The Berkshires Bowling Alley that Inspired "The Big Lebowski"

It’s been 36 years since the release of The Big Lebowski, the irreverent cult comedy by Joel and Ethan

A historic house in Washington Heights that once belonged to abolitionist Dennis Harris might be demolished and replaced by a 13-story residential building. The home is the city’s last connection to Harris, a prominent activist in the fight for racial equality, an ally of the Women’s Suffrage Movement, and a conductor of the Underground Railroad.

At the end of January, Manhattan Borough President Gale A. Brewer, State Senator Robert Jackson, and several other elected officials stood at 857 Riverside Drive and called on the city to delay the demolition permit and reverse their rejection of landmark status for the home. The residents of Washington Heights have also voiced their disagreement with the demolition on saveriverside.org, with resident Matt Hong writing, “Historic neighborhoods need to be preserved and protected. Please don’t build this tower. Restore this beautiful house.” This call comes just as 227 Duffield Street, an Underground Railroad house in Brooklyn, received official landmark status from the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission.

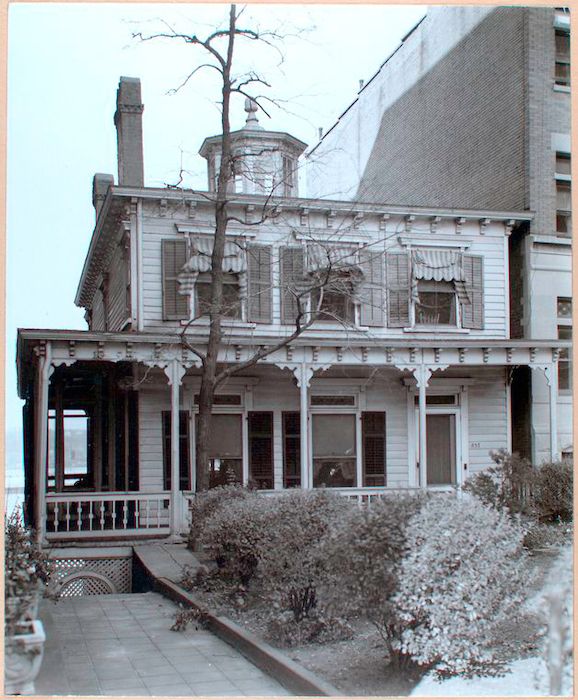

Photo by Berenice Abbott showing 857 Riverside Drive in 1937. Photo from NYPL Digital Collections.

Built in 1851, the modest two-story house sits at 857 Riverside Drive between a towering apartment building and a stretch of townhouses to the north. Though small in comparison to its neighbors, it displays the architectural history of the city, as it conjoins Greek-Revival and Italianate characteristics to represent the transition between the two movements. It is a mark of the rural neighborhood that once existed in the years leading up to the Civil War. The historic photograph above shows its original architecture architecture, with a wraparound porch, wooden shutters, widow’s peak, and sited with views of the Hudson River.

Dennis Harris, an ordained Methodist minister, immigrated to the United States from England in 1832. Strongly opposed to slavery and eager to provide for his young family, Harris worked under Samuel Blackwell, an abolitionist and sugar refiner, and the brother of Elizabeth Blackwell, the first female medical doctor in the United States. After learning the refinery business, Harris began his operation — a sugar refinery that would become a busy station stop on the Underground Railroad.

Harris bought the Washington Street sugar refinery in 1837, and a few years later he purchased the New Congress Sugar Refinery with the help of business partner Judge John Newhouse. The two also operated the Jenny Lind steamboat (named after the Swedish opera singer who performed at Castle Clinton) which they used to provide safe passage to runaway slaves in their travels up north to Canada. The slaves were sheltered in the sugar refinery and carried in the steamboat upriver from Lower Manhattan. The refinery would later move up to Washington Heights, and would lead to the construction of the house at 857 Riverside Drive.

Though the exact number of slaves that Harris helped is unknown, newspaper accounts detail his role in assisting George Kirk, one of the many runaway slaves who were protected by the Underground Railroad. Kirk was chased through the streets of Manhattan by police until he reached the Anti-Slavery Society office, where he was hidden beneath the floorboards while authorities surrounded the building. Harris sent a wagon to take Kirk, who would be stowed away in a crate with papers and books, from the office to the safety of his sugar refinery a few blocks away. Kirk had almost made it to the refinery when he was caught, but he would later be released and successfully smuggled away to Canada by the Underground Railroad.

Harris used his position as a minister to deliver sermons in support of racial justice. When he faced the loss of his ministerial position because of his stance against slavery, he broke away from the Methodist Church to support the “Wesleyan Connection” movement. Alongside thousands of other Wesleyans, Harris publicized abolitionist thought in pamphlets, raising thousands of dollars for escaped slaves living in Canada.

After a fire burned down the first New Congress Sugar Refinery, Harris moved uptown, establishing his own chapel, a new sugar refinery, and the land where the house currently sits. Harris maintained the property for two years before selling it to longtime friend John Newhouse and his large family in 1854. The Newhouse family and their descendants would live in the home for 50 years.

The original house was altered to make room for the construction of the surrounding buildings, and a stucco facade was applied to the front of the house in the 1990s to improve insulation. The wood still remains visible on the sides and rear, and Greek-Revival and Italianate motifs remain untouched, retaining the building’s 1850s country house identity. While the rest of the neighborhood has been urbanized, this home represents what the area used to be in the turbulent, historic times of the nineteenth century.

The Landmarks Preservation Commission rejected landmark status for 857 Riverside Drive on the grounds that the changes made to the building have diminished its historical significance — a long-running line that has been used to reject landmarking of other historic buildings, including the last existing home of Walt Whitman in Brooklyn. Moreover, officials and residents of Washington Heights have noted the lack of approved landmarks in communities of color. Architectural alterations have been overlooked in other landmark sites.

As Brad Vogel, the Executive Director of the New York Preservation Archive Project who founded the Coalition to Save Walt Whitman’s House, told us previously in regards to the Whitman house at 99 Ryerson Street, the Landmarks Preservation Commission’s reasoning for rejecting the landmarking is based upon a narrowed definition of the 1965 Landmarks Law which focuses almost exclusively on architectural purity. But Vogel says, the purpose of the law is clearly stated to “safeguard the city’s historic, aesthetic and cultural heritage” and protect the city’s “city’s cultural, social, economic, political and architectural history.” Under that definition, houses like 857 Riverside Drive and 99 Ryerson Street could qualify.

But as it is now, it has been more difficult for buildings in neighborhoods such as Harlem and Washington Heights to achieve landmark status. Wealthier property owners have an advantage when it comes to preserving their buildings. Many buildings have been significantly altered for various reasons, coupled with an inability of some building owners to preserve structures as they were originally built. With the house at 857 Riverside Drive being the last surviving link to abolitionism in Upper Manhattan, the Landmarks Preservation Commission is under criticism for what many believe to be unfair treatment and a systematic bias against landmarks related to abolitionism.

Next, read about 227 Duffield Street, the Underground Railroad House in Brooklyn that was just landmarked.

Subscribe to our newsletter