A Young Man’s Extraordinary Adventure to Antarctica by author Laurie Gwen Shapiro on Amazon.

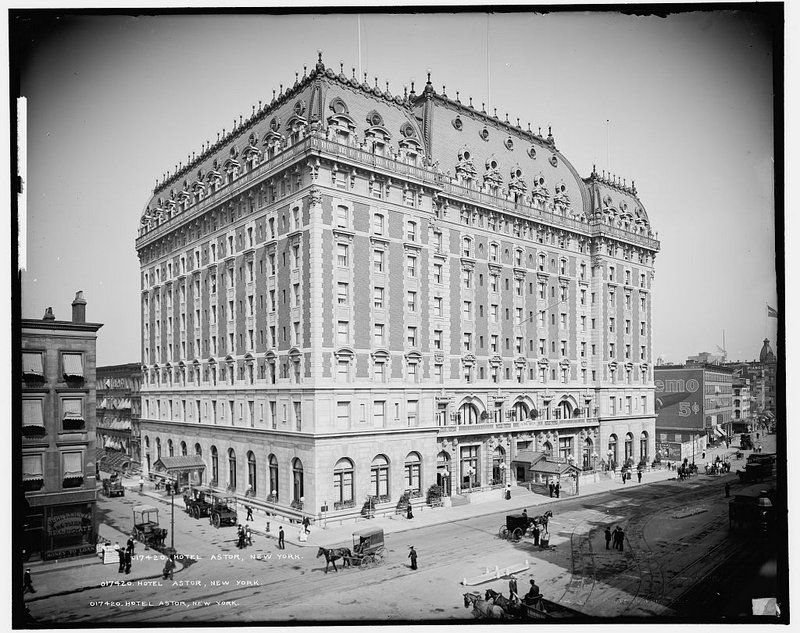

Old Waldorf-Astoria Hotel circa 1901. Photo by A. Loeffler from Library of Congress.

Old Waldorf-Astoria Hotel circa 1901. Photo by A. Loeffler from Library of Congress.

In the spring of 1928 Billy goes to senior prom with his first steady girlfriend in the old Waldorf-Astoria Hotel, which was located at 34th Street and 5th Avenue. Shapiro describes the scene:

Billy’s senior prom started Friday, May 4, at eight thirty, in the big dance hall at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel, with music by the Dick Stiles Orchestra. It was a relief to not enter the floor as a stag begging for a dance…that May night, the hall was bathed in fragrance, with flowers at every table and girls in evening gowns with flowers pinned in their hair gliding over the dance floor with their escorts, each, like Billy, wearing a boutonnière. The student newspaper the Textilian‘s final issue for the year called the evening perfect down to the last waltz.”

Not to be confused with the current Waldorf Astoria, the original hotel was demolished in 1928 and replaced by the Empire State Building. The hotel, the largest in the world when it opened in 1897, was built on the site of the Astor family mansion and designed by architect Henry Hardenbergh, who would later design The Dakota apartments.

The skybridge at Gimbel’s Brothers department store in Herald Square

Billy continued to chase down opportunities to join the Antarctic expedition. Two weeks before the first of Byrd’s four ships were to depart, Billy met one of the confirmed expedition members at a promotional event inside the Gimbel Brothers department store at Herald Square. The rival store to Macy’s was located at 33rd Street and Sixth Avenue and the event took place inside the music department.

Shapiro writes, “a seaman named Richard ‘Ukulele Dick’ Konter played his ukulele and talked about the expedition. He was learning Mammy songs, for the Maoris in New Zealand and the unknown native people they would perhaps meet in Antarctica….In his prior experience near the North Pole, he explained, classical music did nothing for ‘simpleminded natives’ – just jazz.”

Shapiro notes that such stereotypical songs and statements would be offensive today but were popular in the era. Konter would indeed perform “Alabama Mammy” in New Zealand during the expedition, and “of course, there would never be any indigenous peoples from him to meet” in Antarctica.

Gimbel’s department store still exists, though has long been converted into the Manhattan Mall. A beautiful skybridge still exists between the main building and its annex – you can peek inside it in a previous Untapped Cities article.

The City of New York boat, anchored in Antarctica. Photo from the German National Archive via Wikimedia Commons.

Byrd’s ship, the City of New York, arrived to New York harbor with much fanfare. It was an old-fashioned multi-masted wooden ship that weighed 200 tons and spanned half a city block. The ship, had “seen duty as an Arctic icebreaker for Norwegian seal hunters starting in 1885. On one run in icy waters in 1912, her captain had been the last to see the Titanic.”

The City of New York would be the first of Byrd’s flotilla to leave for Antarctica. Two-thousand people would eagerly go on board in a public “open house” of the boat at Hoboken‘s Pier 1 just nine days before the ship sailed. Captain Frederick Melville, second cousin of writer Herman Melville, welcomed the visitors, many who had come, like Billy, to Hoboken via the 14th Street Ferry. The entrance fee was $1, which went into the expedition coffers.

Billy took it as an opportunity to scout out where he might be able to stow away, once he got to the City of New York after swimming across the Hudson River on the evening of August 24th, 1928. He would get an unexpected surprise once he got to his hiding spot.

Get a copy of The Stowaway: A Young Man’s Extraordinary Adventure to Antarctica by author Laurie Gwen Shapiro on Amazon.

Billy aboard the Eleanor Bolling. He is in the black shirt on the front right. Photo courtesy Simon & Schuster.

Billy won’t make it to Antarctica on the City of New York, after getting caught but undeterred, he makes for the Chelsea, which is due to leave on September 16th from the Tebo Yacht Basin in Gowanus, at Third Avenue and 23rd Street. The basin is owned and operated by William Todd, and was “the spot for the yachts of the Atlantic seaboard’s most aristocratic and prosperous residents,” Shapiro contends, including the boats of Cornelius Vanderbilt and J.P. Morgan. Todd was a great friend of Byrd’s and allowed the explorer to dock the Chelsea at the Tebo Yacht Basin.

The Chelsea itself was an 800-ton iron freighter originally built as the HMS Kilmarnock for the British Royal Navy during WWI. Byrd renamed this boat, like he did the City of New York, as the Eleanor Bolling for his mother (though the painter would forget an “l” on Bolling” and a redo was deemed too expensive. Billy would be caught three times on the Eleanor Bolling, and thrown off.

During a furlough back from Antarctica in 1929 (more details about that in the book), Billy would go to the Paramount Building in Times Square with his family to see a model of Little America, the village Byrd’s team built on Antarctica to winter over before the flight over the South Pole. The model was part of the promotion for the Paramount documentary about Byrd’s expedition, With Byrd at the South Pole. Billy’s presence at this event was exciting for other attendees who called out to others, “Come meet the stowaway!”.

The Paramount Building still exists today as an office building and home to the Hard Rock Cafe.

11. The Rialto Theatre

Photo from Library of Congress.

The documentary With Byrd at the South Pole would actually open in 1930 at the Rialto Theatre in Times Square on the corner of 42nd Street. The film would win an Academy Ward for Best Cinematography, the only documentary to win this award to date. Billy is seen in the documentary building an igloo and unloading supplies.

The theater was demolished in 2002 and a high-rise building sits in its place now (where ESPN Zone is located).

Get a copy of The Stowaway: A Young Man’s Extraordinary Adventure to Antarctica by author Laurie Gwen Shapiro on Amazon.

Pier A, newly restored, hosted 5,000 excited onlookers from all over the country who wanted to greet Admiral Byrd on his return from Antarctica.

We’ll leave you to discover in the book The Stowaway exactly how Billy actually gets to Antarctica after so many setbacks. When Byrd returns to New York on June 19th, 1930, the two main ships, the Eleanor Bolling and the City of New York arrived together into New York Harbor for maximum photographic effect.

The ships were cleared at the Scotland Lightship Quarantine Station in the Ambrose Channel off Sandy Hook (faster than going through Ellis Island) and were greeted by more than five thousand excited onlookers at Battery Park’s Pier A, a half million people elsewhere onshore, and a military flotilla. “A thirteen-gun salute sounded from Governors Island,” writes Shapiro, Ships on the Hudson echoed in whistle salute. The enormous navy dirigible Los Angeles and two smaller British airships passed overhead.” The boats would dock further uptown, charging admission for entry.

Photo courtesy Laurie Gwen Shapiro

Byrd is also given a tickertape parade on the day of his return in what was known as the Canyon of Heroes from the Battery to City Hall. It’s called a tickertape parade because actual Wall Street ticker tape would rain down, along with “torn telephone directories, and adding-machine tape thrown through windows above,” writes Shapiro. BIlly would get to ride in one of the cars of honor in this parade.

Other explorers to have ticker tape parades include Amelia Earhart and Charles Lindbergh but Byrd is the only man known to have had three parades in his honor.

One of the several former locations of the Seaman’s Church Institute at 241 Water Street. The original location, where Billy would have gone to was at 25 State Street (since demolished). You can see a photo of it in the book Anchored Within the Vail: A Pictoral History of the Seamen’s Church Institute

The Seaman’s Church Institute of New York plays a recurrent role in the story of Billy Gawronski and the Antarctic expedition. The Institute is a direct descendent of the floating churches that once dotted the New York City waterfront, providing much needed services to visiting sailors, like housing, mail delivery, religious services, and temperance societies. The New York Times reported that in 1931 that 8,000 to 12,000 sailors visited the Seaman’s Institute daily, such was its importance! One of the institution’s main buildings was at 25 South Street.

George Tennant, the chief cook of the expedition had “lived since his youth on South Street” in the Seaman’s Church Institute. In the celebration after the group’s return to New York City, fifteen out of town sailors who did not have families in New York City or funds were hosted at one of the two Seaman’s Church hotels, paying $0.75 a day. Captain Gustav Brown, who commanded the Eleanor Bolling, continue to live in the Seaman’s Institute, after the celebrations was over, looking for his next job.

And in the fall of 1932, many of the expedition members happened to converge on the Seaman’s Church Institute for Thanksgiving, partaking in the Soldiers and Sailor Club’s free Thanksgiving meal, including Billy, Harry King (a second mate on the Eleanor Bolling), Arthur ‘Hump’ Creagh, John Cody (the Bolling’s first engineer), Kess from the Bolling’s stokehold, and Isaac Erickson. The impromptu reunion was reported in the Associated Press.

Finally, in 1958, Billy would take his second wife, Gizela, from Poland to the Seaman’s Institute to show her “how the men there had helped him ride out the roughest days of the Depression, and about the day he unexpectedly ate Thanksgiving dinner with so many of his old friends,” writes Shapiro.

The Seaman’s Church Institute still has a location downtown and a far more recent location at Newark Airport. The location may be unexpected, but given the move of the port to New Jersey, it’s a much more practical location. Take a special look inside this church in our previous Untapped Cities article. There are also Norwegian and the Swedish seaman churches still located in Manhattan.

Get a copy of The Stowaway: A Young Man’s Extraordinary Adventure to Antarctica by author Laurie Gwen Shapiro on Amazon.

Hotel Astor. Photo from Library of Congress.

On the evening of the parade, Billy attended a formal dinner at the Hotel Astor in Times Square. As Shapiro writes, it was an even larger bash than the luncheon held for Admiral Byrd at the Advertising Club of New York, “broadcast live by radio stations WOR, WABC, and WNBC. In a dinner coat borrowed from his father, Billy took his place–mercifully, Byrd’s expedition heroes were grouped together–at table A, seat 5. The lavish menu was a bounty of food the likes which had not been in the iciest of continents, and would have been scandalous to serve even a year later as the economy fared ever worse.” The French-influenced menu is reproduced in full in the book.

The elaborate Hotel Astor, with a rooftop pleasure garden, and ornate architecture (across many styles), was demolished in 1972, one of the many lost hotels on Broadway. The site is now home to MTV Studios and other businesses.

Photo courtesy Simon & Schuster.

Another reception took place at the Hotel St. George in Brooklyn Heights. A photo of the event, showing men in tuxes seated around numerous round dinner tables, amidst many celebratory flags and bunting, hung in Billy’s living room in later years.

The once-grand Hotel St. George still stands but is very altered, having once served as housing for the homeless and AIDS patients, and suffering a massive fire in 1995. Today, part of the hotel is now dormitory housing. The original lobby has become the entrance to the Clark Street subway station. A fun visit is to find the remnants of the original hotel that are still visible.

Before Billy set off for Antarctica, he was accepted into both City College and Cooper Union. His father Rudy was eager for him to study at Cooper Union, not just for the free tuition but so Billy could continue his design education and join him in his interior decorating business. However, Billy was not able to matriculate as school started while he was on his Antarctica adventure.

When he returned, Billy’s days were filled with social engagements honoring the men of the expedition but paying work was hard to find in the heart of the Great Depression. Billy worked for a time as an assistant lecturer on the railroad. During this time, Admiral Byrd offered Billy help should he need anything. Billy decided, when the lecturing gig ended, he would apply to Columbia University to prepare him for a future life as an explorer.

Billy asked Admiral Byrd for a recommendation letter, which he wrote directly to Columbia University President Nicholas Murray Butler (for whom the library at the university is named for). Billy would not only be accepted on extremely short notice (he applied within a few days of school starting), but he also received a partial scholarship.

Admiral Byrd would give two lectures about the South Pole expedition at Columbia in the fall of 1930 and both times, he called up Billy to the stage.

Get a copy of The Stowaway: A Young Man’s Extraordinary Adventure to Antarctica by author Laurie Gwen Shapiro on Amazon.

Subscribe to our newsletter