Name a Rat (or Roach) After Your Ex (or Lover) for Valentine's Day

Need ideas for a Valentine's Day gift? This one is sure to surprise!

Stanford White, the famed architect of the prolific firm McKim, Mead and White, designed an exorbitant amount of buildings in New York City throughout the Gilded Age. From places of entertainment and the homes of New York’s elite, to utilitarian structures and a college campus, White’s designs varied in scale and purpose, but always had a sense of grandeur and great attention to detail. Here are 20 past and present buildings in New York City that were designed by Stanford White.

The Players is a members only social club that was founded in 1889 by Edwin Booth, (brother of the infamous assassin John Wilkes Booth) one of the most renowned American actors of the 19th century, and fifteen illustrious friends and colleagues including Mark Twain and General William T. Sherman. Booth commissioned another famous friend, architect Stanford White, to redesign the façade and interiors of a Gothic-Revival mansion at 16 Gramercy Park South to make a home for his new club. This same building, with dark wood interiors and balconies that overlook the private park, has served generations of actors, artists, writers and arts aficionados who have been part of the club over the past nearly 130 years. Booth actually lived in an apartment on the third floor that remains virtually unaltered since he died on June 7th, 1893.

Current notable members of this social club include Jimmy Fallon, Ethan Hawke and Tommy Lee Jones, whose portraits hang in the club’s grand staircase.If you want to explore the Stanford White interiors of this clubhouse, you can join Untapped Cities’ upcoming Special Access Tour of the Players Club!

Insider Tour of the Players Club on Gramercy Park

One of Stanford White’s most iconic designs is that of the Washington Square Arch in Washington Square Park, and he designed it for free! Before the construction of the marble arch in 1892 a temporary arch made of wood, papier-mache and white plaster, also designed by White, was erected in 1889 to celebrate the centennial of President George Washington’s inauguration. Residents grew fond of the arch and raised funds to build permanent one.

For the new marble version of the arch, White drew inspiration from sites in Rome and Paris‘s Arc de Triomphe which went up fifty years prior. While White wanted his arch to look more modern and simple than the one in Paris, he did incorporate antique elements such as allegorical figures, bands of decorative motifs, and wreaths of laurel. The relief work on the arch was done by sculptor Frederick MacMonnies and the eagles perched on top were created by Phillippe Martiny. Two sculpture of Washington, as Commander in Chief and as President, created by Hermon MacNeil and Alexander Stirling Calder were added years later.

Image via Wikimedia Commons

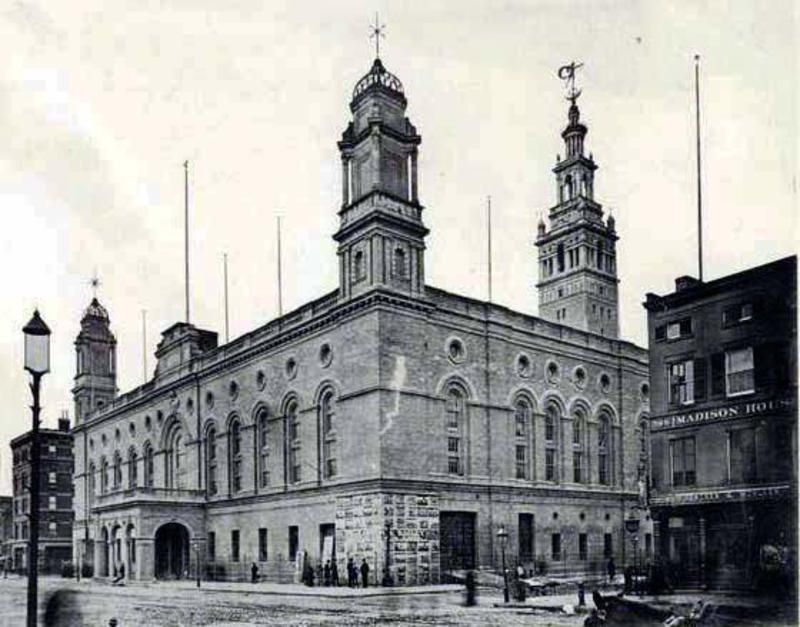

Stanford White designed the second of four Madison Square Gardens that have existed in various locations around New York City. The first arena to bear the name was P.T. Barnum’s “Great Roman Hippodrome” near Madison Square Park. The building became Madison Square Garden when it was purchased by William Kissam Vanderbilt in 1879. That building was demolished in 1889 and replaced the next year by White’s Moorish styled theater. With funding from big name New Yorkers like Andrew Carnegie, the Astors, and J.P. Morgan, White went all out.

The 33-story minaret White designed for the building, modeled after the campanille of the Giralda in Seville, Spain, made the Garden the second-tallest skyscraper in the city. White even had his own personal apartment inside the tower. The tower was topped by a 13-foot statue of Roman goddess Diana by Augustus Saint-Gaudens. The statue was nude, which caused outrage from the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice and forced the sculptor to “cover her modest” with drapery. The drapery blew off in the wind only a few weeks after it was placed on the statue.

White’s Madison Square Garden held a cafe, New York City’s largest restaurant, a rooftop theater, and sports area which all told held 8,000 people. It was at lavish rooftop theater that White’s lavish life came to end. In 1907 White was murdered by Harry Thaw, the jealous millionaire husband of Evelyn Nesbitt, a former lover of Stanford White. White’s Garden was torn down in 1925 and today it is the site of the New York Life Insurance building.

Stanford White described the Metropolitan Club building for the New York Times as “unrivaled in its size” with “an appearance unlike that of any building in New York.” Located at 1 East 60th Street on the corner of 5th Avenue, the Metropolitan Club was established in 1891 by a group of “distinguished gentlemen, prominent in the civic, commercial, financial, and social life of the City” which included William K. Vanderbilt, William C. Whitney, Cornelius Vanderbilt, and the club’s first president J.P. Morgan.

To purchase the land on which the clubhouse stands each of the twenty-five founding members contributed $5,000. The land was at the foot of “Millionaire’s Row,” the fashionable uptown district characterized by the Gilded-Age estates of the wealthy upper class. The Italian Renaissance styled white marble clubhouse, which was designated as a landmark in 1979, cost nearly $2 million to build, which amounts to just over $48 million today. While the exterior design of the building showed restraint in design, the inside boasted extravagance. No expense was spared for the club’s amenities which include a dining hall, a breakfast room, smoking room, a reading room, two card rooms, three large private dining rooms, 22 suites for overnight guests, a bowling alley, wine rooms, a roof garden and even a ladies’ annex. The inside is covered in gilded flourishes, marble, coffered and mural covered ceilings, stain glass windows, and wrought iron railings that run along the fifteen foot wide grand staircase.

Image via Wikimedia Commons, Detroit Publishing Co. collection at the Library of Congress

The original McKim, Mead and White designed station built for the Pennsylvania Railroad opened in phases and was officially completed in 1910. The massive Beaux-Arts structure was an architectural wonder that spanned two city blocks and 8 acres of land making it the largest indoor public space in the world at the time. The station served as the Manhattan terminus for Long Island Railroad riders who now had direct access to the city via the new and innovative East River Tunnels. Trains also came in on the Pennsylvania Railroad, New Haven and the Lehigh Valley Railroad lines.

The colossal station boasted large windows and a stunning glass atrium which let in natural light that Penn Station commuters today can only dream of. The front exterior was adorned with a colonnade of Roman columns modeled after landmarks such as the Acropolis of Athens while the other sides were inspired by St. Peter’s Square in Vatican City, as well as from the Bank of England headquarters. Despite fervent attempts to preserve the station, it was demolished in the mid-1960s to make way for the present Madison Square Garden and Pennsylvania Plaza. We are left only to wonder what could have been if the original structure were still here today. However, there are still many remnants of the original which can still be found in the current station. You can explore these remnants for yourself on our walking tour of Penn Station!

Tour of the Remnants of Penn Station

The New York Herald Building in 1895. Image from Library of Congress.

In the 1890s, James Gordon Bennet Jr., the son of The New York Herald newspaper founder James Gordon Bennet Sr., decided to move the paper’s headquarters away from “Newspaper Row,” north to a triangular plot of land at the intersection of Broadway and 6th Avenue between 35th and 36th Streets. After signing a thirty year lease on the land, he commissioned Stanford White to design the new headquarters.

White based his design on the 1476 Venetian Renaissance Palazzo del Consiglio in Verona. Some criticized it for being “too perfect” a copy, but the extravagant building received mostly positive reviews. The area surrounding the building came to be known as Herald Square and people would flock to peek through the building’s large arched windows to watch the printers at work. Lining the roof of the building were twenty-six four-foot bronze owls, an animal which Bennet made the symbol of the newspaper. The birds at the corners of the roof had green glass eyes that glowed on and off with the toll of the Herald’s clock. Bennet paid for these sculptures himself so he would have full ownership of them.

By the end of the thirty year lease the Herald was acquired by The New York Tribune and the building was demolished in two stages. According to the Daytonian in Manhattan, the northern half went down in 1928 and the rest was replaced with a four-story structure designed by architect H. Craig Severance in 1940.

Bronx Community College is the former University Heights campus of New York University. In the 1890s, NYU purchased the Mali Estate, a 40-acre site in the Bronx on a bluff overlooking the Harlem River, in order to create a sprawling college campus with monumental buildings, open lawns, fresh air and river views, features that just weren’t possible at its crowded Greenwich Village campus. All of the campus’ Beaux-Arts buildings were designed by Standford White.

Stanford White‘s master plan for the University Heights campus included several buildings arranged around a quadrangle. Designed in a Beaux-Arts style described as “American Renaissance,” they were completed between 1894 and 1912. The centerpiece of the plan was Gould Memorial Library built in 1897, which features a dome that has become an iconic symbol of the campus. Inspiration for the domed structure came from the Roman Pantheon. Inside, the library is decorated with wood, bronze, marble, stone and Tiffany glass. The landmark commission notes that “the importance of this notable building lies in its achievement of great Classical dignity and monumental grandeur.” The library is surrounded by The Hall of Fame, a semicircular open air colonnade, also designed by White, that features the busts of famous American men and women.

The campus, with thirty-four buildings spread over forty-five acres, is the only community college in the United States, and only college in New York State, to be declared a National Historic Landmark.

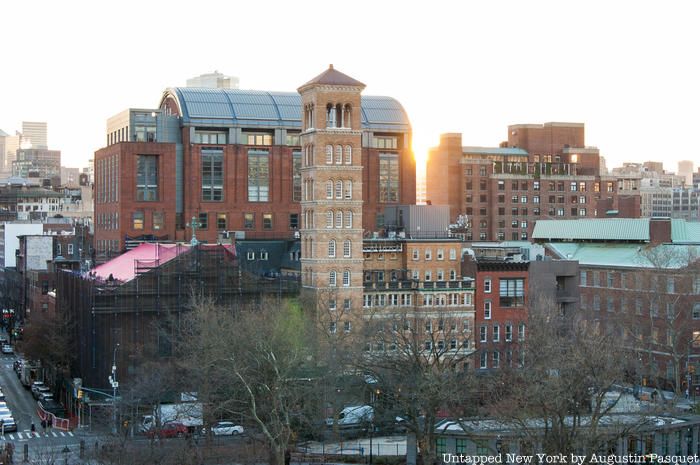

Located on 12th Avenue and 59th Street, the IRT Powerhouse is a stunning 1904 Beaux-Arts style building, designed by Stanford White. When it opened, it was the largest powerhouse in the world, spanning an entire city block from from 58th to 59th Street and Eleventh to Twelfth Avenue. The powerhouse provided electricity for the first subway line, which ran along the west side of Manhattan. It was sold in 1959 to Consolidated Edison and became a steam-generating plant since by then the subway system required less electricity.

Although the last remaining smokestacks were removed by Con Edison in 2009, the structure still commands a lofty presence thanks to its mammoth size, pivotal location and stunning architecture. It is for these reasons that developers have been eying the site over the years, seeking to re-adapt it as a space for public events, recreation, performances and more. The structure was given landmark status in 2017. The Historic Districts Council noted, “This monumental structure is a remarkable example of Beaux-Arts design applied to a utilitarian building; its architectural grandeur meant to convince the public to embrace the subway, a major new mode of transportation back in 1904. Designed as a showpiece, it now stands as a monument to progress and rapid transit.”

The headquarters of the Bowery Savings Bank at 130 Bowery is heralded by the Landmarks Preservation Commission as one of the first examples of “new classicism,” a style established at The World’s Columbian Exposition, at Chicago in 1893 and that it “is a fine, dignified expression of a New York banking house and that in its skillful use of site, its good proportions, fine detail and sculpture, it reflects credit on the well-known architectural firm which designed it.” The building sits on an L-shaped lot and was designated a landmark in 1966.

At the time of its construction it was one of the city’s first savings banks and at the time of its landmark designation, it was reputed to be the only bank in New York which retained a branch on the site where it first started business. Today the former bank has has been repurposed into Capitale, a restaurant and event space.

With financial help from John D. Rockefeller, Baptist preacher Edward Judson was able to hire Stanford White to design him a church on the corner of Washington Square South. The exterior, with terra cotta ornamentation, yellow Roman brick, marble panels, and a campanile, is reminiscent of early Renaissance churches in Italy, and was designed in that style to appeal to Italian parishioners. Completed in 1892, the landmarked church in Greenwich Village still serves as a place of worship and as a public center for the arts. The church’s gymnasium even serves as a theater space.

The Cable Building gets its name from the industry of its first tenant, the Metropolitan Traction Company, a company that leased and operated cable car lines in Manhattan. The lower floors of this nine-story building held machinery while the upper levels contained office space. Inside the building, completed in 1894, there were once four 32-foot steam powered wheels that moved a network of cables for as many as sixty cable cars traveling up and down Broadway from the Battery to Midtown.

The frame of the building is made of steel and iron with a terra cotta and stone facade. By 1901, the last steam powered cable car made its journey down Broadway and the line became electrified. By 1904 the advent of the subway made cable cars completely obsolete. The building was used for garment industry manufacturing until being turned into retail and office space in the 1980s. Today the bottom levels are occupied by a Crate & Barrel store on the Broadway side and the Angelika Film Center on Houston.

White designed mansions for most wealthy prominent New Yorkers of the Gilded Age, including the Goelet family. The Goelets were originally hardware merchants and in the late 1800s brothers Robert and Ogden started building real estate. In 1886 they commissioned the firm of McKim, Mead and White to design the Goelet Building.

The structure is seemingly sleek compared to some of White’s other more ornate designs. Constructed in the Chicago School style, the facade is a mix of different shades of brick and cream colored terra cotta arranged in sawtooth, basket weave, and linear patterns. The structure rises ten stories high. After the death of the Goelet brothers, their heirs sold the building to a developer who made some renovations and continued to use it as a commercial space. By the 1970s the building and the surrounding area had become dilapidated. The structure was purchased by real estate investor Zoltan Justin who, with the help of his son Jeffery, undertook a major restoration project that cleaned the facade, removed roll-down gates that covered the rounded corner storefront, took out cinderblock infill from between the arches and completely redid the lobby.

This current co-op building was once the private residence of James Hampden Robb, a former New York Senator and Commissioner of the Parks Department. The Robb house is one of the earliest Renaissance Revival styled townhouses White designed. The facade boasts Roman iron-spot brick and a base of brownstone with tan

brick and terra-cotta ornaments. Architectural critic Russell Sturgis described the now landmarked the house as “the most dignified structure in all that quarter of the town, not a palace, but the fit dwelling house for a first-rate citizen.”

After serving as the Robbs’ residence, the Murray Hill building was acquired in 1923 by the Advertising Club which used is as its headquarters until 1977.

White designed these six neo-Italian Renaissance townhouses for Henry Villard, a journalist, financier and early president of the Northern Pacific Railway. The brownstone structures are arranged into one U-shaped unit surrounding a courtyard originally planned as a turn-around for carriages. This landmarked “House of Mansions” has a stately and dignified appearance based on sixteenth century palaces.

The Villard Houses remained private residences until the 1970s when the wings were taken over for non-profit use. In 1981 the central structure became the Helmsley Palace Hotel, a luxury hotel. After more changes in ownership and a multi-million dollar restoration, the building is now the city’s largest luxury hotel, the Lotte New York Palace.

In 1903 then president of Tiffany and Company Charles T. Cook reportedly asked the firm of McKim, Mead and White to “build [him] a palace.” The interpretation of that request was 401 Fifth Avenue, a seven story white marble structure based on the sixteenth-century Palazzo Grimani in Venice. The building appears to only have three stories thanks to the three horizontal divisions that frame rows of two story windows Corinthian columns.

Tiffany and Company’s move from Union Square to this spot on Fifth Avenue and 37th street helped establish Fifth Avenue as one of the most prestigious and sophisticated shopping thoroughfares. 401 Fifth was given landmark designation in the 1980s and Tiffany’s moved its headquarters further up Fifth Avenue.

In 1852, after being denied admittance to the Union Club, a group of six German New Yorkers created their own social club. Originally named “Gesellschaft,” now known as the Harmonie Club, this society is the second oldest social club in New York City and is made up of men and women who are prominent leaders in the worlds of business and finance, law, science, medicine, arts, and all walks of life. Stanford White designed their second clubhouse which the club moved into in 1905.

The Beaux Arts structure designed by White once had a basement bowling alley and bedrooms on the upper floors that are no longer there. The club retains the original dining room designed by Stanford White, as well as other impressive Club facilities.

Image via Wikimedia Commons, NYPL Digital Gallery

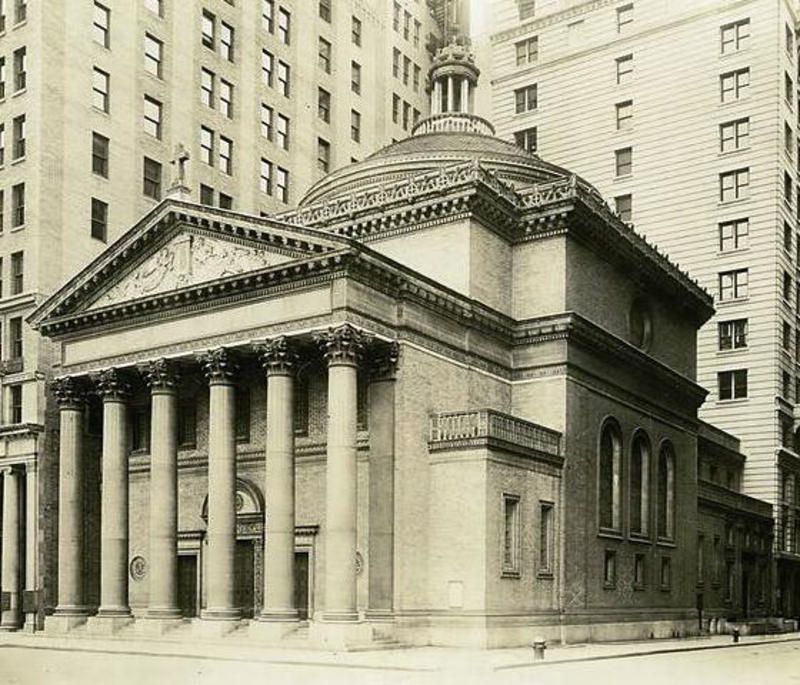

Madison Presbyterian Church was a very short lived stay on 24th Street. Built in 1906, the Palladian structure was demolished only thirteen years later in 1919 to make way for insurance offices. Despite the church’s early demise, many of its ornamental features were salvaged and made their way into homes and museums around the country.

According to the New York Times, a doorway from Madison Square turned up in storage at the Brooklyn Museum, the church’s Tiffany windows with biblical scenes now illuminate a wedding chapel at a hotel in Riverside, California, and the building’s stone columns and some terra-cotta flourishes were transferred to a former newspaper headquarters in Hartford.

Stanford White designed the permanent clubhouse of the Century Association in 1889, three years after he was elected as a member to the club and forty-two years after the club was established. The Italian Renaissance structure is made of granite, terra-cotta and brick. The club has a striking front facade with a monumental arched entrance doorway underneath a Palladian window centered between four handsomely wreathed round windows.

The Century Association was established in 1847 to promote the advancement of art and literature. Its name is due to the fact that the membership was originally limited to one hundred people. The association moved around to different downtown rentals for decades until moving into the White designed clubhouse.

Now home to the Cultural Services of the French Embassy, 972 Fifth Avenue was designed by Stanford White as a mansion for Payne Whitney, a financier and philanthropist who was well-known for his racing and breeding stables on Long Island and Kentucky. Whitney’s wife lived in the house after his death until she too passed away in 1944. The building was purchased by the Republic of France in 1952.

The mansion was designed in the style of the high Italian Renaissance with a curved light gray granite front and pitched tile roof with a deep overhanging stone cornice. In 1970, the five story structure was designated as a landmark and recognized as “one of the last reminders of the Age of Elegance and “an integral part of the last complete block of impressive town houses remaining on the Avenue.”

The Henry Cook Mansion is often though to be a part of the Payne Whitney House, since they are adjacent structures that have very similar styled, but they are in fact two separate residences. Henry Cook, a banker and railroad tycoon, commissioned White to build him a townhouse on the illustrious Fifth Avenue. White designed an Italian Renaissance Palazzo style home with more than 15,000 square feet of living space, but neither her nor Cook would live to see it complete. A year after Cook died, leaving the unfinished home to his daughters, White was murdered on the roof of Madison Square Garden. The townhouse was complete in 1907.

The property caused a stir when it was put up for sale in 2009 for a whopping $49 million and eventually sold for $42 million. The residence faces Central Park and has retained many of its original features, including moldings, fireplaces, leaded-glass windows, and the original floor plan.

During the Revolutionary War, 11,500 American prisoners of war died in captivity aboard sixteen British prison ships in New York Harbor. The bodies were originally buried by Brooklyn residents in shallow graves in what is now the Brooklyn Navy Yard. But through erosion, bones began to emerge on the shoreline by 1808. The Tammany Society made the first motion that year to find a formal burial ground for the prison ship martyrs, a quest joined by Brooklyn citizens over the next few decades. The remains were re-interred in Fort Greene Park under a small monument that was replaced in 1908 by a 149-foot column designed by Stanford White. The single Doric column, known now as the Prison ship Martyrs Monument, is topped with an eight-ton bronze funeral urn by sculptor Adolf Weinman.

Next, check out 6 Lost Mansions of the Upper West Side and Upper Manhattan

Subscribe to our newsletter