Last Chance to Catch NYC's Holiday Notalgia Train

We met the voices of the NYC subway on our nostalgia ride this weekend!

Welcome back to our regular column on “Must Visit Places” in NYC’s neighborhoods, written by one of our contributors who are residents of that neighborhood. This week’s guide is by Untapped New York tour guide Alan Cohen.

“Upstate” Manhattan has a decided residential feel, and it also contains many gems for any lover of things New York. You have to come here to really know our beloved city. If you’d like to visit the oldest house in Manhattan, see the best views in any park in the City, enjoy great food and drinks, all for one subway fare, then you must visit the Heights, even more recently made famous by the release of the Lin Manuel-Miranda film In the Heights.

Washington Heights is generally held to run from 155th Street on the south to Dyckman Street on the north and from the East River to the Hudson. The neighborhood includes Hudson Heights (north of 181st Street and west of Broadway) and Fort George (north of 181st Street and east of Broadway). Historically, the high rocky ridge that dominates the western part of northern Manhattan played a role in the American Revolution (the site of Fort Washington) as well as becoming a desired location for Gilded Age estates with magnificent Hudson River views.

With the development first of rapid mass transit at the start of the 20th century (IRT line, now the 1) and then the addition of the IND (A and C lines) in the early 1930s the area expanded quickly. With an easy commute to jobs downtown and an abundant stock of low-rise, predominantly Art Deco apartment buildings, living in the Heights became a residential step up from tenement housing in lower Manhattan.

While numerous ethnic groups had lived side by side in the Heights, some populations, like the Greeks, have largely relocated, while others, like Jews and Irish, have remained. By the 1960s, Dominicans became the predominant ethnic group, bringing a different flavor to the shopping and restaurants as well as the sounds of Spanish language and music to the streets. While Dominicans are still the dominant group in the Heights, immigrants from other Latin American countries have added to the diversity.

Between the 1980s and early 1990s, parts of the Heights had become home to the crack epidemic and the violence that accompanied it. Working with local police, determined individuals and diverse community groups united to fight the scourge, and crime dropped. Today the area is one of the safest in Manhattan. With low crime, relatively affordable spacious apartments, an abundance of parks, and an easy commute to midtown, the Heights has seen real estate prices soaring and people coming just for the day or to explore some of the must-see sights. And, oh, it hasn’t hurt that Lin-Manuel Miranda has celebrated the neighborhood in his hit musical and film, In the Heights, to become a Hollywood film produced by Jay-Z.

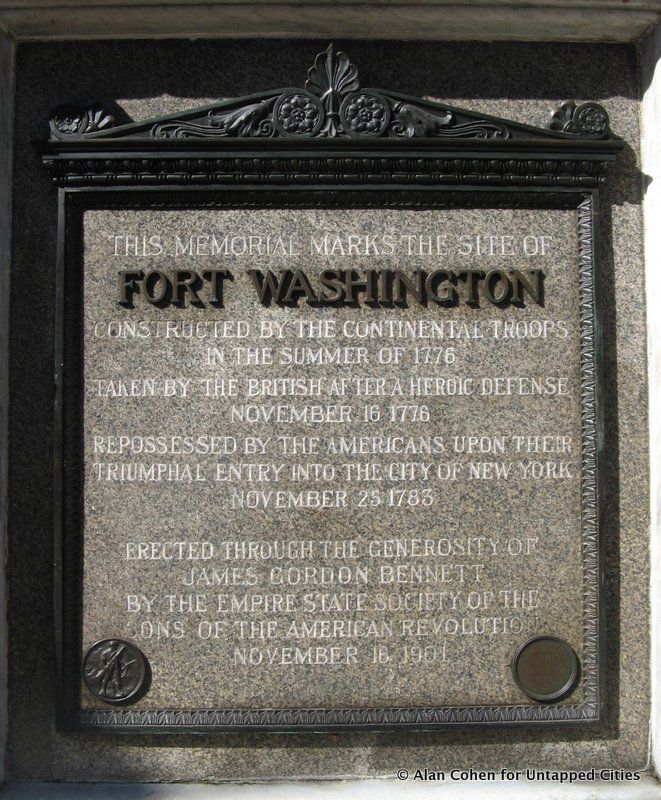

The highest natural point on Manhattan is found in Bennett Park located at about 183rd Street and Pinehurst Avenue. There’s an official plaque set into the rock, marking it as 265.05 feet above sea level. Bennett Park was the site of Fort Washington, the last stronghold in Manhattan of General Washington’s army and a resounding defeat by the Hessian and British onslaught. There is a replica of a Revolutionary War cannon, playground equipment, and a comfort station.

The Heights has two must-have historic sites if you want to see places largely intact.

Children’s literature matters! The Little Red Lighthouse is the only lighthouse remaining on Manhattan island, albeit a non-functioning one, is the subject of the 1942 beloved children’s book The Little Red Lighthouse and the Great Gray Bridge, written by Hildegarde Swift and illustrated by Lynd Ward. The lighthouse, originally located at Sandy Hook, New Jersey, was placed on a spit of land named Jeffrey’s Hook, a navigation hazard throughout much of our early history.

A variety of warning devices were used over time in this spot, culminating in the 1921 installation of this 40-ft. tall cast iron light and fog bell. By 1931 the lights of the newly erected George Washington Bridge directly overhead illuminated the river beneath and rendered the lighthouse obsolete. Decommissioned in 1947, the lighthouse was scheduled to be sold for scrap in 1951. The well-known story of the friendship between the little round lighthouse and the mighty gray bridge galvanized children and their parents to advocate, successfully, for the preservation of the structure. Now, an annual festival is held in September to include a book reading and tour. The lighthouse has also been opened for visits during Open House New York in the fall and through NYC Park Ranger events. Even if you don’t get to go in, walking or biking past it is a visual treat.

To visit: Take the A train or a bus (M98 or M4) to 181st Street. Walk west to Plaza Lafayette. Cross the footbridge and take a left down the path under the overpass. Cross over the railroad tracks and follow the path to the left (south). The lighthouse is almost directly under the George Washington Bridge.

New Yorkers love to boast that our free tap water is great stuff, better than bottled water. While the first settlers in New Amsterdam may have enjoyed healthy, delicious local water from ponds, wells, and springs, the city’s population outgrew and polluted its local water supply. By 1835 we were short on water to fight fires, and local water was generally foul. If you could afford it, you bought bottled water or had it carted in from “sweet” wells.

City planners understood the dire situation and commissioned a major feat of engineering: the construction of a 41-mile long, gravity-fed system bringing ample, healthful water into Manhattan. This monumental task entailed damming the Croton River in Westchester County and constructing a series of conduits, ventilation towers, a receiving reservoir (where the Great Lawn is now in Central Park), and a distributing reservoir (now the site of the New York Public Library on Fifth Avenue and 42nd Street).

To cross the Harlem River, the High Bridge was constructed to carry the metal water pipe into Manhattan. The Croton Aqueduct system was constructed between 1837 and 1842 when it opened with a major celebration. The stone, Roman-like aqueduct went into use in 1848, replacing a temporary system across the river. The walkway over the High Bridge was added later and opened only to foot traffic in 1864. The Water Tower, a Romanesque Revival structure that looks like it needs a castle to guard, was added in 1872 to pump water up to the top of the hill were a reservoir was constructed (replaced by the High Bridge Park public swimming pool).

The original Croton Aqueduct became obsolete as our need for water in the ever-expanding city demanded more than this system could provide. The bridge was deteriorating during the 1960s, then entirely closed from the cash-strapped 1970s on and essentially allowed to decay. Community action with eventual support from various mayors and over $100 million from public and private sources enabled the rehabilitation of the High Bridge, which opened for bicycles and pedestrians again in 2015.

To Visit:

From the Manhattan side, enter Highbridge Park at West 172nd Street and Amsterdam Avenue, then walk east to the High Bridge Water Tower Terrace staircase and down to the bridge level. From the Bronx side, enter at University Avenue and 170th Street in Highbridge.

For ADA access, use the ramp at 167th Street and Edgecombe Avenue on the Manhattan side or the ramp north of 170th Street and University Avenue on the Bronx side.

As you stroll the Heights and find yourself in need of a delicious treat, you will encounter bakeries and street vendors offering such savory treats as chicken (pollo), cheese (queso), or ground meat (res) empanadas as well as sweet pastries (dulces) and cakes (postres). Don’t be surprised to see the Jewish treat, rugelach, for sale in a Dominican bakery. If you want to sit down to savor your latte or do some work on a laptop while sipping your café con leche, check out the locally owned mom-and-pop stores like these two local favorites:

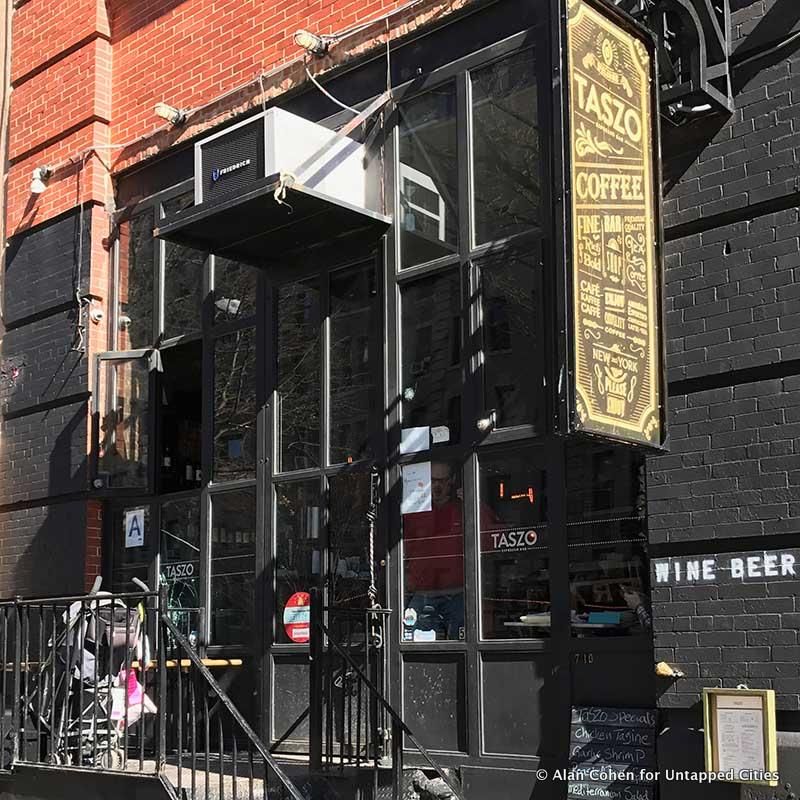

Located at the southern end of the Heights, at 5 Edward Morgan Place (b/t 157th and 158th Streets), Taszo has a designated area for people to work on their computers and a variety of foods including eggs Benedict and smoked salmon on a bagel to accompany their array of coffees. Taszo also offers wine and beer.

If you are going to Fort Tryon Park and want lunch or a snack, there is a strip of shops on 187th Street, between Fort Washington Avenue and Cabrini Boulevard. Frank’s Gourmet Market is a good place for a made-to-order sandwich or even prepackaged sushi.

For another indie coffee shop try:

Located at 213 Pinehurst Ave (close to where Pinehurst intersects Cabrini), Café Buunni offers light meals, such as panini, locally sourced sweet and savory baked goods, and hand-made trinkets from the owners’ native Ethiopia. Café Buunni has been planning to co-locate in the nearby George Washington Bus Terminal Market into a much larger space, but this major construction project has gone years and many millions of dollars above budget. Work at the mercado seems to be moving along, but for now, visit Café Buunni in its current and sole location, a former shoe repair shop.

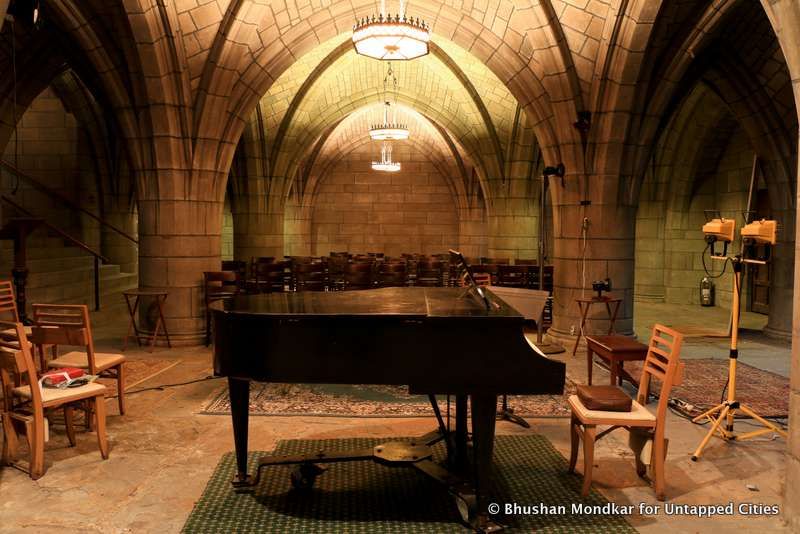

The Trinity Church Cemetery and Mausoleum and the Church of the Intercession form the southern border of Washington Heights. The non-denominational cemetery is the only active one in Manhattan, the resting place of John James Audubon, whose estate this originally was; Clement Clarke Moore (A Visit From Saint Nicholas); actor Jerry Orbach; Mayor Ed Koch; and other notables. The cemetery runs from 153rd to 155th Streets and from Riverside Drive on the west to Amsterdam Avenue on the east. The Church of the Intercession hosts a great series of jazz concerts in its crypt.

Between West 155th and 156th Streets on Broadway you’ll find the entrance to the Audubon Terrace Historic complex. Beaux-Arts buildings surround a central plaza decorated with sculptures by Anna Hyatt Huntington. Currently home to the bilingual Boricua College, the complex also houses the Hispanic Society of America. The latter, with its collection of important Hispanic art is well worth a visit, but is undergoing extensive restoration and will be closed until some time in 2019. The Academy of Arts and Letters is open to the public however, and contains the Connecticut studio of musician Charles Ives recreated piece by piece.

The Swallow-tailed Kite located at 575 West 155th Street

The Swallow-tailed Kite located at 575 West 155th Street

Across Broadway, facing the Audubon Terrace complex, beyond a gas station, is a nondescript apartment house that has its Broadway façade painted top to bottom with birds Swallow-tailed Kite (and others), by Lunar New Year. This lucky gas station, on its north end, has another mural, Fish Crow, by Hitnes. The murals are part of the Audubon Murals project co-sponsored by the Audubon Society and a local art gallery to promote awareness of bird species nearing extinction.

The ongoing project asks artists to paint one or more endangered birds on the sides of cooperating buildings or storefront security gates. Most of these paintings are in the adjoining neighborhood of Hamilton Heights, but another great one can found be close to the Morris-Jumel Mansion on West 163rd Street between Amsterdam and Edgecombe Avenues—Tri-Colored Heron by Iena Cruz.

Farther north on Broadway, between West 165th and 166th Streets is a remnant of the former Audubon Ballroom. Originally constructed in 1912 by Hungarian immigrant William Fox, creator of 20th Century Fox, the Audubon consisted of a 2,500-seat theater and a ballroom for 200 guests on the second floor. The theater first functioned as a vaudeville house where the likes of Lucille Ball, Desi Arnaz, Henny Youngman, the Three Stooges, and Mae West performed. Later the space was used as a movie theater, and eventually as a key meeting place for political activism. In the 1930s, the Emes Wozedek Jewish congregation began using the rooms in the basement for religious practices. Several unions also used the building for meetings, including the Municipal Transit Workers, the IRT Brotherhood Union, and the TWU (remember Mike Quill who greeted Mayor Lindsay with a transit strike?).

The Audubon Ballroom became an important landmark for the African-American community in Harlem and Washington Heights in the 1950s. The annual New York Mardi Gras festival, where the King and Queen of Harlem were crowned, was held here. When Malcolm X returned from his pilgrimage to Mecca in 1964, he formed the Organization of Afro-American Unity that met weekly in the ballroom. On February 21, 1965, Malcolm X was shot to death on the 2nd-floor stage while delivering a speech.

Statue of Malcolm X inside Audubon Ballroom

Occupying the full block, the building, notable for its ornate terra cotta ornamentation, was not kept up over the years. The nearby Columbia-Presbyterian Hospital sought to purchase the site and raze the building. A battle ensued between preservationists, who wanted to honor the rich history of the site as well as its architectural features, and those who saw greater value to the community in a new proposed research facility. The eventual compromise is an example of adaptive re-use in which much of the ornate façade was kept, a smaller research facility was built, and the lobby and second floor ballroom were repurposed as an educational center.

Today there is no sign commemorating the ballroom. The address, 3940 Broadway, just seems home to a ground-floor restaurant and office space, but once in the lobby you see a statue of Malcolm X on a platform and realize you are in a special place. The Malcolm X and Dr. Betty Shabazz Center is open weekdays from 11 a.m. to 6 p.m. The second floor, where Malcolm X was killed, has murals and quotes honoring the civil rights leader.

The United Palace opened in 1930 as one of the metropolitan area’s five Wonder Theatres, flagship entertainment palaces built by the Loew’s corporation. Originally called the Loew’s 175th Street Theatre, the ornate interior is a mash up of different architectural styles from Egyptian to art deco; if you can name a decorative motif you can probably find it here. The first show included a film starring Norma Shearer and a live vaudeville review probably accompanied by the theatre’s pipe organ. The last film to be shown here as a Loew’s theatre, in 1969, was 2002: A Space Odyssey.

As the era of single-screen large movie houses came to a close, several of these Wonder Theatres were purchased by religious organizations. The Reverend Ike (Frederick J. Eikerenkoetter II) obtained the building, renamed it the United Palace, and began to use it as a non-denominational center for “universal spirituality and creative expression.” The Reverend Ike, and later his son, Xavier Eikerenkoetter, maintained the building and added a community cultural center, United Palace of Cultural Arts (UPCA).

The UPCA has hosted dance performances, including the seasonal Hip Hop Nutcracker; film showings, some hosted by Lin-Manuel Miranda; and an “I’ll have what she’s having” showing of When Harry Met Sally with a deli dinner for couples. Now with its the newly restored pipe organ the UPCA has had silent film showings. It may not be worth a special trip just to see the terracotta exterior of the building, but jump at any chance to take in the gorgeous interior and their fun cultural offerings.

Several streets surrounding the Morris-Jumel Mansion comprise a lovely historic district including the block-long Sylvan Terrace. This stone-paved street was originally a private carriage drive connecting the mansion to Saint Nicholas Avenue, an historic thoroughfare between Manhattan Island and the mainland (the Bronx). The double row of 20 wooden houses was built in 1882 and restored in 1980. Approaching Sylvan Terrace up the stairs from Saint Nicholas Avenue between West 160th and 161st Streets, you’ll see the Morris-Jumel Mansion at the end of the block and you might just think you’ve travelled back in time to some quaint village.

While it may seem odd to name a one-block-long street an avenue, its short length (running from West 186th Street to West 187th Street one block west of Cabrini Boulevard) is more than made up for by its magnificent view of the Hudson River, the bridge, and the New Jersey Palisades. Named after Lucius Chittenden, an early 19th-century landowner, the avenue has houses only on the eastern side of the street, leaving an unobstructed view to the west. To further add to the lure of Chittenden is the so-called pumpkin house at #16. This structure is cantilevered over the Henry Hudson Parkway below and affords residents views of the George Washington Bridge, the Palisades to the west, and all the way north to the Tappan Zee Bridge. It’s known as the pumpkin house because when they’re lit at night its western windows resemble a carved jack-o’-lantern.

Washington Heights is home to numerous satisfying Latin American restaurants. While it will be easy to find familiar foods like pork cutlets or rice and beans almost anywhere, there are some less familiar offerings, such as pupusas (Salvadorean gluten-free cornmeal patties stuffed with various fillings). To learn a few of the many ways plantains can be prepared, you must visit Malecon or another Dominican restaurant with mofongo in its name. Ripe plantains can be offered as maduros, sweet side dishes or in an omelet. Unripe green plaintains may be prepared as tostones, a savory food usually enhanced with a hint of salt; cut-up plantain is fried twice, first to soften and then flatten the slices and second to brown the slices. While tostones are a great side, a main dish called mofongo uses the green plantain as its base. Chicken, beef, seafood, bits of fried pork skin, alone or in combination, usually topped with gravy are added to the mashed plantains resulting in one very filling, tasty meal.

Northern Manhattan is blessed with an abundance of parks. In Washington Heights we have the Highbridge Park on the east, the Hudson River Greenway, J. Hood Wright Park, several smaller green spaces, and the must-see Fort Tryon Park.

Built on land that was once home to several estates, all with sweeping views of the Hudson River and New Jersey Palisades, Fort Tryon Park and the Cloisters may be the best gifts New York City ever received. John D. Rockefeller Jr. (aka Junior) bought the land, paid for the construction of the park, acquired the art and artifacts for the Cloisters and then gave it all to the citizens of the city. Junior hired Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. to design the park, so it should be no surprise to those familiar with Central Park, designed by Olmsted Sr., to find a similar design aesthetic with curving paths, rustic stonework, and curated views.

Favored by locals for dog-walking, sledding in the winter, yoga in the morning, or just a stroll, the park is home to the Heather Garden. With its specimen trees, annuals, and perennials offering texture and color, the Heather Garden is the largest accessible garden in the city (no fee to enter, open whenever the park is open). While the garden plants are breathtaking from spring to fall, many heaths and heathers have color all year, including the depths of winter, a welcome visual pick-me-up for anyone walking through the park.

To Visit Fort Tryon Park, the New Leaf Café, and the Cloisters:

Bus: The M4 and M98 (rush hours only) travel to the park.

Subway: A train to 190th Street station, take the elevator to Fort Washington Avenue and turn right at the top of the stairs. Follow the signs to the café or museum once in the park; the Heather Garden is directly ahead.

The Morris Jumel Mansion, the oldest house in Manhattan, was built in 1765 as a summer retreat for Colonel Roger Morris and his wife, Mary Phillipse. The colonel, who fought with George Washington during the French and Indian Wars, fled New York when the American Revolution was imminent because as a Tory he favored the British cause. After the 1776 British invasion of New York City, the house became General Washington’s headquarters for about five weeks. From the home’s high perch on a hilltop, with clear views in all directions, Washington could direct the Battle of Harlem Heights, an early American victory, albeit temporary. After the American defeat at nearby Fort Washington, the mansion was home to British officers and their Hessian allies.

In 1810, French merchant Stephen Jumel purchased the mansion and with his American-born wife, Eliza (earlier his mistress), decorated the house to suit their style. While he traveled extensively for business, she remained at home securing and growing the family fortune and amassing what was for its day a prominent art collection. Eliza, clearly a self-made woman, became one of New York’s wealthier citizens, but her past, including a mother who had prostituted herself to survive, always seemed to cast a shadow on Eliza’s status as a prominent citizen.

After Stephen died in 1832, Eliza wed former Vice President Aaron Burr in the front parlor. It was a short-lived marriage of convenience: money was likely Burr’s motivation, and Eliza wanted the cachet of being the wife of the (former) vice president. Eliza lived in the house until her death in 1865. There ensued a bitter and long fight between potential heirs of the Jumel fortune. The property, once river to river, was divided into saleable lots and household treasures were sold off. Miraculously the house survived and was ultimately bought by the city in 1904 to become a museum.

Mansion visitors can tour on their own or with a docent to learn about daily life here as well as the fascinating stories of its many residents — with at least one good ghost story. Alexander Hamilton visited the mansion in the early days of independence (as did Thomas Jefferson and John Adams). Ironically, one of Hamilton’s sons, also an attorney, served Aaron Burr with divorce papers here.

Please consult the Morris-Jumel Mansion’s website for hours, travel directions, and tour information.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s northern branch, the Cloisters, specializes in the art and architecture of the Middle Ages. The museum is another gift of John D. Rockefeller Jr., an exceptional philanthropist but not especially a fan of religious medieval art. Knowing that the art was important, Junior realized it needed to be preserved and made available to the public. He understood that a perfect setting would be within another of his gifts to the city — Fort Tryon Park.

Working with art advisors, Rockefeller purchased the Unicorn Tapestries and hundreds of other decorative objects and remnants of European abbeys and a cloister. Much of the purchased collection came from an American sculptor cum art dealer, George Grey Barnard, who amassed the bulk of what would become the Met Cloisters. Barnard displayed his finds in his own Cloisters museum just a few blocks south of the park.

Using arches, remnants of columns, and fragments of ruins from five different buildings from different periods of time, Junior’s architect, Charles Collens, was able to construct the once-separate structures into a unified building. As you walk from section to section, often around a central garden with fountain, you’ll find the architecture and views are greatly to be admired. If you like religious art, such as intricately carved boxwood rosary beads (imagine a 3-D hillside crucifixion scene carved into a golf ball–sized bead), then you will be overjoyed. For others, the serenity and beauty of the architecture can be moving. The Cloisters is a wonderful place to remember people, like Junior, who devoted their lives to preserving our natural and cultural history, taking pleasure in giving away money rather than in amassing more.

Visitors should know that the Met requests a $25 donation to enter, but the official policy is to pay what you wish. If you combine a visit to the Met on Fifth Avenue or the Met Breuer with the Cloisters, admission is free for the day (hold on to your receipt and tag).

Built with a single deck (opening in 1931), a lower deck was added in 1962, making the George Washington Bridge the world’s only 14-lane suspension bridge. With over 105 million vehicles crossing per year, it is the busiest motor vehicle bridge in the world. While notorious for traffic jams either on the New Jersey side in Fort Lee or on the New York side, the George Washington Bridge is simply beautiful, though it was not originally intended to showcase its steel structure. The bridge’s principal designer, Swiss-born engineer and architect Othmar Ammann, has a notable legacy in New York City including the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge, the Bronx-Whitestone Bridge, Lincoln Tunnel, and Triborough Bridge (now Robert F. Kennedy Bridge).

Views of the bridge’s towers grace the Heights. If you drive along the Henry Hudson Parkway, walk or bike along the Hudson River Greenway, or stroll through Fort Tryon Park, you can see nearly the entire span and towers. An especial visual treat when illuminated at night, the George Washington Bridge also sports the world’s largest free-flying American flag ten days a year, including Martin Luther King Jr. Day and Independence Day.

Locals travel downtown or to the Bronx for large department stores, big-box stores, specialty grocers like Trader Joe’s, or most national chains. Primarily a residential community, the Heights is home to mom-and-pop shops and service providers. You’ll also find some shops that are unique to Hispanic neighborhoods, like botanicas featuring religious goods, candles, herbs, and perhaps occult items.

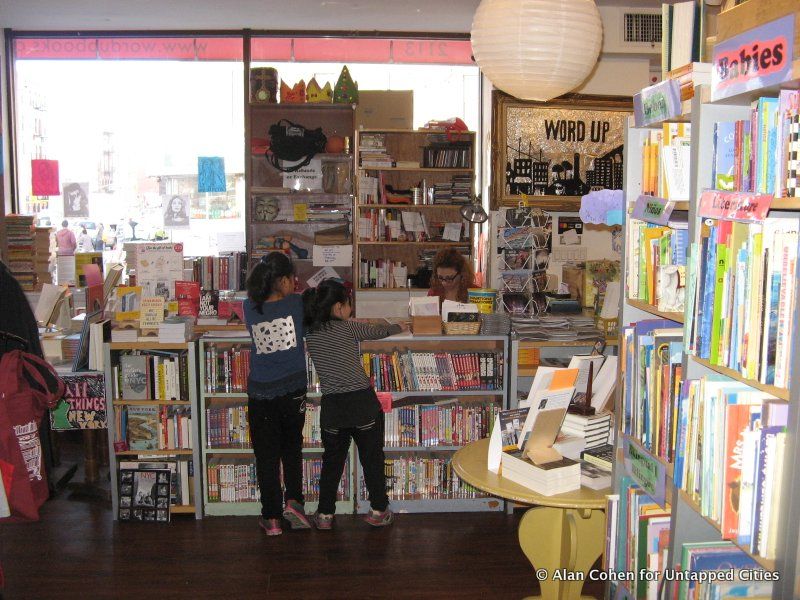

One area favorite destination is Word Up, a multilingual community bookstore, arts space, and support center for social activism in a volunteer-run warm and welcoming environment. Located at 2113 Amsterdam Avenue at 165th Street, you might like to combine a visit here with a trip to the nearby Morris-Jumel Mansion. The hours of this Liberia Comunitaria are Tuesday through Friday 3 to 9 p.m., Saturday 11 a.m. to 6 p.m., and Sunday noon to 6 p.m. They sell new and gently used books and have a membership Community Supported Bookstore (CSB) program. Similar to a CSA, or community supported agriculture, at Word Up your dollars support the bookshop and you receive books rather than veggies.

Next, check out our neighborhood guides to Crown Heights and Astoria.

Subscribe to our newsletter