The Berkshires Bowling Alley that Inspired "The Big Lebowski"

It’s been 36 years since the release of The Big Lebowski, the irreverent cult comedy by Joel and Ethan

Raised in Canarsie, Brooklyn, Charles ‘Charlie’ H. Cochrane, Jr. was someone who always did things by the book. He was methodical, acted with care, intention, and precision, and had a humility about him that forced him to admit when he made a mistake or could have done more. He was a proud cop, whose uniform always looked tidy. His patrolman’s hat sat atop a head of thick brown hair, even if the hairstyle was dated and from decades earlier. Others who knew him remarked that Charlie scoffed at spending money on himself to keep up with trends. He had a button nose, eyes that sat narrow near it and two front teeth that dominated a small, expressive mouth that was often smiling. Evidence of this was shown in the laugh lines that held his smile like two large parentheses.

Two years before the 1969 Stonewall uprising put a fist in the air to mark the start of a modern movement and fight for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT, today LGBTQ+) rights in New York City and elsewhere, Charlie Cochrane joined the New York City Police force.

One of New York City’s finest, Cochrane knew the truth he carried once spoken could lead to banishment and physical harm. He’d be on the force for a decade before he came out to anyone. The first person he told was his partner in 1977. Yet, if real change was to be made within the New York Police Department (NYPD) for Cochrane and all gay officers, he couldn’t stop there. And he wouldn’t.

It was the early 1980s, kids watched “The Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles” and “He-Man” cartoons, Donkey Kong was a popular videogame, and kids toted around Cabbage Patch Kids. Ronald Reagan was president, MTV started showing music videos, and only music videos, and a man by the name of Ted Turner started the first 24-hour news channel, CNN.

What did they cover to fill all those news hours? An epidemic that was taking the lives of hundreds of people, mainly in the gay community. And unfortunate misinformation was also circulating that had gay people looking as untouchables. A New York City doctor treating patients with the “rare lung infection” that became known as AIDS would face eviction from his apartment building for his good works.

On Friday, November 20, 1981, during a New York City council hearing on a gay rights bill proposed to ban discrimination due to sexual orientation, Sergeant Cochrane would make his boldest move yet. During his testimony he came out as gay publicly and in doing so established himself as the NYPD’s first openly gay cop since the force’s founding in 1854. More than a week before the hearing, in the Brooklyn home they shared, Cochrane came out privately to his family.

Even after Cochrane’s testimony before the City Council, cops who came out as gay could face discrimination—including death threats—while on the job. A gay rights bill to secure basic civil rights for members of the gay community for which Cochrane testified wouldn’t find passage until 1986, five years following Cochrane’s testimony for a similar bill, and 15 years following the first proposal of such legislation.

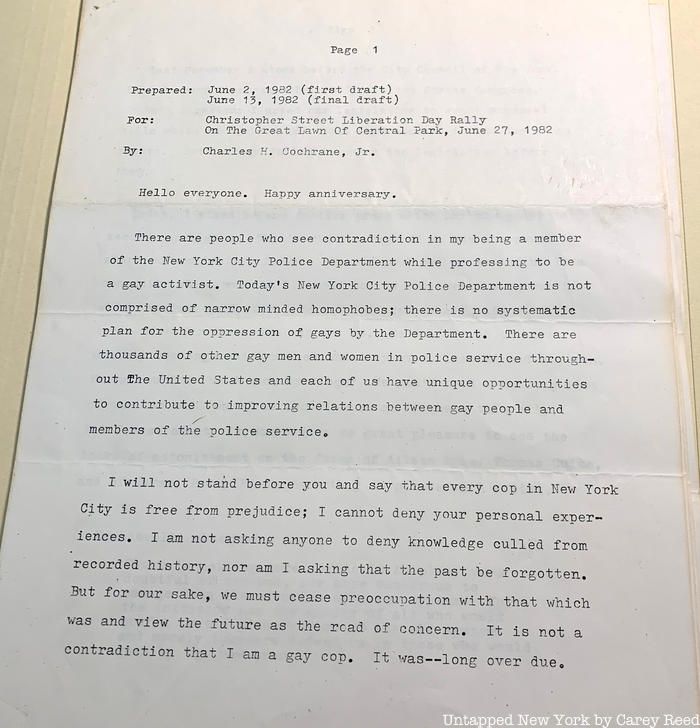

Archival items from the Gay Officers Action League records. Manuscripts and Archives Division. The New York Public Library. Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations.

Archival items from the Gay Officers Action League records. Manuscripts and Archives Division. The New York Public Library. Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations.

Throughout the 1980s, threats would come to gay officers on and off duty. There in the basement behind the red door of the New York City’s oldest Roman Catholic Church building, ten men joined Sergeant Cochrane in a secret, first-of-its-kind meeting. When Cochrane arrived, he informed his fellow officers that he’d received a bomb threat about the meeting on his answering machine. That did not move the men. And the first meeting of what would become the Gay Officers Action League (GOAL) began.

In June of 1982, as GOAL fought for legitimacy within the NYPD and eight months after Cochrane had come out publicly, members of the Gay Officers Action League marched for the first time in the annual Christopher Street Liberation Day march—what we know today as the Gay Pride Parade. The march and rally marked the anniversary of the 1969 Stonewall Riots, which erupted at a gay bar in Greenwich Village following a police raid and the arrests of gay patrons. GOAL Founder and President Charlie Cochrane would speak at the march’s gay-in and rally on the Great Lawn in Central Park.

Archival items from the Gay Officers Action League records. Manuscripts and Archives Division. The New York Public Library. Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations.

“If others will not give us power; if we cannot seize power; then we must create our own power,” Cochrane told the crowd. Always being one to play by the book, he added: “Let us enter into a lawful conspiracy which seeks to purge from society those who are bent on our destruction.”

Three months later, the Gay Officers Action League would send out its first formal communication to active and retired officers to recruit more members. It wouldn’t come as a surprise but was still disheartening when other fraternal organizations within the Police Department worked to block GOAL from being acknowledged as legitimate, a year after its official formation. Cochrane would often harken back to the events of the Stonewall Riots and use the word “stone walled” stealthily in communications when talking about the pushback within the police force to formally establishing GOAL as a special professional, fraternal organization for gay officers.

GOAL members continued on, making fliers and creating a logo that incorporated the NYPD shield often paired with the gay pride rainbow flag. They printed up membership cards that entitled the bearer to lifetime membership. It’d be a year before the group printed up 200 copies of its first newsletter for distribution and Andy Warhol would snap a photo of GOAL members marching in NYC’s Gay Pride parade.

Photo: Edwin J. Torres/Mayoral Photo Office.

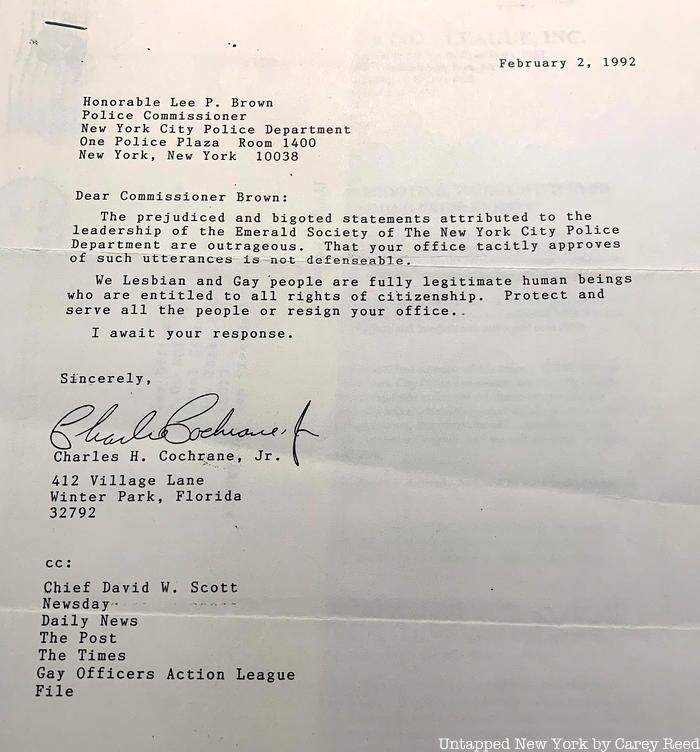

Cochrane even continued to fight after retirement in the late 1980s from Florida. When the Emerald Society, a group that had a chapter in the NYPD sent out a communication about a unanimous vote to ban gay and lesbian individuals from participating in the 1991 St. Patrick’s Day Parade in New York City, he sent off a letter to the Police Commissioner Lee P. Brown and the press: “We lesbian and gay people are fully legitimate human beings who are entitled to all rights of citizenship. Protect and serve all the people or resign your office.” In 2000, because of bans on allowing members of the gay and lesbian community to march in the city’s parade that continued over the years, a new parade, St. Pat’s for All, was established in Queens. Another 14 years would pass before New York City’s premiere St. Patrick’s Day parade permanently dropped its ban—Staten Island continues to host a parade that does not allow members of the LGBT community to participate.

Archival items from the Gay Officers Action League records. Manuscripts and Archives Division. The New York Public Library. Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations.

Today, not only are NYPD officers involved in GOAL, but there are chapters throughout the U.S. in New England, Philadelphia, and Chicago. Each year, a Charles H. Cochrane Award is given out at the annual GOAL gala. 2017’s recipient was Brooke Bukowski, the first transgender officer in the NYPD. “Thank you for being who you are and for not being afraid to be that person in the department,” Bukowski said of Cochrane. Cochrane was not there to witness this milestone, one that came more than three decades after the first secret meetings of GOAL in the church basement in the 1980s. He died of cancer in Florida in 2008.

In 2016, at Washington Place and 6th Avenue in Greenwich Village, on the block of St. Joseph’s Church, a green sign was erected, reading: Charles H. Cochrane Way. Located less than a five-minute walk from The Stonewall Inn, it’s a permanent place from which Cochrane continues to serve and protect all New Yorkers. Current GOAL President Brian E. Downey said “What I’d tell Charlie Cochrane? ‘Never met me before, but you saved my life, and you did it for a lot of other people.’”

Join us today at noon for a virtual poetic walking tour of Walt Whitman’s Queer New York tracing his haunts in Greenwich Village.

Subscribe to our newsletter