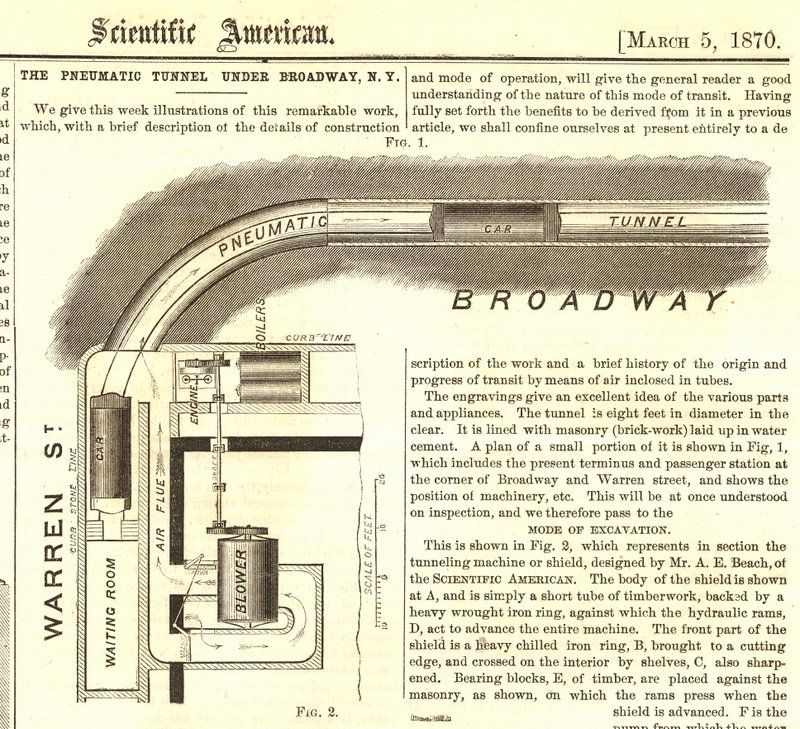

Before New York City’s modern subway system was established with the Interborough Rapid Transit Subway in 1904, there were a handful of attempts at underground transit — the first of which was powered by none other than compressed air. In 1870, Alfred Ely Beach, an inventor and editor of Scientific American, developed a demonstration subway line running on pneumatic technology. The subway, called the Beach Pneumatic Transit, lasted from 1870 to 1873 and was a one-block, single-track, single-car line below Broadway from Murray Street to Warren Street in Tribeca. Curiously, this technology remains at the forefront of transit advances even today — pneumatics is what powers the Hyperloop project.

Beach first proposed the creation of a tunnel underneath Broadway that would serve as a horse-drawn subway system in 1849. However, after reading about pneumatic experiments in England, Beach built a 107-foot-long model of an underground tube that he showcased in 1867 at the American Institute Fair. According to a New York Times article, “The propulsion method was relatively simple: a massive steam-powered fan forces air into the tunnel to push the car along, and when the current is reversed, a vacuum is created, propelling the car in the other direction.”

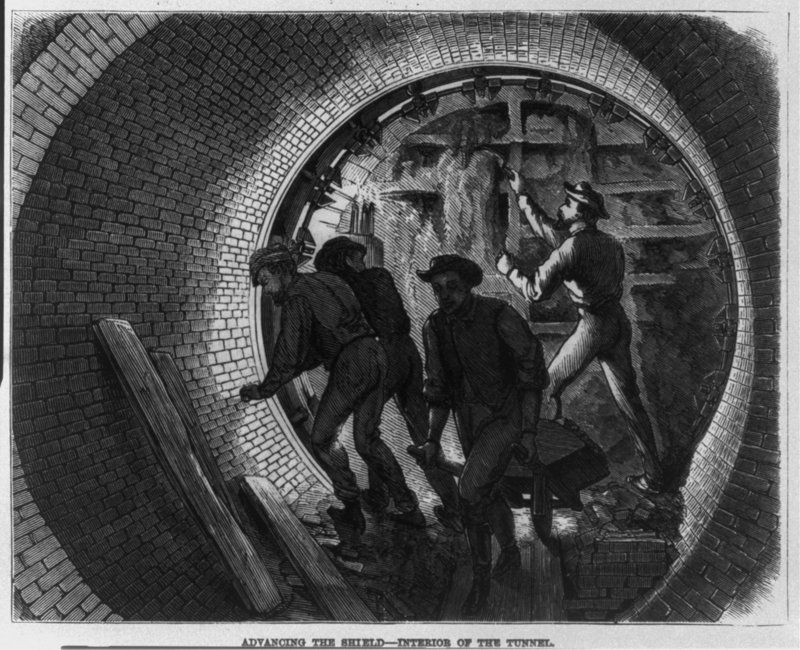

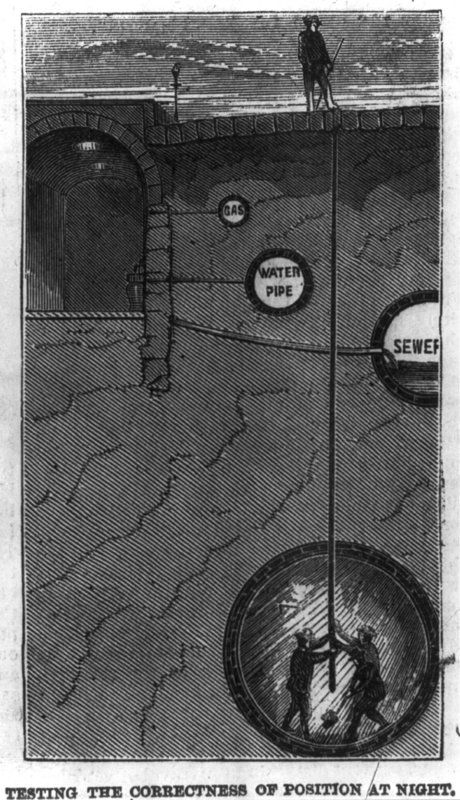

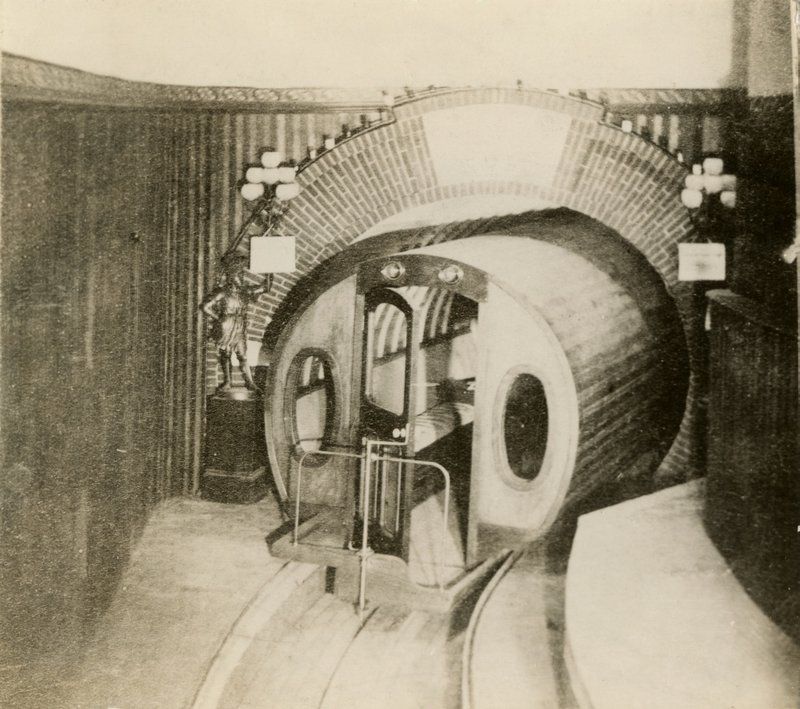

The Beach Pneumatic Transit Company began the subway line’s construction in 1869 after Beach put in $350,000 of his own money for the project. Beach used a tunneling shield, a temporary support structure, to allow for safe excavation without disrupting the street above. The tunnel was completed in just under two months.

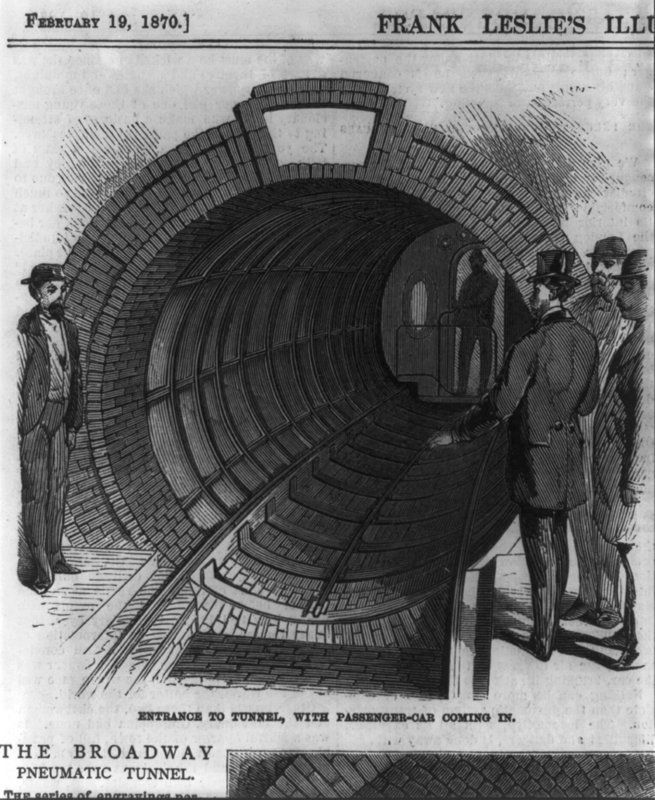

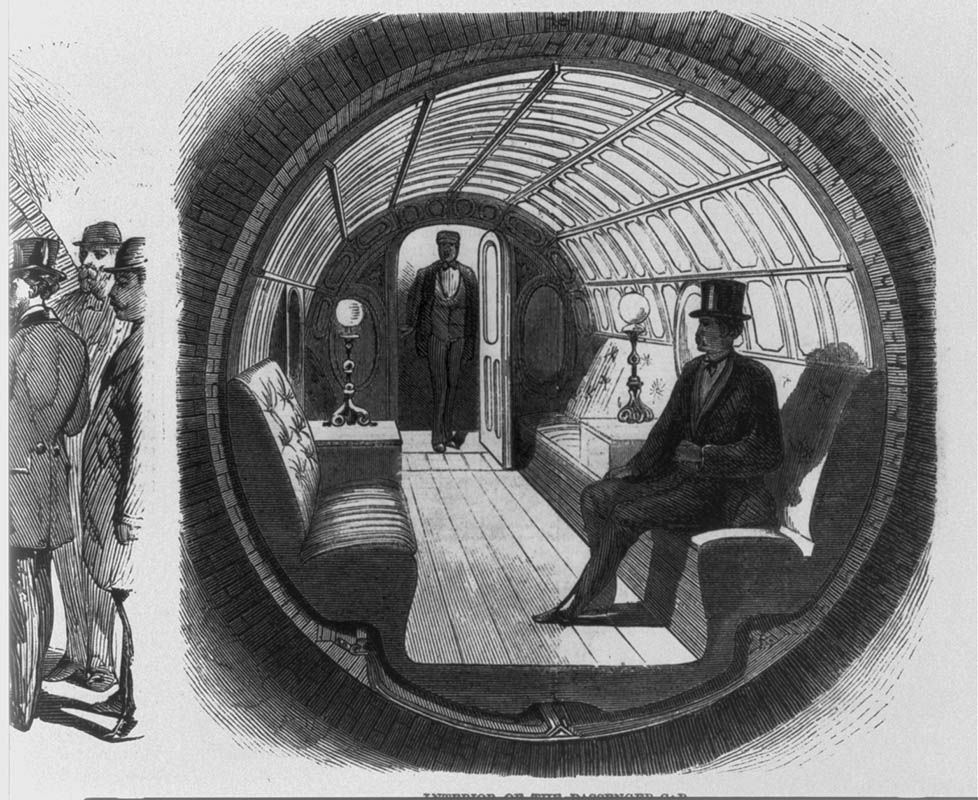

According to an 1870 Scientific American article, air is forced into the tunnel by a gigantic blowing engine, which is supported by a 100-horse power steam engine that could deliver 100,000 cubic feet of air per minute. The pneumatic car had a circular form with upholstered seats for 18 people. The article notes that “passengers may await the arrival of a car with as little inconvenience as they could in the best steam railway stations, and without any of the annoyances that attend the waiting for street cars at street corners.”

Despite the project’s initial success, Beach’s application for a permit from the Tammany Hall city government was denied by William “Boss” Tweed. At the time, Tweed hoped to construct an elevated railroad throughout Manhattan, and he felt that Beach’s subway system would pose unnecessary competition for this project. With little support from the city, Beach began to construct the subway in secret by claiming he was building a pneumatic mail delivery system, all the while building his subway beneath a rented storefront across the street from City Hall. Tweed later amended a permit to allow for excavation of a single large tunnel in order to simplify construction.

Since the subway only ran for one stop, it served mainly as an attraction for people who could ride it with a 25-cent fare. A significant portion of proceeds went to the Union Home and School for Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Orphans. According to PBS, over 400,000 visitors rode the subway in its first year of operation, enjoying the chandelier, grand piano, and fountain in the station.

The tunnel started at a station under the south sidewalk of Warren Street and ran east into Broadway, curved south, and ran through Broadway to Murray Street, a distance of around 300 feet. Plans for the subway noted that it would extend to Central Park, which would extend at least five miles, yet each time Beach proposed subway plans, they were vetoed at the behest of Tweed.

In 1873 after Tweed was removed from power, Governor John A. Dix granted approval for Beach’s expansion proposal. The scope of the project was wide. The original charter of the Beach Pneumatic Transit Company, from 1868 (but printed in 1873) called for “pneumatic tubes beneath the streets, squares, avenues and public spaces of the cities of New York and Brooklyn, and under the bed of the waters of the North River, from the city of New York to the shore of New Jersey.” The system would carry both transit lines and “packages, mails, merchandise and property,” and the charter also allowed for the construction of “suitable ornamental lamp-post boxes, pillars, or receptacles, not exceeding thirty inches in diameter, connected with said pneumatic tubes, for the deposit of letters, parcels, and property to be transmitted there-in.”

Unfortunately, the project came to a halt due to the disastrous Panic of 1873. The tunnel entrance was shut down after the project closed, and the station, built in the Rogers Peet Building, was reclaimed for other purposes before being destroyed in an 1898 fire.

Underground NYC Subway Tour

Ride through the oldest stations, uncover hidden art, and more!

Although New Yorkers loved the subway, many people doubted its practicality on a larger scale, since a rather extensive subway system of pneumatic tubes had never been developed before. Due to the rise of electric locomotives, a pneumatic system never came to fruition, and it took over 25 years for people to begin discussing the return of this style of subway after investors initially pulled funding from the project. Despite the subway project’s failure, the American Pneumatic Service Company began operating a 27-mile pneumatic tube mail system between 22 post officers in New York City in 1897, which had been proposed in the original plan. That system was in operation, in part, until 1953.

In 1912, construction workers found the remains of the subway car, the tunneling shield, and the grand piano while excavating the BMT Broadway Line. The original shield at the south end of the tunnel was donated to Cornell University, although it has since been lost. It is believed that the tunnel was completely destroyed during construction of the BMT line. A plaque that contains Beach’s name was placed in the City Hall station by the New York-Historical Society.

Next, check out The Top 20 Secrets of the NYC Subway!