Standing proudly at Brooklyn’s Grand Army Plaza, the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Memorial Arch acts as both a monumental entrance to Prospect Park and as a threshold between some of the borough’s most stately neighborhoods like Park Slope and Prospect Heights. But when it was constructed, the eyes of the city were oriented northwards towards the center of gravity that was Manhattan and Downtown Brooklyn. As Prospect Park Alliance architect Alden Maddry explained to us on a recent exploration inside and atop the magnificent Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Memorial Arch, when Prospect Park first opened in 1867, it was considered the frontier of the borough. “Basically everyone was coming from that direction,” he says, pointing north in the direction of the skyscrapers in Downtown Brooklyn, “Everyone lived toward Manhattan and Brooklyn Heights at that time, so everyone was coming this way.”

The Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Memorial Arch (along with Grand Army Plaza) is in the beginning of a long-awaited $8.9 million restoration led by the Prospect Park Alliance and NYC Parks, and funded by the City of New York. The unveiling of the plans prompted our special access visit with flashlights in hand, walking up the crumbling spiral staircase and ending with the wind whipping at our faces between the bronze sculptures on top.

Prospect Park architect Alden Maddry in front of the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Memorial Arch

Most of the restoration efforts are focused on the arch, which has suffered from leaks and structural damage over the years (not to mention graffiti vandalism). One of the city’s great secret spots, the Puppet Library once showcased its giant parade puppets in the arch’s former trophy room, but it relocated to Brooklyn College when the roof started leaking. Public access inside the arch has been closed off since, but the latest restoration work will allow visits inside the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Memorial Arch on special occasions (akin to how we visited the top of the Washington Square Park Arch with NYC Parks Commissioner Mitchell Silver in 2019).

While this is not a professionally produced video, we thought readers would like to see some of our video clips inside which we took for research purposes.

The latest restoration of the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Memorial Arch will include replacing the roof, repointing 20,000 linear feet of mortar joints between the exterior granite blocks, repairing interior elements like the historic spiral iron staircases, and adding new lighting inside and on the outside. The lighting scheme, designed in partnership with Renfro Design Group, which also worked on the Lefrak Center rink in Prospect Park, will showcase “the historic elements of the arch and its statuary while making the lighting more environmentally friendly by utilizing energy efficient technology,” according to the Prospect Park Alliance. On our visit, light strips were affixed on the interior staircase as a test for what could be.

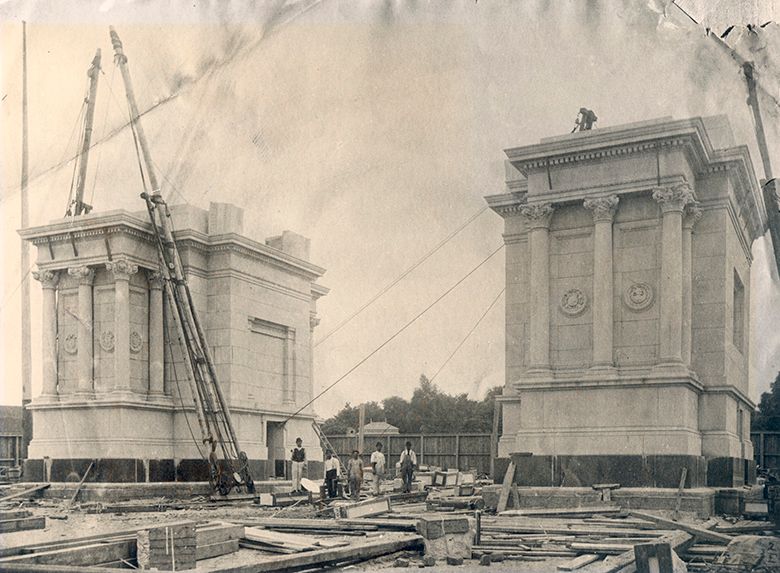

The two piers of the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Memorial Arch under construction, circa 1890. Photo courtesy of Prospect Park Alliance.

The two piers of the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Memorial Arch under construction, circa 1890. Photo courtesy of Prospect Park Alliance.

The Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Memorial Arch was built starting in 1889 as a commemoration to those who fought for the Union during the Civil War, with its cornerstone laid by General William Tecumseh Sherman. The granite and brick arch was dedicated in 1892 with U.S. President Grover Cleveland present at the ceremony. The various Brooklyn regiments involved in the Civil War are symbolically shown on the decorative medallions on the arch, and you can imagine how such an honor would have been a point of pride for those who fought nearby, like the 14th Regiment of the New York State Militia (most famously nicknamed “The Red-Legged Devils” by Confederate General “Stonewall” Jackson in the First Battle of Bull Run), headquartered in the Park Slope Armory.

Medallions on the arch represent local regiments that fought in the Civil War

The Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Memorial Arch was designed by architect John Hemingway Duncan, who won a competition for the arch. The commission formed to create the monument stated that they selected Duncan’s plan with “no hesitation” and that it was “the best among” the 36 entries submitted. In fact, the commission contended that it was the only design which was “at the same time suitable, in its general conception and character, to the position and purpose in view, and also shows such technical and artistic merit as to redeem it from the commonplace….The design, while belonging to the established type of memorial arches, has a marked individuality and resembles previous examples less than, in general, they resemble each other.” Duncan was awarded $1000 and the Brooklyn Daily Eagle was excited to announce that a New Yorker won the prize. Duncan would become most famous for designing Grant’s Tomb in Manhattan.

The arch would later receive more ornamentation, under the direction of Stanford White when the firm McKim, Mead & White was hired to rework the entrance to Prospect Park. Stylistically, the arch was a sharp departure from Olmsted and Vaux’s rustic style — think of the dairy building in Central Park or the now-lost thatched shelter in Prospect Park. Maddry believes that Olmsted and Vaux wouldn’t have liked the aesthetic at all, but “at some point styles change,” he acknowledges.

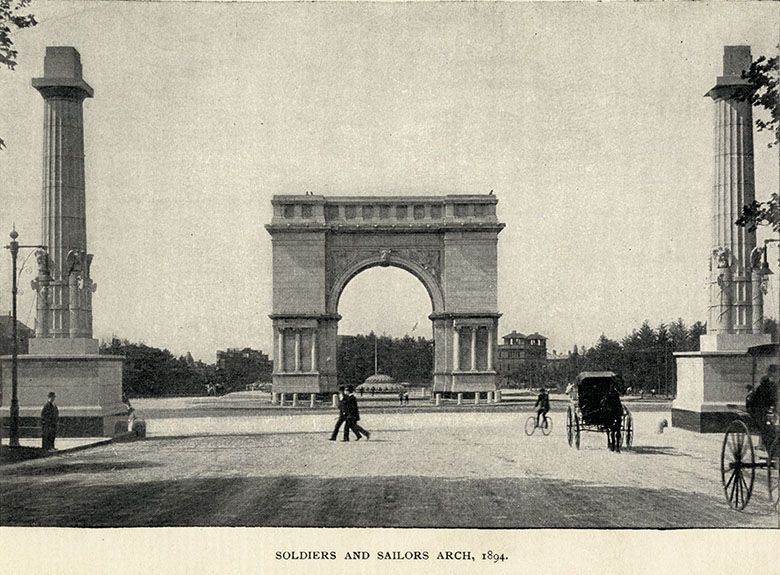

Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Memorial Arch in 1894. From the 34th Annual Report of the Brooklyn Park Commissioners 1894. Photo courtesy of Prospect Park Alliance.

Maddry explains that this late addition of the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Memorial Arch to Grand Army Plaza led to some debate as to where it should be located. “This wasn’t the only place that was considered,” Maddry says. The memorial commission also expended quite a bit of their announcement discussing the location, requesting that the arch “stand alone at the end of the Plaza. In other words,” they write, “it should be a monument not a gateway” and that it should be “isolated.”

A predecessor fountain to the one today was already in the plaza, so the arch could not be located further north where Flatbush Avenue ends at Grand Army Plaza. Funny enough, the producers of the recent Netflix show Grand Army took this conundrum into their own hands, photoshopping the Soldiers and Sailors’ Memorial Arch to that spot and flipping it around so that the arch can be seen clearly, with all its sculptural groupings, from the north on Flatbush Avenue. Former NYC Park Ranger Anne Reid, who used to give tours of the arch, tells us that “the whole arch faces south [because] should the South ever rise again, we are ready.”

Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Memorial Arch complete, after 1905. Photo courtesy of Prospect Park Alliance

When Stanford White was redesigning the park entrance, he also suggested that the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Memorial Arch get its own update to fit in with the new City Beautiful movement that took the country by storm following the 1893 World’s Colombian Exhibition in Chicago. The sculptures, which include the two groupings of soldiers on the south pedestals, the quadriga with the goddess Columbia on a chariot representing the United States, and the winged Victories flanking her, were created by Frederick MacMonnies on a commission from the Parks Department. MacMonnies also designed the main fountain for the World’s Colombian exposition, the much-maligned Civic Virtue for City Hall Park, and the statue of General Slocum at Grand Army Plaza next to the arch. He was partially influenced by the monumental ornamented arches of Paris, especially the Arc de Triomphe, from the decades he spent living, studying, and working in the city. He apprenticed for Augustus Saint-Gaudens, and fortuitously met Stanford White in Saint-Gaudens’ studio.

The Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Memorial Arch was landmarked in 1973, but according to the Prospect Park Alliance, the arch was in “severe disrepair” at the time of its landmarking, and the Columbia statue “literally fell from her chariot” in 1976. As such, this is by no means the first restoration of the arch. It was first restored from 1977 to 1979 by the city, with more work done in 1989 and in the mid-1990s. The statues were restored in 1999 through the NYC Parks Monuments Conservation Program.

However, this does mark the first time that a detailed scan has been made of the arch, executed by the structural engineering firm Atkinson-Noland & Associates using radar and magnetic investigation. This has been particularly helpful since the original blueprints of the arch were lost long ago. The inner construction of the arch and its internal condition have been revealed in a way not possible before.

Going behind the NYPD barriers

From here, we’ll take you on a visual journey from the front door of the arch all the way up to the top. The original arch featured iron gates in front of the doors, which allowed air flow into the arch while still closing off the interior to the overly curious passerby. This architectural detail will be brought back in the latest restoration.

When you first walk inside, you’ll be greeted by a metal plate on the floor emblazoned with the name KosmoCrete, a type of proprietary concrete from the Brooklyn-based Wilson & Baillie company. The firm was located in Gowanus just a few blocks from the Coignet Stone Company, which built one of the earliest known concrete buildings in New York City as their headquarters. Wilson & Baillie specialized in making concrete pipes (along with manholes, steel gutters, curbs, sidewalks and more). Kosmocrete, says Maddry, was the company’s “own special mixture of concrete and it was used in the Brooklyn Navy Yard and Wallabout Bay.” The company cast branded metal plaques in four places inside the arch, which we happily rediscover 131 years later.

The entrance vestibule of the arch, about two stories high, is currently used for storing various Parks Department items used for for events on the plaza. Two cast iron staircases spiral up from this antechamber. One of the strangest items here is a full-sized maquette for a bronze sculpture, stuffed under the north staircase, which Maddry once confused for a real-life body while field measuring the arch. “That made my heart race for a little while, because usually I’m in here alone,” he says.

The interior masonry of the arch is brick, but various coatings have been placed on top of it over the years, “a lot of them inappropriate that don’t breathe so it really seals the water,” says Maddry. The plan is to remove as much of the coatings as they can. Tests of the cleaning and conservation processes that will be used on the arch have already started, led by The Karcher Company.

Testing has been done here on how to remove the coating on top of the brick.

The spiral staircases are actually made from a mix of cast iron and wrought iron, which are used for the curved pieces. It’s not feasible to source wrought iron anymore, so they will likely be replaced with steel. The most damaged pieces of the staircase are those attached to the brick wall, and to replace those sections, the entire staircase will need to be unstacked and then reassembled. Each piece of the staircase is stacked on the one below, so work will need to begin from the top down. The engineering firm Thornton Tomasetti, whose motto is “When others say no, we say ‘Here’s How'” was hired to consult just on the staircases. “It’s going to be interesting,” says Maddry understatedly of the staircase restoration, “just the cast iron repair is its own thing.”

The ornamentation on the base of the staircase shows a fasces, the Roman symbol with an axe surrounded by a bundle of sticks. While it has historically been used as a symbol of governance, it was co-opted by the Fascist movement in the 20th century in both nomenclature and symbolism.

The ornamentation on the base of the staircase shows a fasces, the Roman symbol with an axe surrounded by a bundle of sticks. While it has historically been used as a symbol of governance, it was co-opted by the Fascist movement in the 20th century in both nomenclature and symbolism.

We continue up the dark stairwell with our flashlights. Corroded pipes hang off the walls, the stucco on the wall and the wrought iron on the staircase flake off at the lightest touch. Sometimes a step or landing is completely broken, so we have to hop over to a safer step. In some spots, the iron handrail has broken off or a baluster is missing.

There are a series of platforms on the way up to the top of the arch. The two first staircases end at one, and the trip continues up another spiral staircase which begins on this platform. Fortunately, these upper staircases can be fixed in situ without a complete disassembly like the lower staircases.

The first landing inside the arch

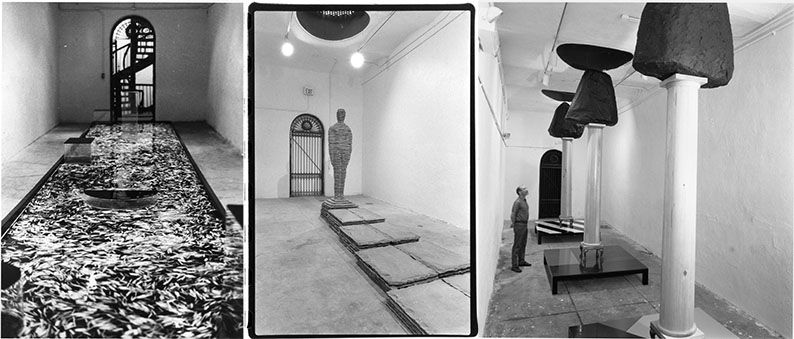

Atop the second spiral staircase is the grand trophy room, 14.5 feet tall and 44 feet long, intended to be a museum to the Civil War. It was never used as a trophy room, as far as the Prospect Park Alliance knows, but it has been used for art exhibitions and for the aforementioned Puppet Library. You enter this grand room through one of two ornamented iron doors. Above the transom, the letters U.S. (United States) are placed within a wreath.

The roof of the trophy room is made of vaulted brick set between steel beams, something you see in some subway stations in New York City. The beams are rusting so new beams made of steel will be added to support the room. Three skylights in this room once let in natural light and are made of a collection of circular glass bulbs, much like the vault lights on Soho sidewalks. At some point after the Columbia and Victory statues were added atop the arch, an additional roof was constructed that shut off the light source. This secondary roof will stay in this restoration, as “it actually is good for preventing the water” from coming into the arch, says Maddry.

Our voices echo in this room, while Maddry tells us about the steel beams they discovered through the radar scan. There are seven that extend under this room — something nobody knew existed until recently. Their existence was doubly confirmed after drilling a few holes and inserting a boroscope to see the beams up close and assess their condition.

Art exhibitions inside the Trophy Room. Left: 1985 exhibition artist unknown. Center: Work by Boaz Vadia in 1985. Right: 1988 exhibition called “Pillar to Post: The Sculptural Column.” Artist Eliot Lable with his massive columns. photos courtesy Prospect Park Alliance.

From the trophy room, you can get up the roof from one of two spiral staircases, one on each end of the arch. There’s a hatch at the top, which you have stoop down in order to get out. From there, you get a 360 degree view of Brooklyn, from Prospect Park to Park Slope, Downtown Brooklyn, Prospect Heights, and east towards Crown Heights. You can also see the Lower Manhattan skyline.

The roof needs a little love, and will be getting it in this restoration. The roof membranes all failed long ago, and Maddry shows us a small spot where they cut out a section of the roof to investigate. The restoration will see to the removal of all the roof membrane down to the structural deck with new, more water resistant roofing placed on top. Gone too will be the phragmites, an invasive wetland reed that has taken root deep in the roof, proliferated, and blocked the drains.

The phragmites growing on the roof

Test of the roof membrane from seven years ago, all the layers are waterlogged.

Up here, you can also see statues of Columbia on her chariot and the two statues of Victory up close, and we took the metal staircase to go between and under the sculptures. It’s quite the foot-tingling view. MacMonnies cast the sculptures in Paris and had them shipped to the United States. His Horse Tamers sculpture, also located in Prospect Park, actually went down in a shipwreck off Newfoundland and was recovered and then repaired. From this vantage point, you can see the level of detail within the bronze. MacMonnies sometimes sculpted his horses from live models and the attention to the animals’ muscular forms is clear. Former NYC Park Ranger Anne Reid told us that the horses are “running in different directions, in order to spread the news of the Union Victory.” The chariot has the United States Motto, E PLVRIVUS UNUM (out of many one) on it below an eagle.

Restoration work is always a long, detailed-oriented project that takes a village. Although the plans to restore the arch were unveiled in November 2020, Maddry started looking at the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Memorial Arch about eight years ago. “It’s been a while,” he said, as we climbed up the last of the spiral staircases. If there is anybody who knows the necessity of restoring the arch as soon as possible, it’s Maddry who adds, “The Arch has been gradually deteriorating since it underwent its last major restoration forty years ago and key elements such as the roof and the iron stairs need a major overhaul. It’s wonderful that the city and the Mayor have funded this much needed restoration.” Still, the public will have a few years to wait as construction on the arch should begin in late 2021 or early 2022, and completed in 2023.

When all is done, no stone will have been left unturned by Maddry and his team. The Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Memorial Arch will be restored to its earlier glory (albeit not its original iteration of course) with modern touches, some hidden to the naked eye. The arch will once again be able to welcome visitors, like it was intended — no small feat in this world, especially in New York City where access is more often shut down rather than opened up. Prospect Park, a public park considered by Olmsted and Vaux to be their masterpiece, has entered a new era of civic building with restorations not only to the arch, but also to the Endale Arch and the Concert Grove Pavilion, the opening of a new entrance on Flatbush Avenue, new permanent art installations, and more. The restoration of Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Memorial Arch and Grand Army Plaza definitively signals this renaissance for Prospect Park, an open space ever more important to New Yorkers today as we near the one year anniversary since the beginning of the pandemic.

Next, take a look inside and atop the Washington Square Park Arch. Read about the secrets of Prospect Park.