In the middle of Clinton Hill, Brooklyn is the 25-acre Pratt Institute campus, a gorgeous collection of landmarked buildings amidst open green space. On the first floor of East Hall (originally the Mechanical Arts Building) is the Pratt Institute steam engine power plant. As Pratt describes, it is the “oldest continuously operating, privately-owned, steam-powered electrical generating plant in the country,” and was named a National Historical Mechanical Landmark by the American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME) in 1977. The Pratt steam engine power plant is one of the 150+ locations featured in our book Secret Brooklyn.

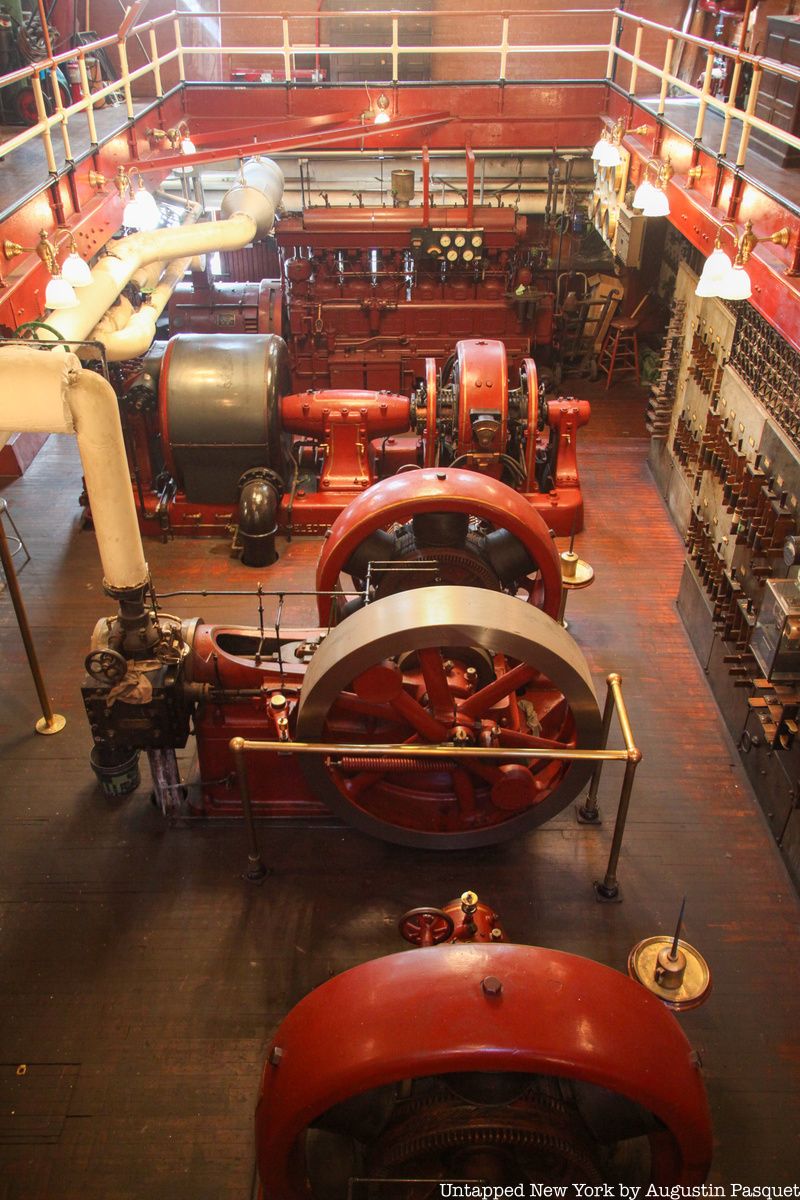

The steam generators currently in use were made by the Ames Iron Works and installed in 1900, when a campus extension required more energy. The steam engine power plant continues to power all of the Pratt campus, sending heat, steam and hot water to the buildings. The wood paneling in the lower Engine Room dates to 1887 and incandescent lights still illuminate the space.

Unlike the rest of Pratt’s campus, which was designed by the firm Lamb & Rich, the steam engine power plant was designed by William Windrim from Philadelphia. According to the report from the ASME, the original drawings for this building “called for an ‘L’ shaped building with a basement and two stories above grade, but an 1888 photo shows the North-South wing to have four stories and the East-West wing five stories above grade. At some period near the turn of the Century the North-South wing had an extra floor added to it.”

The report also states the various purveyors of equipment and technology when the steam engine power plant was built in 1887: the “Harris-Corliss Company of Providence, R. I. supplied a horizontal, 40- horsepower engine; its belt drove the machine shop equipment. Logan and Company installed two 110-HP boilers and associated piping, while the Worthington Company supplied fire and boiler feed pumps. The Custodis Chimney Company received the contract for a stack, 124 feet above grade, square at the base and octagonal from about one third its height up.”

The power plant was not yet operational when the school opened, but apparently only fifteen students had registered for the fall 1887 semester. However, everything was ready by January 4, 1888. A ceremony attended by 500 took place in celebration.

The Ames Iron Work generators were installed in 1900 to add capacity to the expanding campus. A few years earlier, The Library Building and the Household Science and Arts Building was constructed. Additional revisions to the power plant including new generators and expanded boiler rooms, were made in subsequent years, also due to the construction of new buildings. You can read a detailed account of the changes in the ASME report, but suffice it to say, the building has continued to adapt and respond to the changing power demands of Pratt’s campus, always with the aim of being economical and efficient.

This was core to Charles Pratt’s overall philosophy. “In early life he was forced to learn what it meant to economize in everything,” as reported in Scientific American in an October 1888 article about the new Pratt Institute. In fact, the ASME report states that all of Pratt’s campus was “designed on the standard mill construction of the period so that, should the school fail financially, [Pratt] had a usable commercial property.”

The steam engine power plant was designed with a wraparound interior balcony for viewing, and there have been notable relics added to the space, including chandeliers that were once in the Board of Directors room at the Singer Building, the tallest building in the world in 1908 — in 1968, it was the tallest building ever to be demolished.

A lamp comes from the Brooklyn Academy of Music basement, the chandeliers “on loan from the Munaco clock company, which acquired them from the Marine Underwriters Association in New York,” and other artifacts from industrial sites all around the country, ASME writes that the Chief Engineer’s office has been gradually “periodized,” a decor move undoubtedly by former Chief Engineer Conrad Milster, an avid collector of mechanical artifacts (and cat lover).

Milster, a New York native, has been working at Pratt since 1958. He was one of only four chief engineers in the history of Pratt Institute and saw himself as the keeper of the power plant’s secrets – know-how on antiquated technologies he has garnered over the course of nearly sixty years. “Making parts is interesting, there’s a sense of fulfillment,” Milster said in a 2015 video interview. “It involves a lot of problem-solving…A lot of the machinery I have to deal with is obsolete, insofar as spare parts. A lot of people would say, ‘Why do you have old machinery?’ I have it and I like it because it’s reliable.”

Milster said that working for a school allows him to stay true to himself: “You can be different and not be considered an oddball.” Milster also ran an annual New Year’s Eve steam whistle blow at Pratt — the last event took place as the world rang in 2015.

In 2016, it was reported that Milster, now in his eighties, had been reassigned to another area in the facilities department, allegedly over controversy over his care of the numerous stray cats that lived (and stayed warm) in the Engine Room. The power plant once had an adorable entry portal just for the “Pratt Cats,” labeled the “Feline Staff Entrance.” Milster was even given an eviction notice from his campus housing, which was later rescinded by the school.

Following this, the cats no longer roamed the power plant, but throughout the campus you can still find little wooden shingled cat houses where people are invited to leave food, clearly an initiative continued following Milster’s long history of tending to the Pratt Cats. One sign says, “Thank you for feeding the cats” and encourages people to use the designated food bowls and to discard garbage in the trash. It also offers a facilities email address for anybody with questions or concerns regarding the campus felines (an inquiry we sent went unanswered, however).

“I think about retirement and I’m sort of afraid to make that move…one of the difficulties is that when I leave, a lot of things are going to change,” Milster says. “Is anybody going to give a damn about keeping the engines nice looking? Will any modern manager put up with incandescent lighting here? Who’s going to take care of the cats when I’m gone? I sort of fear for the things which I cherish being threatened.”

The Pratt Institute Steam Engine Power Plant is one of the 150+ locations inside our book Secret Brooklyn.

Next, check out the world-class art all over the Pratt Institute campus.