The New York Times morgue is a reliquary of information, a holdover from the era before digital archiving. Stories were cut by hand out of the newspaper and filed by author, by subject, and by persons mentioned in the piece. There are no dead bodies there, but hundreds of thousands of pounds of newspaper clippings. We’ll be showing you more from inside the morgue at a later time, but a recent visit turned up a mostly forgotten story about one of our favorite places, Grand Central Terminal.

One of the little-known research tips about the New York Times morgue is that it is one of the only places where you might find stories that never made it into the digital articles archive. This is because only the evening edition of the Times was put on microfilm and later scanned for online use, not the morning edition. There are articles that ran in the morning but were “killed” during the day to make room for new news.

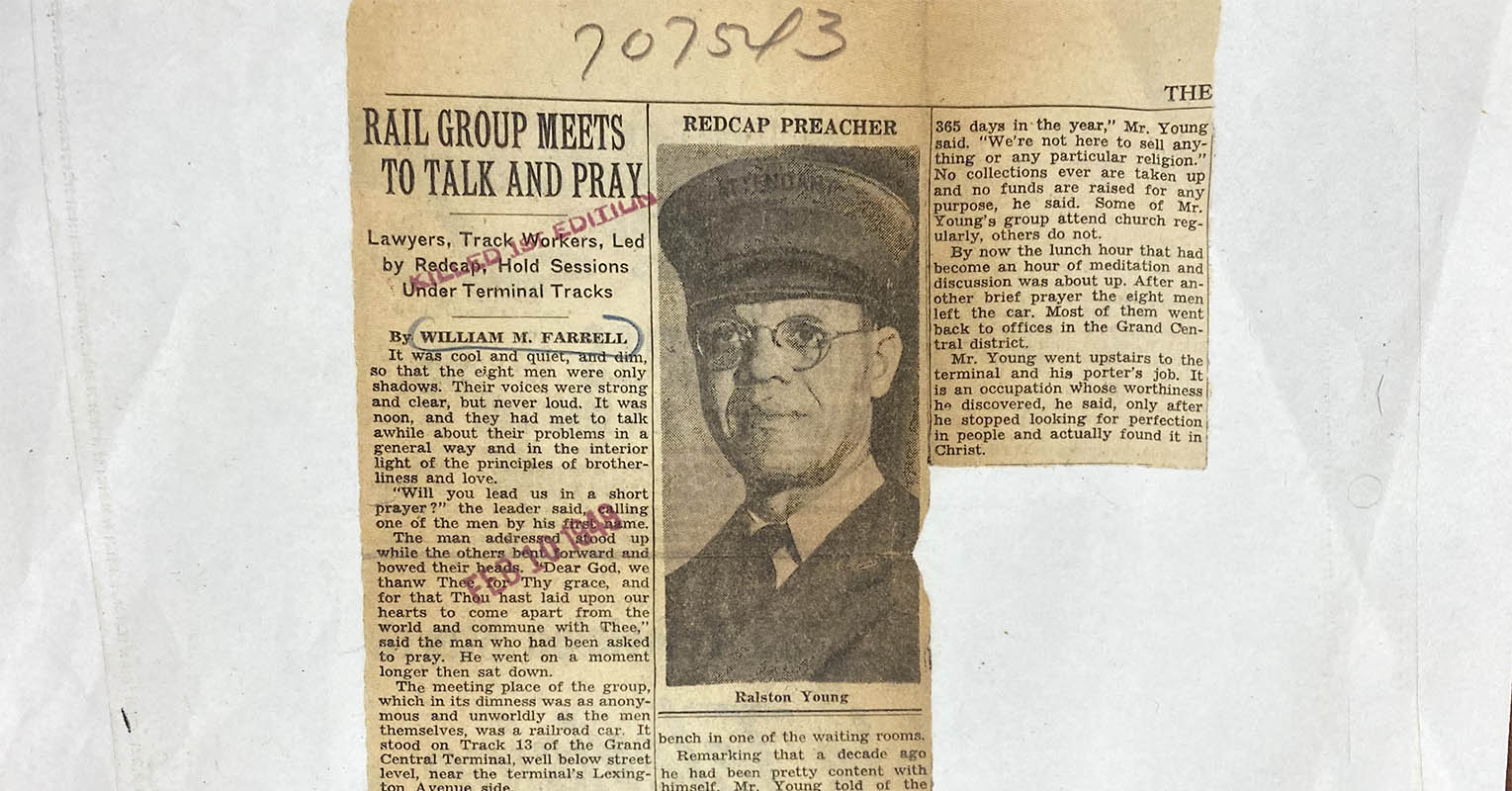

On a recent visit to the morgue, Jeff Roth, the last clip filer at the New York Times, showed us a story about a Red Cap in Grand Central. Forgotten in history, Ralston C. Young was once a well-known figure known as as the “Red Cap Preacher” for the lunchtime services he held in a railroad car on Track 13.

The Redcaps were porters that once carried passenger baggage in the train terminal, a service that no longer exists at Grand Central but is still active on Amtrak. This story about Young appeared on February 10, 1948. But if you search the New York Times archive, the first appearance for Young is in 1952 because the 1948 story was never microfilmed or digitized because it appeared in the early edition. If you look at the version stored in the morgue, it is stamped in red, “KILLED 1ST EDITION” “You would not be able to find that online,” Roth explains, “That’s probably the only copy in the world.”

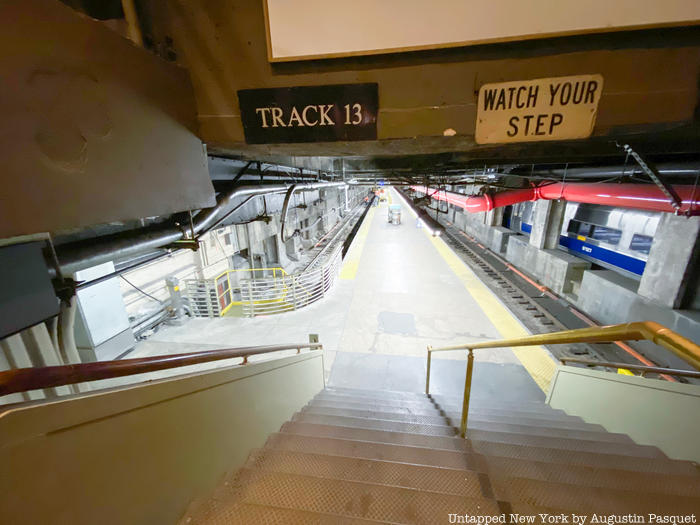

The story in question, “Rail Group Meets to Talk and Pray” is by William M. Farrell and is beautifully written. It opens with “It was cool, quiet and dim so that the eight men were only shadows.” It describes the thrice-weekly meetings which took place on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays over lunch on Track 13 for prayer and discussion led by Young. “The meeting place of the group, which in its dimness was as anonymous and unworldly as the men themselves, was a railroad car.”

There were about 35 people who were in the group, the article noting that the members crossed racial borders and included a range of occupations from railroad employees to an “advertising specialist, and some lawyers, railroad executives and physicians.” They had moved to the rail car on Track 13, which was used for storage then, after meeting for about a year on a bench in a Grand Central waiting room. At the very beginning, it was just Young and an elevator operator from a building nearby, but the group grew, until the railroad offered them the use of the storage car on Track 13. The Bronxville Review Press indicates that it was a Pullman car. At the time of the article, Young was 52.

The story does not mention that Young is a Black man, but at the time readers would have made the assumption and an accompanying photo of him helps illustrate. In a recent book, Boss of the Grips: The Life of James H. Williams and the Red Caps of Grand Central Terminal, author Eric K. Washington shows how being a porter was a stepping stone for Black upward mobility.

As described by the publisher of the book, Williams, the chief porter who trained and managed the Red Caps of Grand Central, believed that education was the key to a better life for Black Americans: “Williams famously provided a lifeline to black college and graduate students struggling to pay tuition. So much so that by the 1930s a typical magazine profile of the Red Caps read ‘Ph.D. Carries Your Bags.’ Williams’s alumni would go on to be famous singers, stage actors, political activists, civic leaders, and writers.”

Red Cap service that still exists at Amtrak in Penn Station

Red Cap service that still exists at Amtrak in Penn Station

Farrell, who wrote the 1948 New York Times piece about Ralston C. Young, was undoubtedly aware of the divide between railroad executives and the porters in Grand Central. It seems clear he wanted to highlight the uniqueness of this prayer group for welcoming people of diverse backgrounds. Young is quoted to say “We’re not here to sell anything or any particular religion. No collections ever are taken up and no funds are raised for any purpose.” Farrell describes the end of the lunch hour: “After another brief prayer the eight men left the car. Most of them went back to offices in the Grand Central district. Mr. Young went upstairs to the terminal and to his porter’s job. It is an occupation whose worthiness he discovered only after he stopped looking for perfection in people and actually found it in Christ.”

In 1952, a new piece on Young, who was now dubbed the “Bishop of Grand Central” appeared in the New York Times. He had become a lay minister and gave a sermon at Calvary Protestant Episcopal Church near Flatiron. In this article, he speaks about how he uses his religion in his job. “Everyone I carry for is not on a honeymoon or pleasure trip. Many are answering sick calls or notices of a deceased friend, and it is in these cases that I can put my religion to work and offer them more than a hand with their bags. I can offer them a willing and compassionate ear for their troubles, a word or two about how my belief in God has strengthened me in similar circumstances or even just an understanding smile.”

Track 61 under Grand Central

Track 61 under Grand Central

Looking up other mentions of Young, you can find that he gave a talk at Vassar, with the campus newspaper contending that “he is an example of a lost art—that of making it a business to help one’s fellow man.” He is even known to have been on the famous Track 61 at Grand Central Terminal, used by Franklin Delano Roosevelt (we recently debunked the long-held myth that a train car beneath Grand Central had transported FDR). Young was the subject of a documentary about his work as a “redcap evangelist” by the Episcopal Radio and Television Foundation and according to a 1961 New York Times article, shooting began in August on that very track beneath the Waldorf-Astoria.

You can even find audio recordings of Young for The Moody Bible Institute, which sound very much like an early podcast. From his own personal account, we learn that he was born on November 22, 1896 in Colon, Panama. His father died when he was just a young boy and he had to drop out of school in eighth grade to make money for his family. He arrived to the United States in 1917 as a shipyard worker at the Brooklyn Navy Yard during World War I. After some years, he was able to save enough to bring his mother and sisters to the U.S.

He began as a Grand Central Red Cap in 1924. From his descriptions, we know he made those recordings after the Met Life Building was completed in 1963. He says he worked there for 40 years, which would put the date to at least 1964. He mentions that when he started in 1924, there were 500 Red Caps, and at the time of the recording, there were only fifteen left. “That says something about what happened to rail travel,” he muses.

Young didn’t originally see the purpose of his work as a Red Cap, it was just a job in the Great Depression. In an AP story from 1945, he speaks of being ashamed at first to be working as a Red Cap and how he would hide if he saw one of his friends come into the terminal. But he says in the recording, “One day I discovered that God meant for me to be here. To be a Red Cap, that I was a minister, that Grand Central Station was my parish.”

He says that he was given Red Cap No. 42 when he started, so it seems very possible that the reference to Red Cap No. 21 in the 1948 New York Times article is incorrect (or Young simplified things in his account). The rest of the recording is an autobiography, but enacted with actors who play his father, mother, and other figures who made an impact on his life.

A 1942 article in the Baltimore Afro-American Paper announced Young’s marriage to Ms. Sadie K. Morgan of Greensboro, North Carolina which took place at the end of 1941. Over the years, articles in many newspapers reported on awards and talks Young gave around the East Coast about his ministering in Grand Central, but the trail goes cold seemingly around 1979. The last mention we’ve found so far in the South Buffalo-Seneca News about a speech he was giving at an Episcopal Church when he was 82! We have not found any death notices so far on Young. Does anybody reading know what might have happened to the famous Red Cap Preacher?

Join us on our upcoming tour of the Secrets of Grand Central Terminal

Discover more secrets of Grand Central by looking inside the lost and found and learning if the clock is really worth $20 million!