At the close of Prohibition, Seagram’s from Canada was well-positioned to export its spirits to the United States. In fact, during Prohibition, the Bronfman family which owned Seagram’s was stockpiling alcohol to be ready when America went wet again. By 1933, when the 18th Amendment was repealed, Seagram’s owned the “largest private stock of aged whisky” in the world. Even during Prohibition, Seagram’s was selling liquor to the United States, first directly to bootleggers and then when export was banned in Canada, the company shipped stock to the French island territory of Saint Pierre and Miquelon near Newfoundland and smuggled it to the States.

With his smart marketing schemes, Samuel Bronfman nearly singlehandedly rebranded whiskey from the domain of bootleggers to that of the refined class. A 1934 Seagram’s advertising campaign had the tagline, “We who make whiskey say: drink moderately.” Lisa Jacobsen writes, in an article for the journal Social History of Alcohol and Drugs, “If alcohol producers were to make repeal success, they would not only have to teach consumers what commercial-grade alcohol should taste like, smell like, look like, and feel like going down, but they would also have to teach Americans the etiquette (and imperative) of responsible drinking. Alcohol producers in essence had to cultivate new kinds of consumer knowledge to advance the cultural and political legitimacy of their still morally suspect industry and products.” In essence, the marketing efforts associated alcohol “moderation with masculine virtue, middle-class respectability,” says Jacobsen, values which persist today.

Chrysler Building in 1932. Photo by Samuel H. Gottscho, in public domain

Chrysler Building in 1932. Photo by Samuel H. Gottscho, in public domain

As such, Seagram’s rented a floor high up in the Chrysler Building in Manhattan, the icon of modernity and respectability as skyscrapers went at the time, as part of their efforts to take over the American alcohol market. The company hired architect Morris Lapidus to create an office with a private executive bar. In his early career, Lapidus had worked for Warren and Wetmore, the architectural firm that designed Grand Central Terminal, and later became a retail design expert while working for Ross-Frankel. Lapidus may be most famous for his later career work defining the hotels in Miami, designing The Fountainbleu Hotel (which had a starring role in the most recent season of The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel), and the Eden Roc Hotel.

But 1933 was the year Lapidus was hired by the Seagram Company. The office was designed in an “exuberant, bright and shiny deco-moderne style” that defined Seagram’s embrace of modern architecture as a form of civic duty,” writes Benjamin Flowers in Skyscraper>The Politics and Power of Building New York City in the Twentieth Century.

The Executive Bar at the Seagram’s office in the Chrysler Building in 1939. Photo by Otto Schlesinger from Library of Congress.

The Executive Bar at the Seagram’s office in the Chrysler Building in 1939. Photo by Otto Schlesinger from Library of Congress.

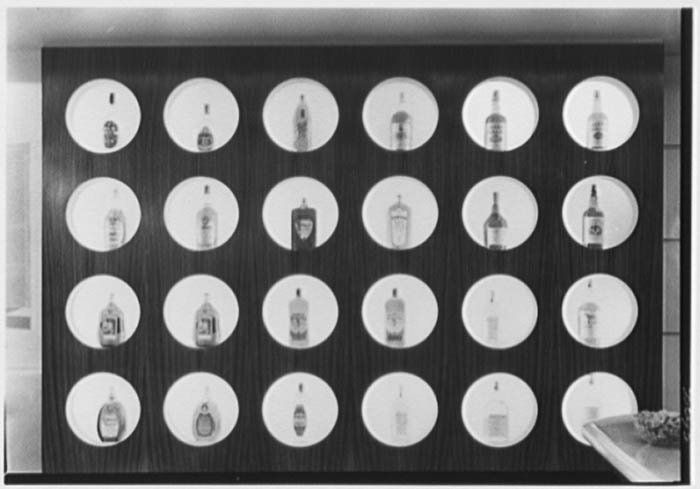

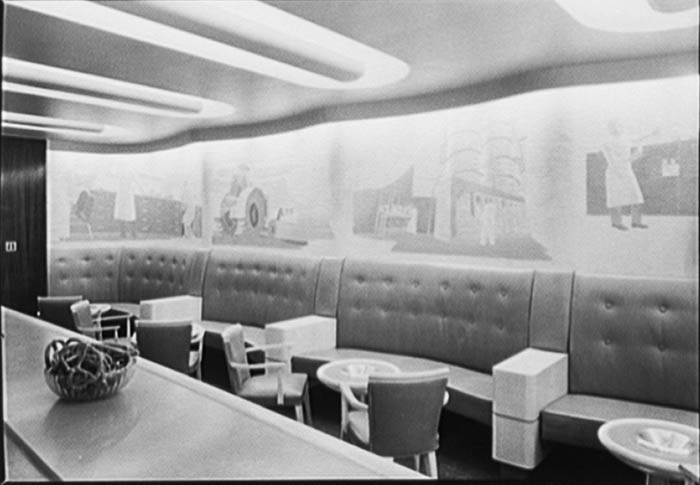

The design of the Executive Bar clearly takes cues from Lapidus’ retail design aesthetic, with curved lines throughout in the ceiling, along the bar, and following the leather banquettes. In the book Cafes and Bars: The Architecture of Public Display the bar is described as a “showroom of and for [Seagram’s] own products: bottles of alcohol” displayed in round display holes and notes that instead of being public facing, the bar was “hidden away in the heart of a skyscraper.” According to a 1956 report in Forbes, reporters would be “summoned” there for news and would sample the latest in the extensive range of Seagram’s products.

Photo by Otto Schlesinger from Library of Congress.

Photo by Otto Schlesinger from Library of Congress.

A very detailed description of the space in Cafes and Bars offers additional detail that accompanies the photographs by Otto Schlesinger (available at the Library of Congress). The walls, the report describes, “are covered in panels of bleached rift-sawn oak and East Indian rosewood and North American plywood, combined with brown rubber tiles for the floor and leather for settees along the wall…the murals above the banquettes by Stuyvesant van Veen depict the production and tasting of spirits…” Fluorescent lighting, curved of course, illuminated the bar. A mirror behind the bar expands the space and duplicates the alcohol display on the back wall as well as the bottles at the bar.

Photo by Otto Schlesinger from Library of Congress.

Photo by Otto Schlesinger from Library of Congress.

The Seagram company would eventually build its own skyscraper in New York City 1958, the Seagram Building on Park Avenue designed by Mies van der Rohe with interiors by Philip Johnson. The glass curtain-wall building would host the iconic Four Seasons Restaurant, the premiere destination for power lunches in New York City and the building would become a landmark in its own right.

Photo by Otto Schlesinger from Library of Congress.

Photo by Otto Schlesinger from Library of Congress.

The Executive Bar in the Chrysler Building is long gone, much like the other Art Deco and Art Moderne spots in the building like the auto showroom on the ground floor and the Cloud Club at the top. But to get a sense of the powerhouse that Seagram’s has been, it controlled the distribution (and in some cases also the production) of brands like Dewar’s, Captain Morgan, Chivas Regal, Crown Royal, Seagram’s V.O., Tropicana, Absolut Vodka, and more.

By the 1950s, the company was diversifying and going into oil and coal, and in the 1980s as a result of acquisitions, Seagram’s became the largest shareholder of DuPont, the chemical company. In the 1990s, Seagram’s got into the entertainment business, investing in Time Warner and MCA (which includes Universal Studios). In 2000, Seagram’s merged with Vivendi, although the new French company soon sold off the liquor business to Pernod Ricard and Diageo. Over time the Bronfman family sold their shares of Vivendi ending the family’s long history with Seagram’s from Prohibition to the 21st century.

Next, check out the Top 10 Secrets of the Chrysler Building and the Secrets of the Seagram’s Building.