After-Hours Tour of "Noguchi's New York" Exhibit

Join an exclusive curator-led tour at NYC's Noguchi Museum!

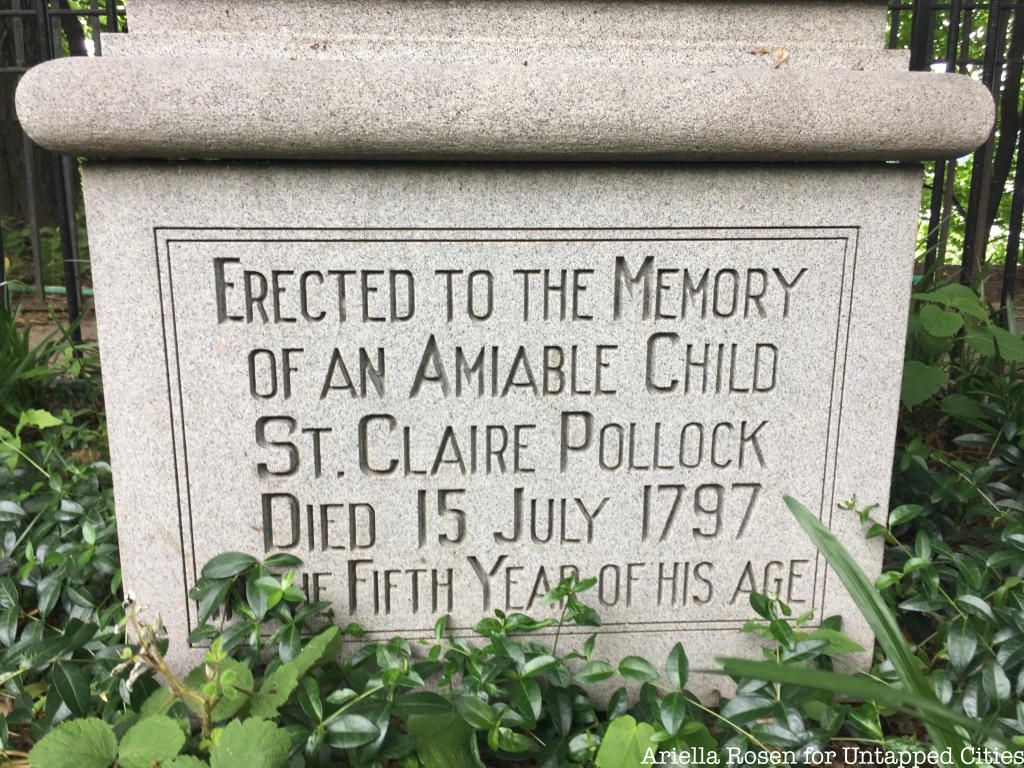

In the shadow of Grant’s Tomb in Riverside Park, there is a much smaller monument which has puzzled historians and passers by alike for over 200 years. Approximately 100 yards north of the great mausoleum stands the tomb of the “Amiable Child.” The modest granite urn and pedestal (a replica of the original white marble) mark the final resting place of a four-year-old boy, St. Claire Pollock, who died in 1797. The inscription on its base reads:

Erected to the Memory

of an Amiable Child

St. Claire Pollock

Died 15 July 1797

In the Fifth Year of his Age

Beyond what is written on the tomb, very little is known for certain. However, people have long been drawn to the unassuming little grave. An article in The New York Times from 1895 points out that this only served to heighten the curiosity about the monument.

The story goes that young St. Claire had been playing near his family’s house on the rocky bluffs that lined the Hudson River, when he lost his footing and fell to his death. The next day, one of the family’s servants found his body where it had washed up onto the rocks. Rather than bury the child at Trinity Church, the Pollocks chose to make his grave high up on Strawberry Hill (now Claremont), overlooking the water, in the place where the boy had been playing just before he died. This is alleged to have been his favorite spot.

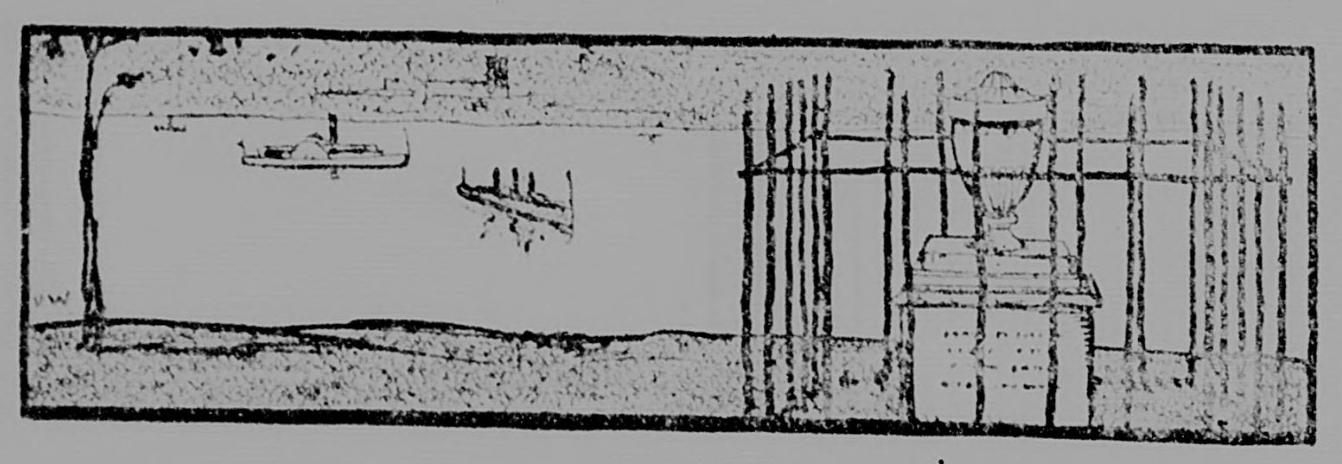

A sketch of the Amiable Child Monument that appeared in the New York Tribune on September 14, 1919.

At the time of the burial, the property belonged to George Pollock, an Irish linen merchant who is generally thought to be either St. Claire’s father or his uncle. In 1800, however, economic losses forced Pollock to sell his land to his neighbor, Cornelia Verplanck, and he left the tomb of the “amiable child,” with its iron enclosure and marble monument in her care. Remarkably, the grave went undisturbed, even though the property changed hands many times before it was bought by the city in 1873 and turned into Riverside Park.

The “amiable child” monument was brought into the public eye around 1897, when Grant’s body was transferred to the newly constructed mausoleum in Riverside Park. As people visited the grave of the civil war hero, they were moved to discover the solitary plot of the little boy. The humble grave captured the hearts of those who came to gaze on the grand mausoleum, and many set out to learn who this St. Claire Pollock was. Newspapers of the day––the Times, the Sun, the Tribune––received numerous letters to the editor from curious locals and amateur historians. During the summer of 1900, the New York Times ran at least one article on the subject every month, each one telling a slightly different story.

allegedly

fell to his death exactly one century prior. Image from Library of Congress.There is no evidence to suggest that the boy ever actually fell off the cliff, but this is the most common narrative and the one told by both the Riverside Conservancy and the New York City Parks Department. In another popular version, St. Claire drowns while on a fishing expedition with his father. These stories, which live at the intersection of folklore, memory, and urban legend, have taken on a life of their own. According to an article in The New-York Tribune from 1919, St. Claire Pollock was a cautionary tale that mothers would use to frighten their children into obedience.

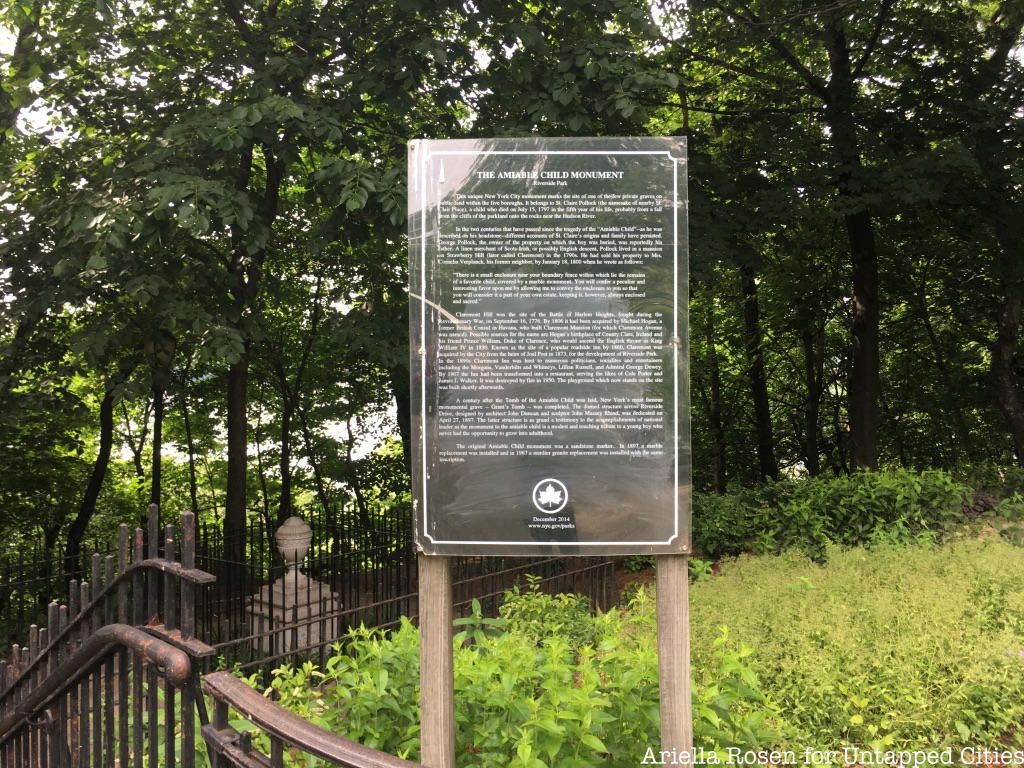

A sign from the NYC Parks Department, telling the history of the monument and its location.

A sign from the NYC Parks Department, telling the history of the monument and its location.

Like an unknown soldier, the “amiable child” seemed to represent all lost children, if not the country itself. Some emphasized boy’s likely connection to Oliver Pollock, who played an important role in the American Revolution. Others traced his ancestry back through generations of proud warriors to William St. Claire, who fought beside William the Conqueror, but later came to reveal the imperialist tendencies of his kinsman. In his proximity to Grant, many even came to associate the boy with the Civil War and left flowers on his grave on Decoration Day.

The once-desolate landscape where the boy was buried has changed a lot since 1797, when the country was still young. Riverside Park––and New York City as a whole––have grown up around his little grave, serving as a reminder of the distant past, as well as of the ever-changing present.

Next, check out 14 of NYC’s Smallest Cemeteries, By Number of Interments and The Top 10 Secrets of Riverside Park in NYC.

Subscribe to our newsletter