Located 30 just miles outside of New York City, in Laurel Hollow, Long Island, less than a mile from the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, the Eugenics Record Office (1910-1939) was a dark episode in New York history. While we almost instinctively associate New York with Ellis Island as the main American port for the arrival of millions of immigrants in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the Eugenics Record Office played a significant role in the post-World War I effort to severely restrict immigration with the passage of the Immigration Act of 1924 (Johnson-Reed Act).

The Eugenics Record Office was one of the main eugenics research and advocacy centers during the global apogee of eugenics in the early twentieth century. The movement was present in thirty-five countries, but it was most popular in Germany, the United States, the United Kingdom, and Scandinavia. Other well-known eugenics institutions included the German Society for Racial Hygiene founded in 1905 and the Eugenics Education Society of London founded in 1907. The role of New York in the eugenics movement was not peripheral; for example, the city’s American Museum of Natural History hosted the Second and Third Eugenics International Congresses in 1912 and 1932 respectively.

The 1924 Immigration Act

The 1924 Johnson-Reed Act restricted immigration alongside “national origin” quotas, aimed at preserving the Anglo-Saxon “stock” of the nation while limiting southern and eastern European immigration. It was no coincidence that calls for restricting immigration came once eastern European immigration surpassed immigration from northern and western Europe, which included a greater number of Jewish immigrants from Poland and Russia. The 1924 Immigration Act did not consider actual percentages of the non-white populations living in the United States at that time as part of the formula for determining national quotas.

The 1924 Immigration Act reduced the national quotas put in place by the Emergency Quota Act of 1921 from 3 percent based on the foreign-born population present in the US in 1910 to 2 percent, and used census figures from 1890 to allocate the national origin quotas. 97.9 percent of quotas were for European nations, of which 88.7 were for northern and western Europeans. These quotas reduced annual immigration from 800,000 in 1920 to 164,667 after 1924.

The quotas were not only racially motivated but in practice absurd. For example, the quota for China was 105 but since the Chinese were already barred from entering the United States and were ineligible for citizenship on the basis of race, the law in practice meant that the quota of 105 was for non-Chinese people of China. Another negative effect of this arbitrary and rigid system of quotas became evident in the late 1930s and the early 1940s as Europeans fleeing Nazi persecution sought refuge in the United States. Furthermore, restrictive quotas rather than ending immigration, created the new problem of illegal immigration.

American Eugenicists:

Charles Davenport

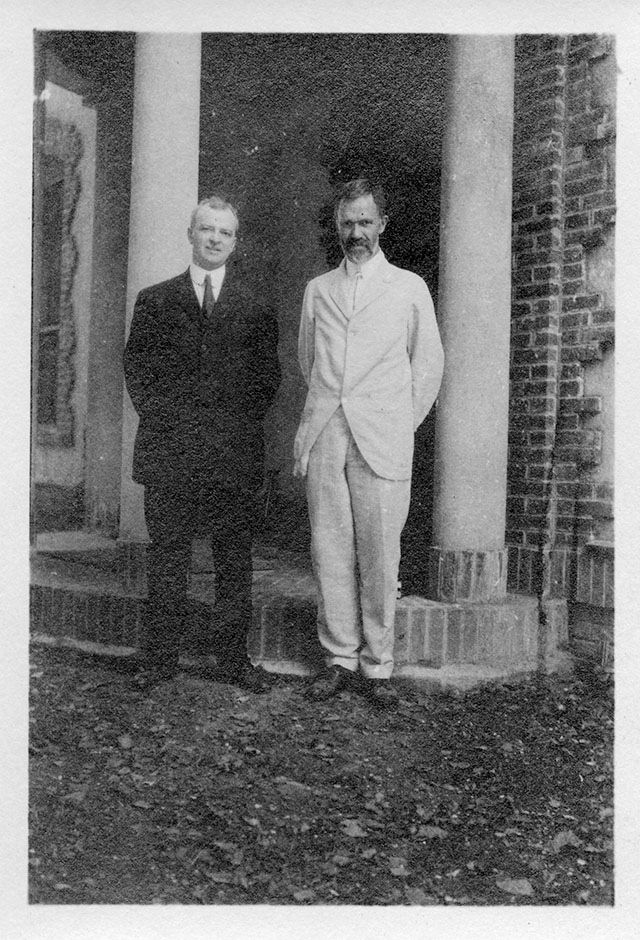

The founder of the Eugenics Record Office was the Harvard-educated zoologist, Charles Davenport (1866-1944). Davenport had grown up in Brooklyn Heights in a family proud of, if not obsessed with, their English colonial ancestry. The elder Davenport, Amzi Benedict had traced the family’s Anglo-Saxon lineage back to the days of William the Conqueror in the eleventh century.

During his studies at the Brooklyn Institute’s laboratory in Cold Spring Harbor, Davenport became a follower of Francis Galton (1822-1911), the English founding father of eugenics. Galton was also known as the father of biometry after his application and invention of statistical tools such as regression and correlation to biological research. Galton, a first cousin of Charles Darwin, believed that societies should promote the reproduction of the talented by encouraging marriages between certain gifted individuals. One of Galton’s main concerns was increasing the fertility of upper-class families. Like any biological determinist, Galton assumed that social characteristics were fixed in race, and opposed reforms to reduce poverty on the grounds that it helped the socially unfit to reproduce.

Davenport was also an opponent of social reform and saw race as immutable. For Davenport, the “melting-pot” was a dangerous concept and rejected racial mixing on biological grounds. In 1902, in his search to test heredity and natural selection in animals with planned breeding experiments and perform quantitative studies on variation, Davenport sought the financial support of the Carnegie Institution of Washington for the establishment of a research laboratory in Cold Spring Harbor, which was denied at first. In 1907, after becoming interested in the role of heredity in personality and mental traits, Davenport’s ultimate goal was to apply Mendelian genetics to race as a way to test Galton’s belief in the superiority of Nordic over Alpine and Mediterranean “races.”

It was finally in 1910 when the Eugenics Record Office was founded with Davenport’s main associate, Harry H. Laughlin as the institution’s superintendent. At an Animal Breeders’ Association, Davenport had convinced Laughlin, who taught agriculture at Kirksville State Normal School (Truman State University), to research humans instead.

The office, built at 1682 Laurel Hollow Road in Laurel Hollow, New York, was a gift from Mrs. Mary Harriman, who helped fund the Carnegie Institute of Washington’s Station for Experimental Evolution at Cold Spring Harbor New York, along with the Rockefeller Foundation and the Carnegie Institution of Washington. Mary Harriman’s father was the president of the Ogdensburg and Lake Champlain Railroad, and her husband E.H. Harriman was brought into the family business (Harriman State Park is one of Mary Harriman’s many philanthropic activities, though her work has been tainted by the strong support she gave to the Station for Experimental Evolution). The office was designed by the firm of Peabody Wilson and Brown, whose work included the renovation of the Hotel Astor, the President’s House at Dartmouth College, and many country estates of the American elite.

The Eugenics Record Office was part of the larger Station for Experimental Evolution that was created at Cold Spring Harbor. Daniel Okrent writes in his book The Guarded Gate: Bigotry, Eugenics, and the Law That Kept Two Generations Italians, and Other European Immigrants Out of America, the trustees of the Carnegie Institution provided $34,250 to get the station started, “the 2019 equivalent slightly more than a million dollars…plus an annual appropriation enabling it ‘to continue indefinitely, or for a long time.'”

Okrent also explains that dynamite had to be used to build the station, as “it was the only way to penetrate the frozen ground before pouring the foundations for the buildings.” The creation of the Station for Experimental Evolution and the Eugenics Record Office vastly shifted the vibe at Cold Spring Harbor, which previously had the feel of a summer camp where student biologists “spent their days rambling through the fields and marshes with nets and pails and Mason jars, gathering specimens for laboratory study.” Now, things would be more “somber in tone.”

Harry H. Laughlin

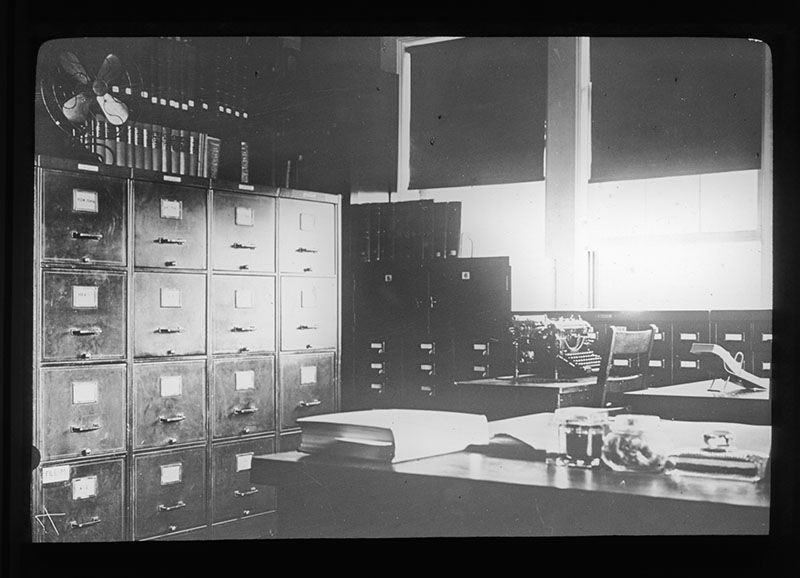

Harry H. Laughlin (1880-1943) believed that social problems were hereditary and sought to remove the “socially inadequate” from society through the promotion of solutions such as segregation, euthanasia, and sterilization. The effects of Laughlin on social policy are undeniable. Due to Laughlin’s political engagement, the Eugenics Record Office was more than a research institution that collected morphological data on social deviants and criminals, cataloged or indexed family traits and advised people on the genetic fitness of their marriages. Laughlin made the Eugenics Record Office, in effect, into a lobbying agency for sterilization and the restriction of immigration. Laughlin lobbied state legislatures to adopt sterilizations of inmates and disabled people, presumably as a means of social reform. By 1938, 30,000 sterilizations had been performed by different states.

Laughlin also inserted himself in the deliberation of immigration policy at the federal level. Congressman Albert Johnson of Washington, Chairman of the Committee on Naturalization and Immigration, impressed by Laughlin’s testimony in 1920, appointed him as an expert witness on eugenics. Laughlin warned the Committee that socially deviant immigrants from southern and eastern Europe were a threat to the racial purity of the nation. In 1923, Laughlin was sent to Europe by the Secretary of Labor to study emigration from its source. It is worth noting how at this time, immigration was an issue under the purview of the Department of Labor. The 1924 Immigration Act, which endured until the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, incorporated the ideas of eugenicists such as Harry Laughlin and Charles Davenport.

In 1936 Laughlin received an honorary degree from the University of Heidelberg for his work on sterilization, which served as a model for the Nazis’ own sterilization laws. As the onset of World War II discredited eugenics, the Eugenics Record Office closed on December 31, 1939.

Nonetheless, the Georgian Colonial-style building still exists today at 1682 Laurel Hollow Road, having been sold off as a private residence. It was last sold for $1.275 million in 2015 (and $999,000 in 2014). While interior images were available on Realtor.com just until a few days ago, archived images on Google show a traditional style home with parquet wooden floors, an angled bannister main staircase, and a country-style kitchen. Some areas were remodeled between the two recent sales, including it appears the kitchen and bathrooms. The home exists down a long driveway so is not visible from the road, just a minute drive away from the main campus of the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory today.

Next, read about a former Nazi neighborhood on Long Island with Adolf Hilter Street. Check out 10 Gold Coast Mansions to Visit on Long Island.