Last Chance to Catch NYC's Holiday Notalgia Train

We met the voices of the NYC subway on our nostalgia ride this weekend!

The Bronx, which had over 100 theaters showing movies and live entertainment in the years before World War II, now has only two multiplexes. Both were built in recent years and are sorely lacking in the architectural character that typified the earlier venues. However, many of those older Bronx movie theaters are not gone, but instead are being reused for other purposes, with varying degrees of preservation of original details.

We’ve rounded up fourteen of these old theaters from across the borough, to look at their history and current condition. These old theaters include a historic landmark that was one of the five celebrated “Wonder Theatres.” There’s a theater whose namesake was arrested for staging an “improper” performance that put a spotlight on sexual exploitation of young women. There’s also a building with mysterious panels on its facade that may provide a hint of its past. Individually and collectively they provide a tangible link to a past filled with fascinating history.

These former Bronx movie theaters have long outlasted vaudeville, silent films, and the era of grand movie palaces. Their survival is a testament to the resiliency and reinvention that is characterizing the Bronx of today. The movies no longer run at these theaters, but they still provide interesting stories. You can continue to explore the forgotten theaters of the Bronx in a virtual talk with Jeff Reuben in our Insiders on-demand archive. The archive contains more than 100 recordings of past live-streamed events. Access to the archives is free for Untapped New York Insiders!

The Loew’s Paradise, located on the Grand Concourse at East 188th Street, is widely considered the grand dame of the Bronx’s former movie theaters. Long before the multiplex era, this single screen auditorium had over 3,800 seats, making it one of the largest in the city. It was one of the five famed “Wonder Theatres” developed by the Loew’s move chain in the late 1920s as movie palaces with highly elaborate details inside and out.

The Loews Paradise was designed by John Eberson, who was the originator and leading architect of this style of “atmospheric theater.” Eberson designed theaters throughout the country and as far away as Australia. Today known as the Paradise Theater, it is now home to World Changers Church. It is designated as both an exterior and interior New York City Landmark.

Opened in 1913, the Spooner Theatre on Southern Boulevard was named for actress Cecil Spooner, who together with her producer/husband, signed a 20-year lease to use it as a base for her theater company. Her association with the site turned out to be short but eventful.

Several months into her residency, Spooner presented a drama called “House of Bondage” which provided a stark look at the practice of forcing young women into prostitution; in those days known as “white slavery.” Shortly before the third performance, she was arrested for presenting an “improper theatrical performance.” (Police had attended the premiere and documented the impropriety with the help of a stenographer.) Spooner was soon released by the authorities but subsequent productions, including a brief run on Broadway, included alterations to the script.

Despite public support for Spooner in response to her arrest, her theater company’s operations ceased in spring 1914 due to financial problems. The venue soon became part of the Loew’s chain and started showing films. Loew’s kept the Spooner name, while Cecil Spooner soon went on to Hollywood for a silent film career.

Spooner Theatre was part of a larger entertainment venue called Hunts Point Palace, which later became famous as a Latin music venue. It is now occupied by stores and while the original theater signage is gone the facade retains ornate gilded details.

Located a block north of Spooner Theatre, the Boulevard Theatre on Southern Boulevard was opened in 1913 by Marcus Loew, the founder of the Loew’s chain which merged with AMC Theatres in 2006. According to a 1913 New York Tribune article, Loew’s Boulevard featured both “vaudeville and moving pictures.”

The 1913 Tribune article noted that the Boulevard Theatre was “tastefully decorated.” This is not surprising considering that it was designed by Thomas Lamb, a celebrated theater architect (more about him later). A sense of that elegance remains; the Boulevard’s facade has been well preserved and undergone restoration in recent years .

The movie theater boom of the early 20th century spread to every corner of The Bronx, but on City Island, with its remote location off of the borough’s northeast coastline and small-town scale, the dynamic played out a bit differently. City Island Theatre, also known as the Scenic Theatre and the Nickelette, was the island’s first purpose-built cinema when it opened in 1910 at the corner of City Island Avenue and Tier Street with a seating capacity of 250. Both its designer, architect Samuel H. Booth, and its owner, Mrs. Miles McDonnel, were local residents. More Mayberry than big city.

By the time the silent movie era was ending in the late 1920s, it was converted to other uses. It served as local headquarters for the presidential campaign of New York governor Al Smith in 1928 and by 1933 it was repurposed as a post office, which remained operating until the 1970s. Since 1977, it has been occupied by the Original Crab Shanty, one of City Island’s many noteworthy seafood restaurants.

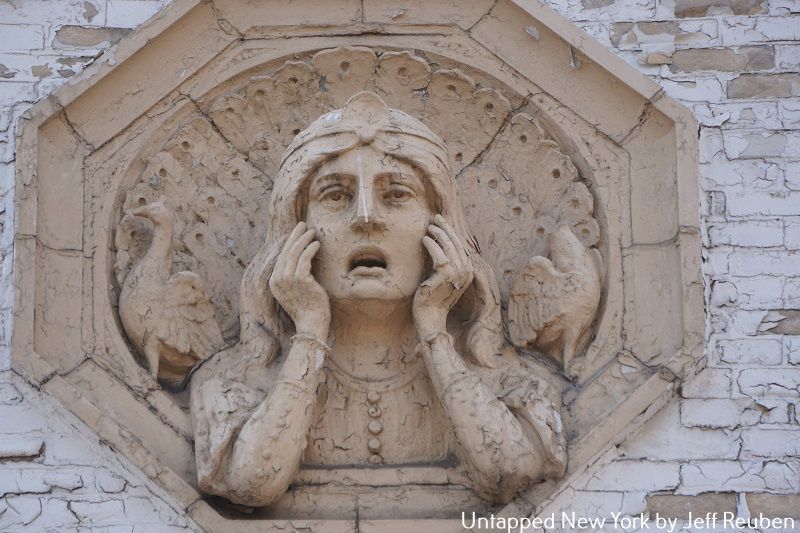

Located down the street from the Cecil Spooner and Boulevard Theatres, the Art Theater opened in 1914. It was a hybrid building, combining a 600-seat theater with stores and an open-air theater with room for about 800 patrons. Its most distinctive architectural feature is its decorative busts on the façade.

It later became Teatro Art, a Spanish language cinema, which in turn was eventually replaced by a Protestant church. Although some of the storefront space is actively used, the church left several years ago and unfortunately the distinctive ornament is in a state of disrepair.

The Art Theater is the work of Swiss-born architect Paul B. LaVelle, who trained at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. LaVelle is notable for later employing and mentoring Hilyard Robinson, the first African-American to earn an architecture degree at Columbia University, who went on to become a leading architect in Washington, DC.

Around the time the old City Island Theatre closed in the 1920s it was replaced by a new movie house, the Raymond Theatre, which operated until 1958. Just a half-block from its predecessor, the new 600-seater was designed by Douglas P. Hall, an architect responsible for several other theaters.

The building reopened in 1960 as the City Island Playhouse, a live event venue, later adopting the name of its forerunner, City Island Theatre. It returned to showing movies in the early 1970s but sometime between then and the 1990s the final curtain came down and it was transformed into a food market, which remains the site’s current use. Yet another old Bronx theater hiding in plain sight.

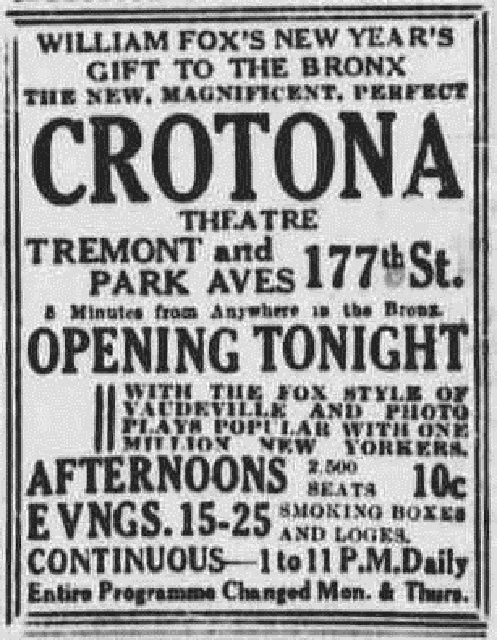

The 2,500-seat Fox Crotona Theatre, located at East Tremont and Park Avenues, opened in 1912 during the silent film era. It was built by film executive William Fox and designed by the aforementioned Thomas Lamb, who also created Fox’s Audubon Theater in Washington Heights and the original Empire Theatre that much later was incorporated into the AMC Empire 25 in Times Square.

Like many silent film era venues, the Fox Crotona featured both an in-house orchestra and an organ. It also hosted vaudeville variety shows and other events such as concerts that were broadcast on radio station WMCA.

According to the Cinema Treasures website (a helpful resource on historic theaters), in later years the Crotona Theatre was operated by the Skouras Theater Corporation and it closed in the late 1950s. Today, the Crotona Theatre lobby on East Tremont Avenue is occupied by an appliance and furniture business.

Built in 1913, the old Bronx Opera House presented opera and plays and later showed movies. Located on East 149th Street, the facade and portions of the original building remain and connect with a new structure built in place of the old theater auditorium.

The revamped site now houses the Opera House Hotel. Perhaps a similar transformation awaits other old venues such as the Art Theater.

The Melrose on East 161st Street was originally a movie theater with a roof garden and was later converted into a ballroom. More recently it has housed a day care center, though it appears to be unoccupied now.

For a 1920s theater, its facade is not unusually elaborate, but it does feature two enigmatic panels. They show two griffin-like creatures grasping a chalice. The date “Mar. 19, 1921” is printed across the bottom. It seems like a cryptic clue out of Dan Brown novel.

What does this mean? There is no definitive explanation available and since Robert Langdon is a fictional character, the best we can offer is an educated guess.

Plans for this theater were first announced in 1916. But construction stalled in 1917 and the site was sold. With the United States’ entry into World War I that year, most construction projects were put on hold. Even after the war ended in November 1918, construction costs remained high. The Melrose Theatre was not completed until 1921.

Given the long delay, perhaps these panels were placed as a way of celebrating the building’s completion. In art and medieval lore griffins were symbols of strength and vigilance. Sticking with the medieval theme, the chalice could be the holy grail. So, in this interpretation, the griffins represents the builders who achieved the holy grail of project completion. A movie theater is a fitting place for a story with such a heroic ending.

While the history of the Paradise is well documented, for some of the other former Bronx theaters, the details of their past are murky. Consider the Concourse Theatre, located one block north of the Paradise at the intersection of two of the Bronx’s major thoroughfares, the Grand Concourse and Fordham Road.

Some current sources state that the Concourse Theatre was built in 1930 as a Loew’s venue and another attributes its design to John Eberson. However, while its exterior features some distinctive architectural details it isn’t typical of Eberson’s signature “atmospheric” style. Also, there appears to be no press coverage from 1930 of a new Loew’s theater at this location.

On the other hand, a 1916 New York Sun article reported on the recently completed Concourse Theatre at this site.

In any event, the much larger, 2,500-seat B.F. Keith’s Fordham Theatre (later part of the RKO chain) which opened next door in 1921 seems to have overshadowed this 600-seat facility. Unlike the Fordham, which no longer exists, the Concourse building continues as well-patronized retail space today and although the original marquee is gone some of its original facade elements remain.

Built in the 1920s at the intersection of Kingsbridge and Fordham Roads, near the Concourse Theatre, the Windsor Theatre came under the control of theater impresario William Brandt in 1930 who renamed it Brandt’s Windsor. In addition to movies, in the early 1930s Brandt presented “tryouts” of new plays to get a little seasoning before heading to Broadway. For example, Mae West appeared in a play there in September 1931, which ran for a week and then opened on the Great White Way.

A 1931 New York Evening Post article noted that “almost any Monday evening after a first performance at the Windsor, the knowing jehus [slang for cab drivers] of Fordham Road line their vehicles up before the stage door, where fares are legion at about 11:15 P.M. The first taxi to leave for Times Square invariably contains as passengers the author, director and producer.”

In the 1940s and early 1950s, Brandt reversed the pattern. The Windsor became part of the “subway circuit,” in which plays were staged at outer borough venues following their Broadway runs. In 1942 the New York Times reported that this business model was a a “gold mine” even though, in Brandt’s words, the “admission prices were ridiculously low.”

Today, the Windsor, located near the Bronx Public Library main branch, is occupied by retail space.

One of the first theaters built in the Bronx, the Metropolis Theatre at East 142nd Street, Third, and Alexander avenues was an aesthetic achievement but a commercial disappointment.

The Metropolis Theatre opened in 1897 as a live performance venue and a book from that year touted it as “handsome and attractive.” It was designed by J.B. McElfatrick & Sons, the nation’s leading theater designers in the years before Thomas Lamb and John Eberson. Besides the main auditorium it included a roof garden and offices.

In booming, turn-of-the-century New York City, the Metropolis Theatre seemed sure to be a success.

However, less than a year after the Metropolis opened it was foreclosed and in the next three decades it went through a succession of operators and alternated between presenting live entertainment and movies. While theaters thrived elsewhere in the Bronx, it struggled and in 1929 Loew’s purchased it for use as a warehouse.

Today only a portion of the original building remains, though it includes the full facade along Third Avenue with some of its original details surviving. A supermarket sits along the 142nd Street side of the site.

Opened by Loew’s in 1928, one year before the larger and more glamorous Paradise, the 3,000-seat Fairmount Theatre had a short stint as Loew’s largest theater in this area of the city. It is is good example of a theater that was developed as part of a larger commercial development. In this case, the building also featured storefronts and office space, with the auditorium located behind the main building. This is similar to the Ed Sullivan Theater (originally Hammerstein’s) built around the same time.

Today a supermarket occupies the ground floor of the building. It is unclear what, if anything, the auditorium is used for.

With its marquee gone and its front facade altered, the Wakefield Theatre doesn’t look much like an old movie house. Today occupied by Greater Faith Temple church and retail businesses, it opened as a cinema in 1927 and operated for over 40 years.

However, behind the one-story entrance on White Plains Road, the large brick theater auditorium is easily seen from the elevated platform of the 233rd Street subway station. Although it now serves a religious rather than commercial role, the church still uses the auditorium for services, including musical performances, as can be seen in this video.

Many old theater facades across New York City have been altered, so in some cases the most reliable way to spot an old venue is to look for the large, windowless brick box set back from the avenue.

You can continue to explore the forgotten theaters of the Bronx in a virtual talk with Jeff Reuben in our Insiders on-demand archive. The archive contains more than 100 recordings of past live-streamed events. Access to the archives is free for Untapped New York Insiders!

Next, check out 10 forgotten theaters of upper Manhattan, unique movie theaters you’ll only find in NYC, and the abandoned Loew’s Canal Theater in NYC.

Subscribe to our newsletter