Before the Whole Foods in Gowanus was built, a handsome building stood alone, left over from the bustling concrete industry that came before. But more than just another pretty Neoclassical building, the Coignet Building was actually a showcase for a new material, known today as concrete, that took the building industry by storm in the 19th century. Moulded concrete, or beton-coignet as it was called in France, was patented by French industrialist François Coignet and consisted of a mix of sand, lime and cement. Beton concrete was showcased to much acclaim at the 1867 Exposition Universelle de Paris.

Though many people were experimenting with similar mixes, Coignet made it possible to mass produce large pieces of concrete and pioneered the use of iron reinforcements. Coignet’s particular mix, perfected through many tests, was found to be particularly durable, adaptable and affordable. The material could be molded instead of painstakingly shaped with chisels and cutting tools. A cement wash could be applied to color the concrete, giving it the appearance of granite, brownstone or whatever was desired.

The Coignet Building, completed in 1873, was once part of a five acre factory along the Gowanus Canal operated by the New York and Long Island Coignet Stone Company. Designed by William Field and Son (which also did the Tower Buildings in Cobble Hill), the building functioned as both an office and a prototype, much like the New York Terra-Cotta Company building that still stands beneath the Queensboro Bridge . The detailing on the exterior referenced numerous architectural styles popular at the time, in order to show the possibilities of the material. The building was landmarked in 2006 by the New York Landmarks Preservation Commission, and the designation report calls it “the earliest known concrete building in New York City.”

On the two facades of the Coignet Building that face a street, there are two Ionic-columned porticos topped by a pediment. Quoining along the edges of the building give it a neo-Renaissance influence. The staircases leads up to rounded doors, a shape that is mirrored on the first floor windows.

On the second floor, both the rounded and rectangular windows are framed by columns and Italianate window-heads. The whole building is topped by a relatively simple entablature. It is believed that the original floors were possibly made of concrete as well.

After its use as the Coignet Stone Company offices, it was used by the Brooklyn Improvement Company, a company owned by Edwin Clark Litchfield, whose grand home, known today as the Litchfield Villa, still stands on a hill on the edge of Prospect Park.

For many years, the Coignet Building was covered in a faux-brick, which concealed the concrete facade. The building was renovated by Whole Foods as part a deal to purchase the land and its completion was long awaited by local residents.

Work by the Coignet Stone Company can still be found today in some of the city’s most famous landmarks – the American Museum of Natural History, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Cleft Ridge Span in Prospect Park and Saint Patrick’s Cathedral.

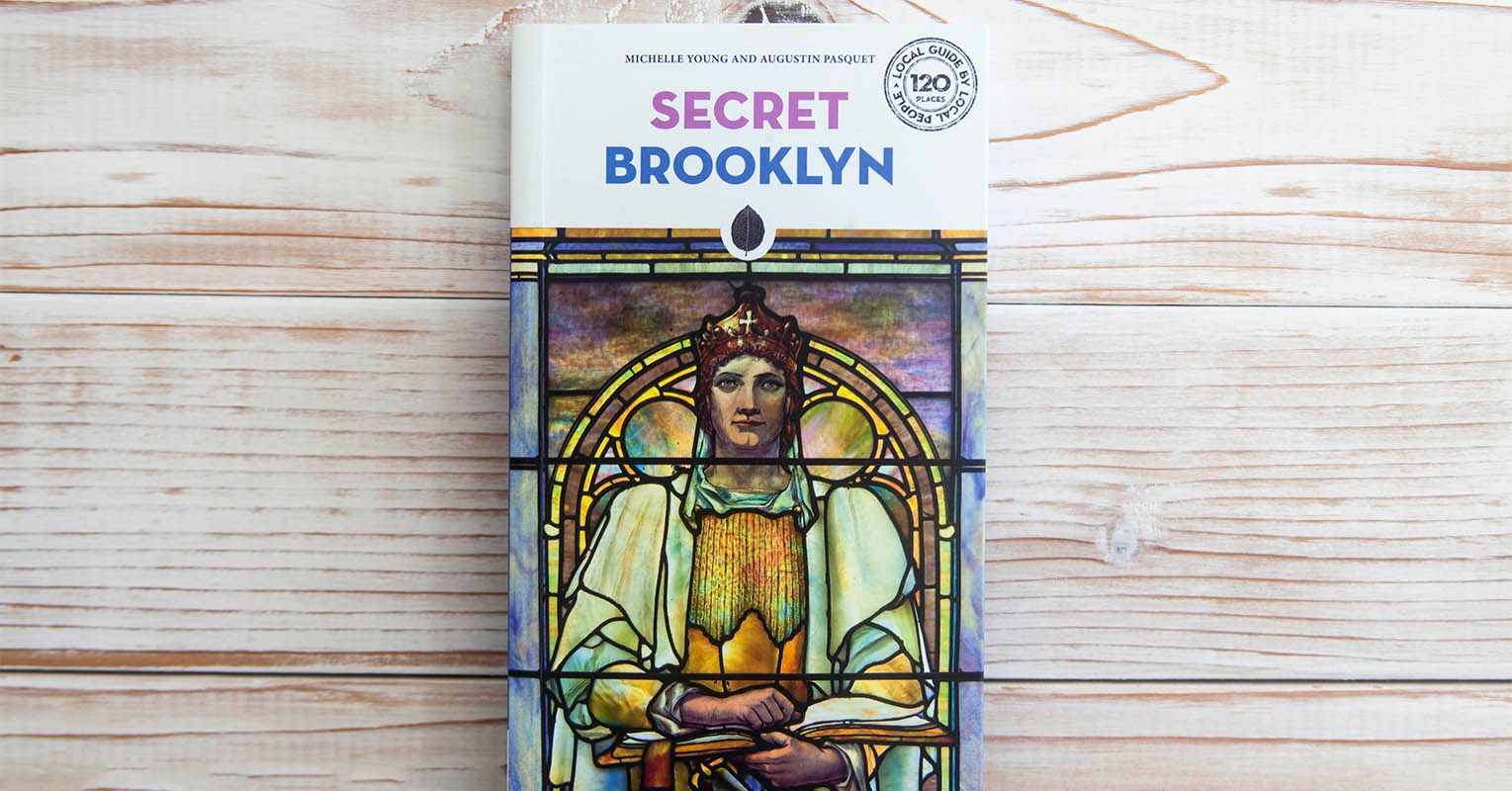

The Coignet Building is one of the 150+ locations from our book Secret Brooklyn. Get an autographed (and dedicated) copy from us!

Next, check out the Secrets of the Gowanus Canal.