Lost Gilded Age Mansions are Rebuilt with Plants at NYBG Holiday Train Show®

The demolished Clark and Vanderbilt mansions are among a handful of lost NYC buildings resurrected at this festive holiday display!

Henry Clay Frick’s house, designed and built between 1912 and 1914, stands majestically on Fifth Avenue.

“The Met is admired, but the Frick is beloved,” says architecture critic Paul Goldberger, comparing New York City’s largest and wealthiest museum with its reserved Fifth Avenue neighbor a few blocks to the south. The Frick Collection bestows the extraordinary benefit of letting patrons sit and contemplate Henry Clay Frick’s legendary collection of old masters in his serene mansion—all the big names are here—at least until the museum closes for an extensive renovation in 2020. And what a museum it is! It also recently had a starring role in the HBO Max television show The Undoing.

Frick furnished his 61-room house with Rococo and Renaissance furniture, and accumulated superb decorative arts, including Limoges enamels, Meissen porcelain, and Italian bronzes. His architect, Thomas Hastings of Carrère and Hastings, embellished the rooms with carvings of ancient symbolism, including acanthus leaves indicating long life (which Frick did not obtain) and laurel representing victory (which was often his). Frick’s instruction to Hastings had been to build him “a small house with plenty of light and air,” one that would be “simple, in good taste, and not ostentatious.” Architectural critic Dino Marcantonio calls the house a work of art in its own right, worthy of its own visit.

Whatever Frick’s hopes for simplicity, the house is one of palatial grandeur, says Metropolitan Museum Director Emeritus Philippe de Montebello. It pulls you in a magical way out of the din of the daily life of New York into its formal intimacy and serenity. There’s no other remotely comparable museum in New York, or perhaps anywhere else on the planet. When it opened in 1915 Architecture Magazine called it the most costly and sumptuous house in America.

Yet The Frick’s serenity today belies a history of labor violence, corporate contention, bitter family disputes, and even a Rasputin-like attempted assassination of Henry Clay Frick himself. The late 19th century’s Gilded Age had produced unprecedented wealth for a few legendary corporate titans who worked together and knew one another well. Of the immense fortunes of Morgan, Mellon, Rockefeller, and Carnegie, Frick’s was second only to Rockefeller’s, calculates Forbes. Or, as his biographer Samuel A. Schreiner summarizes, the span of Frick’s adult years “corresponded almost exactly with that of the fantastic period of explosive growth in material wealth that made the United States the richest, most powerful nation on earth.”

The Frick is the vision of this one man, says Xavier F. Salomon, Chief Curator of The Frick Collection, noting that a Frick picture is calm and elegant, a thing of extreme beauty. To understand the vision we must consider the man whose life, thoughts, and experiences led him to this collection. What kind of man would leave us this extraordinary legacy? His $117 million bequest to the public (roughly $2.3 billion today) was the largest in American history, and a story, according to PBS‘s Treasures of New York, of remarkable wealth and unprecedented generosity. What’s more, Frick in his will stipulated that “the entire public should forever have access” to the art, an astonishingly liberal concept for the day.

Yet in his Diary of an Art Dealer, René Gimpel vividly describes conversations with Frick in which “his cold eyes, grasping and hard under their genial look, remain a clear, beautiful blue.” And the obits written at his death were far from kind. The New York Tribune, for example, claimed that “The name of Frick is abhorrent to great numbers of his fellow citizens.” By most accounts, said the late Christopher Gray, architectural columnist for the New York Times, Frick was the “meanest, richest, striking-breakingest steel man you would ever want to meet,” a ruthless businessman who nonetheless developed a refined taste in art and who was devoted to music.

During his recent 2019 Frick exhibit, artist and author Edmund de Waal confronted the matter directly: Who is Henry Clay Frick becoming as he put together the collection? Who is this oligarchical American collector-industrialist hoping to be? De Waal thinks he sought to emulate and become part of a European aristocratic tradition. And that may be. But isn’t it equally possible that as he left behind the viciousness, brutality, and ugly, coke-induced pollution of Pittsburgh, he was seeking a life of equanimity in New York, as he withdrew from corporate battles and spent his evenings contemplating his paintings?

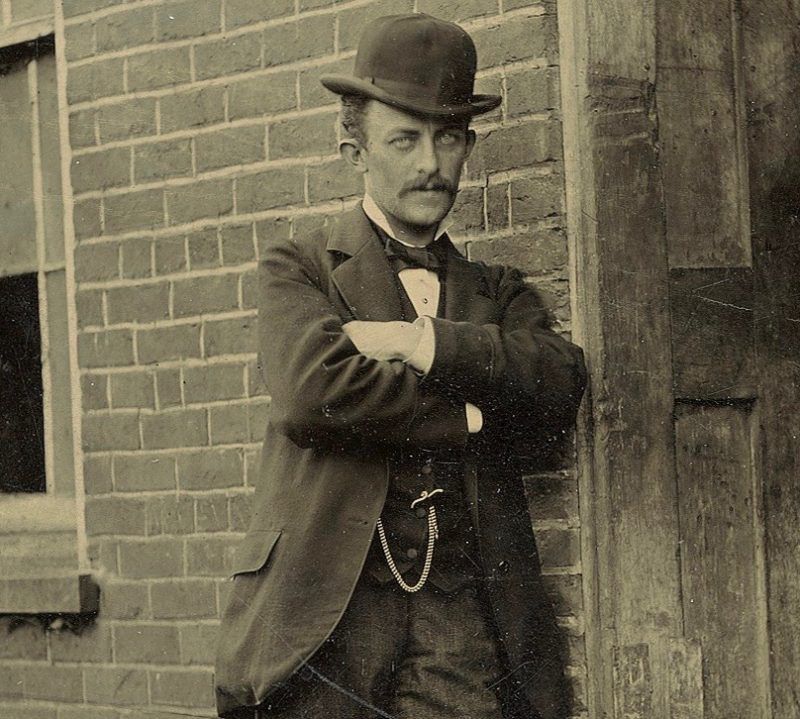

Henry Clay Frick, age 26, about to embark on the mining career that would make him King of Coke (roughly 80% of the steel industry bought Frick coke). Courtesy of The Frick Collection/Frick Art Reference Library Archives

Or so said the radical anarchist, Andrew Berkman, who shot him. An implacable opponent of labor unions, Frick provoked a major strike at Carnegie Steel’s Homestead plant in June 1892 by cutting wages in the fearsome mills. When the powerful Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers objected, Frick locked out the workers and called in 300 Pinkertons. He surrounded the mill with a 12-foot-tall fence topped with 18 inches of barbed wire and searchlights on the corner towers. It was promptly called Fort Frick. Nonetheless, the Pinkertons were “outnumbered, outgunned, and trapped” in a humiliating defeat, according to the Homestead Foundation. They were captured and forced to run a gauntlet of furious workers and sympathizers before being packed into trains and sent out of town to safety. After the governor of Pennsylvania summoned the National Guard, not really fair play, Frick hired replacement workers. In Homestead’s many violent clashes, hundreds were injured and some 16 people were killed. Public opinion turned decisively against Frick.

Then, in a disastrous blow to the labor movement, Andrew Berkman, long-time lover of Emma Goldman (they were called anarchism’s royal couple), arrived in Homestead. Planning to commit an attentat, or act of political assassination to remove a tyrant, he burst into Frick’s office and fired point blank, hitting Frick in the left earlobe. The bullet penetrated his neck and lodged in his back. Hurled off his feet, Frick was struck by a second bullet to the neck. A Frick worker grabbed Berkman’s arm, forestalling a third shot. Badly wounded, Frick nonetheless tackled Berkman, who stabbed Frick four times before he was brought down by a carpenter wielding a hammer.

When Berkman was searched by the police he was found to have a dynamite capsule in his mouth and one in his pocket. He explained at his trial (where he was found guilty and sentenced to 22 years in prison), “My act was to free the earth of the oppressors of the workingmen.” Instead, his act set back the labor movement decades, until the New Deal, as public opinion shifted again.

Another serious black mark against Frick was the earlier, horrific Johnstown Flood in 1889 in which some 2,200 people drowned. Caused in large part by the neglectful practices of the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club, of which Frick was a leading member, the flood was ruled an act of God by the courts, but not by history.

Berkman and Frick remained oddly linked. Berkman and Emma Goldman were awaiting deportation in Chicago when they heard the news of Frick’s death on Dec. 2, 1919. “Deported by God,” said Goldman. “Well anyhow, he left the country before I did,” said Berkman. He and Goldman were deported later that day.

The Richard Morris Hunt Memorial funded by the Art Society (now the Municipal Art Society), on the eastern edge of Central Park, faces the Frick Mansion.

Even in 1906, Henry Clay Frick’s real estate transaction was extraordinary: He bought the only full block front on Fifth Avenue, a lot 200 feet wide by 175 feet deep, and slightly raised over the rest of the neighborhood. He intended that his new house would best his rivals, including Carnegie and Vanderbilt, but to do so he first had to destroy a landmark. Not a problem.

Built in 1877 and demolished by Frick in 1912, the Lenox Library was both an architectural landmark and an intellectual one. Funded by wealthy philanthropist James Lenox, it was one of the first libraries in New York to be open to the public. Lenox hired eminent architect Richard Morris Hunt (1827-1895) to build his Neo-Gothic palace of rare prints, maps, manuscripts, and books, including a Gutenberg Bible. Ironically, Lenox’s taste was similar to Frick’s and his library housed paintings much like those later prized by Frick. Lenox bought, for example, the first two J. M. W. Turner paintings in the United States. His estate, which fell into financial disarray after his death, sold both Turners. Frick went on to buy Turners of his own, including the Harbor of Dieppe of 1825 and Cologne, The Arrival of a Packet-Boat: Evening of 1826.

Meanwhile, as New York’s most famous architect, Hunt had been honored in 1898 with a Fifth Avenue memorial designed by Bruce Price with sculptures by Daniel Chester French, sited directly across from where the Lenox Library once stood. If the Hunt memorial serves as a perpetual reprimand for the annihilation of a lost masterpiece, Henry Clay Frick apparently didn’t care.

@Michael Bodycomb, Courtesy of The Frick Collection

Frick’s fortune was based on innovative steel manufacturing techniques and an early prescience of the coming importance of coke, an industry that he dominated quickly and ruthlessly. He appreciated new technology in business and at home. Taking a cue from his most fashionable contemporaries who had bowling alleys, Frick commissioned a stylish subterranean bowling alley in 1916, along with a billiards table for playing billiards or pool.

Bowling had historically been partly a game of strength when the balls were made of lignum vitae, a very hard wood. But in 1905, the first rubber ball was invented, followed in 1914 by the Brunswick Corporation’s Mineralite ball, made of a “mysterious rubber compound.” Rubber balls modified the game, as did the Frick’s revolutionary ball return technology that relied on physics and gravity, and allowed players to gracefully remain where they were, rather than chasing the balls up and down the lanes. Often confused for the bowling alley in the Greystone Mansion in Beverly Hills, where There Will Be Blood was shot, the bowling alley at The Frick does feature a similar return mechanism.

Though the rubber ball helped make bowling popular with women, daughter Helen Clay Frick was not a fan. When she founded her Frick Art Reference Library, she commandeered the basement space for her books and files. Later, one of the wood-paneled walls of the bowling alley would be moved to the new Frick Art Reference Library space.

Courtesy of The Frick Collection/Frick Art Reference Library Archives

Nonetheless, in 1997 the Frick undertook a meticulous restoration of the bowling alley and billiards room, although both are now generally closed to the public due to the difficulties of access down several flights to the basement and the fact that it has only one method of egress.

Elaborate mechanized musical devices were all the rage among the swells of the early 20th century. Andrew Carnegie urged his friend Frick to buy an orchestrion—a gigantic self-playing instrument that imitates orchestral sounds much like a player piano—which he did for his Pittsburgh house, Clayton. But in New York he opted for a different instrument, an Aeolian Organ, to be fitted into an arched niche at the foot of the main staircase, letting music be heard at dinner in the dining room. The staircase’s ornate wrought-iron balustrade was inspired, appropriately, by the dean’s staircase, designed by Jean Tijou, at St. Paul’s Cathedral in London. The placement in the staircase, alas, muted the resonant sounds the organ should have produced. Frick had engineers try to reconfigure it, but unsuccessfully.

In his biography of Joseph Duveen, S. N. Behrman had written that it was Frick’s custom to have an organist in on Saturday afternoons to fill the gallery “with the majestic strains of ‘The Rosary’ and ‘Silver Threads among the Gold’ while he sat on a Renaissance throne. He must have felt that only time separated him from the Medicis, claimed Behrman.

The country’s most successful early 20th century model, Audrey Marie Munson, posed for the Frick pediment, which was sculpted by Sherry Edmundson Fry and carved into stone by Attilio Piccirilli. Said to have a perfect form, Munson was known as American Venus, Miss Manhattan, and the Panama-Pacific Girl. She is the golden woman protecting the Maine monument on Columbus Circle, fertile Pomona at Grand Army Plaza, Beauty at the New York Public Library, Civic Fame topping the Manhattan Municipal Building, and the spirit of commerce on the approach to the Manhattan Bridge. She is both of the “two colossal figures by Daniel Chester French that welcome me at the Brooklyn Museum every day,” says Anne Pasternak, museum director, in James Bone’s biography of Munson, The Curse of Beauty (replicas were placed at Manhattan Bridge in 2017 for a Percent for Art installation that is still in place).

Munson came to a sad end after a failed silent film career (she was the first American actress to appear nude) and a spectacular scandal involving a former lover who had murdered his wife to marry her. Committed to a psychiatric institution at age 40 by her mother, she spent the rest of her life institutionalized until she died in 1996. Contemporary artists and researchers are working to re-examine and publicize Munson’s life and achievements in The Audrey Munson Project.

Munson was not the only star involved in the pediment, which was carved by Attilio Piccirilli of the extraordinary Piccirilli Brothers firm. Sons of a master Italian carver of marble, the Piccirillis had come to New York from Tuscany in 1888, bringing with them an “artistry and passion for stone-carving unrivaled in the United States.” From their studio in the Bronx, they produced many of America’s most celebrated monuments, including the Lincoln Memorial on Washington D.C.‘s Mall. Only the best was good enough for Frick.

Portraits of Sir Thomas More and Thomas Crowell on opposite sides of the mantel, as Frick had hung them

Frick’s friend, the painter Charles Ricketts, summarized the scene in 1919: “Imagine Sir Thomas More, the beautiful saint, and [Thomas] Cromwell, the monster, united in history, art, and tragedy, now facing each other, united by Holbein and time and chance.” In recent years novelist Hilary Mantel has upended the reputations of the two men, depicting More as a sort of monster and Cromwell as a sainted bureaucrat. She deals directly with the evidence of Holbein’s unattractive portrait of her hero Cromwell by having him say, “I look like a murderer,” to which his son replies, “Didn’t you know?” The two portraits stand as one form of evidence for today’s viewers to make up their minds about saint and monster. Mantel aside, Holbein’s More is considered the superior painting of the two, probably the greatest Holbein in America, says Salomon.

Bellini’s St. Francis in Ecstasy

Director Ian Wardropper points out that Frick hung the Living Hall with portraits of “principled men,” such as St. Jerome and Sir Thomas More, as well as Giovanni Bellini’s “St. Francis in Ecstasy,” facing St. Jerome opposite. The Frick Collection has retained this format in part out of deference to Frick himself but also, Wardropper told Hyperallergic, “because it’s really hard to beat the hang that he did. The pendant of two Holbein paintings, the way the Middle Eastern carpet is harmonious with Chinese vases — it’s such a perfect impression of his taste that we leave it that way.” Very few American collectors of the early 20th century were interested in Spanish paintings or in El Greco, says Wardropper, which makes Henry Clay Frick ahead of his time in yet another way.

Because of the frequency with which they must replace the carpet, The Frick believes St. Francis to be their most viewed painting. There is similar evidence, says Wardropper, that it was Frick’s most viewed painting as well. While Frick bought relatively few religious paintings, the portrait of St. Francis is simultaneously a mystical painting and a superb landscape. Bellini’s plants, for example, are so detailed and accurately drawn that modern botanists can identify nearly all of them, however obscure.

Ironically, Frick initially disliked Bellini’s St. Francis, and arranged to return it to M. Knoedler’s Gallery. A horrified Sir Joseph Duveen, a rival dealer who was with Frick on 70th Street at the time, persuaded him that St. Francis was the pinnacle of the Italian Renaissance. Frick kept it, and grew to cherish it.

John Russell Pope’s Garden Court for the Frick heralded his similar courts in the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC.

Classicist John Russell Pope, the architect chosen to convert the house to a museum, was one of the most distinguished architects of the early 20th century. Yet he was reviled on his death and criticized in the harshest possible terms for decades. His design, for example, for the Jefferson Memorial (equally beloved today) was called a servile sham, decadent stylism, and, grimly, a cadaver. He was even contemptuously called the last of the Romans, intended as a profound insult. But who doesn’t admire Rome today? Indeed, when in 2001 Princeton architect Michael Graves received the highest honor of the American Institute of Architects, the Gold Medal, he was asked to name the five best buildings in the world. His first choice: Rome, in its entirety. Paul Goldberger says that Pope used classicism as a source of dignity, distilling it down to its essence, which is precisely what Frick wanted.

Frick was ahead of his time in leaving a substantial endowment to be used for ongoing maintenance. He had once asked derisively about his former colleague, Andrew Carnegie, “What’s the point in Carnegie’s giving libraries to all those towns that go busted trying to keep ’em up?” He wasn’t about to make the same mistake.

The Landmarks Preservation Commission gave the Frick Collection permission in 1983 to jackhammer the gorgeous bluestone sidewalk that Frick himself had ordered installed in 1914. The large flags were traded for smaller Canadian granite stones that would be ”easier to maintain,” said the museum. But by 2000, the easier-to-maintain stones were cracking and had to be replaced, having lasted 17 years to Frick’s 70 years of perfection. Earlier, in 1973, The Frick’s acting director promised the Landmarks Commission that it would not pursue demolishing a townhouse it owned at 5 East 70th Street, but then did so anyway, wrote Christopher Gray. It then proceeded to build the Page garden on this site, a tactic that produced all sorts of grief when the Frick hoped to demolish the garden, as it had demolished the townhouse.

The Russell Page Garden in its spring serenity

But when it decided in 2013 that the easiest way to obtain much-needed space would be to build a 60,000-square-foot addition in the Page-designed garden, it didn’t anticipate the uproar that followed from preservationists, landscape architects, the media, and immediate neighbors on the Upper East Side. How important is the garden? Charles Birnbaum, president of the Washington-based Cultural Landscape Foundation, called Page’s design a “master class in restrained minimalism” that is a model of precision and beauty, giving an illusion of size to a postage-stamp sized garden.

Model of the renovation coming designed by Annabelle Selldorf

Facing defeat, The Frick gracefully withdrew its unloved plan and proposed a more modest expansion by Selldorf Architects, which proposed an idea from 1932: convert the second-floor residential rooms to public and gallery use. The area beneath the garden, long a storage space, will be turned into a 222-seat auditorium. This plan, despite some serious opposition, made its way through the politically charged land-use-review process that includes input from the local community board and approval from the Landmarks Preservation Commission. The plan now faces review by the Board of Standards and Appeals.

The second floor of the Frick Collection, which will be opened to the public in the new renovation

There’s little question of The Frick’s need for a comprehensive renovation, which hasn’t been done for more than 80 years. Its electrical system hasn’t been updated since 1935, and it is pretty much inaccessible to any visitor in a wheelchair. While refreshing the major galleries, the Selldorf plan leaves them much as they are now, while upgrading amenities, providing unprecedented public access to the original residence on the second floor, and upgrading The Frick’s infrastructure.

Or so wrote historian Hilary Ballon in her monograph, Mr. Frick’s Palace. Far from being the conservative and staid mansion many of us see, The Frick is subversive, “purposively estranged from the urban form of Fifth Avenue.” This is a “New York monument that opposes New York,” she writes. Defying the street wall as well as real estate principles of maximum land use, the house is set back 75 feet from Fifth Avenue, “a dramatic departure from that basic precept of New York urbanism, the street wall.” On 71st Street the house has a blind wall with very little relief beyond the corner.

Ballon summarizes that the architect was “able to express potentially conflicting qualifies of grandeur, amplitude, and openness, especially on the outside, and intimacy, domesticity, and comfort within.” In her view the mansion is less New York than Paris, where Hastings was educated in 1880-83. A lifetime Francophile, Hastings designed the mansion as a 17th-century classical hôtel organized around two sequential spaces, a courtyard and a garden on a long rectangular lot. And even though the front garden is a private space belonging to Frick, its exposure on Fifth Avenue had the opposite effect. “The garden was the very public face of the palace,” writes Ballon, “which was an utterly un-New York solution.” And since there’s nothing else remotely like The Frick in New York, one pretty much has to agree.

A portrait of Frick’s wife, Adelaide, sits on the desk in the Fragonard Room

Adelaide Frick sprained her ankle in Italy in 1912, causing her husband to cancel their trip home on the Titanic. Had they perished on that disastrous voyage, we wouldn’t have any of The Frick Collection today.

He was an attentive, affectionate family man, so much so that in Henry Clay Frick: An Intimate Portrait his great-granddaughter Martha Frick Symington Sanger argues convincingly that family memories and tragedies, including the death of two children, influenced his choice of paintings. The young girl holding a doll in Renoir’s Mother and Children, for example, looks much like his late daughter Martha, who died at age six.

Building on Sanger’s argument but drawing different conclusions we might ask if Frick’s acquisition of violent industrial paintings, such as Francisco de Goya’s The Forge, did not reflect his ongoing obsession with the physically powerful men in Pittsburgh who had faced the terrible fires of his coke ovens, his protagonists who produced his inestimable wealth?

Like many another native New Yorker, Stan Lee, founder of Marvel Comics, walked by the Frick Mansion as a youngster, peering through the magnificent iron fence to the fantasy palace beyond. Little wonder then but he decided that the Frick was the proper mansion for his Stark Family Manor. Sticking close to the Frick facts, Lee says the manor was built in 1932 by industrialist Howard Stark. And just as he believed that New York was the proper location for superheroes and villains, he concluded Fifth Avenue was their natural neighborhood. As co-creator of The Avengers, Lee modeled the Beaux-Arts Stark Family Manor on the Beaux-Arts Frick Mansion and located it at 890 Fifth Avenue, a sort of zoning joke for the Frick’s location at 1 East 70th Street. Today, of course, Fifth Avenue addresses are more prestigious than side street addresses, and would be the preferred address of an eminent family like the Starks.

The original Stark Family Manor was close to its iron gate on Fifth Avenue. But to give the manor the privacy superheroes needed to carry out their business, Thor and Iron Man pushed the mansion back and up to its current location a year after the Avengers moved in. The manor had nine bedrooms and bathrooms, its own Quinjet hangar, a swimming pool, an underground gym and training facility, and numerous labs. Also a billiards table much like Frick’s.

Celebrated New York Times photographer Bill Cunningham loved the Frick, and photographed it often. The spring after he died, the magnolia trees failed to bloom for the first time in their history, recalls Heidi Rosenau, The Frick’s Associate Director of Media Relations & Marketing.

While the Fifth Avenue Garden as a whole had been designed in the early 1930s by Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., son of Central Park‘s planner, the three magnolia trees were planted later, in 1939. The two trees on the lower tier are Saucer Magnolias (Magnolia soulangeana) while the tree on the upper tier adjacent to the flagpole is a Star Magnolia (Magnolia stellata). They are pruned yearly to maintain their generous shape in proportion to the block-long limestone facade. Bill Cunningham loved them, and they apparently loved Bill Cunningham.

Photograph by Lucas Chilczuk, Courtesy of the Frick Collection, A First Friday evening with Vermeer’s Mistress and Maid

“I should think you might secure better prices,” Henry Clay Frick chided his prominent interior decorator, Elsie De Wolfe. “Take your time! You know time is money.” In the spirit of their founder, The Frick offers bargains, including lower prices at designated times as well as gratis sketching materials.

On the first Friday of every month, except September and January, museum admission and gallery programs are free in the evening from 6 PM to 9 PM. Visitors have access to the permanent collection and special exhibition galleries, as well as talks and lectures by curators and music and dance performances. Open sketching, with complimentary materials including paper, white and black pastel pencils, and eraser provided by The Frick, can be done in the Garden Court. You can sit on the steps around the fountain or use a fold-up chair. Chamber musicians often play in the evening.

Regular paid admission ($22, adults; $17, seniors and visitors with disabilities; $12 students) includes superb audio tours, which may be the finest in New York. You and three friends can schedule a private tour (two-week advance notice required) for $200, which includes admission, making the tour itself nicely priced. You can also take advantage of the return of the Connoisseur Pass, which gives you access to The Frick Collection, Neue Gallerie and the Morgan Library & Museum for $45, which can be purchased on the Frick Collection website.

You can pay what you wish on Wednesdays from 2 PM to 6 PM, when the museum closes. Wednesdays, which had been slow, says Heidi Rosenau, are “now our boom time of the week.” Free lectures on every conceivable subject of interest to Frick patrons are live-streamed most of the time, so long as the speaker is willing. The lectures, ordered chronologically, are then made available on the Frick site as well as SoundCloud and iPhone‘s app store.

Membership is rewarding. For $75 a basic membership gets you admission (no waiting in line), and gives you an additional ticket for a friend on Member Mornings, when you are allowed a private viewing of the current exhibitions. Plus you get a 10% discount at the museum shop. There are also Member Preview Days and Afternoon Talks for Friends. And you receive the beautifully produced and printed Members’ Magazine, the summer issue featuring Tiepolo in Milan, which closed in July.

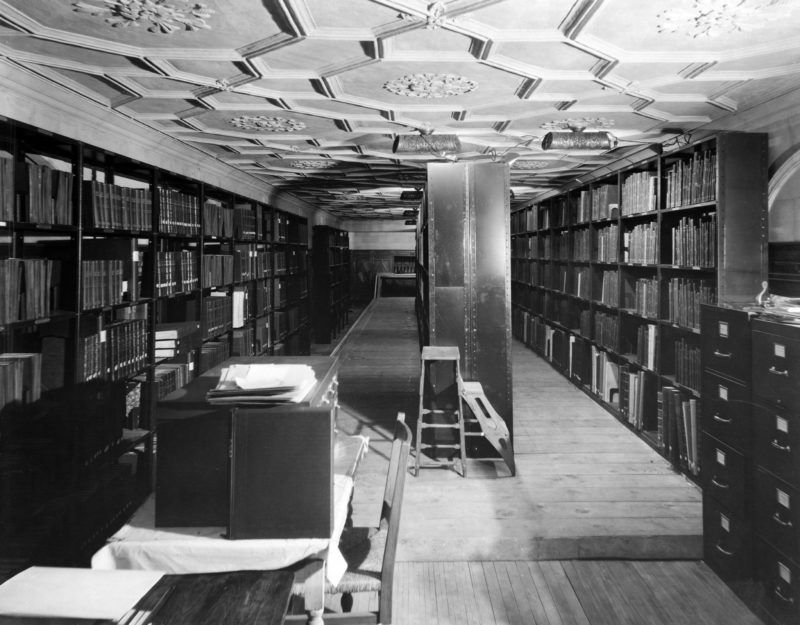

Photograph by Michael Bodycomb, Courtesy of the Frick Collection, Frick Art Reference Library reading room, where mapping occurred to help the allies preserve cultural treasures in Europe during World War II.

Between the 13th and the 16th of August 1943, 65% of Milan’s historic monuments were severely damaged or demolished by Allied bombing, said Xavier Salomon in presenting Tiepolo’s lost frescoes, all of which were obliterated. The Frick’s spring 2019 exhibition was designed to bring back to life these extraordinary frescoes through reconstruction, using all the known drawings, three oil sketches, and black-and-white photographs done between 1897 and the 1930s, before the bombing. Only the oil sketches give a sense of the incredible color range used by Tiepolo. The Palazzo Archinto, entirely destroyed, held one of the great libraries as well as extensive art, decorative objects, and mosaics. At the time of the bombing, the Italian army had been destroyed and Mussolini forced to step down. Almost no military historian regards the bombing as militarily necessary or even productive. At the press preview, Salomon pointed out the destruction occurring today in Iran and Iraq.

Saving antiquities started with daughter Helen Clay Frick (1888–1984), whose “passionate and persistent efforts” in preserving and documenting art, wrote Schreiner, “made to wash the blood of Homestead from her father’s image.” If so, her achievements were impressive. A serious art historian, she recognized the importance of having good images to study art, and founded the Frick Art Reference Library to collect and document art. In part she was motivated by her experience first in World War I but later World War II, when so many works of art were lost. Regarded as one of the world’s finest libraries the Art Reference Library has a collection of some 228,000 titles and 3,300 periodicals, as well as hundreds of thousands of photographs and images. The Selldorf plan will, for the first time, provide direct access to the reference library from The Frick.

The Met Breuer, soon to be the temporary home of the Frick Collection

We’re about to find out. While its mansion is being renovated, The Frick Collection will move uptown for a two-year sabbatical in the Met Breuer, formerly the Whitney Museum. And how will the paintings do on the Breuer’s austere white walls?

Putting a resolutely cheerful face on the coming trauma, Frick Collection director Ian Wardropper says, optimistically, that the move may be a good time for experimentation and trying new things. “The experience of viewing our collections at the Frick is informed by the context of the residence itself. Henry Clay Frick chose to live with the works from his collection, and we continue to celebrate this experience today in how we present our exhibitions. At the Breuer building, we will have a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to see these works in a very different context. The plan is not yet formalized, but the intent is to avoid recreating ourselves a few blocks away, and instead to see The Frick reframed in this very different way, architecturally and aesthetically. I’m intrigued and excited, and we feel that from the public when they ask us about it! The response has been tremendous.”

What should it be called? The Britney? or maybe the Fritney? the Freuer? or the Fret? In a recent talk Wardropper seemed to favor the Britney. The very traditional Frick is almost revolutionary today in its staid presentation and in fact was criticized on its 1935 opening by giants like literary and architectural critic Lewis Mumford for retaining Henry Clay Frick’s decorative objects. Calling the decorative objects bric-a-brac, Mumford disdained the Frick setting, which most of us love, as a “nuisance,” arguing that complex paintings are best shown on “the bare walls of a modern building.” He is about to get his wish.

The Frick Collection is located at One East 70th Street New York NY 10021. Closed Mondays; Tues-Sat 10 am to 6 pm; Sun 11 am to 5 pm

Julia Vitullo-Martin is a senior fellow at the Regional Plan Association. Contact her at @JuliaManhattan.

Stop by the Frick Collection after our upcoming tour of the Secrets of Central Park:

Subscribe to our newsletter