♀️ The Trailblazing Women of Wall Street

Women have long shaped Wall Street—even when history tried to write them out.

Jacob Wrey Mould is not one of the famous names that most people associate with the architecture of New York City or the design of Central Park, but the British-born architect was an important figure in both. After working on notable projects in England, he came to New York in the 1850s. In addition to designing residential homes and churches, Mould assisted Olmsted and Vaux in creating some of the most iconic structures in Central Park. He also had a hand in designing early iterations of New York City’s most important cultural landmarks. Mould served as Chief Architect for the New York City Parks Department and was a master of the Victorian Gothic style. He is buried in Green-Wood Cemetery. Though many of Mould’s distinctive buildings have been lost, we can see his unique style in the wonderful structures that remain. Read on to discover all of the Mould designed works in New York City!

City Hall Park is one of the oldest parks in New York City and contains perhaps the most well-known piece of Mould’s work, the City Hall Park Fountain. The first fountain to grace the park was put in place in 1842 to celebrate the Croton Aqueduct’s completion. The aqueduct brought clean, safe water from upstate New York to the city. A few decades later, Jacob Wrey Mould was commissioned to design a new fountain for the park’s south end. Mould’s extravagant Victorian design features a thirty-foot square granite basin with a granite and bronze central column rising from the middle. Four elaborate, gas-lit candelabra adorn each corner, and every side has a small semi-circular pool.

Mould’s ornate design was celebrated at the time, but after World War I, taste changed. New Yorkers no longer valued the fanciful fluff of Mould’s Victorian fountain. In 1920 it was shipped up to Crotona Park in the Bronx. New Yorkers disliked the new fountain, an allegorical depiction of “Civic Virtue,” even more than Mould’s design, so it was shipped to Queens. The park remained fountainless until 1972 when philanthropist George T. Delacorte gifted a new one. In 1995, Mayor Rudolph Guiliani sought to spruce up City Hall and its adjoining park with a $35 million renovation. Part of that project included the extensive restoration and reinstallation of Mould’s fountain. The fountain had been stripped of many ornamental features and covered in graffiti. Still, the conservation firm in charge of the restoration replaced all missing granite, bronze, and ceramic elements using Mould’s original sketches and photographs.

Before Tavern on the Green was a restaurant, it was a sheepfold. Like many of our favorite Central Park sites today, the Victorian Gothic structure designed by Calvert Vaux and Jacob Wrey Mould wasn’t in the original plans for Central Park. It was eventually built in 1870. The polychromatic masonry on the facade, made of red brick with contrasting bands of white and gray gneiss, is a signature element of Mould’s work, and you can see this feature in many of his buildings. The most extreme use of this technique was in Mould’s design of the All Souls Unitarian Church on Park Avenue South. The 1855 church no longer exists, but it gained the nickname “Holy Zebra” because of its multi-colored stripes.

During the day, hundreds of sheep grazed on the fifteen acres of lawn at Sheep Meadow on Central Park’s west side. They slept in the sheepfold at night. In 1934, Parks Commissioner Robert Moses had the sheep relocated to Prospect Park in Brooklyn and converted their nighttime home to a restaurant. While the establishment has seen many renovations, additions, and different owners over the decades, it has always been called Tavern on the Green.

The impressive Beaux-Arts facade of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, designed by Richard Morris Hunt, is the image that comes to mind when we think of the museum today. However, the building had much humbler beginnings. Land between 79th and 84th Streets in Central Park was designated for the Metropolitan Museum of Art by the City of New York’s Department of Public Parks on March 20, 1872. Though Olmsted and Vaux wanted only recreational structures in the Park, Central Park’s treasurer, Andrew Haswell Green, successfully pushed for an art gallery. Before the museum came to Central Park, it was housed in a simple brownstone at 681 Fifth Avenue and then in a mansion at 128 W. 14th Street.

Vaux and Mould’s Central Park museum building was completed in 1879. Employing the Gothic Revival style, the brick facade featured pointed arches above the windows and vertical lines to evoke a sense of height. Ornamental tiles and carved reliefs planned for the facade were never installed. The designers already knew that their external walls would eventually be covered by additional wings added to the museum over time. You can still see Vaux and Mould’s original Victorian Gothic façade in the Robert Lehman Wing (Gallery 961/962). That section of the facade would have looked onto Central Park. In the second-floor passage that leads from the Grand Stair south towards the Impressionist wing (Gallery 690), you can see a piece that would have been part of the eastern facade facing 5th Avenue.

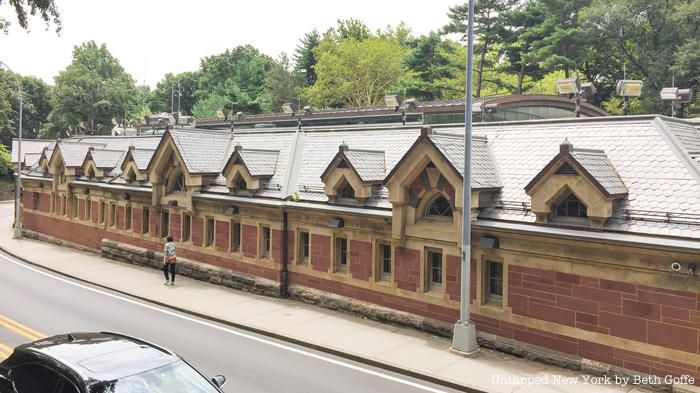

The 22nd Precinct of the NYPD, the oldest precinct in the city, operates out of horse stables designed by Mould and constructed in 1871. Located at the 86th Street transverse in Central Park, the low brick and brownstone structure once housed up to thirty horses used for work around the park. The stables were connected to two other buildings, an open shed and a small supervisor’s cottage. The shed backed up against the former Central Park reservoir, which you can still see remnants of inside the station. Calvert Vaux is widely and mistakenly credited with the building’s design.

In 1936, Robert Moses had the cottage torn down, and he moved the Central Park police from the Arsenal into the stable house. Over the years, the building was not well cared for. There was some restoration work done in the 1990s, but in 2001 the police moved out. The force moved back into the stable house in 2011 after a $61.7 million renovation project, which included installing a partially bullet-proof glass atrium, central air-conditioning, 2,300-square feet of additional space, and more upgrades.

Bethesda Terrace and its fountain are perhaps the most recognizable icons of Central Park, and Mould helped design each of them. The terrace was one of the first structures built in the park. Considered Vaux’s masterpiece, work began on the terrace in 1859. Vaux wanted the carvings which adorn the terrace to have a wildlife and seasonal motif. Mould brought Vaux’s concepts a reality through his relief carving designs. Walking around the terrace, you see beautifully intricate carvings of vines and leaves weaving around birds in flight, niches filled with tiny sculptures of woodland creatures, and ornamental designs made of flowers and fruit.

Inside the terrace gallery, Mould designed the colorful patterns found on the tilework. The Minton Tile company in England created the tiles based on Mould’s designs. There are more than 15,000 of them! It is the only place in the world where you will see Minton tiles, a popular floor tile in the 19th-century, on the ceiling.

Bethesda Fountain, formally titled Angel of the Waters, was the only sculpture commissioned during the original design of Central Park. Sculptor Emma Stebbins created the twenty-six feet high fountain. Stebbins was the first woman to receive a commission for a major public work in New York City. Vaux designed the base it stands on, and Mould created the ornamentation, including four cherubs representing Temperance, Purity, Health, and Peace.

While New York City still boasts many remnants and ornamental structures designed by Mould, the only extant building we have of his is the Parish House at the Serbian Orthodox Cathedral of St. Sava (formerly Trinity Chapel). Built in 1860, the Victorian Gothic building originally served as the Trinity Chapel School. All of Mould’s signature design elements can be found in this building, from the pointed arch windows and polychromatic masonry to decorative tile work. New York is especially lucky to have this building after a devasting fire in 2016, which nearly claimed the Cathedral.

You can see striking similarities to the original Metropolitan Museum of Art facade in the original American Museum of Natural History designed by Jacob Wrey Mould and Calvert Vaux. When commissioned for the project in 1872, Vaux and Mould came up with a grand plan that would take up the entire Manhattan Square site. Their ambitious design included an enormous five-story square with a Greek cross in the middle that would create four enclosed courts with a central octagonal crossing, covered with a dome. Initial funds for the museum were modest, so they started small. The cornerstone of the first building at 77th Street was laid by U.S. President Ulysses S. Grant, and it opened three years later. President Rutherford B. Hayes presided over the opening ceremony.

You can still see part of Vaux and Mould’s original facade on Columbus Ave. However, it is blocked by the construction of the new Richard Gilder Center for Science, Education, and Innovation designed by Studio Gang. It is unclear if the facade will be covered by the new wing or left exposed.

Belvedere Castle in Central Park was recently renovated, and in the process, an original detail designed by Jacob Wrey Mould was restored. Original plans for the castle called for an additional stone tower in the northwest corner, but it was never built. Instead, Mould designed a decorative wooden loggia and tower to fill the space. Due to structural issues, the tower was torn down in 1872 and remained lost until it was restored in 2019. The wooden tower is a tribute to the original architects’ vision of the castle as a “picturesque” structure. It now adds balance to the architecture as you gaze up at Belvedere from below.

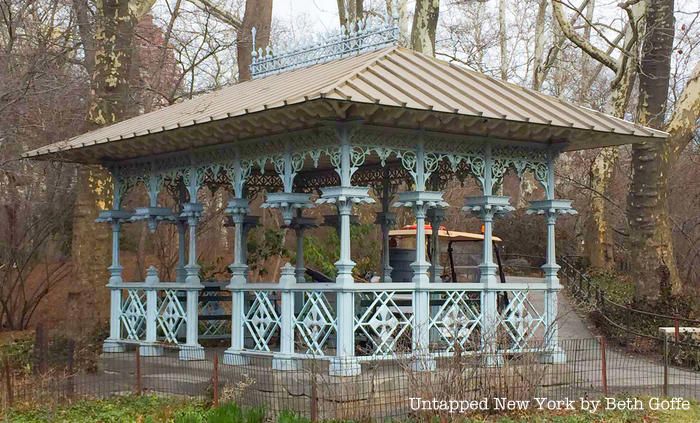

Now a perfect spot to catch some shade and take in views of the Manhattan skyline and the Lake, the Ladies Pavilion by Jacob Wrey Mould originally served as a trolley stop. Built in 1871, the bright blue cast-iron structure was placed near the entrance at Central Park West and 59th Street. It was moved in 1912 to a secluded position near the former Ladies Pond site, a skating spot where women could skate privately. The picturesque pavilion is now a much sought after spot for weddings and special events throughout the year.

The beautiful Cherry Hill Fountain at 72nd Street on Central Park’s west side wasn’t always just something pretty to look at. After it was built in 1870, the fountain served a practical purpose. It was a rest stop and turnaround for horseback riders and horse-drawn carriages. Horses could drink from the fountain while their riders found respite in the stunning views of the Lake. In true Mould fashion, the fountain is designed with elaborate ornamentation. Patterned Minton tiles ring the central column, bronze and wrought iron details add delicate flourishes, and polished granite gives it a strong, stately stance.

Jacob Wrey Mould assisted Calvert Vaux in designing many of Central Park’s dozens of bridges and archways. Perhaps the most recognizable is Bow Bridge at 74th Street. The storybook bridge’s walkway is sixty-feet wide and made of planks of ipe, a South American hardwood that turns a deep red when wet. The ever-changing colors of the foliage in the Ramble woodlands, the whimsical design of the bridge, and the reflective waters of the Lake make Bow Bridge one of Central Park’s most popular destinations.

A few arches Mould helped design include Willowdell arch, Dipway arch, Greengap arch, and Playmates arch, among others. Mould was also responsible for the original design of the Gapstow Bridge, which he modeled after railroad bridges. The wood and cast-iron features of Mould’s bridge didn’t weather well, and in 1896 it was replaced by a simple stone bridge designed by the firm of Howard & Caudwell.

Next, check out 10 Historic Ruins and Remnants Inside NYC’s Central Park and Blockhouse of Central Park: A Military Ruin Predating the Park

Subscribe to our newsletter