Last Chance to Catch NYC's Holiday Notalgia Train

We met the voices of the NYC subway on our nostalgia ride this weekend!

To see an active quarry still in operation is rare. Yet at Stony Creek Quarry in Branford, Connecticut, an expanse opens deep and wide into the landscape, reflecting a rich history that is embedded in hundreds of buildings all over the United States. Stony Creek Quarry was a favorite of architects and architectural firms like McKim, Mead & White, Cass Gilbert, and Warren & Wetmore, who sought out its famous “Stony Creek pink” granite and placed it within what are now the nation’s most well-known landmarks, including Grand Central Terminal in New York City.

Just in New York City alone, Stony Creek Quarry granite appears as a major structural element in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Macy’s at Herald Square, Lord & Taylor on Fifth Avenue, Bellevue Hospital, 550 Madison Avenue, the George Washington Bridge, and many other buildings. But more than just a material of a bygone era, Stony Creek granite has been used on restorations of The Battery, Columbia University, and the Cooper-Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum in addition to new construction in the city. You can even find Stony Creek granite in public plazas and on sidewalks.

Its distinctive pink hue comes from the concentration of iron in the potassium feldspar of the granite, formed from the cooling and solidification of magma from volcanic disruptions. It is believed that the granite at Stony Creek was formed 600 million years ago when South America was originally attached to North America in the giant Pangea subcontinent. As per the book Flesh and Stone: Stony Creek and the Age of Granite, between 120 million and 200 million years ago, Africa split from North America, leaving behind the Stony Creek granite, and then between 60 million and 120 million years ago, South America split from west Africa creating the southern half of the Atlantic Ocean. A rift opened but did not fully cleave off the continent, leaving behind the Connecticut Valley.

While this area of Connecticut began as farmland, the salty, rocky terrain made it difficult to pursue even subsistence farming in ideal conditions. Fortunes changed with the development of the granite industry began in the mid-1800s. Quarries “were up and down the shoreline” of Connecticut, said sculptor Darrell Petit on our recent visit to Stony Creek. Petit has worked in all capacities with the Stony Creek Quarry for thirty years, first as a client and now as a de-facto spokesman and keeper of the quarry’s history. Of the twenty or so quarries that once operated on the Connecticut coast, only Stony Creek remains. “New York has always been our primary client, without a doubt,” Petit continued. He estimated that 75 to 85 percent of their business comes from New York City projects for “institutions that date back to the heyday” of the city.

The quarries provided a livelihood for newly arriving immigrants from Italy and Scandinavia, who brought their stone working skills with them. Proximity to the Long Island Sound offered easy access to waterborne transportation for the unwieldy goods, weighing in the dozens of tons. Railway expansion, along with a building boom during the Gilded Age led to an increased demand for granite.

The stately yet malleable material “proved to be … particularly suited to expressing both the aspirations of the well-to-do and the civic pride of growing cities. The desire to celebrate in stone the achievements of families, private institutions, and governments did not stop with the creation of mansions and imposing institutional edifices. It extended to memorials of past achievements, both in cemetery monuments and in prominently placed public art,” writes the contributors to Flesh and Stone: Stony Creek and the Age of Granite. Granite, a material that went well with the neoclassical architectural style popularized by the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, ended up in bridges, parks, buildings, monuments, and more.

Stony Creek Quarry supplied the granite for the base course of Grand Central Terminal. It is the stone that frames the storefronts along 42nd Street, all the way around the terminal, rising all the way up to the balustrades of the elevated roadway. Although the rest of the building is made of limestone, the granite is the most present material at street level to pedestrians. The quarry also currently supplies granite for the floors of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Even in Central Park, you will find Stony Creek granite on the bases of several sculptures like that of Romeo & Juliet, The Tempest, and the General Tecumseh Sherman Monument just outside the park.

A lot of Stone Creek Quarry’s work in New York City is connected to the restoration of landmark buildings in New York City or the construction of new buildings that need to have an architectural connection to an existing landmark. Petit explains how specific it can get: “Landmarks wants to know what exactly is authentic? And what is the treatment? This has been a big engagement with us in collaboration with really reputable and venerable institutions. Landmarks [are] unequivocal. If the quarry is alive, you need to get it from there. And that’s uncompromising,” Petit said.

“Part of my mission is to really be knowledgeable about what specifically Stony Creek did, rather than making these great general statements,” Petit explains. For example, the granite base of the Statue of Liberty is often attributed to this quarry but it actually came from the Beattie’s Quarry in Guilford, which sat right on the border of Stony Creek. Beattie’s also supplied the granite foundations for the Brooklyn Bridge. But since Beattie’s is closed, Stony Creek supplied the granite for the ramps of the new Statue of Liberty Museum. The commission came about because of “the desire to link in with the base” of the Statue of Liberty, Petit said.

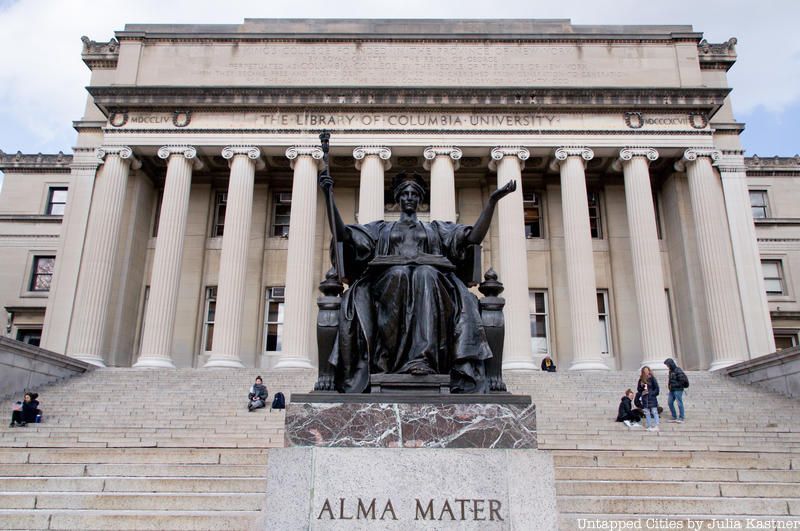

Stony Creek Quarry has also learned about the long-term benefits of working closely with its clients. In the construction of the new Northwest Building at Columbia University, the granite was going to be sourced from Portugal. Petit made a phone call to a professor he knew at Columbia who passed on the message that Stony Creek had supplied the granite for the original McKim, Mead & White campus. In fact, Petit said, the use of this particular quarry was an “ultimatum” by the original architects who used the quarry as a go-to source for projects like the Smithsonian Institute, Museum of History & Technology in Washington D.C., Columbia, and many more.

The university then instructed the architects to use Stony Creek, and now Columbia itself is one of the quarry’s primary clients. “I’ve seen how important it is to engage with the client and then the operators to stay involved. We are the material, but a big chain of events happens in between us, the farm, and the building,” Petit said. The quarry has since supplied the granite for numerous university hardscape projects over the last decade, including the restoration of the entrance to Butler Library, the plaza in front of the Mathematics Building, and the restoration of the steps and plaza leading to Low Library.

When working on projects, the quarry workers look for the part of the rock they refer to as a “solidity,” which can yield the large blocks that form the basis of the architecture world. These rectilinear units measure 10 x 6 x 4 feet, weigh 25 tons each, and “are recognized all over the world as a dimensional quarry block.” But Stony Creek Quarry has been operating for so long that it can do custom-size orders because it still has the know-how from the time prior to standardization.

One of those custom projects was the sidewalk in front of the Cooper-Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum on the Upper East Side. The large sidewalk pavers that border the museum are 12 feet by 7 feet, first sourced over a century ago from Stony Creek Quarry. With age, the granite got slippery and needed to be replaced. Petit contended that “you can go through New York City and see the world in the ground. And you see the world living in the ground for a hundred years. It’s not like buildings, which are on a 30-year development cycle. For me, it’s wonderful to participate in these great public projects that are for the people. And then it’s there for centuries.”

While the big slabs are now cut with top-of-the-line technology — a diamond impregnated wire, lubricated with wire and pulled to a tension that it can cleanly cut the granite — Stony Creek Quarry still uses all the methods historically available. That includes understanding the natural fractures in the rocks to identify where the rock will cleave easiest, using explosives, drills, sledgehammers, and more. “We’re still working with ancient technology as well as the most advanced,” Petit said.

Due to Stony Creek’s techniques, their yield is significantly higher than the industry average — 35 percent versus 5 to 10 percent elsewhere. The quarry has been good at making sure every possible piece of rock finds its best use. Odd-sized blocks will get turned into jetties, rip rap for shorelines, Belgian block, porous walking surfaces, and more for clients like the Army Corps of Engineers. The powdered silica that is a byproduct of the quarrying is being used by companies to re-mineralize farmland.

Another project Stony Creek Quarry has worked on was The Battery in Lower Manhattan. Work began on Battery Park with the construction of a perimeter sea wall that protects the park from future superstorms. The Battery was interested in echoing the granite of the Statue of Liberty. As a result, those in charge of Federal Plaza, just up the street, are looked to extend that material link too.

Another current is 550 Madison Avenue (originally the AT&T Building) which was built with Stony Creek granite by architect Philip Johnson. It was this building on Madison Avenue, with its “Chippendale” top that sparked a revival in stone as a building material starting in the late 1970s. Johnson, who had become synonymous with glass curtain wall design, decided that the heat loss was “too great.” That, coupled with the skyrocketing costs of aluminum, made him seek out other materials. Stony Creek Quarry supplied the granite floor for the restoration of 550 Madison by architecture firm Snøhetta, contractor AECOM Tishman, and developer Olayan in partnership with RXR and Chelsfield. The quarry is also involved in restoration work at Flushing Meadows-Corona Park.

Outside of New York City, Stony Creek granite can be found at Yale University, the Newberry Library in Chicago, South Station Headhouse in Boston, the Battle Monument at West Point, the Smithsonian Museum in Washington D.C., and a long list of more locations all around the country.

Like all quarries, Stony Creek Quarry has a limited life. It is the last of the nearly two dozen quarries that once operated in the area. By contract, the quarry also cannot excavate below sea level. As such, these are the last 55 acres, which are surrounded by land trusts from the communities of Guilford and Branford, that can be excavated. When the rock is gone, the quarry will close.

As we closed out our tour of Stony Creek quarry, we passed by a work-in-progress by Petit. His sculptures have been installed at Socrates Sculpture Park, Riverside Park, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the Peabody Museum of Art at Yale University, Chubu Museum and Cultural Center in Kurayoshi, Japan (a work in collaboration with Cesar Pelli and Associates), the Fort Wayne Museum of Art, and more.

Petit’s sculptures, often monumental in nature, respect the natural properties of the stones. He points out the “black flow” on the rock and how the movement of the sun affects the look. The rocks appear to be holding themselves up by sheer might, in a kind of stasis that might be disrupted at some point in the future — but not quite yet. Petit’s knowledge of the quarrying process has clearly directly influenced his artistic work. On our upcoming tour, you can learn more about Petit’s inspiration and how he creates these massive works of art. See more of his recent works in the gallery below!

Next, check out the missing granite eagles from Penn Station!

Subscribe to our newsletter