♀️ The Trailblazing Women of Wall Street

Women have long shaped Wall Street—even when history tried to write them out.

This year marks the 40th anniversary of Battery Park City, one of New York City’s first built-from-scratch neighborhoods. Constructed on landfill at the southern end of Manhattan, Battery Park City is a unique development of residences, retail, public parks and waterfront. Untapped Cities Insiders recently spent an evening traversing the neighborhood with the urban designer who created it’s master plan back in 1979, Brian Shea of Cooper Robertson.

Throughout his career Shea has been instrumental in the development of various innovative urban design plans and has helped shaped cities across the country. After interning with the Boston Redevelopment Authority, Shea made his way to New York City for graduate school at Columbia University. From there he became the first employee of Cooper Roberson and has been with the firm ever since. We sat down with Shea before our Insiders tour, in front of Stuyvesant High School at the northern end of Battery Park City, to learn more about his work and his take on urban design in New York City for our latest NYC Makers profile.

Brian Shea: The forest in Prospect Park in Brooklyn. It’s where you can be in the middle of nature but also in the middle of 2.8 million people.

Brian Shea: Every time Hudson Yards changes. Hopefully the northern end of the High Line as it meets the convention center. The new work out on Roosevelt Island for Cornell University. Let’s see…

Brian Shea: Well, I always love Jacob Riis Park. It’s where you can actually get to the ocean in New York City. My alma mater Columbia University, I haven’t really walked around a lot where they’ve been expanding, just to see how it looks, how it’s doing. And the ever evolving Brooklyn riverfront, DUMBO, now it’s climbing up towards the Navy Yard.

Nicole Saraniero, Untapped Cities: What makes New York City great to you?

Brian Shea: Well, A, its diversity, B, its size, C, its very complicated relationship with water. It’s unlike other cities, say in Australia, like Melbourne, Sydney, or Brisbane. They have one big idea about the water. Sydney is this big harbor, Melbourne is this enormous bay on the south ocean, and Brisbane is about a river. New York has lots of water and lots of different waterfronts and because of that it has this incredible physical diversity. I can’t really think of another city, you can think of Stockholm maybe, that’s as impressive in that way.

Brian Shea: Right, and when you look at the bridges, just the positioning of the bridges, you can see how it literally sets the plan, the street and block plan, of like half of Brooklyn. Just because of where the bridges are located, how they are angled, where they go. The canal becomes Flatbush and takes you out to the ocean. It’s amazing.

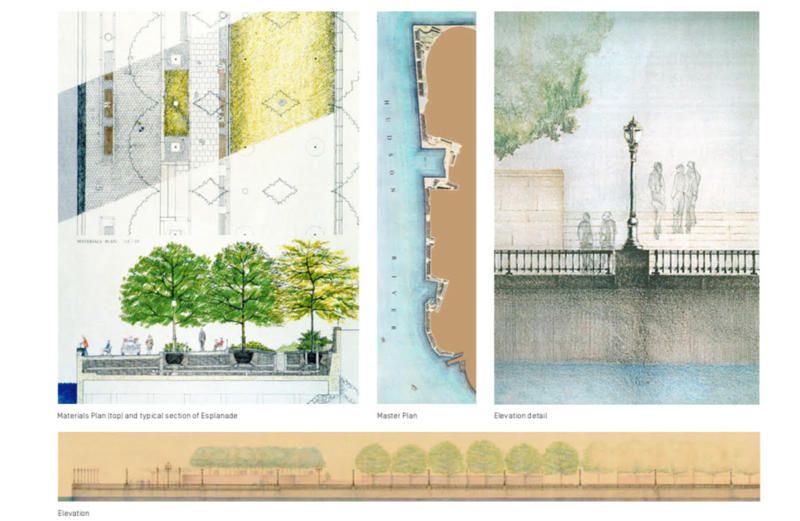

Shea on our Insiders tour explaining the unique curved design of the waterfront fences on the Battery Park City esplanade that allow for an unobstructed view of the waterfront while seated

Shea on our Insiders tour explaining the unique curved design of the waterfront fences on the Battery Park City esplanade that allow for an unobstructed view of the waterfront while seated

Brian Shea: A lot of oversized infrastructure on the waterfront makes it difficult to get to it. They’ve been eliminating a lot lately. With that there’s going to be better ways to address flooding in the future other than a six foot concrete wall, which wouldn’t be pleasant for anybody.

Anything to improve the environment of the subway, ways down to it, and once you’re down there, what it’s like on the platforms. Other cities have done a great job with integrating development or just penetrating active sunlight down into a subway. Also connections with other modes of transportation, that’s not so easy in New York. If I have to take a bus in from New Jersey, then what do I do? Or how do I get to the airport if I don’t have a car and I don’t want a $75 taxi ride? Infrastructure needs a lot of work I think, public transit.

I would also say New York City tends to be pretty conservative with its development practices and its building types. If you go to other cities they are much more innovative with the kinds of housing they build, how they are going to develop density but still in a low rise configuration, how they’ll mix different uses in one building. It’s very rare in New York to find an office building with housing on top of it, but it’s state of the art in Chicago for example. We tend to be quite conservative in how we build. That’s because we are developer driven, unfortunately.

Brian Shea: Battery Park City is one. There are many players in Battery Park City but I was fortunate enough to be a master planner and designer from the beginning, working with Stan and Alex and others. It’s one of the highlights of my work in New York City.

Another one was doing a framework plan for the entire Yale University and trying to get the Yale office to think about Yale physically, rather than academically or programmatically, but not give them a traditional master plan. They wanted a framework plan which they could use to inform future designs. It was really great to evolve a product that wasn’t a traditional master plan but was more in terms of framework which has helped us since with other schools.

Let’s see. Stapleton. Denver had an old airport, Stapleton Airport, which was one quarter of their city in land area. It was seven and a half square miles. When they opened the new airport further east in the prairie, all of a sudden the city of Denver could fill up the hole. It was very interesting to work on the conversion of a commercial aviation facility, to see the completion of an evolving 20th century city and see where the city meets the prairie. Very cool. That was a big one. It turned into all kinds of neighborhoods, public parks. We took the old east-west runway and it became one of the major new avenues in Denver. There were challenges like, if they were to blast the concrete of the airport runways, it would be the largest quarry in the rocky mountain region. So we tried to figure out what to do with all the concrete. We also designed the first prairie park in the midwest United States, we daylighted a lake once the runways were gone and reconnected it to the Platte River. It was a huge project that tried to balance nature, with urban development and a way of creating a place for work and residents. It’s still under construction and we finished the plan in 2001, 2002.

Stapleton Airport Redevelopment Plan – Urban design and development plan for the nation’s unprecedented closure and conversion of a 5,000-acre, international airport to non-aviation use. Courtesy of Cooper Robertson

Brian Shea: One unique problem was governance because, Battery Park City Authority was not a city agency. It could override anything in the city if it wanted to but it had to work with the city. It was trying to blend a new kind of design guidelines that could also be adopted by the city instead of traditional zoning. You also had three different heads of the Battery Park City Authority over time and they each had their own particular point of view.

In terms of infrastructure, it was extremely challenging. Any waterfront, derelict waterfront or landfill, from an infrastructure point of view, is really difficult. Everything at Battery Park City is on fill, so everything has to be carefully considered in terms of loading. All of the utilities for example are on piles. Every tree on the esplanade is in a tree pit on a pile above the river. The seawall had its challenges, not to mention that the PATH tubes of New Jersey come right through the commercial center. The original World Trade Center, all its air conditioning intake, everything came in from the river, so there were tunnels everywhere.

I would say the most challenging part was to make it familiar to New Yorkers. It was abandoned as a beach for twelve years. The landfill was here but it was fenced off and inaccessible. So what do you do? There was an existing plan in place but it was so complicated that no one could figure out how to build it and no developer would touch it. Then the bonds were coming due which funded the original landfill and they had to be paid back. There was nothing in place to pay them back with. We were given ninety days to come up with a new plan so we could start this thing. Doing a master plan in ninety days was challenging.

Brian Shea: Yea, and this was before the age of the computer! Everything was ink on mylar, hand drawn.

Brian Shea: We did it.

Plans for Battery Park City, Courtesy Cooper Robertson

Brian Shea: Hudson Yards. The new subway line under 7th avenue and the extension of the subway to Hudson Yards. The Brooklyn waterfront, Roosevelt Island, the southern end being developed by universities. Columbia’s new work. The new residential development around the High Line is pretty cool because it’s the first time we’ve done something other than conservative development and building types. The new buildings are pretty cool.

Brian Shea: They are not afraid to try new construction techniques, materials, form and shape. It’s quite different than what you see here [at Battery Park City]. These are all LEED rated buildings, but it’s still your standard brick and stone construction. The High Line is something different.

Brian Shea: We have a big mixed-use project that is still in the planning process in New Jersey. A new way of thinking about retail and a retail shopping street. Rather than a conventional mall, it’s integrated with office development and residential. That’s being done by a developer out of Atlanta and who has tried it in Atlanta and has been quite successful.

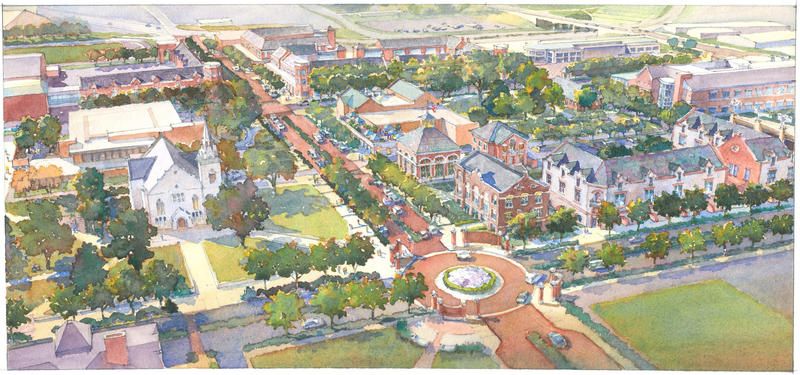

I’ve been working on a master plan for Georgia State University, which is in downtown Atlanta, and it’s now the largest university in the state of Georgia. It is trying to, on its own, be a catalyst for the development of downtown, to reactivate downtown Atlanta, and that’s pretty cool. The third one, I do a lot of campus designs, so we’ve just been finishing, two plans, one is for Longwood University in Virginia, part of the University of Virginia system, and a small but really innovative school called Drury University in Springfield, Missouri. Totally wants to reinvent itself, physically, academically, it’s pretty neat what they are trying to do. That’s about it.

Plan for Drury University, The Master Plan accommodated future growth within the existing campus while also strengthening the fabric of the campus with the new Student Life Center and residential quad as the core of the campus. Courtesy of Cooper Robertson

Brian Shea: If you are going to be an urban designer, you have to tolerate the fact that urban design is an anonymous art and in the end you’re not going to be remembered for the plan, it’s going to be the architects who build the buildings that get remembered. So don’t feel frustrated. It’s not a profession for the ego-minded, urban design. Architecture is a different story.

I would say in this world today, rather than take on the money maker projects and the name recognition projects, you should be contributing a lot of time to solving third world problems and social problems in an innovative physical way. There’s just too much that needs to be done that can’t be ignored, no matter what profession you go into.

Brian Shea: Well my other life is a musician, so right now I am reading a philosophical and musical analysis of Wagner’s Ring Cycle. At the same time, attending the Ring Cycle and getting it into my head musically. I revisit it once every five or six years. The Met put on a great production of it this year, very innovative set. So that’s my other life.

Brian Shea: I play classical piano and I’m a composition amateur. I do that along with, sometimes more often than, architecture practice.

Brian Shea: I’ve had my works performed. I’m just too chicken to perform them. Most of my work is too hard for me to perform.

Brian Shea: Piano since I was about six and I’m now 68. After completing what I thought was a pretty good life in the architecture profession I went back to music school and spent three years in Paris in composition school in the summers.

Brian Shea: Other than I’m a composer?

Nicole Saraniero, Untapped Cities: We could use that!

Brian Shea: I’m also trained in the Hudson River School of landscape painting which is a very specific way of painting and creating colors from oil paint. You are only allowed to use certain colors and you have to make your own green. That’s cool. I’m a grandfather with Australian grandkids, and I’m also a farmer on the side. We have a farm in upstate New York.

Brian Shea: We are very close to Olana. We go there maybe once every two weeks for a walk. Depending on the weather, if we want to catch a sunset we just drive up and go. I do a lot of pro-bono work with Scenic Hudson. One project I’m really proud of, up the river from the Palisades, across from the Cloisters museum, it’s sort of a national historic view, just north of the George Washington Bridge. LG was going to build this disgusting ten, twelve story glass corporate office tower. Scenic Hudson came to me and said, “Can we do anything to combat what they are about to do?” And I said, “Sure.” So I took their square foot program and I researched historically that traditional Korean architecture is all based on courtyards, so I said, let’s do a courtyard corporate office complex and not go above the tree line. So then you wouldn’t see it. You wouldn’t see it from the river or from the Cloisters. So I had to present it to LG and they came back with, “We can’t do that. It’s not in our corporate culture,” blah blah blah. Then we worked with Scenic Hudson, at that time Lawrence Rockefeller was on the board, and a year later they come back and say, “We are going to build a three story courtyard scheme,” which is now under construction. We saved the view. That was all pro-bono work. That’s what I mean about doing work that has some public benefit.

Brian Shea: That was my other pro-bono work for Scenic Hudson. I was asked to help develop the pedestrian connection between Thomas Cole’s house and Olana. I did these conceptual sketches and one of them I did was this pedestrian link and this new traffic rotary and open space design in the foot of the bridge. I didn’t present it but the head of the bridge authority presented it to Cuomo and he said, “I want to do this.” So he gave $10 million. The rotary is done, landscape is done. It used to be this ugly highway interchange on the ground and no one knew what lane to go in or where to turn and it took up a lot of space. So it’s all gone and now you can walk, there’s a cantilever walkway on the south side of the bridge, there’s bump outs for people to paint, and we’re going to put up correspondence between Cole and Church along the walk, then integrate in the carriage trails that take you up to Olana.

Check more NYC Makers profiles here!

Subscribe to our newsletter