This election year has been especially fraught and you may find yourself reaching for a drink to help calm your election day anxiety. When you raise a glass today, you will be carrying on a tradition of election day drinking that dates back centuries. From revelrous colonial parades to 19th-century polling stations in saloons, alcohol has played an important role in American democracy.

In colonial New York, elections were accompanied by great fanfare. Candidates often arranged transportation for voters to get from their rural homes to the voting site in town. Election day was a day of celebration and the march of voters often turned into a rowdy parade fueled by food, booze, and political fervor. There were even special foods made for the occasion including Election cake, a boozy and buttery fruit-like confection found in America’s first known cookbook, Amelia Simmons’s American Cookery from 1796. Once at the polling site, a tavern or the house of a gracious host nearby would serve as a place for voters to continue eating food and drinking libations provided by the candidates, while the candidates tried until the very last minute to their votes.

Not even the great George Washington was against offering booze for ballots. In his book Last Call: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition author Daniel Okrent writes that after losing a bid for a seat in the Virginia House of Burgesses, Washington credited the loss to not providing enough alcohol for the voters. The next time around, Washington “floated into office partly on the 144 gallons of rum, punch, hard cider and beer his election agent handed out—roughly half a gallon for every vote he received.”

Image via Library of Congress

Image via Library of Congress

Once at the voting green, crowds separated into groups based on which candidate they supported. The candidate with the larger supporting crowd won. Sometimes, an actual poll was taken, but not with written ballots, with oral votes instead. Secret ballots were considered “unmanly” at the time and would not be introduced in America until the 1880s. No matter what the outcome of the election, everyone was expected to adjourn to a local tavern for more drinks and celebratory feasting, at the winning candidate’s expense.

Alcohol and revelry continued to be part of American elections after the revolution and into the 20th-century. In the late 1800’s, the saloon, like the tavern before it, became a center for politics. Saloons provided men, largely lower class and immigrant workers, with a communal space where they could air their political grievances. Political parties would often set up headquarters inside saloons to hear what issues the patrons were talking about.

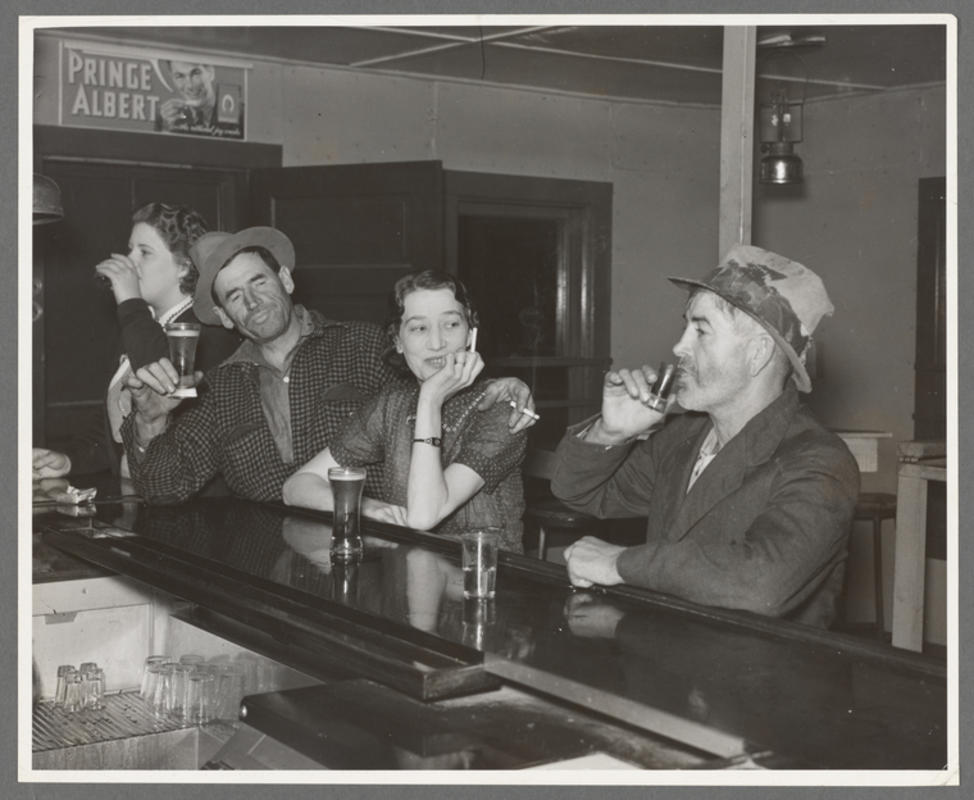

McSorley’s Old Ale House in NYC, Image via New York Public Library

McSorley’s Old Ale House in NYC, Image via New York Public Library

The saloon, often the biggest building in a community, often served as a meeting place for various social organizations. Not only could you talk about politics in a saloon, but you could also cast your vote there. In New York, nine out of ten polling places in immigrant neighborhoods were in saloons. Fire stations, warehouses, and even livery stables were other popular polling venues in 19th-century cities.

In The Vote, a PBS documentary about women’s suffrage, historian Ellen Dubois explains how voting was very comfortable for men, not so much for women. “The polls are in tobacco shops, they’re in saloons. They are in places where men are very comfortable, where they carouse, where their political bosses can lubricate them with a drink here and there.” Much like it was back in colonial times, writer Michael Waldman says voting in the 19th and early 20th-centuries “was a big party, it was raucous, it was drunk, it was often violent. Turn out among men was very high. It was like a festival and a spectator sport all at once and well-bred women showing up in that environment would not have been a very welcome sight.”

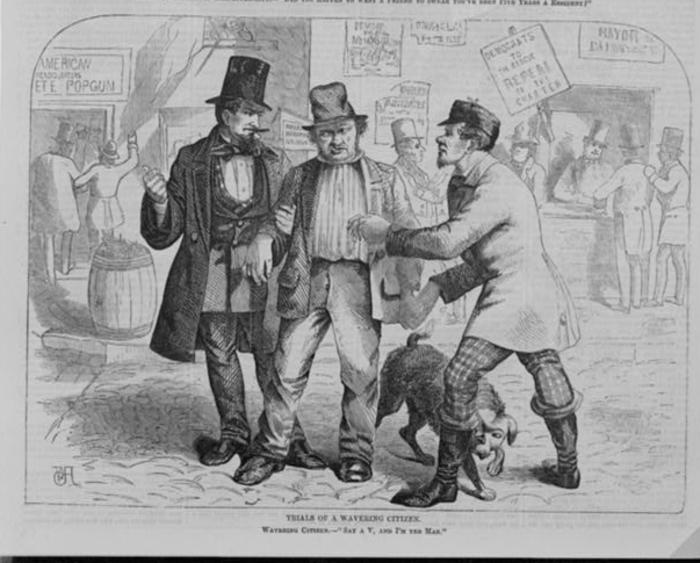

While the drinking and revelry that surrounded colonial elections were fairly jovial, by the 19th and early 20th centuries, concerned citizens started to be wary of mixing alcohol and voting. For one, it seemed to exacerbate the problems of voter fraud, voter intimidation, and bribery. Saloonkeepers and their associated gangs often had a particular political agenda to enforce. The muscle would make sure patrons were registered to vote and that come election day, they voted for “the right” candidate. Gangs would also practice what was called “cooping,” where they would kidnap an unsuspecting man, give him drugs or alcohol, and drag him to multiple polling places, dressed in different clothes, to cast fraudulent ballots. Cooping has famously been posed as one theory to explain the mysterious circumstances under which Edgar Allan Poe was found incoherent outside a polling place in Baltimore before his death.

Politicians Trying to Buy Votes, Harper’s Weekly, Image via Library of Congress

Politicians Trying to Buy Votes, Harper’s Weekly, Image via Library of Congress

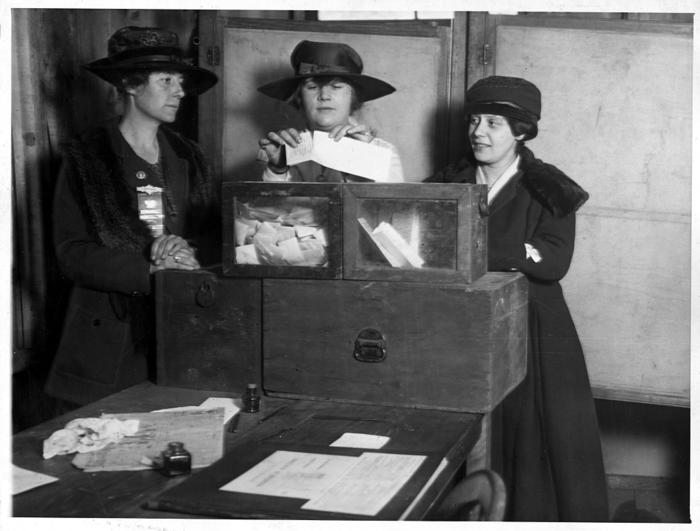

Election Day drinking was hampered by the temperance movement, which waged war on the saloon, and eventually the passage of prohibition in the 1920s. The prevailing thought of the temperance movement was that by ridding communities of saloons, other social evils would be eliminated too. Closing down the saloons would also mean taking election proceedings out of the domain of men. Temperance was closely associated with women’s suffrage. Some see the war against saloons however not as a righteous cause, but as an act of suppression by the upper classes who were worried about the political influence held by the large, rapidly growing, and politically engaged working classes.

Some women were perfectly fine with leaving voting to the men. Mrs. William A. Putnam, an important socialite and wife of a millionaire banker, hosted many events, clubs, and parties in her home at 70 Willow Street (Truman Capote‘s home) in Brooklyn. The most notable of Mrs. Putnam’s events were meetings of her anti-suffragist group which began in 1894. The ladies of this group felt that voting would be a “burdensome duty,” and that it would deprive women of “special privileges. Mrs. Putnam continued advocating against the right for women to vote for more than twenty years.

Image via Library of Congress

Image via Library of Congress

Today, you will most likely cast your vote in a school or church. Public buildings that are ADA compliant are ideal polling stations, but the specific requirements still vary by state. Some states, like Montana, don’t specify any requirements at all, while others, including New York, state that polling stations can not be within a certain proximity to alcohol-serving establishments. Until 2014, when South Carolina passed new legislature, the sale of alcohol was still banned on Election Day in some states. The laws often dated back to the 19th-century and were a holdover from the backlash to saloons. Thankfully, there are no more restrictions on obtaining alcohol today, so after you cast your ballot, you can buy yourself a drink. Cheers!

Next, check out Voter Guide for New York 2020 Election