NYC’s Forgotten ‘War on Christmas Trees’

Discover how an obscure holiday crackdown affects festive street vendors today!

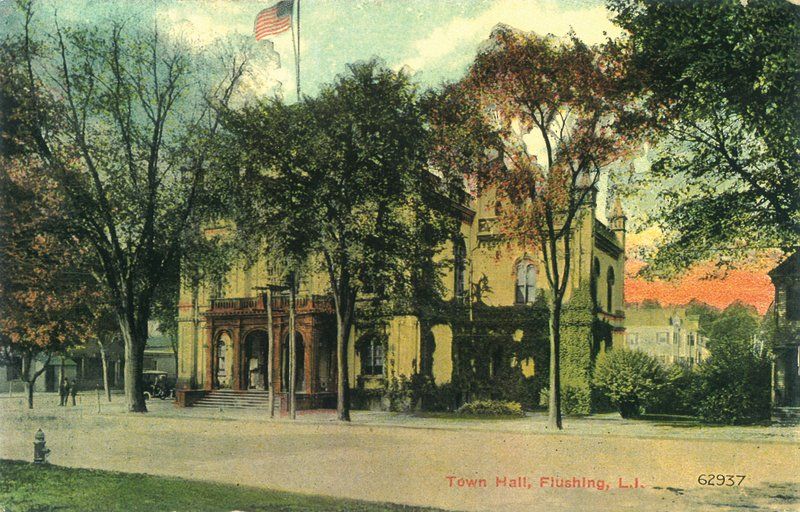

When a New Yorker thinks of Flushing, images of the city’s secondary Chinatown and Koreatown will likely emerge. But Flushing’s rich history is apparent in the pockets of historic, landmarked buildings situated along Northern Boulevard, as well as sprinkled throughout the neighborhood. One of these is Flushing Town Hall, built during the Civil War. It is located between Linden Place and Leavitt Street across the street from Flushing Quaker Meeting House, which dates to 1619. Though the area around it has changed dramatically in the century and a half since the first cornerstone was laid, the Romanesque Revival-style building retains both its stateliness and its “striking picturesqueness,” as the Landmarks Preservation Commission described it in its designation report in 1968.

Still, Flushing Town Hall was characterized by stretches of vacancy and deterioration, with its walls testament to a palimpsest of uses, and was saved thanks to local activism and support. In this article, discover the story of Flushing Town Hall, now home to a multi-cultural art venue run by the Flushing Council on Culture & the Arts, with little known secrets and fun facts about the building’s history. The Flushing Town Hall is part of the Cultural Institutions Group (CIG), as well as an affiliate of the Smithsonian Institute, with an extensive variety of events, education programs, exhibitions and more.

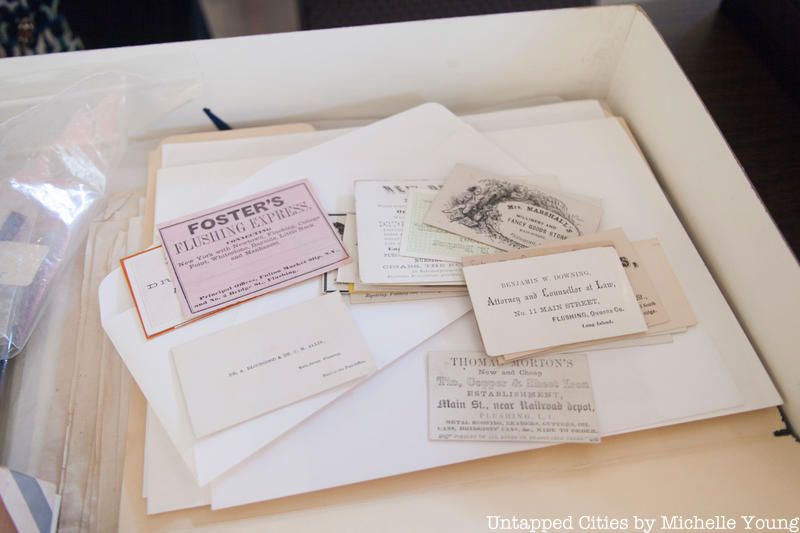

The cornerstone of Flushing Town Hall was laid on June 7th, 1862. Inside this cornerstone was placed various documents and objects relevant to the time period and the town. The items include buttons, coins, a pen, a Bible, newspaper clippings, business cards, a history of Flushing, the original document that organized the Flushing Fire Department, and more.

In 1962, during restoration work on the portico the time capsule was rediscovered. The items were donated to the Museum of the City of New York and were later given back to Flushing Council on Culture & the Arts.

Crowds in front of Flushing Town Hall during the trial of Captain Peter Hains Jr. and Thornton Hains Jenkins. Photo courtesy Flushing Town Hall archives

In the Victorian era, crimes of passion were generally acquitted in the court of law through the defense of “Dementia Americana,” known also as “the unwritten law.” This temporary derangement of course lasted just long enough for husbands to kill their wife’s lover, a defense strategy most famously used successfully in the murder of architect Stanford White by Harry Thaw over the actress Evelyn Nesbit.

In a case that fascinated New York, Captain Peter Hains Jr., with assistance from his novelist brother Thornton Hains Jenkins, killed William Annis, a magazine editor and friend of Captain Hains, at the Bayside yacht club by shooting him eight times. Thornton Hains had written to Captain Hains while he worked abroad about orgies allegedly happening at Fort Hamilton in Brooklyn involving the Captain’s wife, Claudia Libbey. The Captain became convinced over the next two years that an affair was indeed happening, contrary to his wife’s denials.

So convinced was the Captain of his ability to get away with the crime, he “sat on a bench and waited calmly for the police to arrive,” reports the New York Times. Thornton Hains tried a defense of “dual insanity,” or folie à deux in French meaning that Captain Hains’ derangement had been contagiously spread to him, also temporarily, of course.

In a dramatic turn of events, the jurors at Flushing Town Hall convicted Captain Hains of manslaughter, and he received an eight year sentence at Sing Sing while Thornton Hains was acquitted. The New York Times writes that the shift of opinion the case had on law made quite an impact, and that “Thornton Hains was probably the last man in New York State acquitted on the grounds of ‘the unwritten law,’ albeit vicariously.”

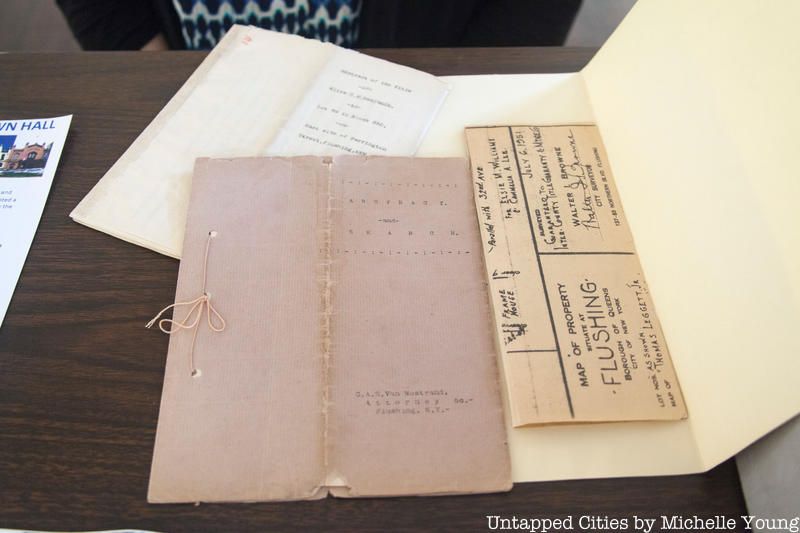

In the archives of Flushing Town Hall, the original deeds and affiliated documents for the Flushing Town Hall still exist. One document reviews the history of ownership of the property, including mortgage details, and another shows a map.

Before the Town Hall was built, the town meetings were held in a public tavern and the first election was held in the schoolhouse of St. George’s Church.

Photograph Courtesy of Queens Borough Public Library, Long Island Division

According to the Flushing Town Hall’s history, “the people of Flushing wanted a place of pride to welcome home their troops from the Civil War, a gathering place to celebrate the beauty of life and to cope with life’s struggles.” As such, the main hall took up a large portion of the building itself. During a renovation, the proscenium of the stage was rediscovered behind a wall. It had been sealed up after the Town Hall was converted into a courthouse. With all the changes in use, this particular space inside the Town Hall went from theater to courthouse and back to theater.

In its current state, the theater has all removable seats and risers, making the theater adaptable to numerous types of performances and events. This flexibility provides a direct link back to how the space would have been used during its town hall days.

“Many people still think that we’re the town hall,” says Ellen Kodadek, Executive and Artistic Director at Flushing Town Hall, “so people come in all the time and want a marriage certificate, or a work permit. It happens constantly and we feel a little badly that we have to turn them away.” However, the Flushing Town Hall only served as a town hall for 38 years, from 1862 to 1898, when the consolidation of New York City happened. The City took over the building from the former town of Flushing and turned it into a court house.

The building was also used as a police precinct for the 1964/65 World’s Fair, by the Department of Public Welfare, the Highway Bureau, the Big Sisters of Queens, the Flushing Historical Society, and the Girl Scouts. It has also served as a mustering hall during the Civil War, a ballroom, a bank, a library, a dinner theater, a jazz club, and its current use as an arts and cultural center.

Flushing Town Hall was used as a courthouse until 1960. The Landmarks Preservation Commission landmark designation in 1967 was an effort to save the building, and the National Park Service named the hall a historic site in 1972. From 1962 to 1976, the building remained vacant, apart from one year as a dinner theater. By 1989, the building had deteriorated significantly, with graffiti, a damaged facade, and broken and missing windows. In June of that year, the Civil Court evicted the sub-tenant and a year later, the Flushing Council on Culture & the Arts was awarded stewardship of the building to renew it and turn it into a multi-cultural arts center. In the 1990s, the Town Hall was stabilized, revitalized and restored thanks to local and state funds.

There was once an external staircase that connected to the second floor of the rear of Flushing Town Hall that would bring up detainees who needed to be present for trial. They would be held in jail cells that still exist inside Flushing Town Hall that have been converted in the modern era into changing rooms and green rooms for shows. The slatted metal door of the cells still exist, covered over by curtains, and some of the brick inside the rooms is original. In the smaller changing room/cell, you can see the outline of where the staircase was bricked up. Another jail cell that once existed was turned into the elevator shaft.

Postcard scan courtesy Flushing Town Hall

“There was a period of time where the building had actually been painted,” says Kodadek. It was quite a contentious issue in one of the restorations whether to keep the paint on the building or to remove it, and ultimately it was decided to return the building back to its original brick state. Another paint debate took place over the floor of the front balcony, which is not a location often viewed by visitors and certainly can not be seen by a passerby. However, the Landmarks Preservation Commission performed tests to determine the original color – a pinkish red color. “When you work in an old building like this, you learn new things all the time,” Kodadek tells us.

Emerging or mid-career artists can apply for a Space Grant at Flushing Town Hall, which offers free use of the facility, including the theater. Artists that have been part of this program include a juggler, circus artists, choreographers, and videographers. There is also a Composer Artist in Residence program called Exploring the Metropolis, which offers space and a stipend.

Vintage photo courtesy Flushing Town Hall

The gallery space on the first floor of Flushing Town Hall has served as both an office space and a jazz club. Historic photos show the walls completely covered in wooden slats with a tin coffered ceiling, which still exists. The transformation of spaces in Flushing Town Hall really reflect its long history of diverse use. Some of the back offices used to be a gallery, Kodadek says.

Here is what part of the galleries look like today:

Garden of Flushing Town Hall

Flushing Town Hall has received numerous notable guests over the years. In the 1840s, P.T. Barnum served as the hall’s impressario with Tom Thumb as his star. Frederick Douglass, the former slave and abolitionist, spoke here in 1865 about the role of African American in the pre-civiil war era with tickets at 25 cents a person. Two United States Presidents also spoke here – Theodore Roosevelt and Ulysses S. Grant.

Next, check out the Top 10 Secrets of Flushing.

Subscribe to our newsletter