Marcus Garvey Park in Harlem, renamed in 1913 after the Jamaican and Black pan-nationalist, immortalizes Garvey into the public space of New York City. This area, known as Snake Hill during the Dutch colony, has been preserved as public space since 1840 when it was called Mount Morris Park. Garvey’s time in New York, from 1916 to the early 1920s, is worth revisiting as it is relevant to contemporary racial issues, but Garvey remains relevant also in the urban geography and history of New York.

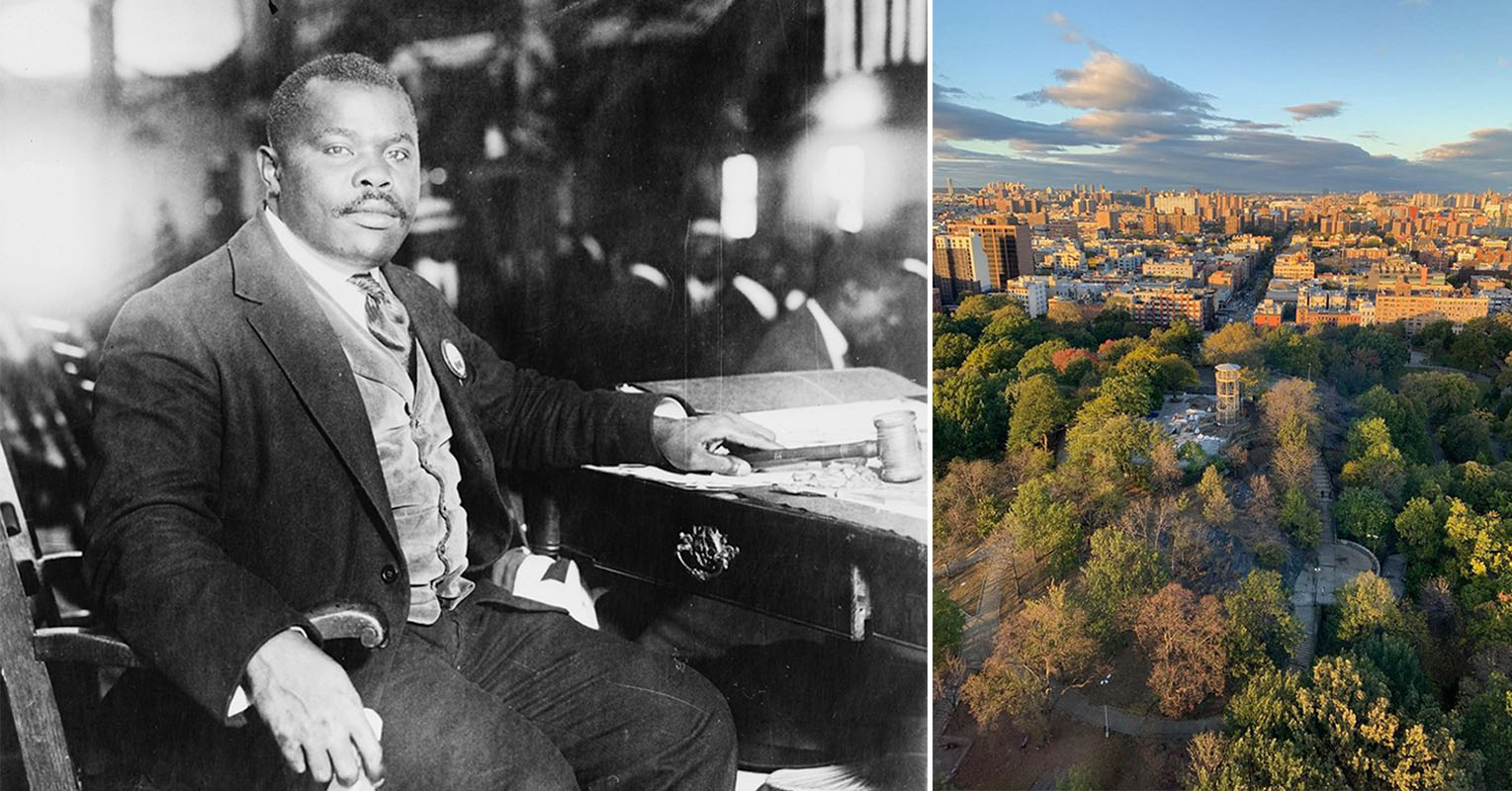

An aerial view of Marcus Garvey Park, courtesy of AFineLyne

An aerial view of Marcus Garvey Park, courtesy of AFineLyne

To read about Garvey and the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) is an invitation to learn more about New York, Harlem, and, above all, the history of race in the United States. In retrospect, Garvey and New York fit so well together, almost as an inevitable crossing of paths. On one side Garvey, as a prolific traveler from the Anglo-Caribbean diaspora, and on the other, New York as a migratory hub for Caribbean Blacks and the center of an emerging African American intelligentsia.

World War I and the Racial Backlash

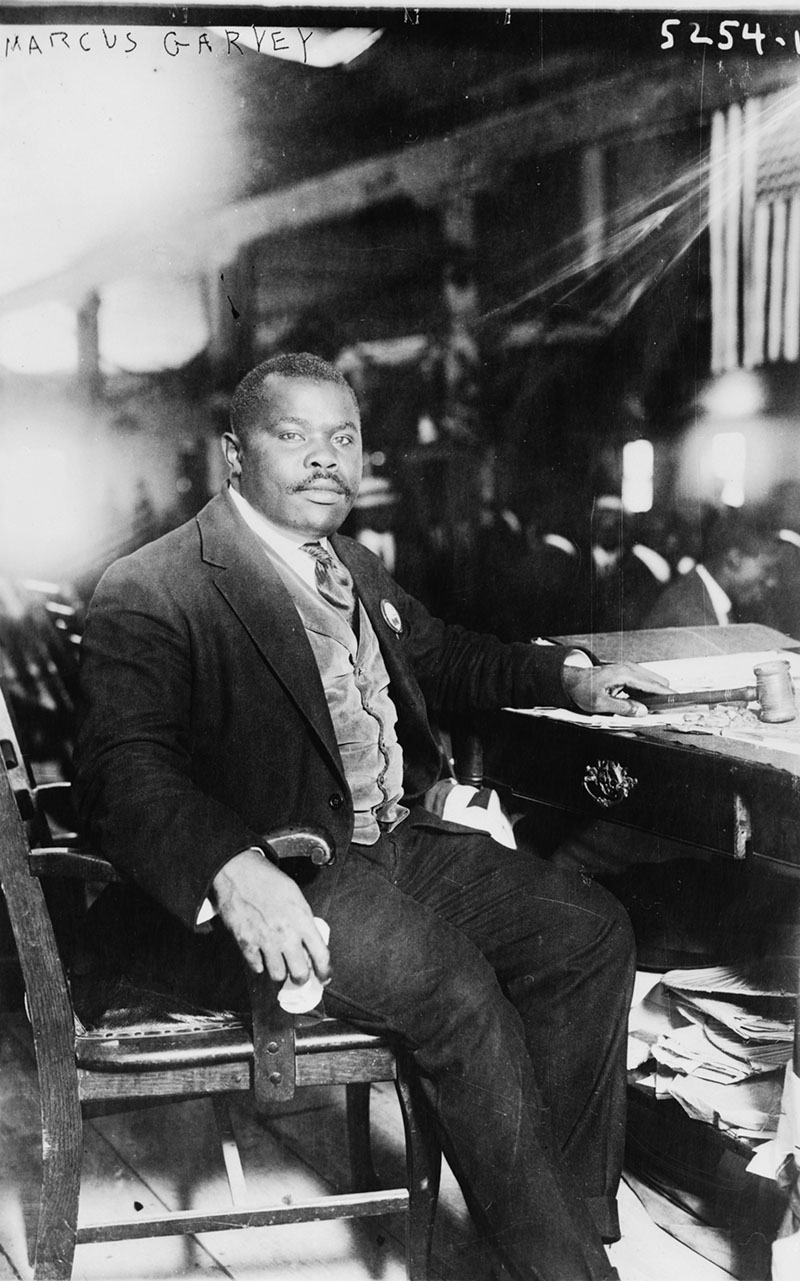

Portrait of Marcus Garvey in 1924. Photo from Library of Congress.

Portrait of Marcus Garvey in 1924. Photo from Library of Congress.

The mid and late 1910s was an unraveling time as World War I was underway, bringing to the forefront ideas such as self-determination of ethnic and racial minorities, a new wave of nationalism, and the first calls for decolonization. Marcus Garvey represents that moment when imperial subjects across borders became aware of each other’s common oppression and destiny through the globalizing world of war mobilization and trade and labor migration. Garvey likely borrowed ideas from the many other nationalist and liberation struggles in England during this period, including perhaps Irish and Egyptian nationalist movements and Zionism.

The period following World War I was significant for race relations in the United States. For African American servicemen returning from Europe, the immediate interwar period was characterized by a white racial backlash, aimed at restoring pre-war racial social hierarchies. For example, white planters expected Black veterans to return to low paid farm work, while other whites feared that stories about African American soldiers’ liaisons with white women in France would threaten racial boundaries in the American South. The lynching of Black veterans, even when wearing their uniforms, became common news in the South. Victims such as Leroy Johnston from Arkansas, murdered during the Elaine Massacre, or L.B Reed from Mississippi come to mind; the latter one murdered for having a relationship with a white woman. This violent period in American history started with 1919’s “Red Summer” and culminated with the Tulsa race massacre of 1921.

Garvey in New York

Marcus Garvey’s first apartment at 53 West 140th Street

Marcus Garvey’s first apartment at 53 West 140th Street

Marcus Garvey arrived in New York in March 1916, during the prelude to “Red Summer.” Garvey’s initial motivation for visiting New York was to discuss with Booker T. Washington the establishment in Jamaica of Tuskegee style industrial and agricultural schools. The first address Garvey provided as his residence in New York was 53 West 140th Street.

Bethel AME Church where Garvey gave a speech that put him on the map

Bethel AME Church where Garvey gave a speech that put him on the map

Soon after his arrival in New York, Garvey went on a speaking tour of the United States, visiting thirty-eight states. On June 12, 1917, after an invitation from writer Hubert Harrison, Garvey gave a speech at Bethel AME Church in Harlem which propelled his popularity in New York. Soon thereafter, Garvey hosted weekly meetings at Lafayette Hall at 131st Street and Lenox Avenue.

In 1917 Garvey founded the New York branch of UNIA (Universal Negro Improvement Association), located at 235 West 131st Street. UNIA eventually grew from its founding in Jamaica in 1914 to 725 branches in the United States and hundreds of branches around the world. The ideology of UNIA, as the acronym makes obvious, sought social and economic empowerment for Blacks through economic self-reliance and racial pride. Other more controversial principles of UNIA included racial separatism, racial purity, and the back to Africa Movement.

The former Universal Negro Improvement Association New York headquarters at 235 West 131st Street

The former Universal Negro Improvement Association New York headquarters at 235 West 131st Street

As a man of his time, Garvey, arguably, was fighting Western imperialism and white supremacy by appropriating their language and ideas against them. An example of this approach was embracing religion while replacing the image of God as a white man with a Black man. Another example of Garvey’s adoption of Western idioms or tropes was his promotion of red and blue uniforms and marches that seemed to evoke some type of royalism or Anglophilia. Even in his own attire, Garvey displayed an imperial or Napoleonesque persona, decorated with a chapeau with plumes and a blue military cloak. In addition, as someone well aware of the symbolic and performative aspects of any nationalist movement, for Garvey flags and marches in Harlem, along Seventh and Lenox Avenues, represented a form of propaganda as well as a test of the popularity of his controversial movement, which attracted admirers, detractors, and curious passersby.

Garvey and Black Self-Empowerment

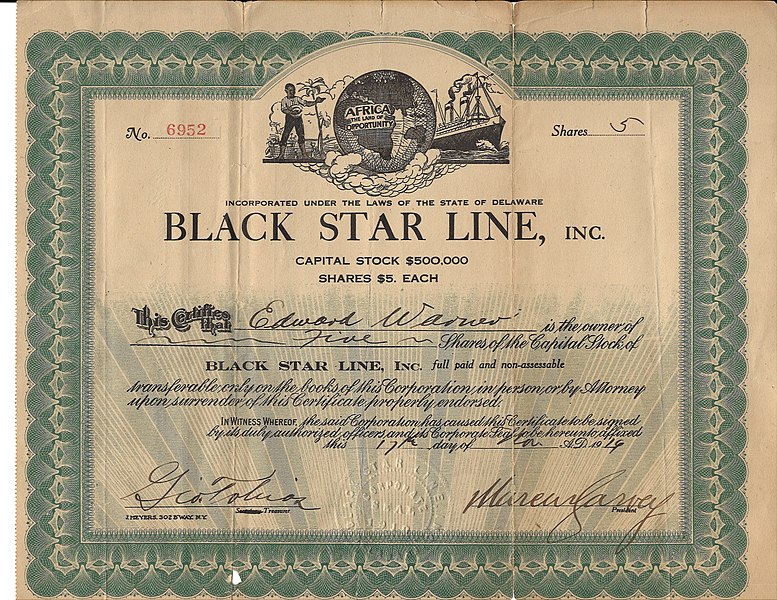

Black Star Line Shipping stock certificate signed by Marcus Garvey. Image from Wikimedia Commons.

Black Star Line Shipping stock certificate signed by Marcus Garvey. Image from Wikimedia Commons.

The end of World War I brought an atmosphere of disillusionment to African Americans and other Blacks living under racist regimes. The Peace Conference of 1919 in Paris ignored the calls for self-determination from colonized peoples in the French and British empires. UNIA had called for the transfer of former German colonies to Africans, but the establishment of the Mandate System by the League of Nations proved that European powers were not interested in ceding control. This setback did not dissuade Garvey from his principle of self-reliance. Garvey believed Africa should be for Africans, which in practical terms meant leaving the development of Africa to an elite of Africans. To achieve this end, Garvey founded the Black Star Shipping line that would connect Africa commercially to the world.

Marcus Garvey speaking at Liberty Hall in 1920. Photo in public domain from Wikimedia Commons.

Marcus Garvey speaking at Liberty Hall in 1920. Photo in public domain from Wikimedia Commons.

In August of 1920, UNIA held the First International Convention of the Negro People at Madison Square Garden with delegates from 22 countries and over twenty-five thousand people in attendance. Other sections of this convention met at Liberty Hall on W 138th Street in Harlem, a venue Garvey had acquired in 1919. Later in 1922, the historical Black Abyssinian Baptist Church was constructed next to Liberty Hall. The convention enacted the Declaration of Rights of the Negro Peoples of the World. Some of the demands from this convention, which still sound relevant a century later, included the teaching of black history in school, equal wages, equality before the law, and the end of lynching. The 1920 Convention also adopted red, black, and green as the colors of the Pan-African flag.

The Abyssinian Baptist Church, next to the former Liberty Hall

The Abyssinian Baptist Church, next to the former Liberty Hall

Perhaps today Garvey’s insistence on economic self-reliance is an over-simplistic solution to complex historical and systemic injustices. However, Garvey’s cooperative Black capitalism produced, nonetheless, some tangible results throughout New York City. UNIA opened a collection of Black businesses which included grocery stores on 47 West 135th Street, 646 Lenox Avenue, and 552 Lenox Avenue; restaurants at Liberty Hall at 114 W. 138th St. in Harlem, and 75 West at 138th Street; a printing plant on 2305 Seventh Avenue, and an industry center on 62 West 142nd Street.

Apartments built atop the site of the former Liberty Hall at 114 West 138th Street

Apartments built atop the site of the former Liberty Hall at 114 West 138th Street

While Garvey’s message of Black empowerment and liberation was a threat to British and French colonialism, the United States government considered Garvey as a racial agitator. A young J. Edgar Hoover, working for the General Intelligence Division, prosecuted Garvey for mail fraud in 1922. In 1927, US immigration deported Garvey back to Jamaica. He continued his efforts for the UNIA there, and later in London where he died in 1940.

A memorial procession took place in Harlem after his death, and Colin Grant writes in the book Negro with a Hat: The Rise and Fall of Marcus Garvey that “perhaps the most elaborate ceremony took place in Harlem where members planned a processions through the streets to the memorial service, carrying a huge photograph of Garvey, escorted by uniformed members of the African Legion, and followed by congregations and choirs.”

There are no statues to Marcus Garvey in New York City, but two more places were named in his honor, both in Brooklyn. Marcus Garvey Boulevard in Bedford-Stuyvesant and Marcus Garvey Village, an affordable apartment complex, in Brownsville. Completed in 1976, Marcus Garvey Village was part of a movement by Governor Nelson Rockefeller to elevate the design of affordable housing, recruiting the top starchitects of the time. Marcus Garvey Village was designed by Kenneth Frampton, in partnership between Rockefeller’s Urban Development Corporation and an architectural research firm led by architect Peter Eisenman. The New York Times described Marcus Garvey Village as something that “resembled student co-ops on progressive college campuses. Apartment doors opened to the outside rather than onto hallways; the units had communal mews and private backyards.” The internal courtyards inadvertently shielded criminal activity from view, according to the Times, and “ultimately, the distinguishing elements delivered consequences radically different from the grand intentions.”

Next, discover the restored Harlem Fire Watchtower in Marcus Garvey Park and read about why Giuseppi Garibaldi has a statue in New York City.