NYC’s Forgotten ‘War on Christmas Trees’

Discover how an obscure holiday crackdown affects festive street vendors today!

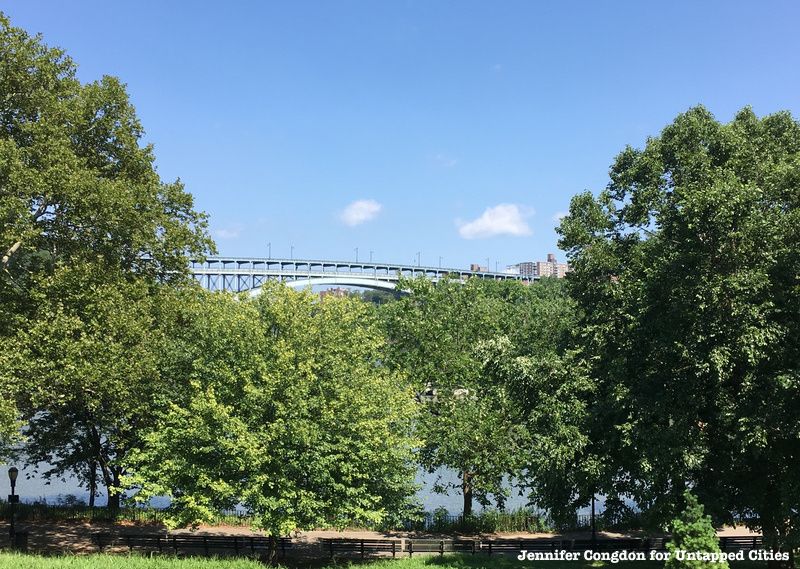

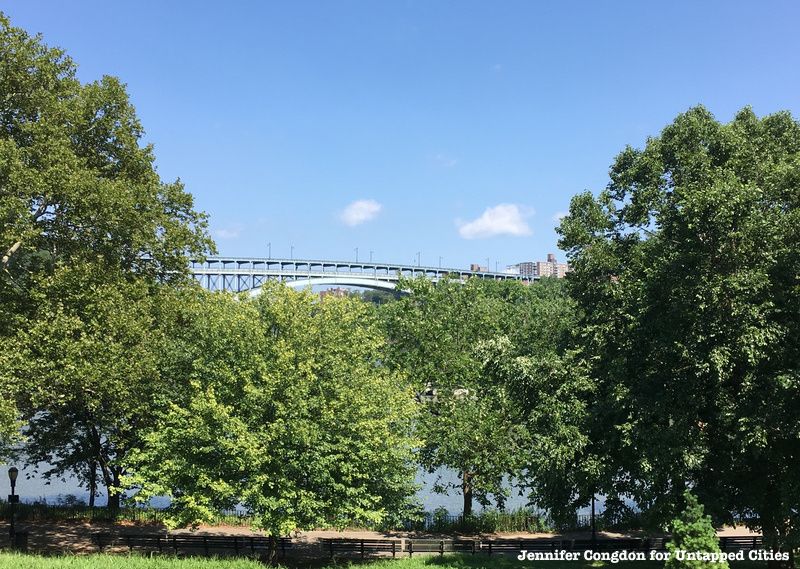

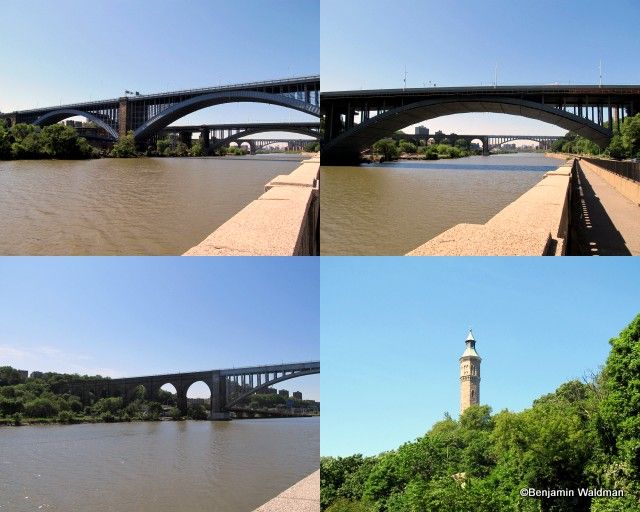

Designed by David B. Steinman and built as part of the Henry Hudson Parkway, the Henry Hudson Bridge was opened in 1936 to help alleviate congestion on the nearby Broadway Bridge. The steel arch toll span — named in honor of Henry Hudson’s voyage on the Half Moon, which was anchored near the site in 1609 — connects the Bronx with northern Manhattan, and spans the Spuyten Duyvil Creek.

Though not nearly spoken as much of as New York City’s other bridges, the Henry Hudson Bridge is a commanding city fixture, which harbors years of history. Here, we take a look at some of its most fascinating secrets, ranging from its construction to other little known engineering facts.

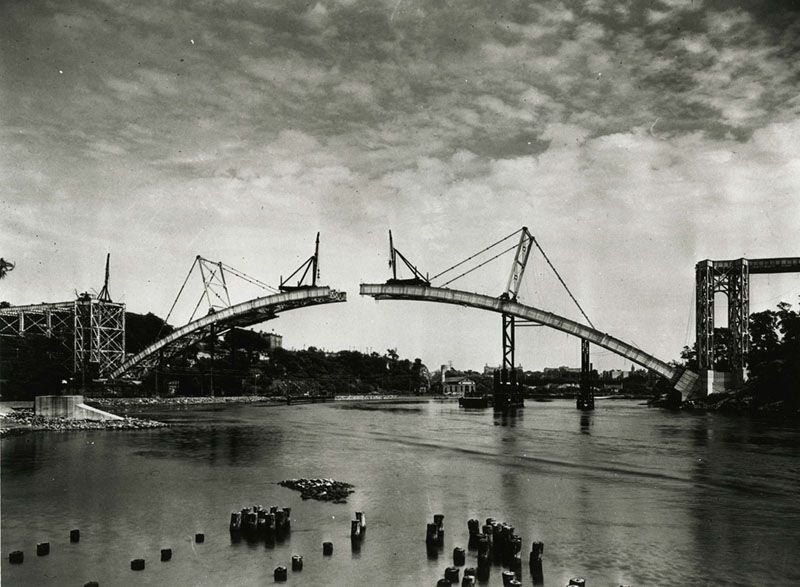

The Henry Hudson Bridge being constructed. Image via Wikimedia Commons: MTA

Today, over 60,000 cars utilize the Henry Hudson Bridge on a daily basis. However, it wasn’t initially intended to be a major thoroughfare. According to MTA Bridges and Tunnels President, Jim Ferrara, “The Henry Hudson was originally designed for leisurely weekend drives, but through the decades (it) has evolved into a vital transportation connection in the tri-state region.”

When it opened to traffic on December 12, 1936, the bridge was a single-deck structure that cost $4,949,000 to construct. At the time, master builder Robert Moses had planned for the span to be one level, but left the option to construct a second deck should traffic increase. This was to ensure that project would be more financeable. Eventually, an additional level was indeed needed: it opened to traffic on May 7, 1938, and cost approximately $2 million to build, funded by increasing toll revenue on the bridge. Northbound traffic flowed on the upper level while the original (lower) level carried southbound traffic. See photo of the bridge when it was only a single deck.

Although the Henry Hudson Bridge was built in the 1930s, the idea for the span was actually proposed as early as 1904. According to bridgesnyc.com, it was to be called the “Hendrik Hudson Memorial Bridge,” and was originally scheduled to be completed by 1909, in time to celebrate the 300th anniversary of Henry Hudson’s voyage. Designs were submitted, and postcards as well as paintings were created in anticipation for the bridge’s arrival. At the time, however, Spuyten Duyvil residents and other civic groups vehemently fought against its construction as they feared it would bring traffic to the nearby Bronx communities and destroy the “virgin forest” of Inwood Hill Park.

The anniversary eventually passed and years flew by. It wasn’t until the 1930s, when Robert Moses proposed the idea for the Henry Hudson Parkway alongside the bridge, that the idea actually came to fruition.

When the Henry Hudson Bridge opened in 1936, it cost drivers ten cents to cross it. During the first full year of the span’s operation, more than 17,000 vehicles paid the toll each day, even despite the fact that the free Broadway Bridge was located nearby. By year’s end, the bridge had collected $620,500 in tolls.

In November 2012, the Henry Hudson Bridge switched from traditional tollbooths to cashless tolling, becoming the site of the first pilot of All Electronic Tolling. Under this program, drivers no longer had to stop and hand over cash at the bridge, opting for an E-ZPass instead. Those without the passes were billed based on their license plate information. After the pilot in 2012, eight MTA-run bridges and tunnels converted to cashless tolling in 2017, starting with the Queens Midtown and Hugh L. Carey Tunnel in January and ending with the Throgs Neck and Bronx-Whitestone Bridges in September.

When it opened to traffic, the Henry Hudson Bridge was the longest plate girder arch and fixed arch bridge in the world, boasting an 840-feet-long main span and providing 143 feet of vertical clearance at mid-span, which allowed ships to navigate under it without a lift or swing mechanism.

At the time of its construction, it was considered an engineering marvel, especially given the fact that it took only 18 months to build. It has since been dethroned as the world’s longest fixed arch bridge, not even making it onto the list of the top 50 spans. (China’s Chaotianmen Bridge now claims the title at 1,811 feet.)

Image via Wikimedia Commons: MTA

Over the course of its lifespan, the Henry Hudson Bridge has been painted and repainted several times. According to The Bridges of New York (New York City)

by Sharon Reier, Steinman called for bridge engineers to create “beauty and harmony of composition through beauty of line, form and proportion, through color and illumination.” He was especially fond of painting his bridges in hues that blended in with the natural landscapes surrounding them.

As such, the Henry Hudson Bridge was originally painted a deep, forest green to blend in with the foliage of Riverside and Inwood Parks. It was later covered in aluminum gray, and then medium blue to blend in with the Harlem River before being repainted gray.

Tulip Tree under which the ‘sale’ of Manhattan took place in 1626. Image in public domain from Wikimedia Commons.

Like many of Robert Moses’ public work projects, the construction of the Henry Hudson Bridge was not without controversy. One such problem arose over an alleged Indian princess who taught pottery in the woods of Inwood Park. Public outcry arose over the princess’ working area and the removal of famous old trees that surrounded it — specifically an old, decayed tulip tree that reportedly dated back to when Henry Hudson sailed up the river in the Half Moon.

In describing the situation, Moses had stated sarcastically: “There were other trees, many decrepit. In the middle was a kiln where an Indian princess taught ceramics under dubious auspices. She had a son who didn’t work. Both were on relief, and the relief checks were delivered to the princess at a mail box fastened to a tree. The hullabaloo about disturbing the princess, the kiln, the old tulip tree, and other flora and fauna was terrific.”

To resolve the problem, a compromise had to be reached in which the good trees were saved and left on the hill. According to legend, Inwood Hill Park was also home to the tulip tree where Peter Minuit, the Director General of New Netherland, reportedly purchased Manhattan from the Lenape in exchange for a shipment of goods.

Image via Wikimedia: ChristiNYCa

On December 21, 1936, the opening of the Henry Hudson Bridge was celebrated with a ceremony that was combined with a birthday party for Mayor LaGuardia. As noted in Robert A. Caro’s The Power Broker, however, the occasion was not one of Moses’ most successful productions. Firstly, a “wild rainstorm” and fierce gusts of wind forced the crowd to move into the tiny administrative building on the bridge toll plaza.

Additionally, the event itself was overshadowed by news that King Edward VIII was giving up his throne to marry a commoner. Mayor LaGuardia, much to Moses’ dismay, insisted on listening to the broadcast of the abdication speech, thereby disrupting the ceremony.

Alongside the construction of the Hudson Memorial Bridge, there were plans to erect a statue of Hudson in time for the 300th anniversary celebration of his voyage and the 100th anniversary of Robert Fulton’s North River Steamboat. In 1909, crews broke ground for the project: sculptor Karl Bitter prepared a plaster model of Hudson, and architectural firm Babb, Cook and Welch designed the 100-foot-high Doric column as the statue’s support.

However, the project, alongside the construction of the bridge, was ultimately postponed due to a lack of funds. During this hiatus, Bitter died in a car accident in 1915. However, when Robert Moses finally revived plans for the bridge in the 1930s, the idea for the monument was resurrected along with it. Bitter’s student, sculptor Karl H. Gruppe, had to take over the assignment. He also helped complete Bitter’s Pulitzer Fountain in Manhattan’s Grand Army Plaza. Today, the statue is the only one of Henry Hudson you can find in New York City.

Although cashless tolling has become the standard for many New York City, the system didn’t always work out too well. As the initial testing site of cashless tolling, the Henry Hudson Bridge became quite a costly venture for the MTA. According to a 2014 New York Post, one third of drivers failed to honor the cashless toll system. By 2015, drivers had avoided $4 million in toll bills that were mailed to them.

The uncollected toll money also resulted in the accumulation of an additional $40 million in late fees and violation charges. Yet, despite this daunting figure, the MTA still considered the program a success, making the cashless tolling option a permanent fixture on the bridge in January 2015.

During the decades long hiatus between the initial proposal of the Henry Hudson Bridge to when the span was actually built, famed engineer David Steinman had conceptualized an entirely different version of the bridge. This iteration featured a main steel arch and elaborate masonry arch approaches, similar in design to the Washington (Heights) Bridge.

However, the Municipal Arts Society had an opposing opinion, arguing that the span would be out of place in the surrounded areas it was intended to connect. The classical arches, it argued, were unfit for the forest cliffs along the Harlem River.

Next, check out the Top 10 Secrets of Inwood Hill Park and read more about 11 of NYC’s Other Bridges.

Subscribe to our newsletter