As New Yorkers with a penchant for pocket parks and hidden gardens, it’s no surprise that Amster Yard has piqued our interest. Tucked away in Turtle Bay, and encased by the buildings at 211-215 East 49th Street, the lush “L-shaped” courtyard provides in-the-know New Yorkers with a refuge away from the chaos of the city.

While all the buildings that stand there today are only fifteen years old, Amster Yard’s historic significance actually dates all the way back to the 18th century. Over the past two hundred years, this small natural oasis — which harbors an auditorium and wine-tasting room, among other facilities underneath it — has drastically evolved, challenging the definition of landmark preservation and raising questions concerning how New York City should honor its architectural history.

The area where Amster Yard sits is said to have been the terminal stop of the 18th century Boston stage coach along the old Eastern Post Road, a system of mail-delivery routes between Manhattan and Boston. A one-story carpenter’s shop built in 1870 was one of the first buildings to be constructed on the property, and throughout the 19th century, a tenement, boarding house, and a couple of shacks were also built.

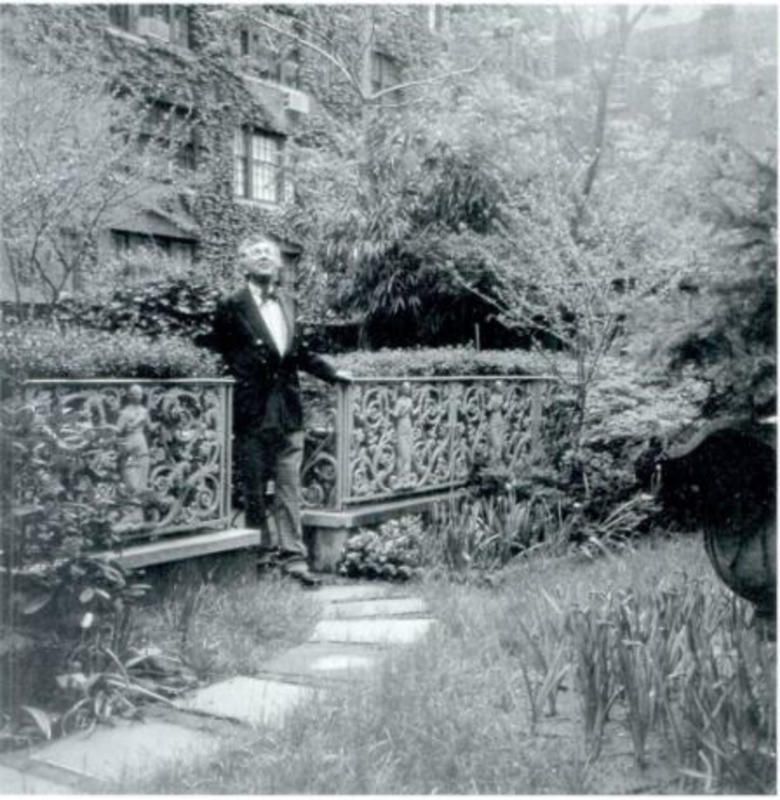

In 1944, the cluster of buildings on East 49th street was redeveloped by interior decorator James Amster, for whom the courtyard is named after. Amster turned the dissonant structures there into a harmonious array of one-to-four-story brick houses surrounding a lush courtyard garden. The front facing building had an arched alleyway leading to the enclosed, slate covered courtyard that was full of shrubbery and trees. Additionally, he adorned the painted brick facades of the renovated buildings — used as apartments, offices and stores — with hanging lamps, iron grille work, climbing ivy and black painted window trim. Amster himself called 49th Street home as did other notable figures, such as sculptor Isamu Noguchi and designer Billy Baldwin.

Due to the history and architectural charm added by Amster, the courtyard and surrounding buildings were given landmark status in 1966. The Landmarks Preservation Commission felt that its “picturesque” appeal made it one of “New York’s most beautiful inner courtyards,” and that Amster’s renovations were a prime example of adapting old buildings to fit contemporary needs. To celebrate, Amster threw a party, which was attended by neighbors, friends, and Amster Yard residents, such as fashion designers Norman Norell and John Moore.

After James Amster’s death in 1986, the glamorous allure of Amster Yard faded as commercial tenants trickled away and the last residential tenant left in 1992. Then in 1999, The Landmarks Preservation Commission, with support from the New York Landmarks Conservancy, approved plans from the Instituto Cervantes to make Amster Yard its New York base. After purchasing the property for $9 million, the nonprofit cultural group, created by the Spanish government, proposed to replace the least significant of the rear buildings with a new, three-story building, and to restore the remaining buildings and garden courtyard to their 1949 appearance.

Unfortunately, construction did not proceed as planned. On a routine visit to the site in 2002, Alex Herrera, the Director of Technical Services for the New York Landmarks Conservancy, found that most of the three rear buildings had been demolished and that the courtyard had been dug up. The buildings had been deemed unsound and unsalvageable by the project engineer who failed to notify the City or the Conservancy of new plans to knock the buildings down. This discovery upset local preservationists who bemoaned the lack of public review of the updated plans and the Commission’s decision not to fine the Instituto Cervantes. Mark Silberman, general counsel of the Commission, explained to The New York Times that no fines were applicable since the institute promised to rebuild the landmark exactly as it was.

The renovation team kept its promise and restored the courtyard and surrounding buildings to their post World War II glory, incorporating original pieces of iron work and detailing into the new construction. While some preservationists were still wary of calling the rebuilding of Amster Yard a success, former residents of the property were impressed by the accuracy of the replication; one former resident was even moved to tears.

On October 10, 2003, Crown Prince Felipe of Spain presided over a ceremony marking the completion of the multi-million dollar renovation and opening of the New York branch of the Instituto Cervantes. Underneath the restored courtyard is a 132-seat auditorium and the new surrounding buildings contain a 65,000-volume library, a 1,600-square-foot gallery, classrooms, offices and a wine-tasting room. The institute offers Spanish classes and a host of cultural programs, including lectures, book presentations, concerts, and art exhibits.

James Amster in his coutryard, 1960s. Image via Wikipedia Commons: New York School of Interior Design (Robert Moyer)

While some preservationists may count the demolition and reconstruction of Amster Yard as a loss, others find solace in the fact that the history and spirit of Amster’s original designs have been honored, and that New Yorkers can once again enjoy the natural respite of the courtyard.

Next, check out 13 NYC Courtyards Hidden in Plain Sight and the Top 10 Secrets of NYC’s Turtle Bay Neighborhood.