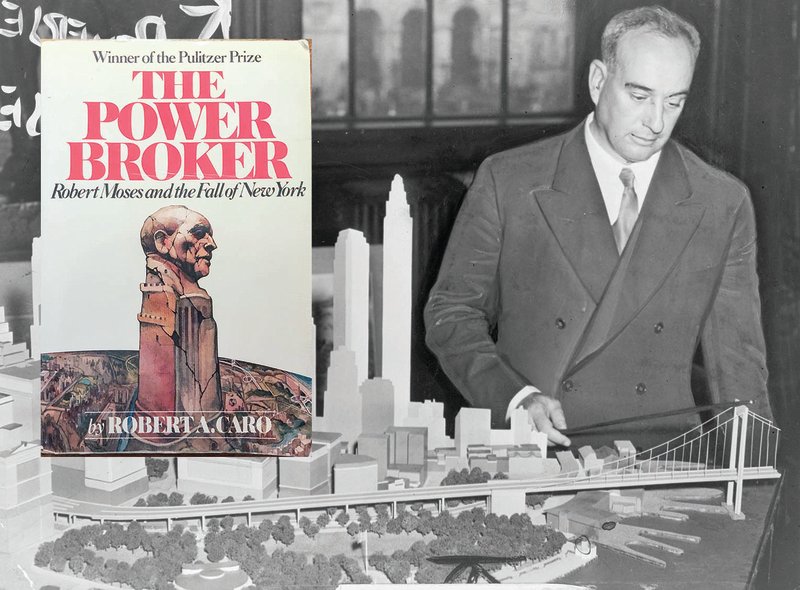

Background photograph from Library of Congress. Book cover photographed by Untapped New York.

Background photograph from Library of Congress. Book cover photographed by Untapped New York.

The Power Broker, a 1,246 page biography about “master builder” Robert Moses is in the news with the New York Times reporting on all the television interviews the book has appeared in the background during this pandemic. In recent years, Robert Moses has been the subject of numerous cultural productions — a rock musical called BLDZR: The Gospel According to Robert Moses and an opera, and as a character in Motherless Brooklyn (disguised, thinly, as Moses Randolph).

Moses remains a controversial figure, more hated today than loved, often representing the type of urban planning theories that are derided today. His plans to build an expressway through Soho and Little Italy were nixed, but he did manage to get in the Cross-Bronx Expressway, the Sheridan Expressway, the Belt Parkway and more — slicing through neighborhoods or filling in marshland with trash to create more land for highways. Yet there are many things New Yorkers still benefit from that were implemented by Moses: he added more than 22,000 acres of city parkland, built the city’s public pools, brought the United Nations to New York, and more.

The Cross-Bronx Expressway

The Cross-Bronx Expressway

It’s important to remember that public opinion was quite different earlier when Moses was operating particularly in the earlier portion of his tenure. Caro covers this well in The Power Broker, recounting the rose-colored words used in the news to describe Moses’ projects in his time, including something mundane to us today like the West Side Highway (deemed a “masterpiece” with a “beauty” that was “intoxicating”).

A glowing 1939 article in The Atlantic opens with a truck driver telling his appreciation of Moses’ work on the city’s parks: “This spontaneous tribute is indicative of the growing appreciation of millions of New Yorkers of all ages and classes for the man who, in less than five years, has remade or refurbished a considerable portion of the metropolis. The Commissioner of Parks under Mayor La Guardia’s Fusion administration is also head of the magnificent park system of New York State, which he conceived and largely created.” It goes on and on, calling Moses “the most farsighted and constructive of public spenders,” and that he demonstrates “in brilliant fashion that democracy can be made to work by skillful, resolute handling, and that ‘public improvements’ can be given a surprising amount of beauty.”

A strapping Robert Moses in 1938. (Images via Library of Congress and The Metropolitan Transportation Authority Bridges and Tunnels Special Archives).

A strapping Robert Moses in 1938. (Images via Library of Congress and The Metropolitan Transportation Authority Bridges and Tunnels Special Archives).

Of course, Moses was able to achieve a lot, good and bad, because of his long reign. Moses held onto seemingly unchallenged power in New York for over four decades, through the administrations of 6 mayors, 5 governors, and several presidents. Never elected to office, he was appointed to many positions including a time when he held twelve titles concurrently. These positions included New York City Parks Commissioner, Commissioner of the New York City Planning Commission, Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority, President of the New York World’s Fair, New York State Power Authority Chairman President of the, Long Island State Park Commission, and Chairman of the New York State Council of Parks.

How did Moses stay in power for so long? The lowly tollbooth gave Moses a never-ending cash flow that was used as collateral for the bond issues he needed to finance his projects, plus federally subsidized financing for three decades of public works kept the money flowing. He also stealthily rewrote the New York State legislation governing public authorities while he was New York State Governor Al Smith’s chief of staff in the 1920s, laying the groundwork for his consolidation of power later.

You can see the many projects Moses is hated for and appreciated for in our previous coverage, but today we are sharing some of his personal haunts from where he lived, worked, spent time, and where he remains for eternity. We’ve combed through The Power Broker as well as other sources to put together this brief picture of Moses’ intense and long life.

1. Robert Moses’ Apartments

Moses was born and raised in New Haven, Connecticut near Yale University. At the age of nine, his family moved to Manhattan, first living in a townhouse off Fifth Avenue on East 46th Street. As a college student at Yale, Moses would stay with his parents in a rented apartment on Central Park West and 70th Street on visits to New York. According to City Journal, in the early 1930s, Robert Moses lived on Riverside Drive with a view of the massive construction project that would cover the New York Central Rail tracks (now Amtrak) and become a park extension of Riverside Park. (However, we have not been able to corroborate a Riverside Drive residence yet. Caro mentions in The Power Broker however that during this period, Moses lived in a doorman building on Central Park West and would take a cab from City Hall to Riverside Drive on his way home).

In 1939, Moses moved to the Upper East Side. The Atlantic article states, “With their two daughters, [Robert Moses and his wife] live in an apartment on the Upper East Side, overlooking the river, the island parks, and Triborough Bridge.” Caro indicates in The Power Broker that in 1939, Moses was already living on Gracie Terrace. The Atlantic also mentions a house in Babylon, Long Island, taking care to mention that it was simple and old, to reinforce that “Moses’s inheritance helps him to live comfortably, but he is not wealthy, as is commonly supposed, and public service has involved many family sacrifices.” (Clearly this was a “sponsored article” before there was such a thing!

From at least the 1970s to his death, Moses lived at 1 Gracie Terrace, off of East End Avenue on a dead end street that leads out onto the promenade. It’s just a few blocks south of Carl Schurz Park where Gracie Mansion is located. In 2017, the co-op was listed for sale at $1.9 million.