We’ve been following the story of 227 Duffield Street on Abolitionist Place in Downtown Brooklyn for over a decade, when we first learned about the Underground Railroad-connected building in a 2007 lawsuit pertaining to the construction of what was then called Atlantic Yards. The house was among a row of historical homes built in 1848, nearly two decades before the Civil War, that residents believed were connected by tunnel and used to transport escaping slaves along the Underground Railroad. Over the last decade, all the other buildings were demolished, but 227 Duffield Street remained. Last August, we reported on the demolition permit that had been filed for the building, along with an application to construction a new 13-story building. Yesterday, in a hard-won victory over fifteen years in the making, 227 Duffield Street was officially landmarked by the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission.

Underground on Duffield Street, a trap door, exit shafts, covered wells, and other “architectural anomalies,” were used to substantiate the Underground Railroad claims that were at the basis of a 2007 lawsuit between FUREE (Families United for Racial and Economic Equality) and the City of New York, which wanted to condemn the properties to support the redevelopment of the area which has become Pacific Park. In 2007, that stretch of Duffield Street was re-named Abolitionist Place in reference to the history but the buildings remained unlandmarked.

227 Duffield Street was once the home of Thomas and Harriet Truesdell, staunch abolitionists who moved to the house in 1850. Thomas was a delegate at the Rhode Island Anti-Slavery Convention, Harriet was treasurer and secretary of the Providence Female Anti-Slavery Society and a delegate and committee member of the Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women in 1838. Just nearby, Underground Railroad conductor William Harned lived at the intersection of Duffield and Willoughby streets.

The tunnels underground are thought to have once led to the Bridge Street African Wesleyan Methodist Episcopal Church (today Wunsch Hall at Polytechnic University), another Underground Railroad stop and Brooklyn’s first African-American church. And not far away was the most famous of the Brooklyn Underground Railroad locations, Plymouth Church, nicknamed the “Grand Central Depot” of the Underground Railroad system. Proximity to the waterfront in Brooklyn was key for the Underground Railroad, as we have seen for the Lott House in southern Brooklyn which would convey escaped slaves onwards towards places like Weeksville in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, one of the largest free black settlements in the United States before the Civil War, and further north. In its official press release about the landmarking of 227 Duffield Street, the City of New York states that the waterfront served “as an “entry point for many freedom seekers who stowed away on ships to escape slavery in the south; many of them were sheltered by local abolitionists and either stayed in Brooklyn or traveled north to Upstate New York, New England; or Canada.”

Photo by Justin Cohen

Yesterday’s celebration of the landmarking of 227 Duffield Street involved both a community event in front of the home attended by Mayor Bill de Blasio and his wife Chirlane McCray. Another event took place inside City Hall. Although not required legally, the Landmarks Preservation Commission usually seeks buildings of architectural merit, and has deemed 227 Duffield Street “a rare surviving 19th-century abolitionists’ home in Downtown Brooklyn,” adding that “While a two-story commercial extension was added in 1933, the house retains its 19th-century form and historic fabric above it, and its significant association with the Truesdells and the history of the abolition movement in Brooklyn prior to the Civil War is still legible.”

Shawné Lee, daughter of Mama Joy Chatel at the landmarking event at City Hall. Photo by Justin Cohen.

The Truesdelles lived at 227 Duffield Street until 1921. Fast forward to the 2000s, and its owner Joy “Mama Joy” Chatel spearheaded the effort to raise awareness of the house’s history. For a period of time, she ran a museum from the building, the 227 Abolitionist Place Museum and Heritage Center. She told the New York Times before her death in 2014, “there’s no black museum in Brooklyn to celebrate the Underground Railroad. This is the house to do it in. It’s important that the children and all of the people can see what people had to go through to be free.”

The storefront in 2016 when it still contained information from the 227 Abolitionist Place Museum and Heritage Center.

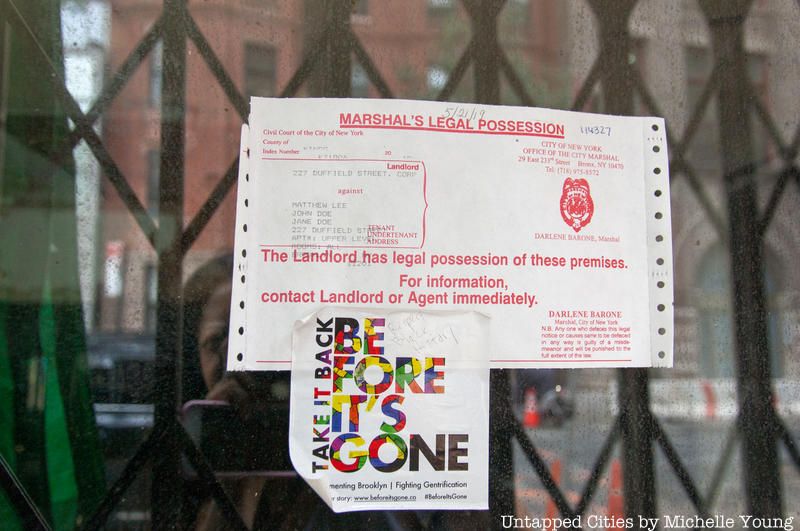

The story of what happened to the house after Mama Joy’s death is a classic Brooklyn real-estate story. Actors of dubious intent sought control of the house, “mirroring the pattern of deed theft that is being catalogued throughout the borough,” wrote Justin Cohen who ran last fall for New York State Assembly in Brooklyn District 56, and has been actively involved in Friends of Abolitionist Place, an organization that grew out of the struggle to save 227 Duffield. That organization plans to partner with the city to transform the building into a “Heritage Center.” Under the company 227 Duffield Street LLC, developer Samiel Hanasab purchased the building for a total of just $649,000, while neighboring buildings had sold for $3 million to $10 million dollars. $149,000 went to the family of Joy Chatel and $500,000 to an investor named Errol Bartholomew who purchased a 50% stake in the house from the Chatels when they needed the cash.

Today, Cohen tells Untapped New York, “One of the most striking ways that white supremacy manifests is in the visible decisions we make about which history we valorize, versus what we choose to sweep under the rug. Look around New York City. There are hundreds of streets named after families who owned enslaved people. Meanwhile, the city fought tooth and nail to destroy this one house that carries the history of abolition and the tradition of radical Black liberation.”

Photo of the landlord action against tenants at 227 Duffield Street in May 2019

At the event yesterday, Mayor Bill de Blasio said, “The battle for justice in this country always has been – and always will be – fought in the heart of New York City. Black History Month in this city means more than just words. It means honoring the legacy of the Black New Yorkers who came before us. I’m grateful to every advocate and community leader who made this day possible, and this city will continue to stand with you in the future.”

First Lady Chirlane McCray said eloquently, “We may not know the names of the African souls that traveled in secrecy and desperation through downtown Brooklyn in search of a better life, but we do know this is one of the many sites that served as a temporary haven as they sought freedom. We also know that the residents of 227 Duffield Street risked losing power, respect and even their lives by helping those who were fleeing enslavement. These stories of our history need to be celebrated, not erased. It is an honor to highlight these sacred passages of our ancestors.”

227 Duffield Street and Abolitionist Place are included in our book Secret Brooklyn. Next, check out the 33 black history sites to discover in NYC.