How NYC Subway, LIRR, and Metro-North Responds to Snowstorms

Snow blowers, throwers, plows, and more specialized equipment help keep NYC moving in the snow!

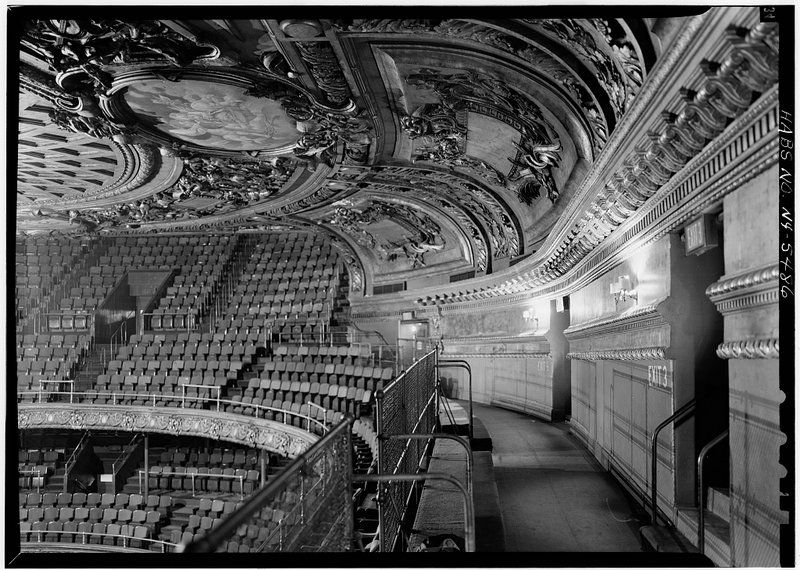

Image from Library of Congress

We put out an open call on our Facebook page with the question: “If you could bring back a long-gone building from the past in NYC, which would it be?” We received nearly a hundred comments and replies! Some even uploaded images of their choices, adding to the excitement of the feed. In one of our first-ever reader input article, we’re sharing the results of the informal poll.

Bringing back the original Penn Station was the runaway favorite, garnering over 50% of the votes. Designed by Charles McKim of McKim, Mead & White, Penn Station is the poster child of what happens when a building isn’t landmarked, and is in fact, often credited with being the sacrifice that led to the creation of the New York City Landmarks Law. In reality, the loss of a number of other buildings combined with Penn Station led to the fever pitch call, but Penn Station was certainly the most high-profile. It was built in 1910 and torn down in 1963.

Penn Station is particularly dear to us at Untapped New York because of our long-running tour, the Remnants of Penn Station that our Chief Experience Officer Justin Rivers developed out of his off-Broadway play The Eternal Space. In fact, Justin met the Untapped New York team for the first time inside Penn Station, so yep…feelings. We are regularly tracking down where the eagles of Penn Station have gone, taking road trips around the East Coast. We even got a call from Kentucky recently, when a reader and landscape architect thought he may have found some lost eagles (sadly, we confirmed that they were not from Penn).

Our readers wrote comments like, “The real Penn Station, absolutely,” “Penn Station! It’s criminal it was demolished,” “Penn Station…’nuff said” and quoted Vincent Scully (“One entered the city like a god. One scuttles in now like a rat.”). Untapped New York writer Jeff Reuben added, “If I were to bring back a lost building, it would have to be one with some public access and it’s hard to think of anything that matches the original Penn Station.”

Although Penn Station’s demolition was a terrible loss, the current station is incredibly filled with relics that still remain from the original station if you know where to look! Join us on our next tour!

Source: New York Public Library

With 7% of the votes, the Singer Building came in second. Never heard of the Singer Building you say? Well, it was once the world’s tallest building. If it was still standing, you’d see it right near the World Trade Center next to Zuccotti Park and Liberty Street and Broadway. It was built in 1908, designed by the architect Ernest Flagg for the Singer Company. One reader wrote, “Singer building. It was effing gorgeous. And it was replaced with a black box that has no style or personality.”

In 1961, the Singer Company sold the skyscraper to US Steel when the company moved to Rockefeller Center. The building’s shape, a narrow tower on a base, was considered not conducive to modern real estate needs (though the setback was a deliberate design by Flagg). The red brick, limestone, and terra cotta building was demolished in 1967 and replaced by the black steel tower you see today.

Photo by James and Karla Murray

The Twin Towers tied with the Singer Building with 7% of the votes. Of course, these buildings fall into a different category than the first two, as they were lost due to the terrorist attacks on 9/11. Designed by Minoru Yamasaki as lead architect and Emery, Roth & Sons as associate architects, the Twin Towers were also the tallest buildings in the world when they opened in April 1973. They were not particularly beloved when they were standing, with heavy criticism coming even before construction because it required the destruction of the Radio Row neighborhood. Aesthetically, architecture critics, urban planners, and even the public also criticized it.

But the circumstances surrounding their collapse gave the Twin Towers a radically different position in urban culture. One of our readers captured it well, writing they would bring back “WTC [World Trade Center] with all the people. ☹️” No matter what you felt about the buildings aesthetically, the tragedy has placed the buildings in the realm of the hallowed for New Yorkers. Furthermore, with the proliferation of blue glass throughout New York City since 9/11 (particularly at density in developments like World Trade Center and Hudson Yards), we think people are yearning for the level of texture that was provided on the Twin Towers.

Collectively, the older versions of Madison Square Garden came next. There were votes for the first two versions starting from P.T. Barnum’s Great Roman Hippodrome which was standing from 1874 to 1890. It was renamed Madison Square Garden in 1879 when the William K. Vanderbilt became the operator.

Stanford White designed the next iteration of Madison Square Garden, employing a Moorish architectural style. It was here that White had one of his apartments for the purpose of seduce young women and where he met his untimely end in 1906, shot in the head on the rooftop garden by the jealous husband of White’s former paramour, Evelyn Nesbit. This version of Madison Square Garden would be demolished in 1925 after which it moved to the West Side, keeping the Madison Square name. Rediscover the Madison Square Gardens we’ve lost in an upcoming episode of our virtual series, Lost New York!

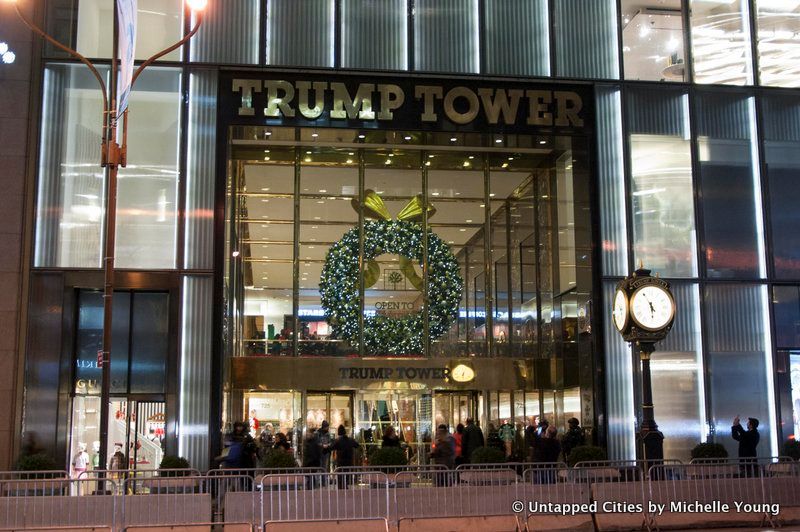

Where Trump Tower now stands was the former Bonwit Teller flagship store

Tied with the Madison Square Gardens was the Bonwit Teller Building, originally a 1929 department store of Stewart & Company that was demolished in 1980 and replaced by Trump Tower. One reader writes, “I miss the Art Deco bas reliefs that graced the Bonwit Teller building on 5th.” Designed by Warren and Wetmore (of Grand Central), the reliefs were one of the many things that were celebrated in the design of the building. The store was so celebrated that Eleanor Roosevelt attended the opening.

The New York Times described the limestone building as having an “entranceway that was a stupendously luxurious mix of limestone, bronze, platinum and hammered aluminum” and that protest regarding saving the building “came both too late and too early. It became a Bonwit Teller store in 1930 and lasted until 1979.

Had we kept the Crystal Palace, New York City might feel a lot more like Paris. Taking up two blocks on 6th Avenue between 40th and 42nd Street, the Crystal Palace was an architectural feat of iron and glass with a massive dome built in 1853.

Accompanying the structure was also “New York City’s first skyscraper,” an octagonal observation tower taller than Trinity Church. A million visitors later, the entire Crystal Place went up in flames due to arson in 1858. Today, the site is now part of Bryant Park.

In 1893, William Waldorf Astor hired renowned architect Henry Hardenbergh, who would later design The Dakota apartments, to build a 13-story grand hotel on the site of what was his family mansion. At the time, the Waldorf Hotel was the largest and most luxurious hotel in the world, with 450 rooms. Meanwhile, John Jacob Astor IV owned the other end of the block. Four years after the construction of the Waldorf, John Jacob built a 17-story hotel within feet of the Waldorf, using the same architect. In time–and having good business sense–it was decided that the hotels should be physically joined together by a long hallway. The combined hotels, opening in 1897, became the largest hotel in the world.

The sinking of The Titanic took the life of John Jacob Astor IV in 1912, and William died of a heart attack in 1919. The land where the grand hotel sat was sold in 1928 to a developer, who demolished the building and erected the Empire State Building. Learn more about the early history of the Waldorf Astoria in our upcoming talk with historian David Freeland, author of American Hotel: The Waldorf-Astoria and The Making of a Century.

Though Coney Island was a resort area since the Coney Island Hotel opened in 1829, it had its humble beginnings as an amusement center with Paul Boyton’s creation of Sea-Lion Park in 1895. In 1903, Luna Park replaced Sea-Lion Park. It was not the only amusement park on Coney Island of course, there was Steeplechase Park, Astroland, and Dreamland as well but Luna Park was quite the spectacle.

Some highlights of the Oriental-themed, over-the-top Luna Park included the Electric Tower — the centerpiece of the amusement park — a lake, and elaborate lighting schemes on all the domes, minarets, and buildings. Luna Park was also host to some less savory moments, like the electrocuting of Topsy the Elephant, the “Igorrote Village” during Luna Park’s 1905 summer season, which featured Filipino tribesmen titled “head hunting, dog eating savages,” , “A Trip to the Moon,” in which riders entered a spacecraft and embarked on a simulated ride through space, greeted by miniature moon men, and the Infant Incubators.

A 1944 fire destroyed most of Luna Park, causing its tower to start spitting out embers. Yet another fire destroyed what was left of the park a few weeks later. A new Luna Park opened up in 2010 on the former site of Astroland.

Another unfortunate victim of Coney Island’s raging fires was the Elephant Colossus. From 1885 until 1896, Coney Island had the most fantastical of hotels: the Elephant Hotel (also called the “Elephantine Colossus” or “Elephant Colossus”). It was 200-feet tall with a gilded crescent and stood proudly and prominently on Surf Avenue and West 12th street. James Lafferty designed the 12-story building with 31 rooms, even calling it the “Eighth Wonder of the World.”

Although containing grand spaces like a concert hall, an observatory, and an events bazaar, it eventually became a hotspot for prostitutes, but even the gimmick there didn’t last long. The Elephant Colossus was pretty empty by the time a fire destroyed it in 1896. A cousin of the Colossus, Lucy, still stands in New Jersey, however and this month, will host some guests from Airbnb.

The original Metropolitan Opera House opened in 1883 on 39th Street and Broadway, closer to the city’s emerging mansion district. Its arrival spurred the development of the theater district that centered around Long Acre Square. The opera house was designed by architect J. Cleaveland Cady. The interior of the Metropolitan Opera House was redesigned by Carrère and Hastings after a fire in 1892. The gilded auditorium had a proscenium arch inscribed with the names of six classical composers and elaborate, carved ceiling details.

When the Metropolitan Opera decided to relocate to Lincoln Center in the 1960s, the future of the existing building was called into question. Ironically, the Metropolitan Opera Association supported its demolition, fearing competition if another opera company took over. Due to questions over the integrity of the architecture, the building was not landmarked. It was demolished in 1967 and replaced with an office skyscraper.

The home of the historical Brooklyn Dodgers was demolished in 1960 just five years before the inception of the Landmarks Preservation Commission. In 1962 the Ebbets Field Apartments, an affordable housing complex, was completed and still exists today.

Besides the name of the building, there are a few markers of the past in tribute of the lost baseball stadium. A home plate marker on the sidewalk of a parking lot and a cornerstone inscribed with the words “This is the former site of Ebbets Field.

The Astor was a Neo-Classical and Second Empire styled hotel and built on Broadway at Forty-fifth Street. It had a green copper mansard roof, a Louis XV-style Rococo ballroom, a theater and a rooftop garden for entertainment, drinking, and dining.

The Astor closed in 1972 because the building had maintenance issues. It was slated to be destroyed and turned into an office tower along with several other theaters on the block, but the community intent on preserving the integrity of the theater inside fought against its destruction for twelve years. They were unsuccessful and the Astor was torn down to make way for what is now 1515 Broadway and at the next block, the Helen Hayes Theater, the Morosco Theater, and the Bijou theater were torn down to build the Marriott Marquis Hotel. The hotel itself lives on in an illustration on Dr. Brown’s Soda cans.

There are some other great locations that came in through the open question on Facebook, including those who wanted to bring back automats like Horn & Hardart, the National Academy, the barge office at The Battery, the Bowery Theater, the Savoy Plaza Hotel, and the aforementioned Helen Hayes Theater. On very opposite ends of the spectrum, one person voted to bring back Carnegie Deli while another put forth Fort Amsterdam. There was also a vote for a building still standing, like 2 Columbus Circle that was significantly altered (now the Museum of Arts & Design), one vote for the peep show Show World in Times Square, and one vote for no buildings at all. There were several votes for the Roxy Theater, after this article was published. Then there are these author’s personal favorites, the old Post Office in City Hall (known as Mullet’s Monstrosity) and the Vanderbilt Mansion on Fifth Avenue, which received another reader vote.

Well that was fun! Join us on our next tour of the Remnants of Penn Station!

Subscribe to our newsletter