There are many superlatives possible when looking at New York City’s cemeteries — largest, smallest, most-filmed in. Today, we place our attention on the oldest cemeteries in New York City, focusing on those that are still intact — meaning, they still have bodies buried there and have gravestones or other markers indicating the locations of the bodies, or the location is recognized by the city as being a cemetery (and that is its primary designation) and is shown as such on maps. We found it necessary to put parameters because of the number of former cemeteries that exist in New York City, a few which may pre-date the ones here.

All of the oldest intact cemeteries date to before 1700 and span four boroughs of New York City. Buried within traditional graves or inside vaults are members of New York City’s most notable families and some of its most famous personages including Alexander Hamilton, Peter Stuyvesant, Lady Deborah Moody, and many more.

A visit to these cemeteries is truly a walk through the city’s history. Though Trinity Church’s cemetery may be the most famous, many of these are now in off-the-beaten-path locations and some are off-limits to the public unless prior arrangements are made.

1. St. Peter’s Episcopal Church Graveyard (Pre-1650)

It is believed that the burial ground at St. Peter’s Episcopal Church in the Bronx located at 2500 Westchester Avenue in the Westchester Square-area of the borough may have been established before 1650. The parish, one of the oldest in New York City, was organized in 1693 and the oldest extant gravestone today dates to 1716. An 1848 book The History of the County of Westchester notes that the earliest gravestone then was dated to 1702, so like in many cemeteries, the earliest markers have been lost.

The church erected its first building in 1700 on what was the village green, when this area of the Bronx was still part of the Town of Westchester. Six years later, Queen Anne of England bestowed upon the congregation a communion service that included a “chalice and paten, a communion table, a church Bible, a book of homilies, and a pulpit cloth.”

The current building, which dates to 1853, is listed on the National Register for Historic Places and is a New York City landmark. The landmarks designation report for the church states that it remains a “tangible reminder of the rural past of this section of the Bronx.” The cemetery also includes soldiers killed during the Revolutionary War, a vault for the Morris family, and some large mausoleums.

2. Gravesend Town Cemetery (1650)

The town plan for Gravesend was if not the first, one of the earliest planned communities in the United States. The town was settled in 1645 by Lady Deborah Moody, the first woman to receive a land charter in the colonies and by all accounts, quite a unique woman. Her out-of-the-box religious beliefs got her banned from London as well as Puritan Massachusetts where she first relocated to in the New World.

In the town plan of Gravesend, there were four quadrants within a 16 acre plot of land, each with ten houses surrounding a central common square. The common square in the southwest quadrant was used as the Gravesend Cemetery, which still exists today. Documents show that a cemetery was in operation here as early as 1650. Lady Moody herself is said to be buried in the cemetery, although her exact burial site is not known today. A plaque from the Gravesend Historical Society at the site notes that Revolutionary War soldiers are also buried here. Unfortunately, the gravestones from the 17th century are no longer there.

Because the Gravesend cemetery was a town burial place, it changed jurisdictions several times — in 1894 it became part of the city of Brooklyn, and in 1898 part of New York City when the five boroughs were consolidated. By the turn of the century, burials were less frequent, mostly for descendants of the original settlers who had plots left. In 1917, the city tried to return the cemetery to the Dutch Reformed Church which refused to take it. To this day, the cemetery is locked although you can see inside through the fences on the street. If you want access into the cemetery, you have to call New York City Parks & Recreation.

You can read more about the town plan for Gravesend in our book Secret Brooklyn. Get an autographed copy from us or a non-autographed copy on Amazon.

3. Flatbush Dutch Reformed Churchyard (1657)

The Flatbush Dutch Reformed Church at 890 Flatbush Avenue is one of the oldest standing churches in New York City, and its graveyard was in active use from about 1657 to 1913. The first church on this site in Flatbush was built in 1654, one of three Dutch Reformed churches formed in Brooklyn under the directive of Peter Stuyvesant, the Director-General of New Netherland.

Buried here are members of many famous early settlement families, including the Cortelyous, Lefferts, Lotts, Bergens and Vanderbilts. Beneath the church, in burials that pre-date the current building which was constructed from 1793 to 1798, are the bodies of Revolutionary War soldiers who died during the Battle of Brooklyn. The current church edifice, constructed 1793-1798 on the site of the previous one, is made of Manhattan schist that was quarried at Hell Gate.

4. Prospect Cemetery (1660)

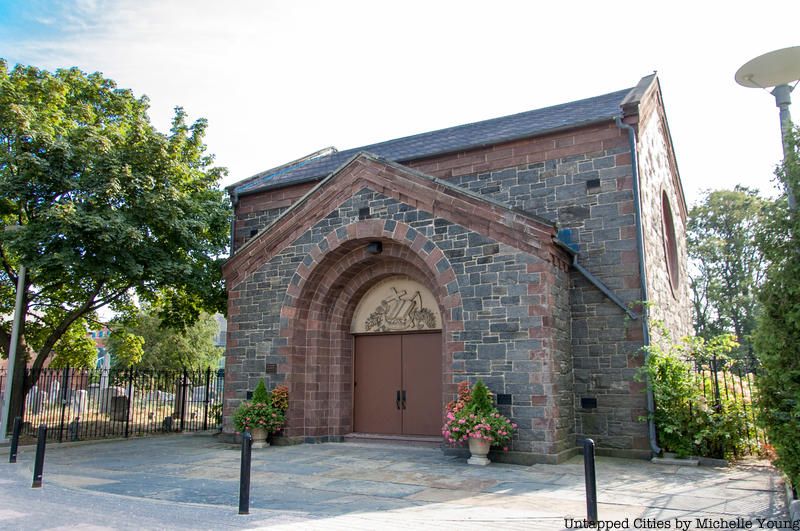

Locked up and largely forgotten amidst the hustle of Jamaica, Queens, Prospect Cemetery sits quietly, sandwiched between York University and an industrial zone. Located behind the Jamaica Long Island Railroad station, Prospect Cemetery was the burial ground for the First Presbyterian Church of Jamaica, originally the Old Stone Church, which was located a few blocks away on Union Hall Street. Though landmarked in 1977, the cemetery went through several decades of abandonment, disrepair, and vandalism. Today, the graveyard is somewhat overgrown, although the Romanesque Revival-style chapel has been restored.

Prospect Cemetery was established in 1660, according to the New York State Education Department plaque located here. New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission states that the earliest record of the cemetery is from 1668. In 1668, it became the public burial ground for the town of Jamaica, making it the first city cemetery in Queens. It would make sense that the burial ground was used for some years by the church before it was appropriated by the town. The cemetery increased in size over the years, but the original portion with the oldest gravestones sits within the narrowest portion of the cemetery. You can see this section from 158th Street.

Some of the notable people buried here include Egbert Benson, the first Attorney General of New York State, members of the Brinkerhoff, Sutphin, Van Wyck, Nostrand, Lefferts, Ludlam and Remsen families, and Revolutionary War activists including Increase Carpenter, Thomas Wicks, Henry Benson, Captain J.J. Skidmore, and Elias Baylis. The cemetery has about 500 gravestones, of which half are from the colonial era. The earliest tombstone still standing dates to 1709.

5. Northern Section of Trinity Churchyard (1662)

A lesser known fact about Trinity Church: the northern churchyard was not originally part of the property. In 1662, Peter Stuyvesant, gave the Burgomasters of New Amsterdam land to use as the public burial ground. In the Charter of the City of New York from 1868, it was referred to as “the new burial place without the gate of the city.”

In 1697 when New York was under British control, the first Trinity Church was built. In 1703, the northern cemetery was given to Trinity Church with the provision that the city could keep using it as a public burial ground which it did so until 1821, when the city passed the ordinance banning burials south of Grand Street.

Discover the Dutch history of lower Manhattan in our upcoming tour of the Remnants of Dutch New Amsterdam:

Tour of The Remnants of Dutch New Amsterdam

6. Flatland Dutch Reformed Churchyard (1663)

The Flatlands Dutch Reformed Church‘s graveyard was established in about 1663 and is still an active cemetery. The designation report on the National Register of Historic Places calls it an “ancient graveyard [which] is surrounded by large old trees and imparts an air of tranquil beauty to the whole setting.” Located at 3931 Kings Highway, between Flatbush Avenue and Overbaugh Place, the church was established in 1654, one of the three Dutch Reformed churches created in Brooklyn under the direction of Peter Stuyvesant that year.

The current white Greek Revival church that stands there today was built in 1848 and later enlarged. The New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission calls out the church as a “a living image of rural worship of a type which has all but disappeared from the City.” Buried in the graveyard is Reverend Ulpianus Van Sinderen, a Revolutionary War-era Dutch minister who was nicknamed “The Rebel Parson.” Underneath the pulpit of the church is buried Pieter Claeson Wykoff. His house in Carnasie is the oldest surviving structure in all of New York City. Like other colonial-era graveyards that began limiting burials, only those who already had plots could be interred here after 1910.

7. Old Springfield Cemetery (1670)

The Old Springfield Cemetery, a section within the Montefiore Cemetery in Springfield Gardens, Queens, is one of the oldest in the borough. Comprising about five and a half acres, the Colonial-era graveyard contains burials of the city’s first settlers, and here you will find names like Boerum, Nostrand and Remsen.

The Old Springfield Cemetery was in use from about 1670 to 1934, but the oldest gravestones have deteriorated to become unreadable at this point. You can walk or drive into the cemetery from an entrance on Springfield Avenue across 122nd Street, which is separate from the grander Montefiore Cemetery entrance. The road into the cemetery ends at a simple white chapel, that is still used. This non-sectarian cemetery is a unique spot amidst the Jewish Montefiore Cemetery.

8. St. Mark’s Church-in-the-Bowery

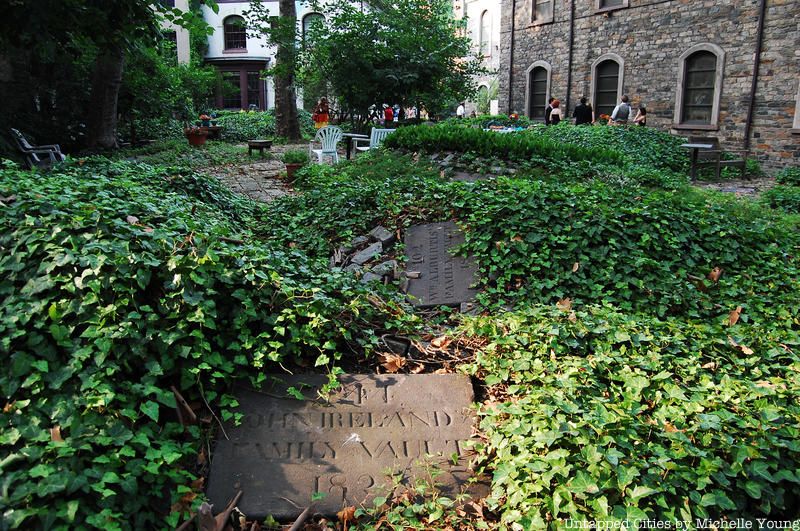

St. Mark’s Church in the Bowery is one of the oldest churches in all of New York City, and the second oldest in Manhattan. It has strong ties to the Stuyvesant family — Peter Stuyvesant built the first chapel that stood here in 1660 on what was his lrage farm. Peter and his kin are interred in the family vault underneath the church. The churchyard was dedicated to vault interments, and you can find numerous family vaults here. On our visit, we found names like Schermerhorn, Livingston, Tomkins, Suydam, and Sloughter, surrounded by ivy. The body of department store tycoon A.T. Stewart was stolen from a vault here leading to a sensational multi-year search.

The cobblestones in the burial ground were added with assistance from a few dozen teenagers in 1969, at a time when the graveyard was a hangout for drug users and subject to random dumping. The Reverend J.C. Michael Allen who led the redesign project told The New York Times, “A few people have complained to me about the cemetery project, but I don’t think they understand. There are many ways to honor the dead, but for me and the anguished people who are my parishioners, I think the best way to honor them is not to die with them, but to live with them.”

9. St. Ann in the Fields Church (1672)

Located in the Port Morris neighborhood of the Bronx, the church of St. Ann in the Fields is connected to the Morris family that settled the area. The church was built in 1840 on a field within the estate of Gouverneur Morris II, in honor of his mother Anne Carey Randolph Morris who was said to be a descendent of Pocahontas. Among the dozen or so Morris family members buried in the vault at St. Ann in the Fields include the first Gouverneur Morris, who drafted the United States Constitution, Judge Lewis Morris, the first governor of New Jersey, Major General Lewis Morris, who signed the Declaration of Independence, and Judge Robert Hunter Morris, a mayor of New York City.

The first Gouverneur Morrris served in the Continental Congress, the Constitutional Convention, minister to the Court of Versailles, and a United States Senator. According to the Landmarks Preservation Commission report on this church and graveyard, which are landmarks, Governeur Morris “framed the final draft of the Constitution as submitted to the States for ratification, and the beautiful, clear and forceful English of that instrument is almost entirely his work.”

10. The Trinity Church Graveyard (1681)

Not to be confused with the northern graveyard at Trinity Church, which predates this one, the southern churchyard was in use from 1681 to 1822. It is unclear how many people are buried here, but they include possibly Algonquin Indians who died on this site in a Dutch battle in 1643, numerous Revolutionary War dead, and perhaps the most famous of them all — Alexander Hamilton. Burials stopped in 1822, following a decision by Trinity Church in 1794 to stop new burials except for those that already had a family vault.

Other vaults exist below the church itself, such as the vault of the Bleecker family which were reaccessed after one descendent took decades to access and push for the restoration of the vault which had been “desecrated” by workers.

Next, discover the Dutch history of lower Manhattan in our upcoming tour of the Remnants of Dutch New Amsterdam:

Tour of The Remnants of Dutch New Amsterdam

This article was published with additional research provided by Ariella Rosen.