It’s hard to imagine walking through New York City without passing by a store that sells bagels. But did you know that in 1951, the city witnessed its first “bagel famine”? When members of bagel union Local 338 went on strike, 32 out of 34 bakeries closed down, and sales for lox plunged from 30 to 50 percent. The usual 1,200,000 bagels usually in demand during the weekends was not met, depriving those The New York Times called “addicts of the roll with a hole.” To their disappointment, only egg-bagels and bialys were available for sale at delicatessens. Even a theater performance, called “Bagels and Yox” could not distribute its complimentary bagel with cream cheese to audiences. The theater had to distribute doughnuts instead. After seven weeks of striking, union members and bakeries finally reached an agreement, bringing an end to the first “bagel famine.”

An advertisement for the show Bagels and Yox. Image from New York Public Library.

Bagels were not always a staple in the American diet. They were first brought to New York City by Jewish immigrants who had enjoyed eating and baking bagels for several centuries in Eastern Europe. By 1900, there were seventy bagel bakeries in the Lower East Side.

Kossar’s Bagels has been around since 1936

Kossar’s Bagels has been around since 1936

In the basements of those bakeries, you would find bakers drenched in sweat and soot as they poured hours of painstaking labor into prepping, mixing, and baking the dough. Bakers were confined to 120-degree, insect-infested-basements for 13 to 20 hours a day. In those cramped, sweltering conditions they toiled and slept for seven days a week.

These poor conditions led bakers to form Local 338, a union under the Bakery and Confectionery Workers International. Founded in the 1930s, the union was made up of approximately 300 members. The art of the bagel was exclusive to Jewish immigrants and their sons who learned the craft from their fathers. But simply having family connections was not enough to join Local 338. To qualify, newcomers had to be able to roll the bread at a rate of 832 bagels per hour.

Local 338 was more than a union: it was a tight knight community whose members shared the same Jewish culture, Yiddish language, and expertise of bagel-making. As a result, they wielded the ability to bring a screeching halt to bagel production in New York City at any time and for as long as they wished.

According to Maria Balinska’s book The Bagel: The Surprising History of a Modest Bread, the contracts of bagel bakers were open for renegotiation at the beginning of every year. If bakeries failed to meet the demands of Local 338, the union would often go on strike. Strikes generally fought for higher wages, shorter hours, better working conditions, and longer paid vacations. Soon enough, bagel bakers went from making as low as $3 a week to as much as over $250 a week.

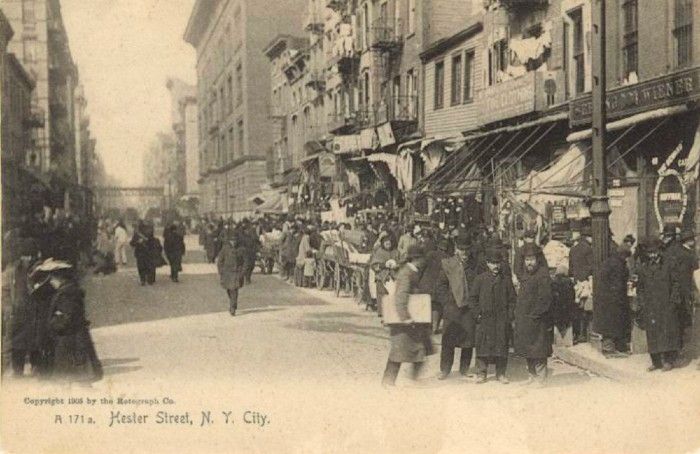

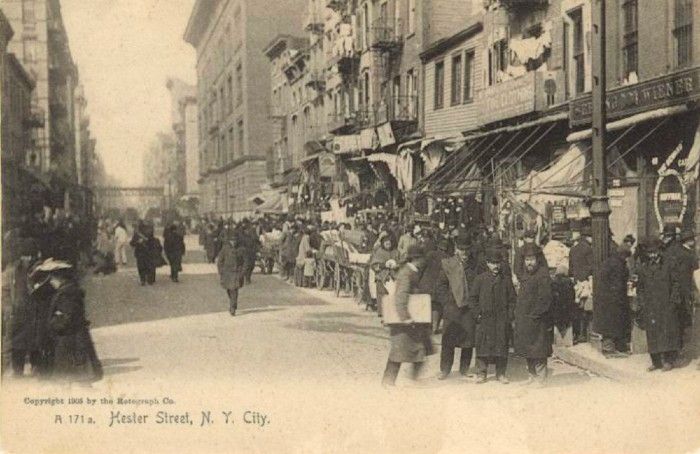

The first bagels were baked in bakeries along Hester and Rivington Streets in the Lower East Side. Image from New York Public Library.

The 1951 bagel famine may have been one of the union’s most impactful, but it was certainly not the last. In 1957 union members went on strike again, only this time, when bagel truck drivers refused to join, bakers sabotaged trucks and stole car keys until the drivers eventually joined.

The second and most successful strike for Local 338 was in 1962. The 1962 strike was notably different because Local 338 was not alone — six unions joined, with a total of around ten thousand bakers refusing to work for nearly a month. Weekly production of bagels was cut down by almost 85% until both bakers and bakeries finally came to an agreement.

However, the 1962 strike would be the last influential strike the union would witness. With the advent of Daniel Thompson’s bagel machine in 1963, Local 338 lost its influence over bakeries. Thompson’s machine, which could produce about double the amount of bagels two bakers could create by hand, soon replaced Jewish bakers.

With freezers, preservatives, and other technology that dramatically simplified the production of bagels, the bagel soon became the bagel we know of today: mass-produced, available in a variety of colors and flavors, and a staple in American breakfasts, lunch, and for some, maybe even dinner.

The popularity of the bagel also led to the disintegration of Local 338. Bakers eventually left the union as its influence waned and job prospects as bakers faded as well. There were only 152 members by 1971, and after a new bagel union formed, Local 338 disbanded.

Rainbow bagels from Brooklyn’s The Bagel Store

But let’s not forget the great bagel strike of 1997, when Kramer on Seinfeld gets notified that H&H Bagels has finally ended its twelve year strike. Then, Kramer goes on strike again to request a day off to celebrate Festivus and pickets in front of the shop with the sign “FESTIVUS YES! BAGELS NO!”

Today, we can happily shop for and enjoy our bagels without the fear of an impending bagel famine. But perhaps when we reach for the plastic-wrapped and mass-produced rolls, maybe we should mourn the bagels of the first bagel bakers. Their hand craftsmanship may no longer be available in every bagel we find, but we can still take every bite of those glossy, doughnut-shaped rolls in memory of their grit and hard work.

Next, check out the history of the NYC bagel, best Knish bakery in the Lower East Side and Photos: World’s Largest Salmon Lox Bagel