Black Friday Sale 🎊

Explore overlooked city sights on one of our expert-led NYC walking tours!

Walking through Grand Central Terminal, we see years of New York City’s culture, from ornate art to iconic bars and restaurants. Throughout the pandemic, Grand Central Terminal has been an accessible repository of great art. With works by some of the world’s most famous artists and sculptures that have defined midtown Manhattan (along with a long-forgotten school of art), Grand Central Terminal is an art museum in itself. Here is our guide to the art and art history of Grand Central Terminal (and if you’re looking for more secrets, take our virtual tour of Grand Central!)

Created by American sculptor Donald Lipski, Sirshasana is a sculptural chandelier shaped like a golden-rooted olive tree. The sculpture is suspended above the 43rd Street entrance to the Grand Central Market and features over 5,000 crystal pendants. The sculpture draws from Hindu and Greek tradition and takes its title from a yoga headstand position called the inverted tree. Given the exotic and diverse options at the market, the sculpture illuminates the marketplace that so many people walk through daily.

“The space was designed so that morning sun bathes the tree and floods the market with light,” MTA Arts and Design wrote. “The form has writhing, enticing, and unexpected elements, with the base of the tree finished in gold and crystals dangling in place of olives.”

At the Station Master’s Office is a 1997 mural by Roberto Juarez titled A Field of Wild Flowers that depicts a lush garden landscape with all sorts of colorful flora. Supposedly, the work was designed to appear like a train passenger was looking out the windows of a slow-moving train.

Using artistic materials like urethane, varnish, and gesso, as well as rice paper and peat moss, the work has a variety of textures to add to the mural’s authenticity. The work also mimics some of the Terminal’s architectural features, such as details of fruit, acorns, and garlands.

Underneath the Graybar Building sits the Graybar Passage Mural, painted in 1927 by Edward Trumbull, who also painted a mural on the Chrysler Building‘s ceiling. Trumbull also served as “colortone director” of the Rockefeller Center and also painted murals for the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company Building. Many of the mural’s extravagant colors have since faded, leaving a caramel color.

The mural features significant technology like a train pulled by an electric locomotive as well as several airplanes, including the Spirit of St. Louis flown by Charles Lindbergh. A bridge resembling the city’s High Bridge and the construction of a skyscraper can also be seen in the mural as representations of the city’s development.

Looking up at Grand Central’s Main Concourse’s ceiling has been compared to looking up into a starry sky, as the mural contains over 2500 stars against a turquoise background. Originally executed in 1913, the mural was a collaboration between architect Whitney Warren, of Warren & Wetmore, the Terminal’s architects; French artist Paul Helleu; muralist J. Monroe Hewlett; painter Charles Basing of Brooklyn’s Hewlett-Basing Studio; and astronomer Dr. Harold Jacoby of Columbia University. The ceiling was heavily based on the Uranometria, a 1603 star atlas by Johann Beyer. Many constellations like Aquarius, Cancer, and Orion can be seen on the ceiling today, yet the story of the ceiling’s construction is amusing in itself.

Although based on a star atlas, the original mural was actually painted backward, with west being east and vice versa. According to Dr. Jacoby, the star diagram was meant to be held overhead, yet the painters must have laid it on the floor instead. Cornelius Vanderbilt himself rewrote history when the error was discovered, claiming it was how it was intended as if man was looking down from the gods.

Although the overall arrangement of the constellations is reversed, the constellation Orion is actually the only correctly rendered one since Orion faces the opposite way as he should have faced. Adjacent constellations Taurus and Gemini are reversed because the mural was painted backward, but they are also reversed in their relation to Orion, as Taurus is depicted near Orion’s raised arm where Gemini should be. Surprisingly, Bayer was the one who reversed Orion 300 years earlier, perhaps to show the celestial hunter fighting the bull.

Eleven years after the mural was completed, the roof leaked and damaged the mural, which then “faded to a hue something like that of a khaki shirt overdosed with Navy blue.” In order to fix the mural, cement-and-asbestos boards covered the ceiling, and an entirely new mural was painted, this time with less astronomical detail. The ceiling boards were repainted in 1996 after years of general air pollution, car emissions, and to a lesser extent, cigarette and cigar smoke. The mural also contains a small dark circle above Pisces that was cut to allow a cable to lift an American Redstone missile, placed to improve public morale after the launching of Sputnik in 1957.

Guastavino Tiles, constructed by the Guastavino Company of father-son Spanish immigrants, appear all throughout the city and in a number of locations in Grand Central Terminal. On the lower level at the Oyster Bar & Restaurant, Guastavino Tiles adorn the eatery’s interior in a herringbone pattern, with lights running up and across the grand vaults. Since 1913, the restaurant has been serving oysters and seafood dishes to locals and tourists alike.

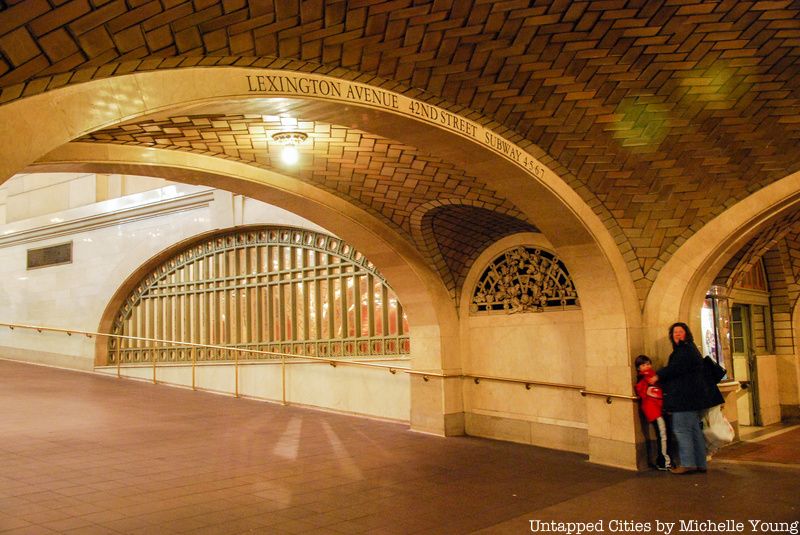

Just in front of the Oyster Bar, the Whispering Gallery provides amusement for passersby, as the acoustic pockets of the Guastavino-tiled vaults allow for messages to be heard clearly by people standing at opposite diagonals of the base. The way the gallery was built makes it seem as though people are standing right next to each other.

Another interesting spot you can find on the lower level of Grand Central Terminal is the Metro-North lost and found facility. This space, full of lost AirPods, umbrellas, gloves, and a few more unique finds, is where every item left on Metro-North ends up, whether it was lost on a train in the Hudson Valley or a station in Connecticut.

The murals inside the Central Cellar wine store in Grand Central, next to Track 17, were rediscovered during the restoration of the terminal in the 1990s. They were once part of the movie theater Grand Central Theatre, which opened in the 1930s, playing shorts, cartoons, and news reels.

The first film to screen at the theater was the MGM film Servant of the People: The Story of the Constitution of the United States. According to the website, I Ride the Harlem Line, the theater was advertised as the “most intimate theatre in America” and was open every day until midnight. Another fun tidbit is that the theater was designed by Tony Sarg, the same person who created the first balloons for Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade, including Felix the Cat!

The sculpture Glory of Commerce, alternatively named Transportation or Progress with Mental and Physical Force, adorns the front of Grand Central Station. Designed by French sculptor Jules-Félix Coutan, the work is an astonishing 48 feet tall and 66 feet wide and portrays the terminal as a groundbreaking step towards technological innovation in the city. At the center stands Mercury, representing travel and commerce, standing in a contrapposto pose in front of an eagle. To Mercury’s left is Vulcan holding a hammer (though he is often mistaken as Hercules) sitting among an anchor, beehive, and grapes. To Mercury’s left is Minerva, the goddess of wisdom, looking at a roll of parchment while sitting among a globe and a compass.

Coutan supposedly never stepped foot in the United States, creating the model in Paris and thereafter shipping it to the United States. The sculpture also sits above a 13-foot-wide Tiffany clock, the world’s largest example of Tiffany glass. The sculpture also represents the Vanderbilt family, as William K. Vanderbilt was a long-time owner of the New York Central Railroad.

Grand Central is home to two cast-iron eagle sculptures, one below the Glory of Commerce sculpture and the other above Grand Central Market. Each weighs about 4,000 pounds and has a 13-foot wingspan. Prior to the construction of Grand Central Terminal, there were about a dozen eagle sculptures, but after the original Grand Central Station was demolished, some of the eagles were transferred to other locations across the state.

The eagles that stand at the Terminal today were dispersed to Bronxville, Westchester, and Garrison, Putnam County before being returned to Grand Central. Other eagles are currently at places like a private home in Kings Point, Nassau County, a train station in Sleepy Hollow, Westchester, and Long Island‘s Vanderbilt Museum. Today, the two at Grand Central help to keep pigeons away with their fearsome expressions while also revealing to passersby the United States national emblem representing freedom.

Also inspired by Vanderbilt is his namesake statue on the Terminal’s south facade, sculpted by Ernst Plassmann, who also famously sculpted Benjamin Franklin and Chief Tammany. The statue, which stands at 8.5 feet tall, depicts Vanderbilt in a fur-trimmed overcoat with one hand on his chest and the other outstretched. A 1929 New York Times article notes that it was “the largest bronze figure ever made in this country.”

Unveiled in November 1869, Plassman’s original Vanderbilt statue was criticized as glorifying Vanderbilt while ignoring the many people killed in New York Central’s railyards. The statue was originally created for the facade of the Hudson River Railroad Depot in what is now Tribeca. After moving to Grand Central in 1929, the sculpture continued to receive criticism for its propagandist nature, but it still stands there today as a testament to Vanderbilt’s contributions to the railroad industry.

In 2000, artist Jackie Ferrara created Grand Central: Arches, Towers, Pyramids, a series of ceramic mosaics on a number of passageways and waiting areas in Grand Central.

The mosaic’s simplicity, repetitiveness, and mathematical nature make it seems like “images on a strip of film, or a line of faces framed in the windows of a passing train,” according to Ferrara. As passengers walk along the platforms, the images shift to reveal an almost meditative atmosphere, with no two images being the same.

With a similar theme to the Main Concourse Ceiling, Ellen Driscoll’s As Above, So Below, made of glass, bronze, and mosaic in the Grand Central North passageway, depicts scenes from the night sky. Her artwork portrays images of myths, civilization, heavens, and the underworld and features a diverse cast of people from many different backgrounds, some taking on characteristics of mythical figures.

While many of us are in a hurry, the artwork depicts our connection to the heavens and the wider world through various colors, tales of the past, the sun and stars, and the fates and fortunes of deities and humans.

Using Aluminum sheets, steel wheels, and brass disks, Dan Sinclair’s Fast Track and Speedwheels is situated in the passageway between the S shuttle and the 4, 5, and 6 lines. The sculptures depict imagery of fast train travel through its spinning gears and pistons. The sculpture also draws from Art Deco shapes and design while revealing a rather futuristic scene.

“I want my sculpture to make people think of the power of the engines that drive the trains, the speed and efficiency of them . . . the sculptures also reflect the architectural elements of Times Square and the Art Deco glamour of Radio City Music Hall,” Sinclair told the MTA.

The Grand Central Art Galleries and School of Art in 1923. Image in public domain from the 1923 opening exhibition catalog, from the New York Art Resources Consortium and contributed by the Frick Art Reference Library.

Thanks to a starring role in the bestselling novel The Masterpiece by Fiona Davis, the lost Grand Central School of Art has returned to the limelight. Between 1923 and 1944, the painters Edmund Greacen, Walter Leighton Clark, and John Singer Sargent founded and ran the Grand Central School of Art, occupying the sixth floor of the terminal’s east wing. Alongside these artists, Daniel Chester French, who designed the statue of Abraham Lincoln at the Lincoln Memorial, directed the school. In its first year, the school had over 400 students, and at its peak, it became one of the largest art schools in New York with 900 students.

According to a 1924 New York Times article, figures such as costume designer Helen Dryden (supposedly the highest-paid woman artist in the United States in the 1930s), sculptor Chester Beach, a muralist Dean Cornwell were among the school’s instructors. Arshile Gorky, an Armenian-American painter behind works like The Liver is the Cock’s Comb, joined as an instructor a few years later. Painter Harvey Dunn, best known for his painting The Prairie is My Garden, also became an instructor. The school also held summer sessions in Maine but closed in 1944 after 20 years of educating artists who would go on to win major awards like Willem de Kooning.

The Grand Central Art Galleries and School of Art in 1923. Image in public domain from the 1923 opening exhibition catalog, from the New York Art Resources Consortium and contributed by the Frick Art Reference Library.

Before opening the Grand Central School of Art, Clark, Sargent, and Greacen established a nonprofit called the Painters and Sculptors Gallery Association, and the nonprofit held its exhibition and administrative locations at the Grand Central Art Galleries on the sixth floor of the Terminal. From 1923 to 1994, the galleries displayed works of Sargent, William Hogarth, James Whistler, and many other artists throughout the decades. In order to become members of the gallery, artists would have to give a work of art each year for three years, and non-artists would have to give around $600 to purchase a donated work.

The opening gala attracted over 5,000 people and featured art by a number of artists like Sargent, French, and Gutzon Borglum, who designed Mount Rushmore. Paintings ranged in price from $100 to $10,000, and in the first ten years, sales reached $4 million. After much success in Grand Central Terminal, the nonprofit moved offices to the second floor of the Biltmore Hotel.

Among the galleries’ greatest achievements was the design and construction of the United States Pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 1930, featuring about 90 paintings and 12 sculptures. The pavilion was run until the 1950s, and museums like the Whitney Museum of American Art and the Museum of Modern Art presented exhibitions there. Famous exhibitions at the Grand Central Terminal included “Retrospective Edition of British Paintings,” featuring the art of William Hogarth, Joshua Reynolds, and Thomas Gainsborough. After Sargent’s death, the Galleries organized a posthumous exhibition of his sketches and unseen works, which included sketches of his Madame X and Gassed. Other famous exhibitions included one featuring sculptures of Malvina Hoffman, one featuring Italian art by figures like Amedeo Modigliani, and one titled “Realism From the People’s Republic of China.”

Photograph by Filip Wolak from the Changing Signs, Changing Times: History of Wayfinding in Transit Exhibition by the New York Transit Museum

Although most of the artworks featured in past exhibits are not currently at Grand Central, there were a number of special exhibitions and interactive art installations that offered passengers with fascinating experiences on their daily commutes. In 1948, Filene’s held a fashion show on the balcony of the Main Concourse, and supposedly over a thousand square feet of sand was imported for the fashion show.

French artist Christian Boltanski displayed over 5,000 personal belongings from the terminal’s lost-and-found, which he displayed on metal shelves. And in 2009, four BMW Art Cars were displayed at the terminal, painted by famous artists Andy Warhol, Frank Stella, Roy Lichtenstein, and Robert Rauschenberg respectively. In addition, the New York Transit Museum has regular exhibitions inside the gallery they have in Grand Central.

Next, take our virtual tour of Grand Central!

Subscribe to our newsletter