Central Park trees include nine of New York City’s so-called “Great Trees.” In 1985, New York City embarked on a “Great Tree Search,” seeking nominations from ordinary citizens for trees of unusual size, form, species, or historical association. Of the millions of trees across the five boroughs, 65 were chosen as the Great Trees of New York City. There are 19 in the Bronx, 13 in Brooklyn, 9 in Queens, 10 in Staten Island, and 14 in Manhattan—9 of which are right in Central Park (a 10th, the Evodia near Heckscher Playground, appears to have been removed).

Visiting these Central Park trees feels like participating in a piece of community history, and you’ll get a great walking tour of the park along the way. We started at the south end at the Mall and worked our way up, though you could just as easily start at the Reservoir and walk down.

1. Grove of American Elms (Central Park Mall)

The largest grove of American elms in the world canopies Central Park’s Literary Walk, creating a stippled stained-glass effect overhead. This is one of two groves on the Great Trees list, and standing in its midst, you can see why it would be impossible to pick a single tree. The evenly-spaced trunks, sinuous branches, and dappled light make for a space that is both lively and serene—many say cathedral-like.

The elms stand tall (some over 90 feet) thanks to vigorous efforts on the part of the Central Park Conservancy. In the 1930s, Dutch elm disease entered the United States in a shipment of imported furniture, and quickly spread throughout the city. By the 1980s, the Park was losing as many as 100 elms per year. Today, that rate is much lower (though a bad year can still claim as many as 35). The elms on the Mall are inspected regularly, and when one elm must come down, a new one is planted in its place. An added bonus at the grove of American elms: the Women’s Rights Pioneers Monument, newly unveiled on Literary Walk.

2 & 3. Elms on the Rocks (Rocky Outcrop East of the Mall)

Once you’ve walked through the Mall, find the path that runs alongside it to the east. About midway up, you’ll stumble upon a pair of elms that look like something out of Grimm’s Fairy Tales. These two trees, which appear as one but are classified as two on the Great Trees list, seem to grow out of the bedrock, spreading over it so you can’t tell where rock ends and tree begins.

Although Central Park is man-made, its rocks are not. The rock you see is exposed portions of ancient bedrock, shaped by ice 190 million to 1.1 billion years ago. This scene—the heavy, ancient rocks, the thick trunks of the elms almost engulfing them—feels like a glimpse into the Park’s wilderness past.

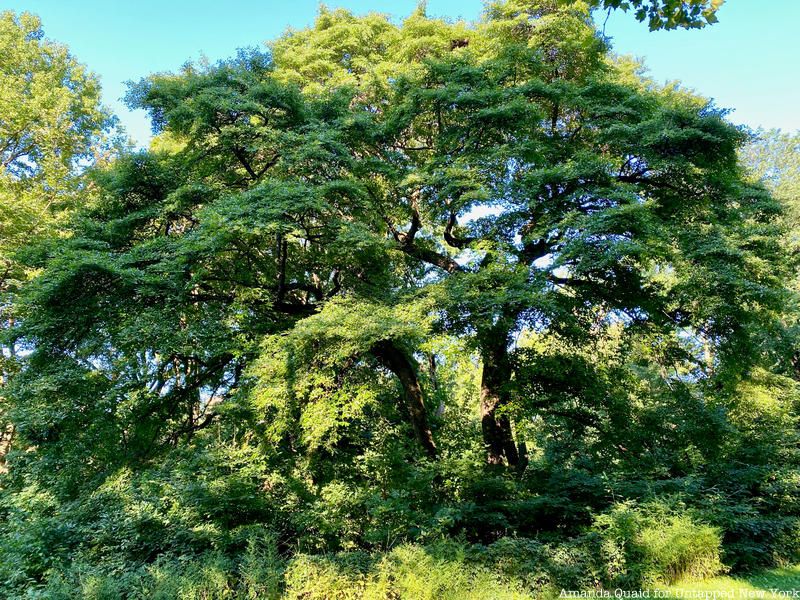

4. Black Tupelo (Center of the Ramble)

Of the 18,000 trees in Central Park, only 150 date back to its creation in 1857. One of those is the Black Tupelo that graces the center of the Ramble. To find it, enter at the Ramble’s northwest entrance and walk straight. The Tupelo Meadow will be on your right, about halfway across. In summer, when its leaves are green, it’s difficult to distinguish the tree’s shrub-like silhouette from its surroundings. In fall, however, tupelos turn bright red—you’ll be sure to see it.

At first glance, the 81.18 foot-tall tree appears lush and bushy. But walk around to the back, and you’ll see the three trunks and limbs completely exposed—like gnarly knuckles reaching toward the sky. These two faces are its most distinctive quality for us. Edward Sibley Barnard, co-author of an exhaustive map of the Park’s trees, is most enchanted by its age. “Old trees have a sacred element for me,” he says. “They created us. We’re all mammals that spent our time in the canopy.”

5. American Elm (77th Street & Central Park West)

This American Elm stands across from the American Museum of Natural History, a 50.84-foot-tall arachnidian wonder, with a canopy spread of 55 feet. Uniquely, it’s wider than it is tall, with branches that graze the ground. To stand beneath it is to be both shielded and engulfed, like being taken under the wing of a benevolent dark angel. Its roots muscle under the surrounding cobblestones, heaving them up in surreal, undulating waves.

According to the New York Times, it is one of only 23 elms left on the west side of Central Park. Originally, there were 500, but Dutch elm diseases wiped them out. This elm is a neighborhood treasure, enjoyed by New Yorkers of all ages who marvel at its unique canopy. Its formidable roots remind us that even city sidewalks are no match when a tree stakes its claim.

6. Arthur Ross Pinetum (86th Street Entrance)

Like the Mall of Elms, this group of 600 pine trees is a single entry on the Great Tree list. It is the only entry for evergreens. In the original plan for Central Park, evergreens played a prominent role. Designers Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux planted a “Winter Drive”—a 30-block stretch of road visitors could enjoy from horse-drawn sleighs in the snow. But over time, the evergreens died and were replaced by deciduous trees.

Arthur Ross, a native New Yorker who made his name in the pulp and paper business, set out to return pines to the Park in 1971. Wanting to shield the view of the Great Lawn from the maintenance buildings on the 86th Street Transverse Road, he planted a grove of Himalayan pines. Those original trees are now 30 feet tall, and the Pinetum has expanded across the Park, adding about 35 trees a year. Home to seventeen species, from lands as distant as Macedonia, Japan and the Himalayas, it’s a most eclectic evergreen sanctuary—part tree museum, part miniature forest. Look for the distinctive leaning pines in the center section, and be sure to greet the small new saplings. Someday they will be as large as their neighbors.

7. Yoshino Cherries (East Reservoir)

1909 marked the 300th anniversary of Henry Hudson’s first encounter with the river that bears his name (known to the Lenape people as Mahicantuck). To commemorate the occasion, Japan sent a shipment of cherry trees, but the delivery was lost at sea. Three years later, the Japanese government made another arboreous gift to the United States—3,020 cherry trees were delivered to Washington D.C., now the site of the annual Cherry Blossom Festival. That same year, New York also received a delivery. Unlike DC, they opted to spread their cherry trees around the city.

For most of the year, the Yoshino cherry trees on the reservoir’s east side blend in unassumingly with the surrounding greenery, but in early spring, they turn a dreamy, fluffy white. They are the first cherry trees to bloom—usually in mid-April. You can find their vibrant pink cousins, the Kwanzan cherries, on the reservoir’s west side, and look here for where to find other cherry trees throughout the Park.

8. London Plane (Bridle Path near East 96th Street)

The London Planetree is New York’s most common species, comprising 12% of the city’s trees. A favorite of NYC Parks Commissioner Robert Moses, London Planes were planted throughout the city in the middle of the 20th century. But this one is special, as it has the distinction of being the oldest tree in Central Park. According to nature writer Dennis Burton, it may well have been planted when the Reservoir was dug in 1862, which dates it back to the Civil War.

You can’t miss it coming around the bend of the Bridle Path. It stands 95.94 feet tall with a diameter of over five feet, thanks to its distinctive multiple trunks. One limb juts out like a lightning bolt over joggers and passersby. If you get close enough, you can observe its bark, mottled and patchy like an impressionist painting. We recommend taking a moment, sitting beneath it, and feeling history against your back.

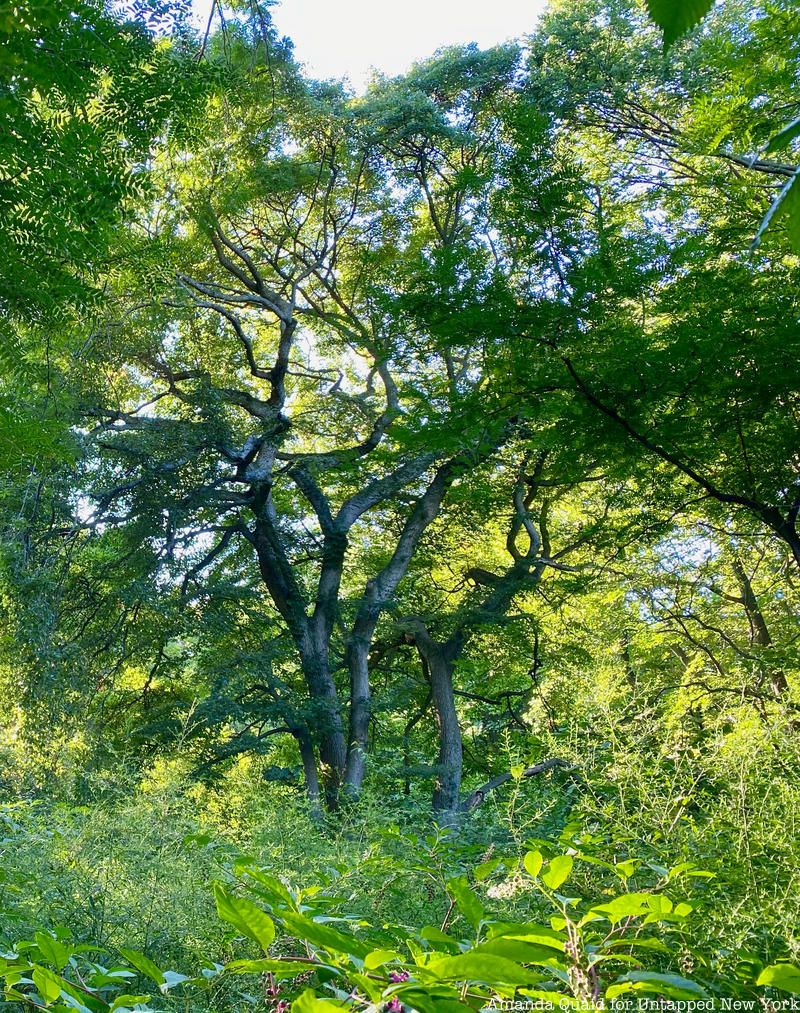

9. American Elm (East 97th Street Entrance)

This tree feels like an old witch, and being in its presence is a little unnerving. Every time we turned around, we thought it had moved one of the serpentine branches a little closer to us. Dating to the 1800s, this elm has survived Dutch elm disease, tree-felling superstorms, and much more. Its 80-foot canopy offers shade to weary walkers, as well as shelter to countless birds, mammals and insects. As the northernmost Great Tree of the Park, it stands tall in its 94.3-foot glory—a symbol of the strength and generosity of a true New Yorker.

10. Your Tree

Though most trees aren’t Great Trees, all trees are certainly great. They provide oxygen, absorb pollutants, and cool the air. They provide food, mark seasons, and their presence has even been shown to reduce violence. At the end of your tour of Central Park’s Great Trees, take some time and find another tree you’re drawn to. Perhaps you notice its height, the color of its leaves, or something distinctive about its bark. What makes it a Great Tree to you?

Next, check out The Best Places to See Cherry Blossoms in NYC and 10 Trees Not to Miss in Inwood Hill Park