The Panorama of the City of New York, the 9,335-square-foot built-to-scale model of New York City, has long served as the Queens Museum’s “jewel in the crown,” but the institution itself harbors several treasures, as well as an interesting history that goes beyond its collection. Visitors who make the trek to Flushing Meadows-Corona Park to pay a visit to the museum will be treated to a plethora of relics from both World’s Fairs, exhibits covering a range of diverse subjects (with special regard for Queens residents) and a recently renovated space.

From its ties to the United Nations to its new architectural features, here are the top 10 secrets of the Queens Museum.

1. The U.N. Was Housed in the Queens Museum Building

Before the current United Nations complex was built, it had headquarters in locations all over New York City and even Long Island. These included the Hudson Hotel, Rockefeller Center, Hunter College’s Bronx Campus (now Lehman College), the Sperry Gyroscope Corporation headquarters on Long Island, and the New York City Building (now the Queens Museum).

Designed by architect Aymar Embury III for the 1939 World’s Fair, the New York Building was originally built to house the New York Pavilion, which featured displays about municipal agencies. Later, it became home to the General Assembly of the newly formed United Nations from 1946 to 1950, during which several defining moments took place, including the creation of UNICEF and the partitions of both Korea and Palestine. In 1964, following a renovation by architect Daniel Chait, the building was used again as the New York City Pavilion for the 1964 World’s Fair. Read more about each of the U.N.’s former locations here, and discover its many secrets.

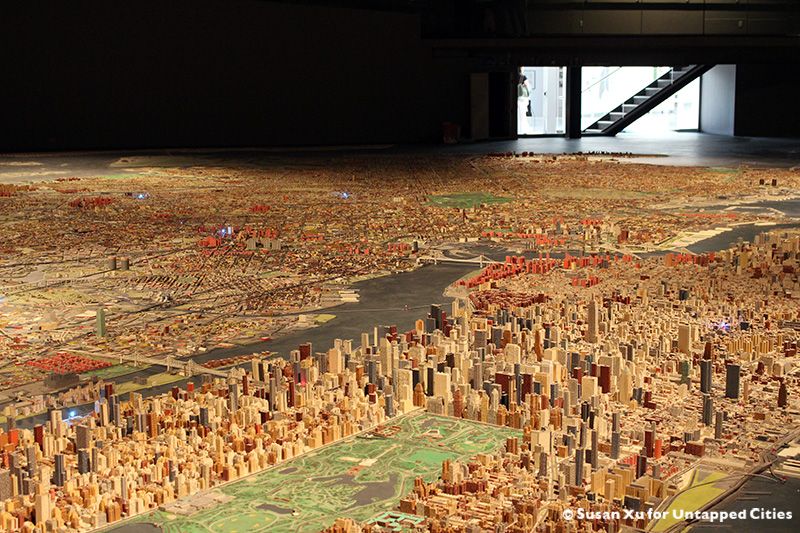

2. Adopt a Building From the Panorama

In 2009, the Queens Museum launched its Adopt-a-Building program, which allows visitors to “purchase” structures within the Panorama, commissioned by Robert Moses for the 1964 World’s Fair. Today, it boasts over 895,000 plastic and hand-painting wooden structures that represent every single building constructed in all five boroughs before 1992. For a suggested donation of $100, you can buy an apartment, complete with a title deed. However, if you’re seeking a small commercial building, warehouse or low-rise apartment building, you’ll have to fork up about $1,000.

As part of the Adopt-a-Building program, the Queens Museum also collects “New York Stories” from donors who have special connections to their purchases. The proceeds ultimately support the ongoing care and maintenance of the Panorama, and help to keep the model up to date. Late last year, the museum also brought back the Panorama’s legendary night lighting (read more below).

3. The Queens Museum Once Had an Ice Skating Rink

Included among the various attractions of the 1939 World’s Fair, the New York Building housed a roller rink on its north side as well as an ice skating rink on its south side, where extravagant ice shows took place. Once the World’s Fair ended, the building was transformed into a recreational center for the then newly created Flushing Meadows-Corona Park. It operated from 1941 to 1946.

However, when the United Nations General Assembly took over the building, substantial interior renovation was required. Both rinks were covered and an annex facility was erected on the north side of the building, which was used for the delegates’ dining room, an exhibition hall and a public cafeteria. The rest of the building housed offices, meeting rooms, and radio and television services. The stay, however, was short lived. When the United Nations moved to its permanent home along the East River in 1950, the New York Building once again became an ice and roller skating rink in 1952; it was also used for shows during the 1964 World’s Fair, in which Olympic figure skating champion Dick Button organized “Ice–Travaganza” performances within the facility.

Once the fair ended, the Flushing Meadows-Corona Park rink became the first year-round skating facility in the park system, while the Queens Museum (then known as the Queens Center for Art and Culture) was established in the northern half of the building in 1972. The ice skating rink was fixture of the building for 60 years until it was relocated to a new state-of-the-art recreational center in 2009.

4. The Only Surviving Building From Both World’s Fairs

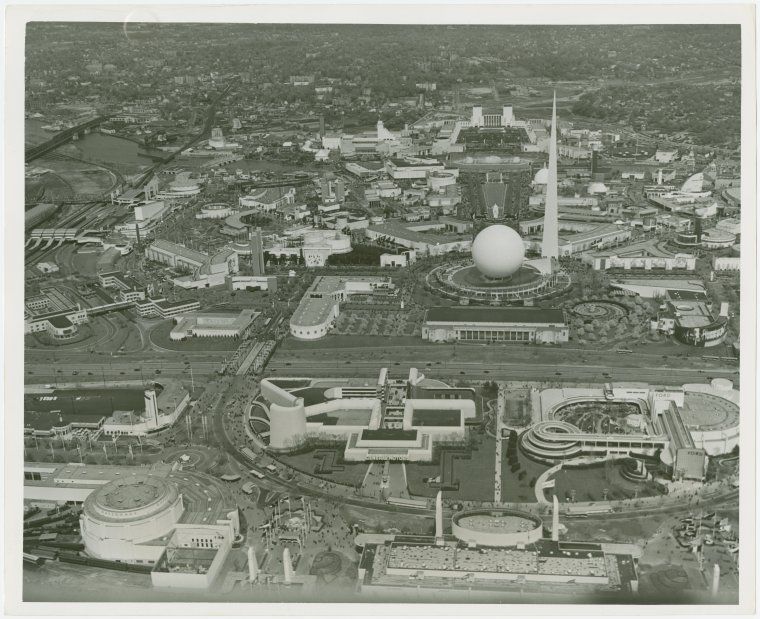

Photo from NYPL

Although there are many relics left over from both the 1939 and 1964 World’s Fairs that can still be seen today — amongst them, a collection of 10,000+ items and memorabilia housed on the second floor of Queens Museum itself — the actual New York Building that the museum occupies is, in fact, a remnant. It’s the only surviving building from both expositions, as well as the only substantial relic of the first fair. Today, a number of notable structures from the latter fair still survive, including the Unisphere, the New York State Pavilion, the Port Authority Building, and the Hall of Science.

As a team of history buffs and urban explorers, we’ve been geeking out over the World’s Fairs for some time now, which is partly the reason we’ve conceptualized an entire tour based around it. Book your tickets below:

Tour the Remnants of the World’s Fairs at Flushing Meadows-Corona Park

5. The Role of the Hanging Centerpiece

In November 2013, the Queens Museum finally completed its two-year and $69 million renovation by Grimshaw Architects, which essentially doubled its footprint to 105,000-square-feet and gave rise to a 48-foot tall atrium. One of the most notable features of the airy space is the “frosted-glass ‘lampshade'” that hangs above the atrium and below the museum’s skylight.

Although certainly a visual focus, the “glass ribs” are not just decorative. They actually help to reflect and manage the trajectory of the natural light to ensure it diffuses within the space. This is important since museum artifacts and art pieces can deteriorate in direct sunlight. According to Casimir Zdanius, Grimshaw’s head of industrial design, the angles of the panels (or louvers) were determined after conducting sun studies. Likewise, the strategically-aligned panels that act as a ceiling for the galleries help shift and shield the light that comes inside.

6. There’s an Outdoor Artist Pop Up

With an additional 50,000-square-feet of real estate from the renovation came new galleries, public event spaces, classrooms, a café and the construction of eight artist studios in the north wing of the building. Today, these studios foster the development of new work onsite and support both creative and professional development of artists.

Additionally, the Queens Museum, in partnership with ArtBuilt and NYCParks, has operated the Studio in the Park residency program since 2015. Under this unique program, artists are provided a $3,000 stipend, in addition to a 150-square-foot mobile studio space that is parked in a public city park, which they can use for six weeks. This year, the project sites will be: Seward Park in Lower Manhattan; Railroad Park in Morrisania, Bronx; and Flushing Meadows-Corona Park (adjacent to Queens Museum). You can apply until April 23rd, and the selected artists will be announced in May 2018. For more information about the residency, visit queensmuseum.org and check out our previous coverage.

7. Workers Who Installed the Panorama Left Their Names

As you can imagine, building the Panorama was no easy feat. With funding provided by the city of New York, Lester & Associates of West Nyack led the construction effort: it would take over 100 full-time workers, close to three years and $672,662.69 in 1964 U.S. Dollars (the equivalent of $5 million today) to complete the imposing model.

Given the amount of time and dedication it took to bring the Panorama to life, it should come as no surprise that a few workers wanted to leave their mark on the project. According to a Queens Museum statement, two workers actually left their names on the shrubbery. So next time you visit, keep and eye out for Bill and Ed on two islands in Jamaica Bay. Louise Weinberg, the archives manager at the museum, notes that women mostly glued buildings onto the Panorama and painted roads, while men laid out the streets, airports and parks, and constructed bridges.

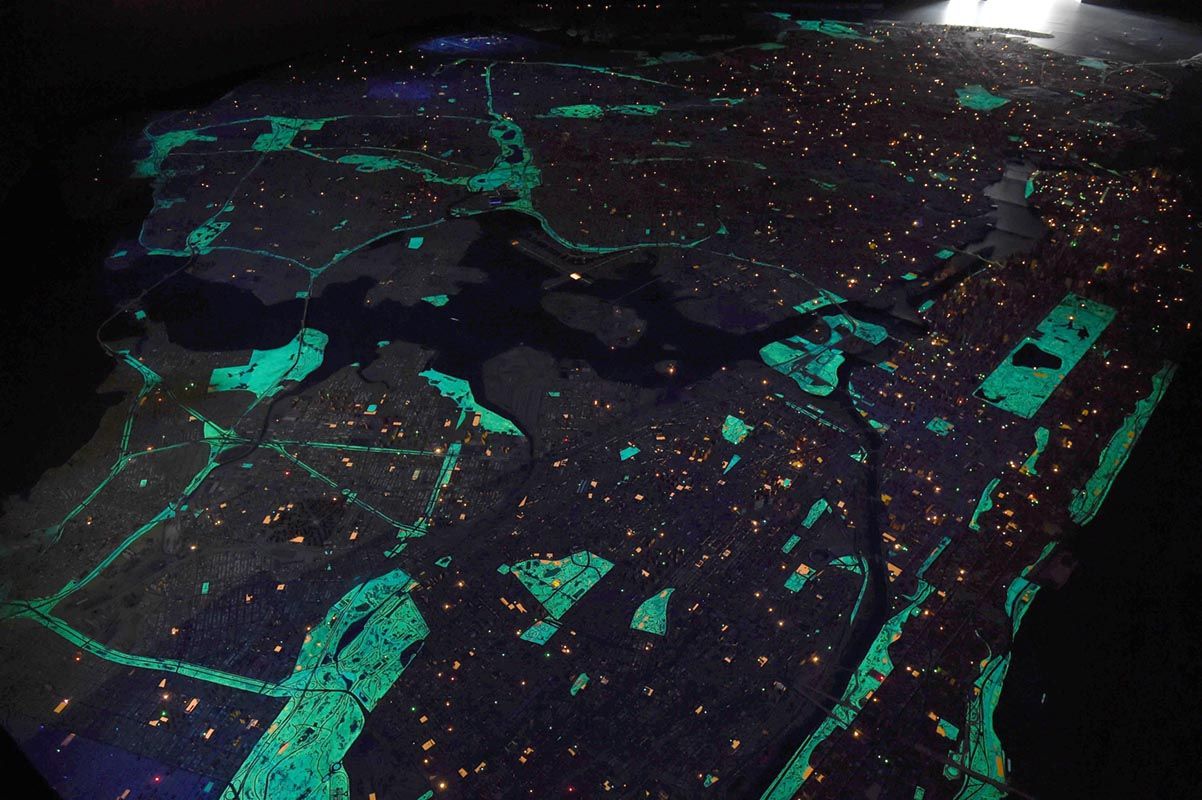

8. Panorama’s Iconic Black lighting Has Returned

Image by Gary Gershoff/Getty Images for Amazon Studios

In the decades since the Panorama’s installation, the attraction has been updated and renovated several times. The latest update is the replacement of its outdated lighting system, which was unveiled on October 25, 2017. The debut was timed to coincide with the U.S. release of the Todd Haynes’ film Wonderstruck, based on a novel by Brian Selznick, which follows the story of two children who set out on a quest to find answers about their family; scenes from the movie were partly filmed on the Panorama itself.

With funds provided by Amazon Studios, the state-of-the-art system introduces a contemporary and sustainable lighting scheme that incorporates LED lights, which have replaced the out-of-date black-light bulbs from the 1960s. Utilizing specialized software, the upgrade also brings back the legendary night-lighting of the Panorama. That means visitors can watch the model transition from day to night, and see the “psychedelic effect of black light” that transforms it into a glowing, after-dark experience. A press release notes that this effect was only seen by those who attended the 1964 World’s Fair or visited the exhibit before the early 1990s. Read more about it here.

9. See a Relief Map of the New York City Water Supply System

In anticipation for the 1939 World’s Fair, city agencies were invited to produce displays for the New York City Pavilion. This gave rise to a 540-square-feet and 27-piece Relief Map of the New York City Water Supply System and watershed, which The Department of Water Supply, Gas and Electricity (the predecessor to the NYC DEP) commissioned from the Cartographic Survey Force of the Works Progress Administration.

A budget of $100,000 (the equivalent to $1,759,000 in 2017) was set aside for the project, but the completed map was too large to fit within the allotted space inside the city pavilion. It was consequently never displayed at the World’s Fair, and has only made a public appearance at the Golden Anniversary Exposition in Manhattan’s Grand Central Palace. In 2008, after being stored away for decades, the map was restored to its original form, revealing still intact paint. It’s now on long-term loan at the Queens Museum.

10. Neustadt’s First Tiffany Glass Piece

In addition to the Panorama, the Queens Museum is noted for its stunning display of Tiffany glass samples, which were collected by Austrian-born American orthodontist Dr. Egon Neustadt. In the early 1900’s, Tiffany Studios was located in Corona, Queens, less than two miles away from where the Queens Museum stands today. Upon its closure in 1937, Neustadt took it upon himself to collect Tiffany glass, ultimately resulting in an expansive collection of over 200 lamps and more than a quarter of a million glass samples. Part of this collection was gifted to the New-York Historical Society while another portion is held at the Queens Museum.

Amongst the expansive collection at the Queens Museum is Neustadt’s very first Tiffany lamp, in a Daffodil pattern, which he purchased in 1935 for only $12.50. Check it out during A Passion for Tiffany Lamps on view at the museum’s Neustadt Gallery until September 2018. Also included in the show are shelves of Tiffany glass, rare examples of the Pond Lily globe shade and a peacock hanging shade.

Next, read more about the Panorama of the City of New York and discover the Top 10 Secrets of Flushing Meadows-Corona Park.