In the original 1858 Greensward Plan for Central Park, created by Frederick Law Olmstead and Calvert Vaux, an exhibition and music hall was planned for where you will now find visitors rocking out to live performances at the Summerstage. However, Olmstead and Vaux’s exhibition and music hall was never built at this site and performances were held at the old Bandstand on the Concert Ground at the end of the Mall. Where you will find Rumsey’s Playfield today, inside Central Park at Fifth Avenue and 72nd Street, Vaux designed a small building to house a 19th-century Ladies Refreshment Saloon. This building was then converted into a roaring nineteen-twenties casino, but no table games or slots were ever played there.

In 1864 Calvert Vaux designed a casino, or “little house” in Italian, that resembled the upstate country houses he once designed for his private architectural practice. The structure was a stone cottage that served as a Ladies’ Refreshment Saloon, where women who were not accompanied by men could rest and buy snacks and beverages in the park. Soon, men were also allowed into the saloon and it was renamed The Casino. With this new name, by 1882 the modest refreshment station had turned into a high-class restaurant that served fish, chicken, lamb, steaks, lobster, scallops, oysters, and Clams Casino, complimented by a wine list and champagnes and cordials like absinthe.

The restaurant became so popular with New Yorkers and tourists that it was expanded in 1894. The Central Park casino muscled its way through the early years of prohibition, but by the late 1920s was described by the New Yorker as being managed in “a somewhat dumpy nite-club style.” Up until 1928, the restaurant was run by theater producer Carl F. Zittel. When his lease was up, “gentleman” Mayor Jimmy Walker passed it lease over to restaurateur Sidney Solomon. Apparently, Walker owed Solomon a favor since Solomon had introduced Walker to his tailor. Mayor Walker enjoyed all the spoils of the Jazz Age, including fancy suits, speakeasies, and young pretty girls. It was joked that Walker spent more time at The Casino than he did in City Hall. Many park-goers feared that with Solomon’s acquisition of The Casino, the restaurant would become too exclusive and only cater to a wealthy clientele. Their fears were soon realized.

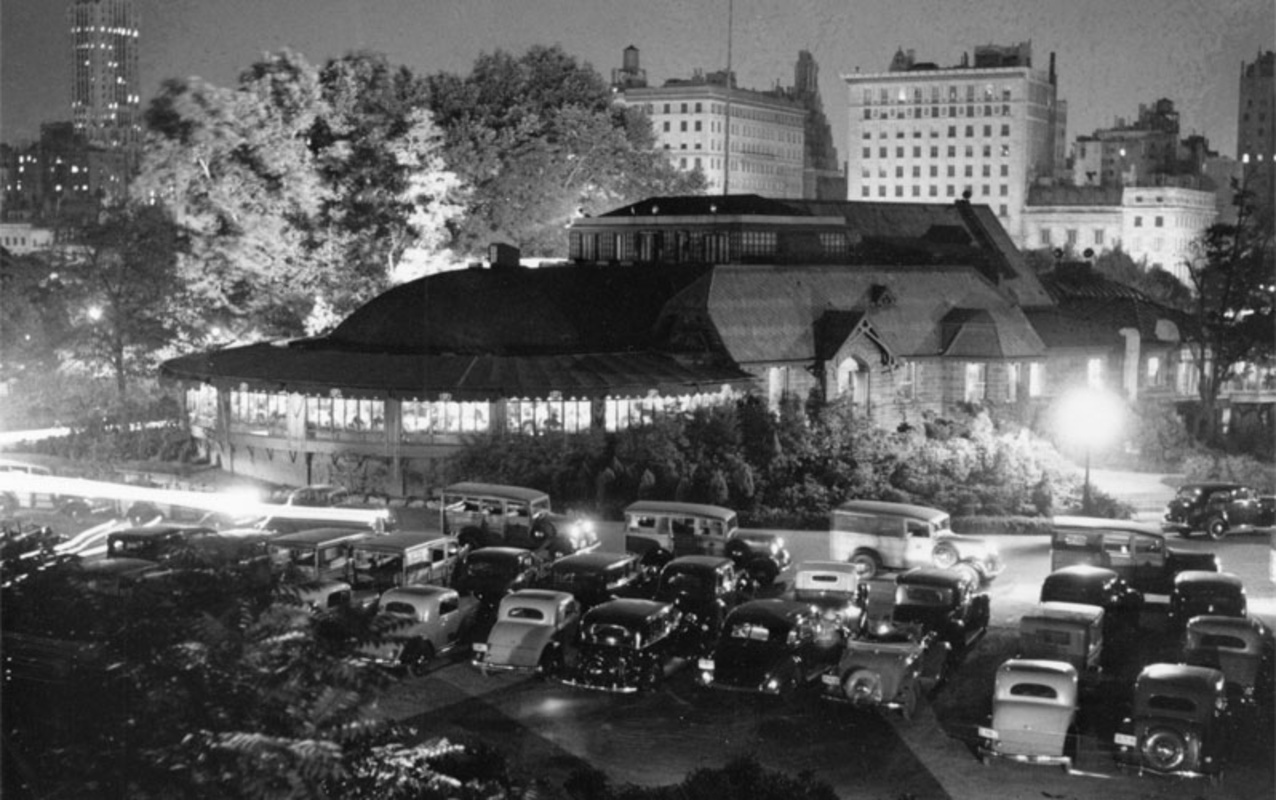

The new version of the Central Park casino premiered after a $500,000 renovation which brought the additions of a tulip pavilion, an orange terrace, a silver conservatory, and most notably a black-glass Art Deco ballroom designed by Josef Urban, the esteemed Viennese interior designer. Solomon described the changes to the Casino “not as just a renovation,” but “something which has never before existed so perfectly in the world.” The restaurant sat 600 people and had enough parking space for 300 cars. In a New York Times article from 1929 detailing the lavish re-grand opening, management said they wanted The Casino to become “a place for the fashionable and fastidious,” with “new standards of elegance and beauty.” The opening night dinner was attended by guests who were handpicked by the restaurant’s board of governors which included well-known names like producers Florenz Ziegfeld and Adolph Zukor. Each attendee shelled out $10 for a night of fine cuisine, prepared by chefs who once cooked for Louis Rothschild, and entertainment by Emil Coleman and his band in the ballroom and a band from Boston in the pavilion, which Josef Urban said he designed with “the joyousness of a wind through young leaves.”

Though the Casino catered to an exclusive nightlife scene, during the day the restaurant was open to the public and served food a la carte. However, the high price point of the fare – in 1934 a coffee cost 40 cents – in the midst of the Depression, led many to feel that the restaurant was not serving the needs of the general public, and after all, it was in a public park. The new commissioner of New York City’s Department of Parks Robert Moses made it his mission to, literally, take the Casino down.

After a series of court hearings, it was unanimously decided by the Appellate Division of the Supreme Court in 1934 that Moses had the authority to raze the Central Park Casino building. The ruling stated that Moses could “remove for other park purposes buildings which have been erected solely as incidental to park uses such as restaurants, baths, boat houses, and similar structures.” The restauranteurs contended that destroying the Casino would be a waste of public property and that Moses’s proposal for a children’s playground at the site was ill-advised since it was so near street crossings in the park. Nevertheless, the Casino was torn down in 1935, and two years later, in May 1937, the two-acre Mary Harriman Rumsey Playground for children, now known as Rumsey Playfield, was opened. The playground was named for a founder of the Community Councils of the City of New York. While Moses saw the destruction of the Casino as a victory for the parking going public, some saw it as a shameful loss of a Calvert Vaux-designed building and a waste of public property. Justice Martin, who presided over Moses’ appeal to knock down the Central Park casino, made a foreshadowing statement when he noted that giving Moses the authority to knock down any building without the approval of some type of board was “a very dangerous power.”

Next, check out Find the Authentic Survey Bolt from NYC”s Original 1811 STreet Grid in Central Park