♀️ The Trailblazing Women of Wall Street

Women have long shaped Wall Street—even when history tried to write them out.

Recently, Untapped Cities Insiders were treated to a very special tour of the Landmark Loew’s Jersey Theater, located at Journal Square in Jersey City. The tour was led by Colin Egan, executive director and one of the founding members of Friend of the Loew’s, the group that saved the theater from demolition. Knowing that our members are interested in architectural secrets and off-limits places, Egan and his team spent the tour allowing us to access some very unique spots in the theater and sharing about the labor of love that has enabled the theater to be reopened. What’s incredible is that the restoration of the Loew’s Jersey is still ongoing, powered completely by volunteers.

Join Untapped Cities Insiders to join future events like this to New York City’s most off-limits places!

Here are 10 secrets of the theater that we learned on our visit!

In the 1920s, Loew’s built five “Wonder” theaters in the New York City area. These were grand movie palaces, designed with inspiration from Europe’s opera houses and noble palaces. The goal was to enable Americans to escape the humdrum of daily life, immersing themselves for hours on end taking in vaudeville theater and the movies.

The Loew’s Jersey opened on September 28, 1929, one month before the stock market crash. The land for the theater was acquired from Paramount studio and the theater was built at a cost of $2 million. The theater was designed by Rapp & Rapp, the architects of the Paramount in Times Square and the Brooklyn Paramount theater, now home to Long Island University’s basketball court.

Egan tells us that despite the Great Depression, the Loew’s theater chain did not suffer as deeply as other theaters because it had “the most valuable catalog.” Loew’s lost money only one year during the Depression, an impressive feat compared to its competitors.

In 1974, the main theater was subdivided into a triplex theater with sheetrock walls inserted into the center of the balcony. You can see the scars of that “renovation” today if you look up. This change rendered the theater unusable for live shows and the main stage got covered in trash, while the dressing rooms fell into serious disrepair, according to the Friends of the Loew’s. Then in 1986, the Loew’s Jersey Theater was closed and slated for demolition.

The scar of the conversion of the main auditorium can still be seen in the center aisle, if you look up

But even before the closure, the area between the stage and the balcony rail was abandoned with decades of dust and soot piling up. The original seats in this front area were ripped out and trashed. In the back of the theater, a rough layer of concrete had been poured over the original floor. There were leaking pipes causing additional damage.

Jersey City purchased the theater in 1993 but planned to simply “mothball” it. The Friend’s of the Loew’s, which started doing advocacy work on the theater in 1991, believed it would eventually be demolished due to neglect. To counteract this, the organization applied for a $1 million grant from the Jersey City Economic Development Corporation and won it, then successfully lobbied city government to provide a matching grant. This money was earmarked for stabilization of the building and so all interior work has been done through volunteers, with equipment and supplies provided through donations. Various volunteers had expertise, some fixed the original lighting board on the stage, another fixed the movable orchestra stage floor. Additional city funds were acquired to get the building up to code, including repairing fire escapes, and an additional grant was given by the Hudson County Open Space Trust Fund.

The restoration continues, all by hand, with the Friends of the Loew’s volunteers tackling new projects one by one. Friends of the Loew’s writes that in the year 2013, “a total of 5,107 hours of volunteer labor were donated.”

The Loew’s movie palaces took architectural inspiration from the palaces of Europe, but in execution, a lot of the over the top details were fake. “Virtually everything from the marble up is plaster,” Egan reveals, referring to a bottom band of real marble that circles the lobby. The rest is scagliola, or imitation marble made of plaster and painted to look like marble. The bronze is also fake, made of aluminum leaf!

The grand chandelier in the lobby is original, made of Czechoslovakian crystals. Egan tells us that the wiring was miraculously all in good shape and 80% of the crystals still remained, but only 20% of the lighting actually worked. Fortunately, Friends of the Loew’s had partial electrical plans for the chandelier and got it back in working condition, which took about a year.

The theater “was built to be maintained,” says Egan and he showed us what it looks like behind the dome of the lobby. In a space off the third floor, a door leads to a space behind the dome which allows for maintenance access. There’s a metal catwalk and a manual crank that lowers the chandelier! It takes thirty minutes to turn the wheel and get the chandelier down to ground level, which is how it was restored.

Although the Loew’s Jersey does not have its original organ, an identical Morton Wonder organ was found in a Chicago warehouse by the founder of the Garden State Theater Organ Society and purchased at a donation price through funds the founder had donated personally. This organ is one of five identical ones and was once in use at the Loew’s Paradise theater in the Bronx.

The organ has 1,800 pipes, miles of cables, and tens of thousands of parts, and came to the Loew’s Jersey in two tractor trailers. It was put back over the course of eleven years. The console rises up from the orchestra pit, and we were treated to a live performance that showcased the incredible range of sounds that can be created by the organ, sounds that would have animated silent films and vaudeville performances.

During the installation here, it was discovered that many parts actually had the words “Loew’s Jersey” written on it, and the pieces must have been accidentally included in the Bronx theater organ. “This was the console that was supposed to come here, but was a little delayed,” joked Egan.

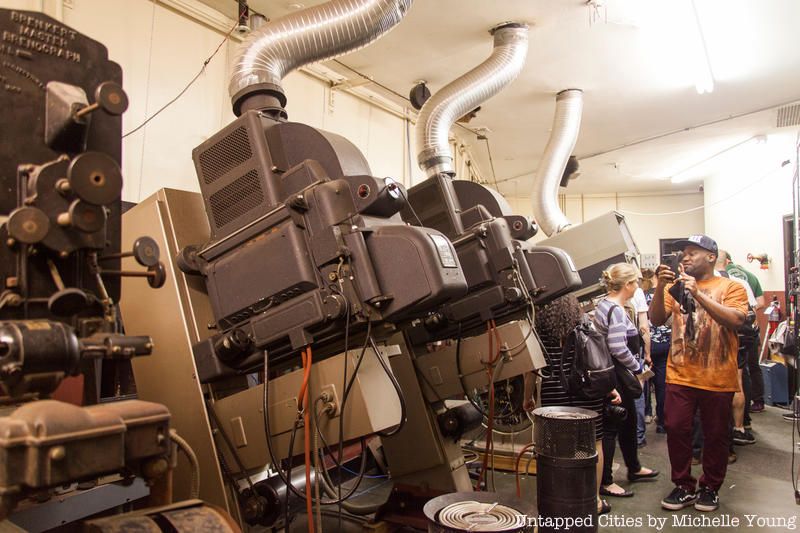

Up high in the Loew’s Jersey theater is the projection room, now a de facto museum for film projectors that have been donated to the theater over the years. One of the most special projectors is an Ashcraft Core-Lite High Intensity Projection Arc, manufactured in Long Island City, that has an accompanying turntable to play music. There are two Super Core-Lite projectors that play 35mm films and two of the oldest projectors in the space are the Brenkert Master Brenograph projectors manufactured in Detroit.

Down below the Loew’s Jersey theater are remnants of the original carbon dioxide system used to cool the theater, called the Carbonic Safety System of Refrigeration. The benefits of such a system included the ability to cool to temperatures far below what could be achieved with common refrigerants and the use of natural elements that are non toxic.

An advertising brochure from the American Carbonic Machinery Company, from Grand Rapids, Wisconsin in 1925 has a specific use case for “modern theatre cooling” which states:

An efficient air cooling system is today a necessity in an up-to-date theater because it is a financial balance wheel in the business of these institutions. The lull in the summer months in theatre-going activities is a tremendous financial burden and this can be made a profit earning period with the installation of a Carbonic Safety System because it maintains temperature of the auditorium within its limits of a well-defined comfort zone throughout the hottest months of the year.”

The carbonic machines seen above are actually a replacement of the original system, which broke down. Those units were simply dumped into an even lower level by cutting out the floor. Egan tells us that down a trap door (seen above), the original units sit there amidst a lot of dust. Today, the theater has a modern air conditioning system,

There is a room in the Loew’s Jersey theater that is dedicated to one thing: providing air for the organ with a device known as the Orgoblo. The Orgoblo was developed by the Spencer Turbine Company, advertised as “nearly noiseless” , with a custom motor designed for “exceptionally quiet operation,” a key boon to musical performances. The machine was also developed “along the lines of a “thoroughly scientific centrifugal turbine” designed with high efficiency in mind.

Off the projection room is a window where you can see the rooftop of the theater and the backside of the clock sculpture that tops the theater. The statues are mechanical and St. George on horseback stabs the dragon in fifteen minute intervals, when the clock is working.

Parts of the womens and mens lounges have been restored, though some of the original vanities no longer existed when Friend’s of the Loews started working. However, furniture was found haphazardly stored in other parts of the theater and brought to animate the womens lounge, such as the table and chair in front of the red curtain above. Many of the details of the mens lounge still exist (below) and Egan told us that for some reason, the details were remarkably intact despite the theater’s decline over the decades, something he believes is a testament to visitor’s respect of the architecture.

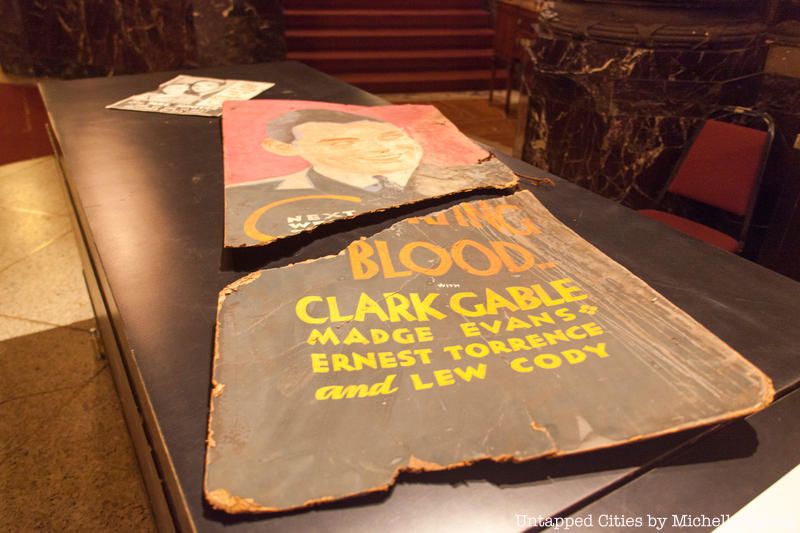

This poster for Sporting Blood, a film starring Clark Cable in 1931, was found facing in against a wall, looking like a piece of cardboard. As Egan describes, what’s “interesting in a building like this is how you find bits and pieces of history,” all over.

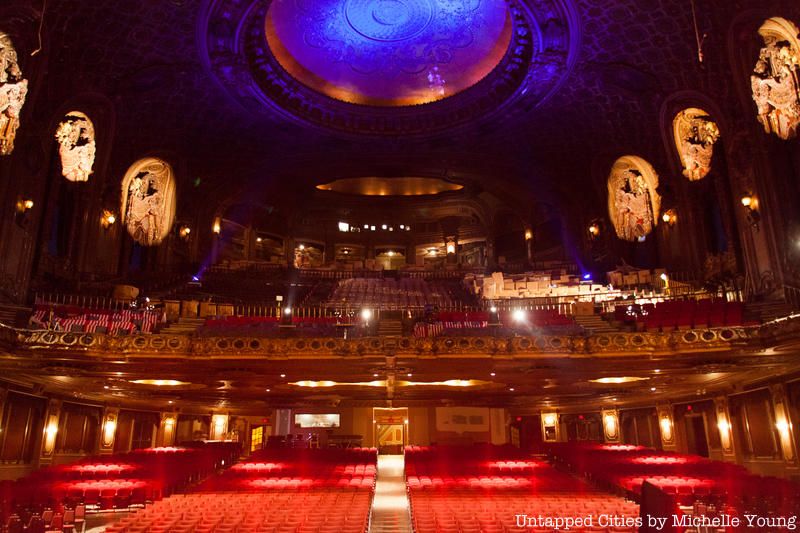

The ground floor of the theater is used for the guests who come to the events at the theater, but the balcony level is not yet ready. Here, Friends of the Loew’s is working on restoring more of the chairs and other restoration work on the level that has a capacity of 1,000 seats.

Opening the balcony level would drastically change the ability of the Loew’s Jersey to host more concerts, as many promoters have required more seats than available on the ground floor.

The original lighting board for the Loew’s Jersey is still in place and is now in working order, thanks to a volunteer of Friends of the Loew’s. Historically, lighting boards were located on the stage but as theater performances and movies evolved, it became a cumbersome spot for lighting. The Loew’s Jersey now has state of the art lighting and sound, which is controlled from a booth in the back of the theater. It is hoped that the original lighting board will be donated to a school or organization that can maintain it

The many curtains, and even the movie screen, is controlled through a system of pulleys that is still manually controlled. The staff of Friends of the Loew’s showed us how it works in action!

Here are additional photographs from our visit!

Join Untapped Cities Insiders to join future events like this to the area’s most off-limits places!

Subscribe to our newsletter