Last Chance to Catch NYC's Holiday Notalgia Train

We met the voices of the NYC subway on our nostalgia ride this weekend!

A typist wearing a flu mask in New York City in October 1918. Photo from National Archive

Ever since New York became a state in 1788, New York City has faced numerous epidemics that have endangered much of its population. From the coronavirus to yellow fever outbreaks in 1795, New York City, one of the United States’ largest and most diverse cities, has had to worry about protecting the health of its citizens. The city has learned quite a bit about dealing with epidemics since the late 1700s, but the ride hasn’t been so smooth for New Yorkers over the last 250 years.

The quarantine station on Staten Island. Image from New York Public Library.

The quarantine station on Staten Island. Image from New York Public Library.

In August 1793, a yellow fever epidemic hit Philadelphia, killing around 5,000 residents out of 50,000. By September 1793, more than 20,000 Philadelphia residents fled the city. Benjamin Rush, considered as the founder of American medicine, helped to organize the government response to the Philadelphia epidemic and used bloodletting to treat sick patients. During this time, however, New York had quarantines against refugees and goods from Philadelphia, although New York sent Philadelphia $5000 and food supplies.

However, just two years later in 1795, yellow fever emerged in Manhattan, lasting until 1803. Although yellow fever killed dozens of New Yorkers in the first year, people were reluctant to publicize the epidemic due to fear of business loss and of mass immigration away from New York. Doctors also didn’t initially realize yellow fever was spread by mosquitoes, many hypothesizing it began from rotting coffee or from poor sanitation in slums. In 1798, around 800 people died of yellow fever in New York with a fatality rate without treatment of nearly 50%. In 1805, another 270 people died from yellow fever in New York, even after the epidemic died down.

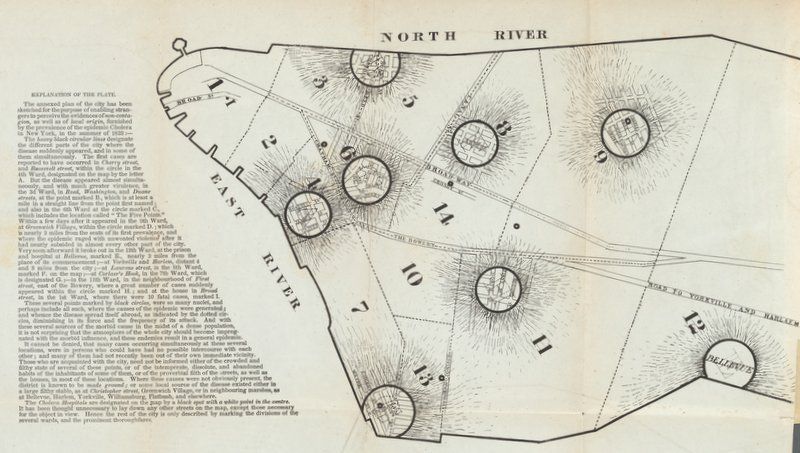

Map of cholera outbreaks in Manhattan, 1832. Image from NYPL Digital Collections.

New York faced three major waves of cholera from 1832 through 1866, killing anywhere from two to six Americans a day. Cholera, an infection of the intestine, first struck India near Calcutta in 1817, eventually spreading through the Middle East and Europe. New York immediately quarantined incoming ships from Europe after news spread of a cholera epidemic, yet New York once again was reluctant to make public announcements about cholera’s spread.

Cholera hit New York around June 1832, and within a few months cholera had killed over 3,500 New Yorkers. The disease mainly impacted poor African Americans and Irish who lived in New York’s slums. Cholera killed close to 1,000 more people by 1834, but the second wave hit New York in 1849 when over 5,000 people died. Despite efforts by the city to stop the disease’s spread, it killed another 2,000 people in 1854 and 1,100 people in 1866, making the cholera epidemic one of the most disastrous in New York’s history. The map above was created to help illustrate how the disease appeared simultaneously in multiple locations in Manhattan in people who had not traveled to other parts of town, in a seeming attempt to show that the disease could emerge from poor hygiene and general cleanliness of the area. We know now that cholera can be caused and spread by contaminated water.

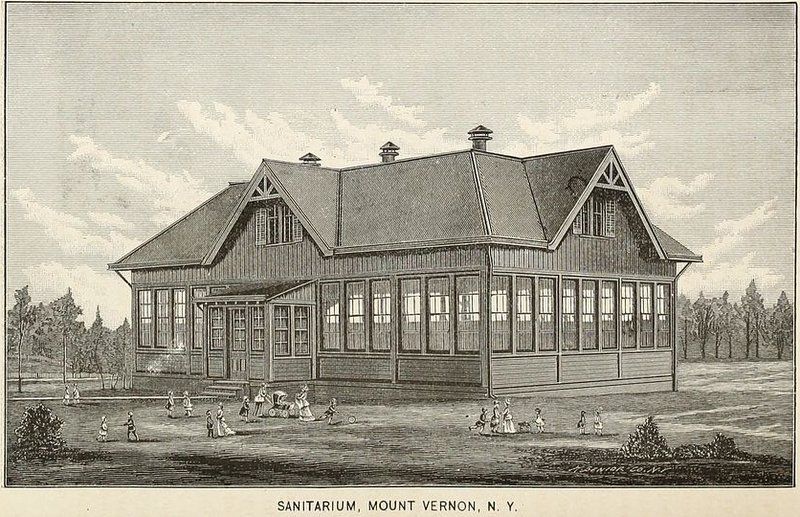

From the 1884 New York Infant Asylum Report. Image from Wikimedia Commons.

Diphtheria, a bacterial disease that causes a thick buildup in the back of throat, killed thousands of New Yorkers, especially children, throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries. By the late 1800s, a diphtheria vaccine was developed, but it didn’t become widely available until the 1920s. Diphtheria had two major waves in 1881 and 1887, killing 4,900 and 4,500 people respectively. By the 1890s, the death rate slowed, yet many families were reluctant to send their children to school due to the disease’s highly contagious nature.

The above image comes from the 1884 New York Infant Aslym report where the President of the Asylum wrote next to the engraving, “It will be noticed that the number sheltered in 1887 is 1165 against 1198 in 1886. This is accounted for by the reports of the Resident Physicians both at Sixty-first street and at Mt. Vernon show-ing the outbreak of diptheria which though soon checked compelled a quarantine which prevented for a period the receiving of further inmates. All this is now happily at an end, and we are going on with our work untrammelled by any such unfortunate restrictions.”

From the New York American, 1909. Image from Wikimedia Commons.

Typhoid, a bacterial infection that leads to a high fever, spread to New York in waves starting in the 1840s until the early 1900s. Between 1847 and 1848, nearly 2,400 New Yorkers died of typhoid, and the disease killed over a thousand New Yorkers in 1851, 1864, and 1865. By the early 1900s, however, typhoid became much more serious once Mary Mallon, known as “Typhoid Mary,” began infecting New Yorkers without even realizing it.

Emigrating to New York in 1883 as a teenager, Typhoid Mary, who was born in 1869, worked as a chef for numerous families in New York City and Long Island despite being an asymptomatic carrier of typhoid, which means that she could spread the disease without experiencing any symptoms. Typhoid Mary supposedly infected at least 51 people and was quarantined on North Brother Island in the East River for the last 23 years of her life. Although she only spread the disease to what seems to be a small number of people, she became the face of the epidemic in New York. By 1914, a typhoid vaccine was developed and licensed.

A typist wearing a flu mask in New York City in October 1918. Photo from National Archive

In 1918, the “Spanish Flu” pandemic infected 500 million people around the world, 27% of the world’s population, and killed anywhere from 17 million to 50 million people. In the first year of the pandemic alone, the average life expectancy in the United States had already dropped by 12 years. Out of 5.6 million people living in New York, about 33,000 succumbed to the flu, a number much lower than expected since New York was the most populated and most diverse city in the U.S. at the time.

To prevent the flu from spreading, the Board of Health created a timetable system to regulate the opening and closing hours of businesses while easing congestion of public transit systems during rush hours. Additionally, a “clearinghouse plan” was installed to establish 150 temporary health centers in the city. Schools, theaters, and offices were also kept open during the pandemic since people were often safer in contained areas. The Board of Health informed students of ways to keep healthy during the height of flu season, which especially benefited immigrant families.

Chart by the Department of Health of New York City, 1916. Photo from Wikimedia Commons.

Chart by the Department of Health of New York City, 1916. Photo from Wikimedia Commons.

The 1916 New York City polio epidemic infected several thousand people while killing over two thousand, primarily in Brooklyn. Polio, On July 17, 1916, Brooklyn officially announced the existence of a polio epidemic after a handful of people tested positive at a Brooklyn clinic. In June, there were over 100 cases of infantile paralysis in Brooklyn, which continued to grow across the city until the end of the year. The disease remained prevalent in the U.S. until the development of Jonas Salk’s polio vaccine in 1954.

During the height of the epidemic, movie theaters and other public places were closed, public gatherings were mostly canceled, and children were discouraged from going to swimming pools or beaches. The houses of infected patients were marked with placards and families were quarantined. Simon R. Blatteis of the Bureau of Preventable Diseases organized a special staff of medical inspectors and nurses to visit all cases daily, and by July 1916, Blatteis had established six clinics in Brooklyn to receive polio victims.

Smallpox has been a major cause of death every since the early colonial days, with a major outbreak in 1633-1634 killing around 70% of the Native American population. In 1770, Edward Jenner developed a smallpox vaccine from cow pox, and the last case of smallpox was in 1949. However, smallpox killed many New Yorkers during the 19th and 20th centuries: Smallpox killed nearly 2,000 people in both 1872 and 1875 and killed hundreds of New Yorkers each decade during the 1800s.

Yet in March 1947, New York experienced a smallpox outbreak, which only affected 12 people but led to the vaccinations of over 6,350,000 adults and children within three weeks of the outbreak’s discovery. On February 24, 1947, a rug merchant from Maine named Eugene Le Bar fell ill after boarding a bus in Mexico City en route to New York. Despite his fever and rash, smallpox was ruled out since he had a smallpox vaccination scar. Le Bar died on March 10, yet two patients on the same floor as Le Bar developed the same fever and rash as Le Bar and were subsequently diagnosed with smallpox. A handful of other people admitted to the Willard Parker Hospital where Le Bar was staying developed smallpox,

By early April, the public was informed of the smallpox outbreak, and New York City Mayor William O’Dwyer announced that everybody in the city was to receive a smallpox vaccination. Yet, the Health Department at the time only had 250,000 individual doses of vaccine and 400,000 doses in bulk. O’Dwyer met with seven American pharmaceutical companies, which together developed 6 million vaccine doses for the entire city in three weeks. Vaccination clinics were established everywhere from hospitals to police stations to schools, and volunteers went door-to-door urging residents to be vaccinated. More than 600,000 New Yorkers were vaccinated in the first week, and by May 3, 1947, the last vaccination clinic closed.

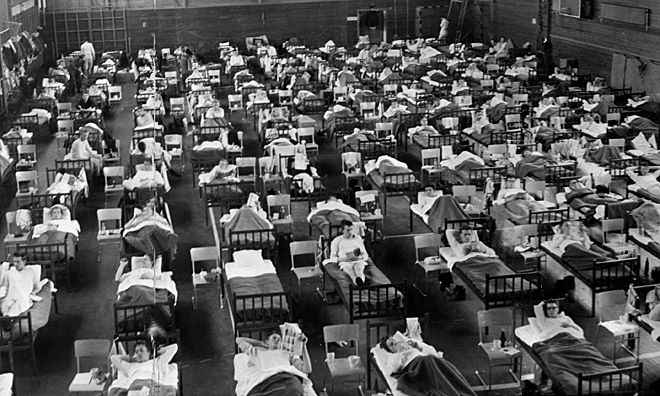

Patients being treated for “Asian Flu” in Sweden in 1957. Photo from Wikimedia Commons.

In 1956, the “Asian Flu,” a pandemic outbreak of influenzavirus A that originated in China, spread through East Asia and into the United States, killing between one and two million people. By late September 1957, the New York Health Department confirmed 350 cases of the flu in New York, and by early October, the Health Department reported that nearly 11,000 people complained of flu-liked symptoms. By 1958, the pandemic was responsible for 60,000 “excess deaths” in the U.S., or deaths that exceed what would normally be expected.

The first Asian Flu vaccine administered in New York took place on August 16, 1957, by Dr. Joseph Ballinger at Montefiore Hospital, and the vaccine was judged to be 45 to 60% effective. The flu took the lives of thousands of New Yorkers, but 5.4 million doses of the vaccine were released nationwide by mid-September.

Abandoned buildings Staten Island’s Seaview Hospital where tuberculosis was treated and a cure was being researched

In New York City during the 1980s, tuberculosis dramatically spread throughout the city, with over 3,800 New Yorkers receiving a tuberculosis diagnosis in 1992. By 1990, New York City had 15% of the country’s cases, and by 1991, 50 people out of 100,000 New Yorkers had TB. Among black men aged 35-44, the incidence was a surprising 469 out of 100,000 people. Cases in New York in children under 15 rose by 97% as well.

Yet completion of TB treatment was a grim 60% in 1989, which meant that many infectious patients were threats to others. Yet, New York took action to lower the number of TB cases to 1,700 in 1997, with the rate of TB in children falling significantly. New York developed directly observed therapy (DOT) programs to improve treatment completion rates, and infection control was improved in institutional settings. It was also in New York City, at Staten Island’s Seaview Hospital that the cure for tuberculosis was found.

Keith Haring created this mural at Woodhull Medical Center, a personal gift to the hospital which Haring admired for its dedication to pediatric AIDS research and treatment.

HIV/AIDS, the sixth leading cause of death in the United States among adults aged 25 to 44, has claimed the lives of more than 100,000 New Yorkers. First documented in 1981, the HIV/AIDS outbreak was first identified as a “gay-related immunodeficiency disease,” but soon after it was discovered that intravenous drug abusers also were infected. As more and more people were diagnosed with the disease, New York started taking drastic measures to try to find a cure and to encourage safety during drug use and sex.

Community advocacy organizations like the Gay Men’s Health Crisis and ACT UP (AIDS Coalition To Unleash Power) helped many HIV/AIDS patients become adjusted to life with the disease. New York City records note that by 1987, $400 million had been spent on AIDS services. Hotlines were created to provide counseling for those affected, and new needle exchange programs were established in New York to prevent the spread of the disease. Despite these efforts, AIDS became the leading cause of death for men between 25 and 44 and for black women between 15 to 44 in the 1980s.

St. Francis Preparatory School in Queens where the swine flu outbreak began in New York City. Photo by Jim Henderson from Wikimedia Commons.

The swine flu, a pandemic of a novel strain of the influenza A/H1N1 virus, began in the spring of 2009 and claimed the lives of 105 New York City residents and 101 residents of New York state. The swine flu killed around 3,400 people in the United States and infected around 115,000. On April 24, 2009, 150 students at St. Francis Preparatory School in Queens complained of flu-like symptoms, and two days later the CDC confirmed that the cases were associated with swine flu.

New York’s first death occurred just a month later on May 17 when the assistant principal of the school succumbed to the disease,, and by July 24 there were 2,738 confirmed swine flu cases. By January 2010, the flu started to die down, but the swine flu went down in history as one of the most costly pandemics in United States history.

The B110 bus that goes between Williamsburg’s Hasidic neighborhood and Borough Park

In 2019, New York City faced a substantial increase in measles cases from previous years, with 423 confirmed cases by May. New York had previously faced a measles outbreak in the 1980s, when the annual death rate fluctuated between 2,000 and 10,000 people. The areas of Williamsburg and Borough Park in Brooklyn were most affected by the outbreak, and on April 9, 2019, Mayor de Blasio declared a public health emergency.

The declaration required mandatory vaccinations in these areas and charged a $1,000 fine for those who refused. In June 2019, New York enacted a new law repealing religious and philosophical exemptions for vaccination. By early September, the Health Department declared the outbreak to be over.

Subscribe to our newsletter