New York City’s public infrastructure can be taken for granted if the history of the city is not often revisited. Many important infrastructure projects in New York City, such as the Lincoln Tunnel, La Guardia Airport, the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel, Flushing Meadows Park, and the restoration of Bryant Park, are the legacy of the New Deal (1933-1939). During this current moment of crisis for urban living, with a renewed flight to the suburbs, brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic, it is important to look at how many of New York’s most impressive infrastructure projects are the product of an era when the government rose to take a proactive role, as President Franklin D. Roosevelt (1882-1945) did with the New Deal.

Recent gridlocked debates in Washington D.C. over the funding for national infrastructure expansion expose one of the most enduring divides in American history: the rural-urban divide. This divide is not new, as some prefer to believe, but it is rather deep and historically significant. It defines two different forms of social, cultural, and economic organization that date back to the European settlement of North America. The key to Roosevelt’s political success was his capacity to reconcile and address the material needs of both rural and urban Americans.

The Rural-Urban Divide

Since the European settlement of the United States during colonial times, the ideal image of the country was that of an agrarian society of family farms. Agrarianism served to justify the conquest of North America and violent land appropriation from Native Americans, along John Locke’s private property dictum that land belongs to those who can make it productive. Thomas Jefferson also shared this principle and envisioned the United States as a land of self-sufficient farmers or yeomen, in contrast to the Europe of crowded towns and subjugated semi-feudal peasantry. For Jefferson, who associated civilization with cultivation, Native Americans, with their reliance on hunting, posed an obstacle for the westward expansion of the United States. Furthermore, agrarianism carried a moral judgment on cities as sites of material decay and social disorder. However, the pastoral imagine of America was not only made impossible by the expansion of slavery and the rise of large, labor-intensive plantations but by the increasing urbanization of the United States throughout the nineteenth century, in part due to large waves of European immigration. If in 1820, 80% of Americans lived on farms, by 1920 only 30% of the United States population was rural. By the mid-twentieth century, post-war government reorientation beyond urban centers led to the rise of suburbanization, which added a third factor to the rural-urban divide and American politics.

The disdain towards urban America, in particular large cities, later on in the nineteenth century coincided with the settlement of immigrants in these cities. Franklin D. Roosevelt embodied these tensions and contradictions as a country gentleman from rural New York who had a dislike for urban life but worked, nonetheless, to address the social problems of urban America. President Theodore Roosevelt, who had hoped his distant cousin would embrace the Republican Party instead of the Democratic Party, also professed disdain for urban America, its demographics, and politics. Theodore Roosevelt once expressed disapproval about the prevalence of Irish immigrants and their descendants from New York, Albany, and Buffalo in the New York State legislature. In 1910 when FDR first entered New York State politics, as a candidate for the State Senate’s twenty-sixth district, representing the counties of Dutchess, Putnam, and Columbia, he skillfully increased his appeal as a Democrat in a rural district by running independently from New York City’s political machine at Tammany Hall, led then by the Irish-American Charles Murphy. At this point, the challenge for Democrats, mainly in the North, was to overcome the stigma as a party of the urban poor and immigrants.

Franklin D. Roosevelt, as governor of New York from 1929 -1933, sought to incorporate the needs of rural and urban New Yorkers. As a Democratic governor with a Republican-controlled legislature, Roosevelt attempted to fracture the Republican rural base by proactively addressing the difficulties of New York farmers through his Agricultural Advisory Commission. Roosevelt’s commission called for farm relief by proposing a gasoline tax to fund rural infrastructure projects such as roads, schools, and electrification, while centralizing tax collection, eliminating estate taxes to provide tax relief to farmers. Electrification, in particular, was a major rural infrastructure issue, which Roosevelt addressed in part with the St. Lawrence River project. On urban issues, in the wake of the Stock Market crash of 1929, Roosevelt was the first governor to propose state unemployment insurance given the tepid action or wait-and-see approach of President Herbert Hoover. As Roosevelt said in his first inauguration in March 1933, “the nation asks for action, and action now.”

New Deal Infrastructure Projects in New York

The Lincoln Tunnel

One of the major New Deal infrastructure projects of the era was the Lincoln Tunnel which connects Midtown to Weehawken, New Jersey. Completed in 1937, the Lincoln Tunnel, first known as the Midtown Tunnel, was funded by the Roosevelt’s Public Works Administration after the Hoover administration had placed a moratorium on intergovernmental funding for the project in 1931 in reaction to the Depression. In 1933, the PWA loaned the Port Authority $37.5 million for the project. The initial planning in the 1920s for a second tunnel on the Hudson called for two tubes, but only one was opened in 1937. The second tube was opened in 1945 after World War II shortages delayed the project. The third tube opened in 1957.

Construction for the first tube started in the spring of 1934. The area between West 34thand 42ndstreets was razed and an 80ft deep shaft was excavated for subterranean access. The demolition of this part of Hell’s Kitchen, then an Irish immigrant neighborhood, known in prior decades as the turf of the infamous Gopher Gang, created the opportunity for urban renewal of that section of the city. The Lincoln Tunnel opened to traffic on December 22, 1937.

LaGuardia Airport

LaGuardia Airport is also a legacy of the New Deal era. Mayor Fiorello La Guardia, who was an active supporter of the New Deal and had experience in aviation during World War I, sought the opportunity to make New York an air hub. Prior to LaGuardia’s opening on December 2, 1939, New York City’s only commercial airport was the Newark Commercial Airport. Mayor La Guardia initially demonstrated interest in building an airport in Brooklyn’s Floyd Bennett Field, but the opening of the Triborough Bridge and the Queens-Midtown Tunnel redirected the mayor’s attention towards an area more accessible to Manhattan, the marshes on the south shore of Flushing Bay.

The Public Works Administration provided the majority of funds for the construction of the airport with $27 million out of the total $40 million in costs. LaGuardia replaced the private airfield, known then as North Beach Airport, which had been built on the abandoned site of the Steinway family’s Gala Amusement Park. The airport first opened as the New York Municipal Airport – LaGuardia Field. The airport officially became LaGuardia Airport after the Port of New York Authority took control of it in 1947.

The Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel

Although completed in 1950, the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel is another legacy of the New Deal era. This New Deal infrastructure project went through many setbacks. The project was first proposed as a tunnel, but in 1939 Mayor La Guardia decided on a bridge, as it was less expensive to build and operate. Secretary of War Harry Woodring opposed the project because it could obstruct maritime traffic to the Brooklyn Navy Yard. The Reconstruction Finance Corporation provided a loan of $57 million to the New York City Tunnel Authority and Triborough Bridge Authority in charge of the project. Construction started in October 1940, but in 1942, when the United States became actively engaged in World War II, the War Production Board suspended the project until the end of the war in June 1945. The total cost reached $80 million. The Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel is one of the longest vehicular tunnels in North America with a length of 9,117 feet (1.7 miles) and a capacity of 20 million cars per year. The construction of the tunnel’s ramps led to the displacement of the Arab enclave, known as Little Syria, that existed along Washington Street in Downtown Manhattan, just north of the Battery.

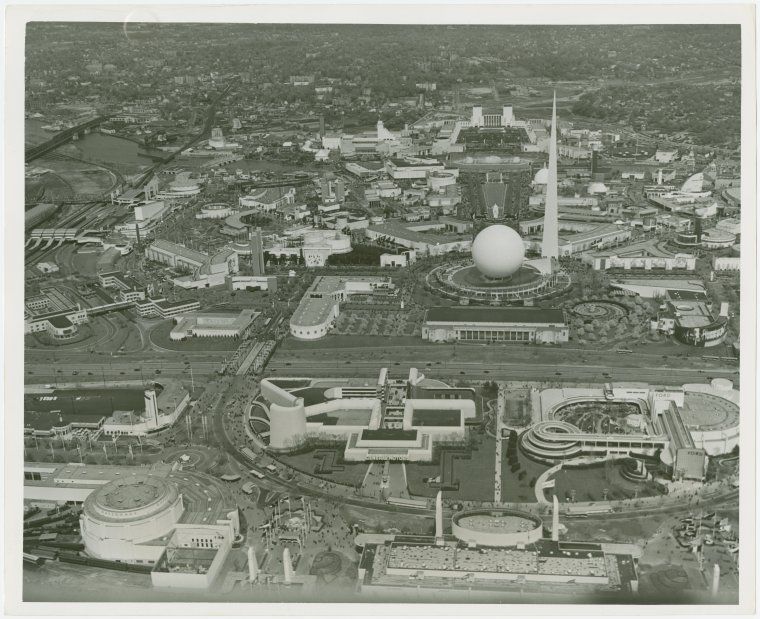

Flushing Meadows-Corona Park

Flushing-Corona Meadows Park is one of the most transformative projects of New Deal New York under the Works Progress Administration. Prior to the construction of the park, these salt marshes, located between the Flushing Bay in the north and Kew Gardens in the south, were a dump for coal ash from industrial furnaces and ash from incinerated trash. For nearly three decades, from 1908 to 1935, the Brooklyn Ash Removal Company used these fields as a dumping ground, leaving ash mounts up to 90 feet high. These ash dumps are famously referred to in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby.

The 1930s plans for the construction of the Cross Island Parkway further highlighted the need to transform the area, which was already a concern for Long Island Railroad commuters from the affluent Gold Coast. In 1935 Robert Moses, then New York Parks commissioner, acquired this area for the city to build a park. That same year, under the initiative of engineer and immigrant from Luxemburg, Joseph Shadgen, the park was selected as the site for the World’s Fair of 1939, under the pretext of commemorating George Washington’s inauguration in New York in 1789. New York at that point had not hosted a World’s Fair since 1853. After two years of non-stop construction, the World’s Fair opened on April 30, 1939.

Bryant Park

The legacy of the New Deal in New York is also visible in Bryant Park. Although the history of Bryant Park goes back to the colonial era when governor Thomas Dongan designated the area as a public space in 1686, the park’s 1934 restoration is a significant part of its history. In its many incarnations, Bryant Park has served as the site of a potter’s field between 1823 and 1840, the Croton Reservoir (1842-1900), a 4-acre lake with fifty feet granite walls, a park, known as Reservoir Square, built in 1847, the Crystal Palace for the World Exhibition of 1853, and the main branch of the New York Public Library which was completed in 1911. After decades of decay, in 1934 architect Lusby Simpson won the redesign contest for the park’s restoration. New York’s Parks Commissioner, Robert Moses made use of the Civil Works Administration (1933-1934) to provide labor for the restoration. The FDR administration implemented the CWA to put people to work as fast as possible in manual labor projects to reduce an unemployment rate of 24.9 percent. The redesigned Bryant Park included additions such as a raised ground that was four feet above the sidewalk level, a larger central lawn, tree-lined pathways, and an oval plaza with a fountain. The redesigned park reopened on September 14, 1934. Since 1974, Bryant Park has New York City scenic landmark status.

The New Deal Legacy

These are just a sample of the most prominent New Deal infrastructure projects in New York City. Other significant infrastructure projects from that era in New York include Queens Boulevard, the Triborough Bridge, Queens-Midtown Tunnel, FDR Drive, and many others. Across the nation, the Works Progress Administration, an agency created to address mass unemployment, for example, put 8.5 million people to work in the construction or improvement of 125,000 public buildings, including 5,900 new schools, 31,000 renovated school buildings, 1,000 libraries, 226 new hospitals, 2,170 renovated hospitals, and 2,700 firehouses. Transportation-related projects included 78,000 bridges, 26 vehicular traffic tunnels, 800 airports, 650,000 miles of roads, and 24,000 miles of sidewalks and paths. The WPA also left a legacy of 8,003 new or improved parks, and 177,000,000 trees planted in public forests. Through the Civilian Conservation Corps, the New Deal also planted 3 billion trees. Besides the WPA, the Public Works Administration, which was the New Deal agency in charge of funding large-scale projects, spent over 6 billion on 34,500 projects, such as the already mentioned LaGuardia Airport and the Lincoln Tunnel, the Hoover Dam, the Overseas Highway that links Miami to Key West, and the Grand Coulee Dam, one of the largest concrete structures in the world.

The New Deal also laid the foundation for what Americans later would define as the American Dream, primarily characterized as homeownership. Prior to the New Deal, the United States was a nation of renters, when only four in ten owned their own homes, however, by the Post-World War II era, the United States became a nation of homeowners.

Next, check out WPA Wall Art on a Wastewater Plant in Queens