How to Make a Subway Map with John Tauranac

Hear from an author and map designer who has been creating maps of the NYC subway, officially and unofficially, for over forty years!

Courtesy of Williams New York

It’s hard to imagine today that people had to be lured to settle on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, but such was the case at the turn of the 20th century when the first New York City subway line opened. The Interborough Rapid Transit Line (IRT) started at City Hall, with the most epic of subway stations (now closed off to the public except on official Transit Museum tours). The Astors and other enterprising investors owned the land uptown, purchased in a speculative property boom. Now, the question was how to brand the area. No longer just for bachelors, apartment living was made luxurious and drew wealthy New York families out of their single family homes downtown and into apartments uptown. This change in not only location but also in lifestyle was often a hard sell, so the apartments had to be decked out in the latest modern amenities and features that single family homes couldn’t offer. The speculative investments paid off and many luxurious apartments of the Pre-War era are still some of the most coveted New York City addresses. Check out some of the oldest and most luxurious apartments and hotels of the Upper West Side:

Popular legend has it that The Dakota was so named because when it was built it was so far north it might as well have been like living in the Dakotas. Another theory is that Edward Clark, the building developer and former president of the Singer Sewing Machine company, chose the name because of his penchant for the Western states.

The Dakota was designed by architect Henry Janeway Hardenbergh, who also designed the Plaza Hotel. After four years of construction and going doubly over budget with a cost of more than $24 million dollars in today’s money, the Dakota welcomed tenants into its 54 suites in 1884. The units were designed for families and all told there were 500 rooms within the building. The Dakota was the first apartment building to make the Upper West Side, and apartment living, desirable. The Dakota still functions as a luxury apartment building and remains one of the most sought addresses in the city, with former residents famously including John Lennon and Yoko Ono as well as Lauren Bacall, Judy Garland and many prominent New York City figures.

Courtesy of Williams New York

On his deathbed, the patriarch of the Astor family, John Jacob Astor reportedly said “Could I begin life again, knowing what I know now, I would buy every foot of land on the island of Manhattan.” The scope of the Astors‘ real estate empire stretches from Queens to Harlem and many vestiges remain to this day including such famous buildings as the Waldorf-Astoria, Astor Place, the Public Theater (which was originally the Astor Library), and the Upper West Side apartment building, The Astor.

The apartments at 235 West 75th Street were among the first in the area. Built by William Waldorf Astor in 1901, the original two-towered, grey brick structure crowned by an elaborate decorative cornice was designed by architects Clinton and Russell. A third tower in the same style was added in 1914 with a matching design by the architecture firm of Peabody, Wilson and Brown.

The large penthouse-style apartments attracted wealthy businessmen who were drawn to the Upper West Side thanks to its close proximity to Central Park, the first subway line, and the bustling thoroughfare of Broadway. After the glory days of the Gilded Age, the building fell on hard times in the mid-twentieth century and was converted into a single-room-occupancy building.

The Astor Lobby, Photograph by Evan Joseph

Original Marble and mosaic tile details in the lobby

Today, The Astor has undergone an extensive renovation and redesign to bring back the splendor of the Gilded Age. Inside there are 98 new units designed by the illustrative firm of Pembrooke & Ives. While the units bare little resemblance to the originals of the early twentieth century, the lobby and exterior facade maintain many of their original historic features. On a recent tour of the building with Untapped Cities Insiders, we got a first hand look at the lobby’s marble fireplaces, benches and elegantly curved staircases as well as the intricate mosaic tile floors and restored decorative molding. The building retains much of its old world charm with added modern amenities like twenty-four-hour concierge, a gym and state-of-the-art interior enhancements.

Just south of 72nd Street is The Dorilton, a striking French-inspired apartment building noted for its extreme three-story extension of the mansard roof and a monumental archway high up in the sky. It was built between 1900 and 1902 of limestone and brick, with an iron gateway that once served as a carriage entrance

Architectural historian Andrew Dolkart has called The Dorilton the “most flamboyant apartment house in New York” while the Landmarks Preservation designation gives more reserved praise, as “one of the finest Beaux-Arts buildings in Manhattan.” On a fun note, the Dorilton has been a popular apartment for artists and musicians due to its large rooms and soundproof construction.

The Hotel Belleclaire, one of the first of the luxury hotels of the Upper West Side, was also a first for renowned architect Emery Roth. After this first major commission, Roth would go on to design many other distinctive apartment buildings in the area like the two-towered San Remo, Eldorado and Beresford. Like the Ansonia, the Belleclaire was labeled was an apartment hotel, a multi-dwelling property which catered to wealthy families who were used to having a house staff. The Belleclaire had ground floor restaurants and offered room service, as well as full service staff members who were at the disposal of residents. Another amenity offered to the residents of the Belleclaire was a basement bowling alley, which unfortunately was turned into storage.

The design of the Belleclaire is intentionally unique. While other apartment buildings going up at the time took cues from European styles, namely the Beaux-Art style, Roth based his design on elements of the Art Nouveau movement of France and Belgium and the Secessionism of Austria and Germany. The result is an elegant red brick building with limestone, terra-cotta and metal ornamentation. There used to be a domed cupola at the top of the building, though it has yet to be replaced.

Like many luxury apartments which flourished in the early 20th-century, The Belleclaire was deeply affected by the Great Depression. By the time of the 1939 World’s Fair, the hotel had lost many of its permanent residents and was advertised as a transient hotel in a brochure advertising a nightly rate of just $2.50 for a double room. Famous figures such as Maxim Gorky, Mark Twain and Babe Ruth have stayed there. Though there are still a few permanent residents today, the building has undergone an extensive restoration and now operates as a boutique hotel.

Exterior of The Chatsworth, Courtesy of March Made

Standing stately at 344 West 72nd Street at the base of Riverside Park, The Chatsworth is a landmarked Beaux-Arts apartment building completed in 1904. Designed by architect John E. Scharsmith, the building originally contained sixty-six “housekeeping apartments” which ranged in size from five rooms to fifteen rooms. It included all of the modern amenities of the time like a conservatory in the mansard story, a sun parlor, billiard parlor, a cafe, a first class barbershop, ladies hair dressing parlor, a valet and tailor service, not to mention amazing views of the park and the Hudson River.

Today those sixty-six units have been replaced by fifty-eight co-op units, also designed by the firm of Pembrooke & Ives. Just as in its early days, The Chatsworth continues to offer residents the best of modern amenities including a library, media screening room, wine tasting room and an outdoor garden. The interiors retain the elegance of the building’s exterior Gilded Age opulence with historic hand-carved walnut paneling, ornate plaster ceilings, and white-oak herringbone floors in the lobby, enhanced by revitalized skylights and new modern light fixtures. On a recent tour of The Chatsworth Untapped Cities Insiders got to see how the old world has blended with the new in these historic buildings, and of course enjoyed the views over Riverside Park.

The Ansonia Hotel went up even before the opening of the subway, from 1899 to 1904. Developer William Earl Dodge Stokes was the so-called “black sheep” of his family–one of nine children born to copper heiress Caroline Phelps and banker James Stocks. Stokes predicted that Broadway would one day surpass the renown of Fifth Avenue to become the most important boulevard in New York City, the city’s Champs-Élysées. The Ansonia Hotel would herald these changing times, located in a prime location on 73rd Street just one block north of the subway station.

One thing to keep in mind is that the term hotel in the time period of the Ansonia meant a residential hotel, more like if you combined today’s luxury apartments with a full-service concierge and housekeeping staff. The French-inspired building, with its mansard roof, contained 1,400 rooms and 230 suites across 550,000 square feet. Pneumatic tubes in the walls delivered messages between staff and residents. A wonderful spiral grand staircase of marble and mahogany led up to a skylight seventeen floors up. At maximum capacity, the ballrooms and dining rooms could accommodate 1,300 guests.

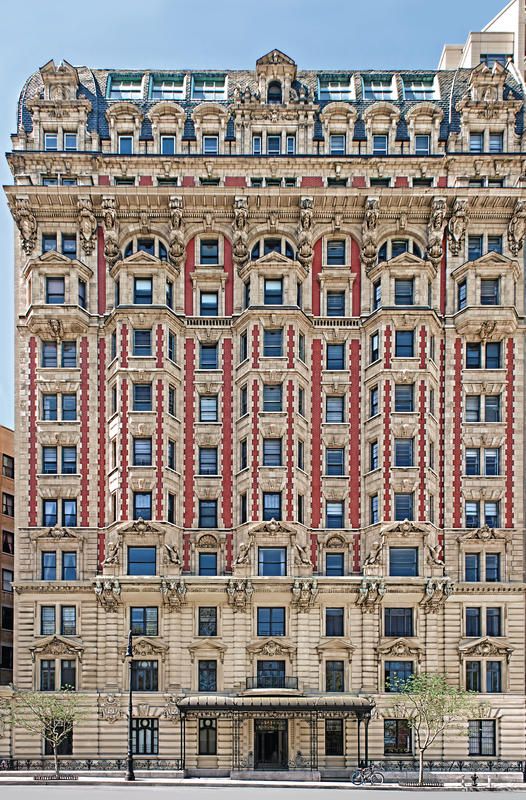

Designed by Harry B. Mulliken of the firm Mulliken & Moeller, The Hotel Lucerne stands out due to its bold color and grandiose Beaux-Art style. Throughout the day, the building appears to change color, thanks to a purplish hue that Mulliken added to the red bricks and terra-cotta that the facade is made out of.

The Hotel Lucerne opened in 1904 as a resident hotel where there was a mix of permanent families and transient guests. Today, the building operates solely as a hotel in the modern sense of the word and is undergoing a multi-million dollar renovation. When Untapped Cities recently walked by, the entire building was covered in scaffolding.

The main draw of The Prasada apartments at 50 Central Park West was a luxury that remains hard to come by in New York City apartments, and that is space. Each of the floors in the 12-story Beaux-Arts style building contained only three apartments, ensuring that each resident would have large rooms to move around in. There was an eight room apartment in the rear and two larger ten room apartments to the front.

Starting with a redesign in 1919 which broke up the large apartments into smaller units, The Prasada has seen many changes over the decades. The 1919 redesign replaced the original two-story mansard roof with a flat brick facade. It also connected every apartment to a large, staffed kitchen by electric dumbwaiter. The Prasada was converted to a cooperative building in 1988 and underwent another redesign in 1999 by architects Ehrenkrantz Eckstut and Kuhn.

For those that wanted a more private living style and garden space, The Astors had an ingenious architectural solution. Take a palazzo-style building and carve the inside out, leaving garden space in the courtyard. The result was the uniquely designed Apthorp. Though the courtyard took up valuable square-footage, it allowed more sunlight and fresh air to reach the existing apartments.

Built between 1906 and 1908, the 12-story luxury apartment building takes up an entire block. Over the years, it has been home to many celebrities including Cyndi Lauper, Rosie O’Donnell, Robert DeNiro and Nora Ephron (who wrote about her love for the Italian-Renaissance styled building in the New Yorker). While many development projects undertaken by the Astors bear the family name, such as the Waldorf-Astoria and Astor Court, this project is named after the owner of the former Apthorp mansion, merchant and Royalist Charles Ward Apthorp. Apthorp’s mansion demolished in 1891 to make way for the extension of 91st street.

Often overshadowed by the neighboring Dakota and San Remo apartments, The Kenilworth, built in 1908 and designed by the firm of Townsend, Steinle and Haskell, was the last of the Second Empire style buildings to pop-up along Central Park West. Now a designated landmark, the building at 151 Central Park West stands only 12-stories tall, due to contemporary residential building restrictions and its lack of a steel frame, but its elaborate ornamentation and mansard roof make it appear much taller.

To this day the building’s exterior red brick and limestone facade, with a grand entrance sporting two-story columns, has maintained its grandeur. The interior layout has remained largely unchanged as well. As when it was built, each floor is divided into only three separate apartments with seven to nine rooms each.

The Belnord is another Astor development and like The Apthorp, it has arch entrances and a central courtyard. Proportionally, it may not be the more pleasing of the two but it has a distinctive architectural element that sets it apart. While at first glance it looks fairly uniform, upon closer inspection you can see that the rows of windows contain windows of varying size, shape and decoration.

The courtyard also sets the Belnord apart. Including the Apthorp, the Belnord and Graham Court (next slide), there are very few courtyards in New York City large enough for a car to enter and make a complete turn around. Due to it’s distinct architectural features and historical significance, The Belnord, which was completed in 1909 and designed by architect H. Hobart Weekes, was designated a landmark in 1966.

Back in the day, the Astors were also interested in Harlem and built the 800-room Graham Court starting in 1898. It was for whites only and did not integrate until sometime between 1928 and 1933—one of the last buildings in Harlem to do so. Once that took place, important African American community leaders moved in.

Graham Court was the first courtyard building constructed by the Astors in 1901. It was designed like and Italian Renaissance palazzo by the same architecture firm as The Astor apartments on 75th Street, Clinton & Russell. Spanning the full length of 7th Avenue from 116th to 117th Streets, the impressive building has appeared in many films such as Spike Lee’s Jungle Fever and the television series, Mozart in the Jungle.

This post was written by Michelle Young and Nicole Saraniero

Subscribe to our newsletter