After-Hours Tour of "Noguchi's New York" Exhibit

Join an exclusive curator-led tour at NYC's Noguchi Museum!

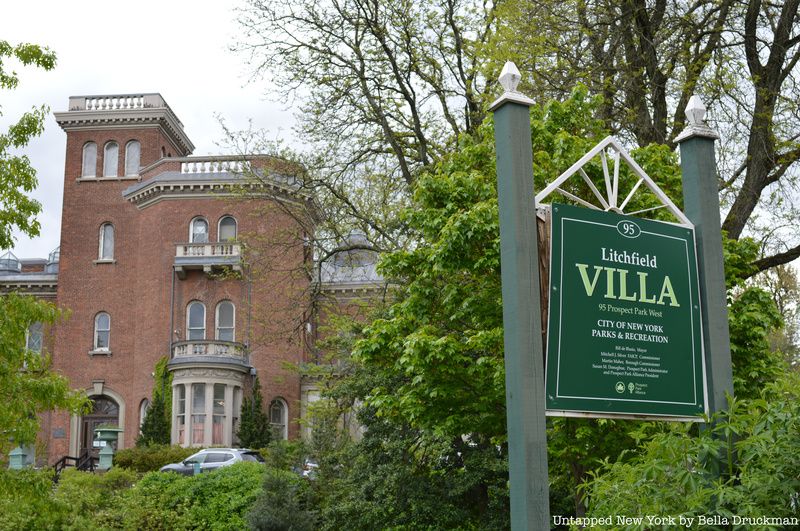

Edwin C. Litchfield, a well-known Brooklynite, revolutionized the Gowanus Canal, turning it from a small creek into a major shipping canal. Despite the rather visible pollution in the Gowanus Canal today, Litchfield left behind a more beautiful landmark in Brooklyn. This landmark, Litchfield Villa, peaks out of the trees in Prospect Park, calling all to see its beauty.

Litchfield commissioned his Italianate-style villa in 1855, costing $150,000. Architect Alexander Jackson Davis would finish the villa in 1857. Gaining fame after building Lyndhurst Mansion in 1838, he would later go on to build New York City’s Federal Hall and the Hudson Valley mansion Locust Grove.

The Litchfield family, including Edwin, his wife Grace, and their five children, lived in this house for years until unforeseen circumstances forced them to move. Litchfield Villa was named a New York City landmark on March 15, 1966. Today, children play catch with their friends and family as cars drive past this historic villa.

Although Litchfield owned much of the land in what is now Prospect Park and Gowanus, Brooklyn, this did not stop the City of Brooklyn from seizing his land. In 1869, the Litchfield family ceded their 50 acres of land devoted to Litchfield Villa. Although the city allowed the family to live in the villa until 1883, Litchfield left the villa for elsewhere abroad following the death of his wife.

Today, the villa, which originally stood amid Litchfield’s hoards of acres, remains in a flurry of trees, bustling New Yorkers, and parked cars. Minutes from the Soldiers and Sailors Memorial Arch, the Prospect Park Zoo, and the Brooklyn Museum, Litchfield remains one of the oldest landmarks in Park Slope.

Edwin C. Litchfield married Grace Hill Hubbard Litchfield on September 14, 1841. Sixteen years after their marriage, Litchfield found other ways to express his love for her, one of which was naming his new villa “Grace Hill” in honor of his bride.

Born in 1818, Grace lived until age 62. Throughout her life, she cared for her five children while her husband worked as a district attorney and oversaw railroad operations. Following her death in 1881, she was buried in Green-Wood Cemetery. Litchfield then left the mansion because without the namesake of his villa, what was the point of staying?

Although the current exterior of Litchfield Villa is exposed brick, this was not always the case. When Davis built the villa, he covered it in a layer of stucco that was later painted to resemble stone. After Litchfield left the home in the early 1880s, the stucco would remain for several decades. Although it is unclear when the stucco was removed, many speculate it was during the 1930s or 1940s.

When the Department of Parks removed the stucco, they planned to but never did apply a new coat to replace the old one that had deteriorate In 1989, the Administrator of Prospect Park said the park had allocated enough money to add the stucco once more. However, they never followed through with the plan.

When Davis built the estate, it expanded over 50 acres. This meant that the property Litchfield owned could contain more than just his extensive villa. Other than the villa, Davis built a coach house, a greenhouse, and a chicken house. During this era, much of Brooklyn consisted of farmland.

These buildings no longer exist, however. Nevertheless, Prospect Park visitors can visit the zoo at the opposite end of the park in lieu of spending time with Litchfield’s chickens. Despite the absence of Davis’ additional structures, other aspects of farm culture still exist at Litchfield Villa.

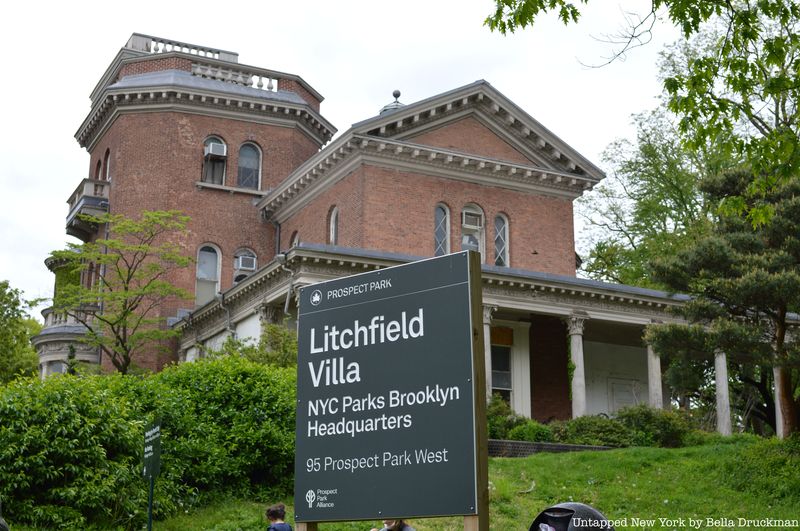

When Davis built Litchfield Villa, he already had extensive architectural practices that he transferred from property to property. One architectural element that he often used were columns covered in corn and wheat. These wooden columns are on the right side of the house and pay homage to two native plants of New York.

Another example of this architectural transfer is the asymmetry in both Lyndhurst Mansion and Litchfield Villa. Although Lyndhurst Mansion offers pointed arches, rib vaults, and flying buttresses dispersed throughout the structure, the villa offers irregularly shaped towers and turrets.

Litchfield Villa has various types of tiles throughout the property. Maw & Company, a well-known tile company, created many of these tiles within the villa. The company has produced tiles in England since the 1850s.

Eugene Patron, the former Press Director of the Prospect Park Alliance, suggested that there had been an overproduction of tiles for the U.S. Capitol. Because some tiles in Litchfield Villa are identical to tiles in the U.S. Capitol, representatives of Maw & Company believe that they are a result of this overproduction.

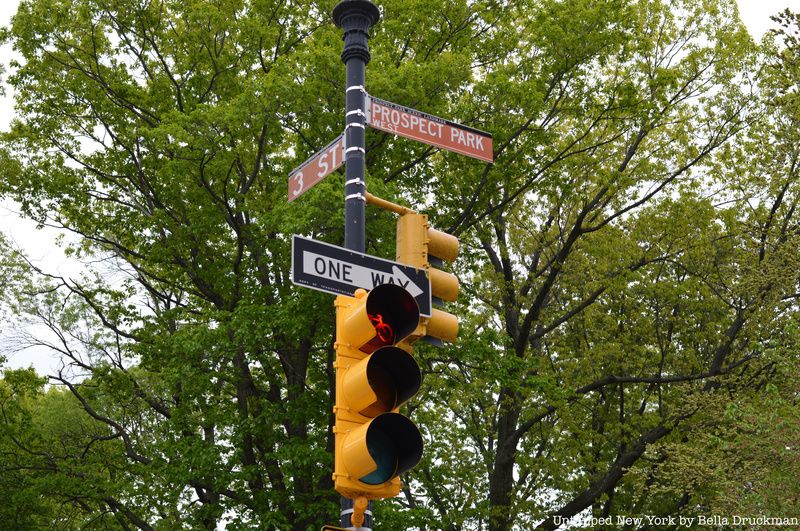

Many wonder why 3rd Street in Brooklyn is twice as wide as the other streets nearby. However, few know that Litchfield used 3rd Street as his driveway and therefore needed it to be twice as large. Litchfield would use the driveway to travel in a carriage from the Brooklyn Improvement Office to his home.

Today, 3rd Street leads to a large opening for Prospect Park. A busy intersection with multiple traffic lights, the 3rd Street and Prospect Park West intersection is now full of cars rather than carriages. Two columns topped with bronze panthers line the entrance.

A rotunda welcomes guests as they enter Litchfield Villa. This is the only aspect of the villa open to the public. A large skylight illuminates the room, bringing sunlight into the otherwise dimly lit room. To the left, a double staircase leads to the Gold Room, the only part of the house with surviving plasterwork. Decorated in the Rococo Style, the Gold Room contains elaborate furniture and decorations. The room once held two Corinthian columns, which were not in fact decorated with wheat and corn.

Conservatories, a drawing room, and a reception room all remain on the ground floor of the mansion, since records show that Grace Hill had a physical impairment. Nevertheless, her family enjoyed the luxury of the Gold Room until they ceded the house to the Parks Service.

Grace and Edwin’s children, whose birth years range from 1842-1849, lived with them in the villa. As a result, they often played with each other on the property. Mary, Frances, Edward, Henry, and Grace would run around the villa, engaging in childish games. Using a ticket window by the home’s dining room, they would play theater.

When their mother died in 1881, only Edwin remained in the home. As a result, when Edwin Litchfield left for Europe and later died in 1885, the logical decision was to pass it off to the parks district. None of the children would extend the Litchfield Villa legacy past their parents.

After Litchfield moved abroad following his wife’s death, he gave his villa to the City Parks Commissioner. Currently, Litchfield Villa is home to the New York City Parks Brooklyn Headquarters.

Although Litchfield Villa is not open for tours, those who would like to visit the mansion can do so for free. Located at Prospect Park West between Fifth and Fourth Streets, the villa is on display for drivers, walkers, and those picnicking in the park. For those who want to see the corn and wheat that adorn the columns of the villa, they can walk up to the villa for a closer look.

Next, check out another home built by Alexander Jackson Davis, Lyndhurst Mansion!

Subscribe to our newsletter