New Book Reveals the Frick Collection's Luxurious Interiors

See the stunningly restored rooms of a former Gilded Age tycoon's mansion, now home to one of NYC's most illustrious art museums!

In the last two decades, the Brooklyn neighborhood of Gowanus has undergone a striking evolution. The industrial fabric along the Gowanus Canal, the polluted Superfund site, has become increasingly juxtaposed with high-rise luxury residential buildings and trendy food, drink and retail businesses. Because this is New York City, this type of urban transformation has come to feel seemingly inevitable. But a group of Gowanus residents and organizations such as the Park Slope Civic Council and Historic Districts Council, has come together to form The Gowanus Landmarking Coalition, which recently launched its new website.

The mission of The Gowanus Landmarking Coalition is to advocate for the landmarking of important historical, architectural and cultural sites in Gowanus, before neighborhood rezoning takes place and to ensure that the neighborhood retains its rich industrial aesthetic, which draws from its lively history as a vital hub for manufacturing and shipping. A public meeting regarding the rezoning plan took place on February 6th, and the clock is now ticking to make sure that no more iconic sights get lost to future demolitions, like the Burns Brothers Coal Pockets building did in 2014.

The Gowanus Landmarking Coalition urges community residents to sign the petition found on its website, in order to protect the neighborhood’s built environment from the City Planning Commission’s rezoning plans. As Kelly Carroll of the Historic Districts Council says, “Gowanus should not be left with a paltry three or four designated landmarks when the rezoning dust settles. Telling the full story of this neighborhood’s industrial and maritime heritage requires more than a dozen sites. Our Coalition priority list is a good start.”

Untapped Cities has worked with the Gowanus Landmarking Coalition to share 10 of the 15 buildings the Coalition is highlighting on its new website, all of which the Coalition believe warrant official designation by the City of New York. Read on to see what’s at stake:

Less than a block away from the Gowanus Canal, 450-460 Union Street (a.k.a. The Green Building) is an example of the rich industrial history hidden in the neighborhood. Originally the home of the bass foundry Thomas Paulson & Son, The Green Building first began to operate in the 1860s, after the Civil War, and tells the story of Gowanus’ beginnings as a center for manufacturing and shipping.

The Green Building is also an example of an un-landmarked building being saved by the community. In 2002, in the hopes of constructing a luxury residential tower in its place, plans were made to demolish the site, but thanks to pushback from devoted residents, the building was not granted a residential rezoning.

Picture courtesy of The Gowanus Landmarking Coalition

The Green Building is now used as an event space. The building features 6,000 square feet that openly and proudly display the building’s industrial past, with exposed brick walls, open-beamed ceilings and open-air courtyard that allows the sun to shine through floor-to-ceiling glass doors.

Picture courtesy of The Gowanus Landmarking Coalition

Thomas Roulston’s story is one of those self-made success stories that are an integral part of New York City’s inspiring history. Roulston’s father was an Irish immigrant who started out as a grocery clerk in Brooklyn, but he eventually became the grocery’s owner. Thomas Roulston went on to lengthen his father’s legacy, and by 1888 Roulston owned three grocery stores and bought the 70-124 9th Street lot in order to construct a grocery warehouse. This warehouse was the center storage for what became the Roulston Company, which owned over 300 stores spanning across the five city boroughs.

The Roulston Buildings, just a few blocks off of the Gowanus expressway, are examples of Renaissance Revival architecture, with their corbeled cornices and segmentally arched windows.

Picture courtesy of The Gowanus Landmarking Coalition

The Gowanus area became a center for industrial construction and activity thanks in large part to the Gowanus Canal. Previously a creek, this canal was created in the 1860s and quickly made Gowanus an important cargo transportation hub, the surge in the canal’s use running parallel with the predominance of waterborne shipping.

James A. Dykeman chose to buy the lots on Union Street for his box factory because, among other things, the lots backed onto the canal, making it easy and cheap to receive shipments of materials, as well ship products. The National Packing Box plant knew enough success to grow from one building to a five-building complex, and 543 Union Street is still used today to house an array of small businesses and art studios. You may be familiar with the interior of this building as the former location of Proteus Gowanus and the original location of the Morbid Anatomy Library.

Picture courtesy of The Gowanus Landmarking Coalition

Located at the end of the Gowanus Canal, the Gowanus Flushing Tunnel, now more than 100 years old, was originally used to flush the canal’s dirty water, polluted by household waste and industrial toxins, out from the canal and into the Buttermilk Channel. By 1999, however, the strategy for cleaning Gowanus canal was flipped; the tunnel now pumps water from the East River and Buttermilk Channel into the canal, “flushing” the canal with clean water.

Most of the original brick tunnel is still intact today, with a recent restoration which can be seen along the sides of the canal, and the exterior of the pump house remains largely the same, despite removal and reconstruction of much of the pumping house’s equipment during the 1990s. The brick walls and design of the building’s roof showcase the popular industrial architecture of the early 1900s.

Known by many as “The Bat Cave”, this massive 8-story building overlooking the canal was once a powerhouse for the equally massive Brooklyn Rapid Transit (BRT), and during the 1900s the building burned coal in order to supply electricity to the steam railroads, elevated railroads and streetcars of Brooklyn. During the early 2000s, the abandoned building became home to a community of squatters and acquired its name, “Bat Cave”. The original Romanesque Revival design of the building can still be seen in its red brick and bluestone trimmings.

Fortunately, this site is not at risk of demolition or long-term neglect anymore. The site was acquired in 2012 by the Powerhouse Environmental Arts Foundation, a nonprofit which plans to adaptively reuse the building as an art and arts fabrication center. The project is designed by architects Herzog & de Meuron, scheduled to open in 2020.

Picture courtesy of The Gowanus Landmarking Coalition

With its granite horse trough standing in front (long ago filled in) and a carving over the doorway, the ASPCA Memorial Building tells the story of The American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty of Animals, the oldest animal protection society in the Western Hemisphere. Originally focused on protecting horses from abuse, the ASPCA used to be located in a basement at 114 Lawrence Street, but Brooklynite philanthropists helped move the ASPCA to the building now standing on Butler St, between Bond and Nevins. You can actually enter it because there is a hidden music shop, Retrofret, in the back, well worth a visit.

The ASPCA Memorial Building was designed, in 1913, by the architectural firm Renwick, Aspinwall & Tucker. Successor to one of the most influential architects of the 19th century, James Renwick Jr., the firm is known for having designed some of Manhattan’s most famous skyscrapers, like the landmarked American Express Building at 65 Broadway.

Picture courtesy of The Gowanus Landmarking Coalition

Built on the Fourth Street Basin of the Gowanus Canal, “The Can” began as canning factory that, within its first year, was producing 1,800 tin boxes a week. Bought in 1901 by the American Can Factory, the complex is 130,000 square feet and holds 6 buildings, a medieval-esque courtyard and long, narrow alleyways.

The Can was developed and is now operated by XO Projects Inc., and it is still a center for production today. The building is now home to a wide array of artists and an even wider array of exhibitions and performances. During the summer, Rooftop Films uses the building’s spacious rooftop for their film festivals.

Picture courtesy of The Gowanus Landmarking Coalition

The lots on the corner of Butler and Nevins were purchased around 1900 by Robert Graham Dun, owner of the firm R.G. Dun and Company, originally known as The Mercantile Agency. Dun hired Moyer Engineering and Construction in 1914 to build a four-story, fireproof building for his printing company. What resulted was a 100 x 200 square-foot, concrete-reinforced masonry building, with terra cotta partitions, cement-finished floors and a tar and gravel roof. The building is in the style of industrial art deco and uses blue terra cotta detailing to delicately offset the gray concrete of its structure.

In the 1960s the building briefly became the home of a plastic manufacturing company before remaining vacant for several years, and it has recently become zoned for residential use.

Picture courtesy of The Gowanus Landmarking Coalition

In the span of thirty years, starting around 1850, more than 300 storehouses were built along Brooklyn’s shores. The S.W. Bowne Grain Storehouse, between Bay and Creamer Street, is one of the final remnants of the industrial popularity of the Red Hook Gowanus waterfront.

The S.W. Bowne Company sold hay, straw, grain and feed, and their Brooklyn storehouse held the company’s bulk raw material. Despite its traditional red brick structure, the storehouse actually has a unique architecture, with its gable-ended design and clerestory windows on the upper roof section, allowing light to shine into the warehouse (something rare for warehouses at the time).

On June 14, 2018, shortly after Gowanus residents called to landmark the building, a suspicious fire ran through the storehouse. Fortunately, the building still retains much of its architectural integrity.

Picture courtesy of The Gowanus Landmarking Coalition

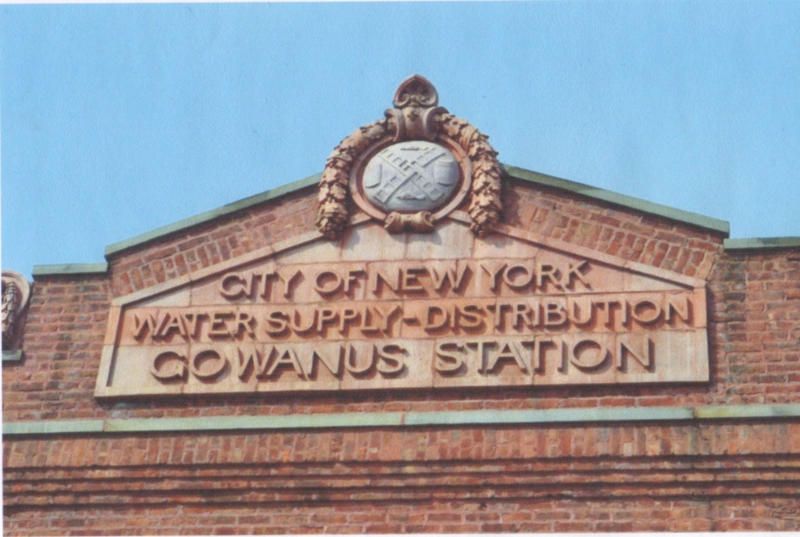

Constructed in 1914, the Gowanus Station is an example of Beaux Arts architecture and covers two whole city blocks. The two-story brick building holds many architectural and design gems, such as a lovely pediment of terra cotta detailing, bluestone water tables and decorative scrollwork over its window openings. A site so beloved by the neighborhood residents, the Gowanus Station has even been the cause of a candlelight vigil, the community’s reaction to its impending destruction.

The New York City Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) has proposed new tank sight design that would destroy the station, and has not shown any change in the design that would retain the building or any of its façades, despite public outcry and calls for a new design that incorporates the east and north façade.

Sign the petition on the Gowanus Landmarking Commission website to show your support for these and other buildings at risk.

Next, check out the Top 12 Secrets of the Gowanus Canal.

Subscribe to our newsletter