Art Deco architecture is at the core of New York’s identity and Ralph Walker was a key figure in creating this signature style. He designed buildings that are widely admired and today his name is a by-word for beauty and quality. Untapped New York has featured Walker’s work before, but now we are taking a deeper dive into the architect and his works.

AT&T Long Distance Building

A native New Englander who was born in 1889 and studied architecture at MIT, Walker worked in Providence, Montreal, and Boston before arriving in New York around 1916. After World War I military service in France, in 1919 he began working at McKenzie, Voorhees, and Gmelin, a firm known for its work for the New York Telephone Company, which was part of the Bell System monopoly.

Barclay-Vesey Building Lobby

Barclay-Vesey Building Lobby

In 1921 opportunity called for Mr. Walker. New York Telephone needed a new headquarters and Walker served as the chief designer. It would be located on the full block site located at 140 West Street in Lower Manhattan and was named for the streets bounding it on the north and south — Barclay-Vesey.

NY Telephone Long Island Headquarters, Brooklyn

Walker established a new prototype with the Barclay-Vesey Building which he subsequently replicated, with some variations, for three other major communications buildings: AT&T Long Distance, Western Union, and New York Telephone Long Island Area Headquarters. Rather than describe these four buildings in depth, we are focusing on one aspect of each to illustrate four key elements of the Walker template: exterior ornament, interior artwork and finishes, setbacks and arrangement of building form, and facade articulation. Additionally, we are also taking a look at several of his other buildings in around and New York City, including some lesser known gems.

1. Barclay-Vesey Building

A year before the completion of the 32-story Barclay-Vesey Building, a 1925 New York Herald Tribune editorial expressed a widely held view, calling it “a beautiful composition in simple forms, and the pyramiding mass rising to the sky moves the spectator deeply.” As for its lead designer, almost overnight Walker went from being an unknown architect to a famed partner in the renamed firm of Voorhees, Gmelin, and Walker.

The challenge was to design the “largest telephone building in the world” containing telephone equipment, operators, offices, and customer areas. Walker was guided by a philosophy, that he later summarized as: “it is just as important for the architect to design a building for man to be mentally comfortable in as it is for him to design one in which he will be physically comfortable.”

As for exterior ornament, an excellent summary was provided by architecture critic Lewis Mumford, who wrote in The New Republic that “Mr. Walker has turned the lower stories into a rock garden, giving to the panels over the entrances, and to various other appropriate spots, a free naturalistic covering of birds, beasts, flowers and children.” Mumford paid Walker a rare compliment with the following comparison: “Louis Sullivan used ornament in much the same fashion on his early skyscrapers, but not always so successfully.”

In 2015 the upper floors were converted to luxury residences under the name 100 Barclay, while New York Telephone’s successor, Verizon, continues to occupy the lower floors. The conversion and historic restoration was carried out by a team including Ismael Leyva Architects and DXA Studio.

Ornament along the Guastavino vaulted pedestrian arcade on Vesey St.

2. AT&T Long Distance Building

The 26-story Long Distance Building was completed in 1932 but was actually an expansion and re-cladding of an older New York Telephone facility. It is located just south of Canal Street and was critical for improving telecommunications nationally and abroad.

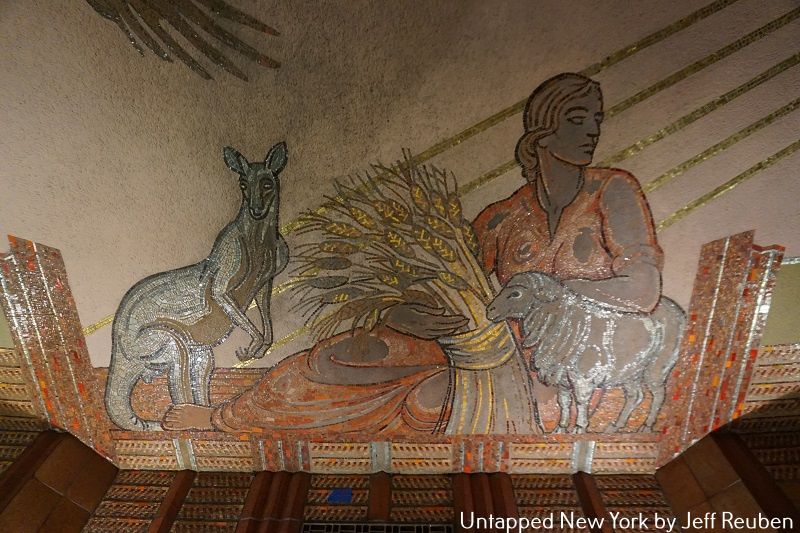

Unlike his bête noire, Le Corbusier, Walker was not the heroic lone genius type. As he once remarked, “I am the analyst of beauty, so to speak, but the final design is the work of many minds, each contributing something to it.” This is evident in the Long Distance Building lobby where credit for the attractive artwork goes to muralist Hidreth Meière.

On the ceiling, she created Continents Linked by the Telephone and Wireless, a silhouette mosaic with golden lines connecting allegorical figures representing communication and the continents. It is accompanied by a tile wall map earnestly proclaiming that “Telephone Wires and Radio Unite to Make Neighbors of Nations.” The motif continues with lines on the floors and walls and also fits in well with the angular Art Deco exterior.

Now known by its address, 32 Avenue of the Americas, the building functions as a data center, capitalizing on its legacy as a communications infrastructure hub. The lobby is a designated New York City Interior Landmark.

3. Western Union Building

“Like a warm colored rose in drab surroundings”: The Western Architect magazine

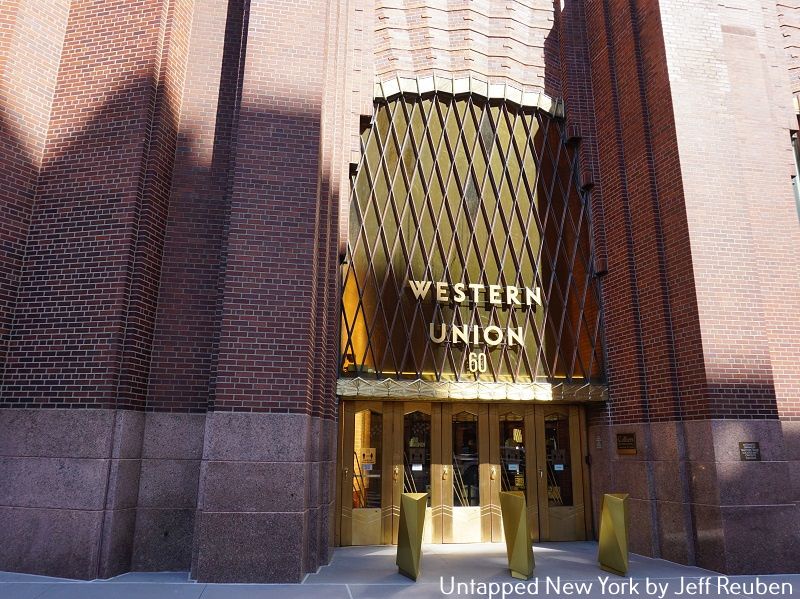

Voorhees, Gmelin, and Walker was the logical choice when Western Union Telegraph Company needed a new headquarters in the late 1920s. Although the company was not part of the Bell System, it had once been owned by AT&T and still occupied space in AT&T buildings. With both companies growing and shared tenancy no longer viable, Western Union acquired a full block site at 60 Hudson Street, close to the Long Distance Building, for construction of a new home.

Completed in 1930, the 24-story Western Union building has a series of setbacks as it rises, in compliance with New York’s 1916 Zoning Resolution. But, rather than a cookie cutter application of the zoning requirements, The Western Architect magazine (no relation to Western Union) noted that “this building is distinctive in the slight variations in the planes of the wall surfaces in the upper parts.” This was one of Walker’s trademarks; delicately using asymmetry to avoid monotony.

Attention to the arrangement of building form is also reflected in the main building entrance. Walker had a basic formula, customized for each project, which as demonstrated by Western Union consisted of slightly recessed portals with distinctive facade treatments such as patterned metalwork over glazing above the doors.

Although Western Union departed decades ago, 60 Hudson Street is now used for offices and as a data and telecommunication center. Along the building’s West Broadway side, there are display windows summarizing the original occupant’s history.

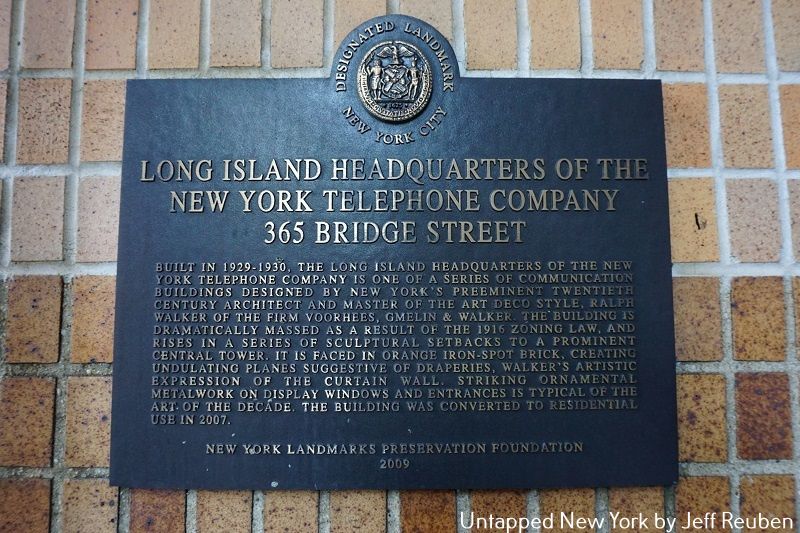

4. New York Telephone Long Island Headquarters

Walker designed a new 27-story headquarters for New York Telephone’s Long Island service area, which opened in 1931 at the corner of Willoughby and Bridge streets in Downtown Brooklyn. The exterior is almost entirely brick-clad with interspersed shades of yellow, orange, red, and brown, arranged to provide a lighter tone at upper portions, similar to an aesthetic effect used at Western Union. This curtain wall uses brick patterning, including vertical projections and recesses imparting a sense of rhythm and motion.

Although the term “curtain wall” later became synonymous with external building skins of glass and metal, it originally referred to any vertical building enclosures that are not load bearing. At the Long Island Headquarters, the walls actually resemble the rippled shape of curtains, a feature common in Walker buildings though especially well executed here.

This building was restored and converted to luxury condominiums in 2007, according to plans by architects Beyer Blinder Belle. Renamed Belltel Lofts, it was the first in what has become a trend of Walker residential conversions.

5. Walker Tower

Although prominent in his prime, Walker had somewhat faded into obscurity until the partial conversion of this telephone exchange building to luxury condos in 2012. Located on West 17th and 18th streets in Chelsea, this 23-story building, originally constructed in 1929-1930, was rebranded Walker Tower and its developer, JDS Development Group, sponsored the publication of the monograph Ralph Walker: Architect of the Century by architectural historian Kathryn E. Holliday, and hosted a related exhibition on-site.

While Verizon still occupies parts of the 23-story building, architects CetraRuddy carried out a modernization of the facade and conversion of the lobby and upper levels, combining historic preservation and restoration with alterations such as increased window sizes to better accommodate residential use.

The most visible change is a new metal crown, which is inspired by unrealized plans Walker had for a distinctive building cap. Any expense for that elaborate addition paid off handsomely, as the penthouse sold for $51 million. A great result for the building but not so much for the purchaser, who, it turned out, paid for it with dirty money and now is serving a prison term.

W. 17th Street entrance (still used by Verizon)

6. Stella Tower

The winning formula established by the Walker Tower was replicated by the same team in 2014, when they converted another Ralph Walker telephone exchange from 1930 and named it Stella Tower, in honor of Ralph’s first wife. This 18-story building, located on West 50th and 51st streets in Hell’s Kitchen, is a bit shorter than Walker Tower but otherwise nearly its twin both in its original treatment and transformation. The Walker Tower appeared in an episode of Billions, standing in for the exterior of a secret art storage facility .

While these buildings epitomize sophisticated Art Deco urban living, it may come as a surprise that their namesakes were suburban traditionalists. For over forty years the Walkers lived on Roaring Brook Road in Chappaqua, Westchester County. Their property, given the bucolic moniker Walkerburn, included a historic stone barn, wood shed, and contextual stone extension designed by Ralph, surrounded by gardens tended by Stella.

When asked why he used a conservative approach for his own home, Walker told a New York Times reporter in 1931 that he designed it “for the client,” that is to say, Stella, who was not partial to modern styles.

7. Other Telephone Buildings

NY Telephone Nassau-Suffolk Division Headquarters, Hempstead, LI

Besides the showcase projects in Manhattan and Downtown Brooklyn, Walker and his firm also designed a number of other telephone buildings. Even with lesser budgets and lower profiles, he incorporated distinctive elements consistent with his template.

NY Telephone Exchange Building, 200 E. 13th Street, Manhattan

For example, when the nine-story New York Telephone Nassau-Suffolk Division Headquarters opened in Hempstead in 1931, a local newspaper reported that “it represents an adaptation of metropolitan skyscraper architecture to suburban surroundings and resembles in many characteristics” the Barclay-Vesey and Long Island Headquarters buildings.

New Jersey Bell Headquarters, Newark (sculpted frieze by Edward McCartan)

Walker showed that his template could be scaled to a range of sizes and sites. This includes the 21-story New Jersey Bell Headquarters in Newark (1929), a four-story telephone exchange at Avenue U and W. 12th Street in Brooklyn (1928), and an expansion — from three to 11 stories — of a telephone exchange building at the corner of Second Avenue and E. 13th Street in the East Village (1930).

NY Telephone Exchange Building, Avenue U & W. 12th Street, Brooklyn

The Second Avenue facility experienced a devastating fire in 1975 that cut service to 170,000 phone lines. Despite major equipment damage the building survived intact, a testament to its durability.

NY Telephone Nassau-Suffolk Division Headquarters, Hempstead, LI

Most of these buildings are still used by Verizon, but the old New Jersey Bell Headquarters recently became the latest to be adaptively reused and is now called Walker House, with market rate and affordable housing units and ground floor commercial space. Perhaps Walker’s most under appreciated work, it will soon house a microbrewery, Newark Local Beer, opening this winter.

8. Salvation Army Buildings

In a departure from his usual clientele, in 1928 Walker designed a three-building complex for the Salvation Army. Completed in 1930, it includes a 17-story residential tower at 123 West 13th Street, which is connected at its lower levels to an 11-story Administration Building and a lower-rise auditorium; the latter two face West 14th Street.

Although it follows his template, here Walker applied ornament more sparingly. It seems a good fit for a religious organization known for its charity work and which is unconventional compared to traditional denominations; Modernistic but unpretentious.

Buildings at left are by Walker; building at the right is a later addition

The most striking part is the low-rise Centennial Memorial Hall. True to Walker form, it has a monumental entry portal, in this case featuring a high staggered arch. There is a wide landing, a few steps above the sidewalk, from which twin L-shaped staircases rise on each side to the main theater.

The Salvation Army still occupies these buildings (no luxury conversions here), though the residential building, originally limited to “young business women,” now houses “men and women studying, interning or working.”

9. Irving Trust Building

This building, for a leading New York bank that borrowed its name from legendary writer Washington Irving, can be seen as the pinnacle of Ralph Walker’s golden run of architectural mastery. To purists, it is his only true skyscraper, a slender and soaring 50 stories tall.

His work here suggests a refinement of his style that might have developed further were it not for economic realities. Designed in the boom times of 1928, the Irving Trust Building at 1 Wall Street opened its doors in March 1931 amidst the deepening woes of the Great Depression. After the early 1930s, Walker never completed another of this kind.

Inside, the bank money paid for extensive and elaborate decorations. Limitations of space do not permit a full inventory, but the Roaring ’20s zeitgeist was reflected in a lobby fresco by Hildreth Meière and Kimon Nicolaides which Irving Trust called the “Power of Wealth to Create Beauty.” An alternate title, “The Only Reason for Wealth Is the Attainment of Beauty,” seems to have been favored by the artists. (In the 1960s, an age with different values, it was sacrificed for the installation of air conditioning ducts.)

On the exterior, Walker used concave bays, with the limestone facade and windows gently curing inward. This element, akin to the fluting on a Doric column, combined with his subtly asymmetrical setbacks, produces an almost subconscious texture. He once again achieved what he did at Barclay-Vesey, making a monumental building that is not monolithic, but this time relying less on ornament.

Walker himself acknowledged this in a 1930 speech. “The mistake we made on the Telephone Building was that we placed too much decoration in certain places. In this new [Irving Trust] building the design is actually readable.” Alas, Walker’s old fan Lewis Mumford disagreed. Writing in The New Yorker, the then young curmudgeon jeered “chaste though that exterior is, it is mere swank, and unconvincing swank at that.”

The building, now known simply as One Wall Street, along with its 1960s annex to the south, is currently being converted to luxury residences above a retail base.

10. Later Years

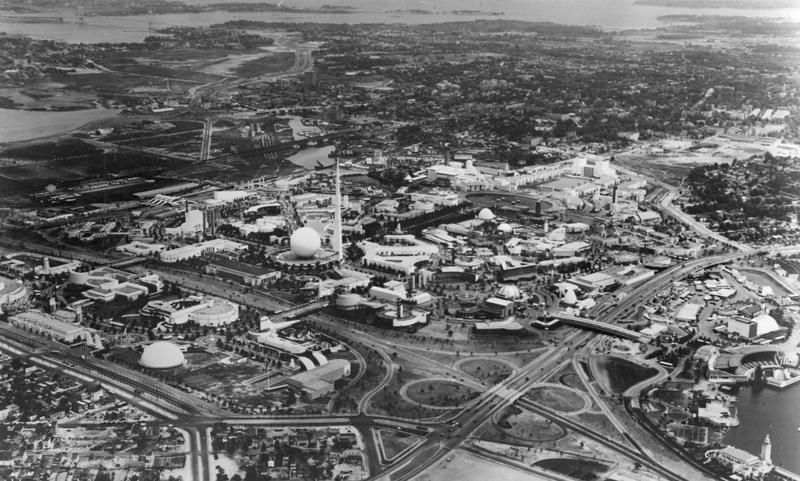

1939 World’s Fair. Photo Courtesy of NYC Parks Archives

As the Great Depression wore on, business nosedived for Voorhees, Gmelin, and Walker and, as a result, the firm went from a staff of 300 in 1928 to 25 in 1931. Its few major commissions in those years included world’s fairs, including 1933 in Chicago and 1939 in New York, where Walker designed pavilions that were notable but ephemeral.

[post_featured_tour]

After the 1930s, as Art Deco faded and was supplanted by austere Modernism, the workload rebounded but Walker never again reached the same heights. Later projects, such as the headquarters of General Foods Corporation in White Plains (1954), were well received but unlike his earlier works did not capture the spirit of the times.

General Foods Corporation. Public domain image via Wikimedia Commons

Rhetorically, Walker did not go gently into that good night. In 1957, he wrote that “I think our present-day reluctance to use sculpture, painting and decorative ornament is a blind spot caused by the extremely stupid concepts, promulgated by a few but influential Europeans.”

In spite of swimming against the tide, that same year the American Institute of Architects awarded him the Centennial Gold Medal. He was “chosen for the unstinting use of his talents and energies in many fields of public service,” a contrast to his cantankerous peer Frank Lloyd Wright. But even FLW reportedly called Walker “the only other honest architect in America.”

Walker retired from full time work in 1959. After Stella died in a nursing home in January 1972, he married his second wife, Christine, a widow, at his home in Chappaqua two months later. The following January, at age 83, Ralph Thomas Walker took his own life (reportedly due to a brain cancer diagnosis), a somber coda to an accomplished and inspiring life.

Next read about the residences in the Barclay-Vesey Building, see Construction Photos Inside the Stunning 3-Story Penthouse of One Wall Street, and learn more about the lobby of the Barclay-Vesey Building.