In the mid and late-19th century, photographers captured scenes of New York City life on some of the earliest cameras invented. The advent of the daguerrotype reached the city in the late 1830s, which produced a unique image on a polished, silver-plated copper sheet. Samuel Morse, the inventor of the telegraph, moved to a studio at the corner of Nassau and Beekman Streets, where he instructed aspiring photographers and image-makers. By 1844, there were 16 daguerreotype galleries in New York City, and by the 1850s, early photographers roamed the streets of New York to find the perfect shot. And there has also been controversy over the first photograph of New York City: while the New York Times reported that the first known photograph likely dated back to 1848 of the Upper West Side, a daguerrotype by Morse of the Unitarian Church on the east side of Broadway across Waverly Place dates back even earlier, likely to fall 1839 or winter 1840.

However, most of these burgeoning photographers were men, and the work of many unsung female photographers of the 19th century is on the whole lost. Some work, though, still survives by Matilda Moore, a photographer of Civil War era New Yorkers. Below, we’re pleased to presente an excerpt from the book Women in the Dark: Female Photographers in the US, 1850-1900 by Katherine Manthorne, a Professor of Art History at the Graduate Center, City University of New York. The author will be a guest on our upcoming book event about female photographers in 19th century NYC, free for Untapped New York Insiders. Get your first month free of membership with code JOINUS.

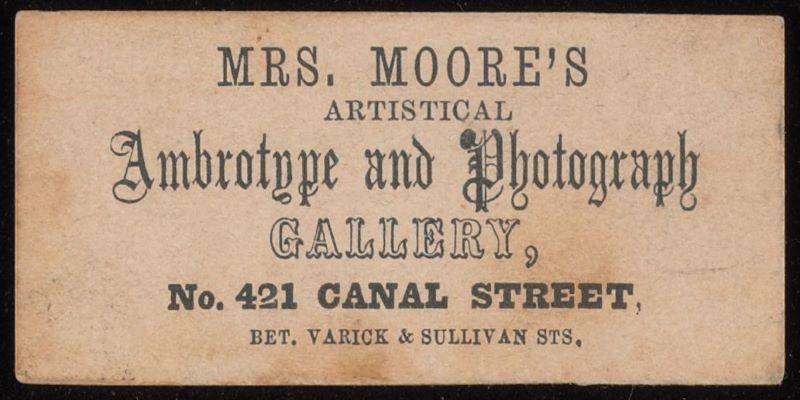

“Mrs. Moore,” as she signed her work, contributed to New York City’s nineteenth century’s visual culture and demonstrated women’s distinctive contribution to the field of photography. She ran a successful studio in the city for over two decades at the same location at 421 Canal Street, between Varick and Sullivan Streets. Matilda Moore (b.c. 1832) was active from about 1860 to 1883 but we know little else about her career except that it coincided with the craze for the carte de visite or cdv, an inexpensive photographic print affixed to a card measuring 2 ½ x 4 inches.

With painters something remains of their long-forgotten artistic reputations, but the body of work they produced has often scattered. Moore, by contrast, is known primarily through 100 or so surviving cdv’s (compared to 200,000 by leading male contemporary Abraham Bogardus) that we can identify as hers by the logo she stamped on their versos. These small sepia-toned portraits are like the crumbs dropped by Hansel and Gretel and help us recover her legacy. The insignia on her card changed from a cartouche to an eagle surrounded by a garland, but the inscription remained constant:“Mrs. Moore, 421 Canal Street, New York.” This commercial branding of female identity shatters the stereotype of the middle-class female sheltered from the world of commerce. These otherwise conventional women were setting up their establishments side-by-side with men, whether it was in a nascent western town or — as in Moore’s case — on one of the most heavily trafficked streets of one of the busiest cities in the world, making it as photographers.

By the 1850s the term “self-support” came into use to earmark a stratus of “respectable” women who — whether they were widows, orphans, spinsters or divorcees — had to seek employment. In the early 1800s women had few options for reputable paid work, usually in domestic service or the clothing trade. By 1869 Harper’s Bazaar – edited by Mary Louise Booth — ran a double-spread illustration “Women and Their Work in the Metropolis” that presented an expanded panorama of female employment. Front and center is the proverbial seamstress – overworked and underpaid – surrounded by vignettes of her colleagues setting type, binding books, making corsets and umbrellas, and mounting photographs. This last-mentioned activity acknowledges women’s entrance into the field that had been expanding rapidly since the “invention” of photography in 1839. The timing was significant, offering fresh opportunities just as the old ones were being taken away by Irish, German, and other trans-Atlantic men seeking refuge in American cities.

Little wonder then that women opted for this new, burgeoning technology where they could get in on the ground floor. There was no a priori hierarchy or division of labor, no hallowed guilds or schools that excluded them. They were as free as men to order how-to manuals, study the work of leading figures like Mathew Brady. and experiment on their own. Like their male counterparts, they had to learn by trial and error how to operate cameras, develop and print the pictures, and market their establishments. Some were technically minded, others were more steeped in the artistry of it, and many had a practical knack for business. Mrs. Moore seemed to have been blessed with all three.

In an era when women rarely owned businesses, photographic studios were an exception. In Illinois Candace Reed initially worked with her husband and after his death she took over the business. In California Mrs. Cardoza divorced her husband and turned to photography to support herself and her children. City directories typically listed women only if they were heads of households; otherwise only the husband’s name appeared, with no mention of his spouse. Trow’s New York City Directory for 1865 recorded “Moore, Matilda, wid[ow] Michael,” but that is the sole reference to a husband. The U.S. Census for 1860 contains a few more tantalizing bits of information about Moore. She identified herself as a 28-year-old female and the proprietor of an Ambrotype Gallery whose birthplace was Prussia. She possessed no real estate, but indicated a personal estate of $1,000. More revealing still, she identified as a member of her household Joanna Gulliver, a black 17-year-old female born in New York. There was no occupation listed for Gulliver but she must have combined the duties of a live-in domestic servant with those of photographic assistant in exchange for room and board.

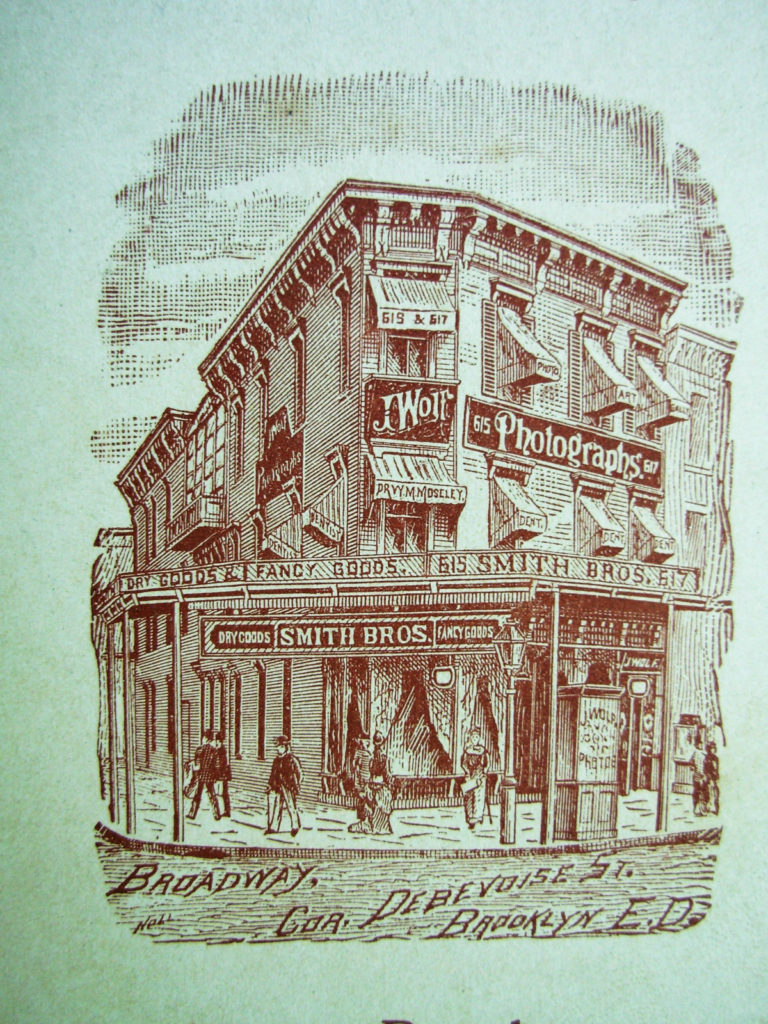

In 1861 Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper showcased the new studio of famed photographer Mathew Brady with its elegant gallery hung with his most eye-catching and expensive “Imperial” portraits. Moore likely visited it and studied his style of portraiture, the bread and butter of the urban studio photographer. It was around this time that she set up her establishment, although it would hardly have approached the impressiveness of Brady’s. But timing is everything, and soon Brady like many photographers would turn their lens on the Civil War that erupted in April 1861. War is good for photography, as families who procrastinated having photos taken suddenly needed them for keepsakes to present to the son or brother or husband going off to war. And once those men acquired their uniforms, they stood proudly before someone’s camera to have wartime separation pictures taken for wives, mothers and sweethearts.

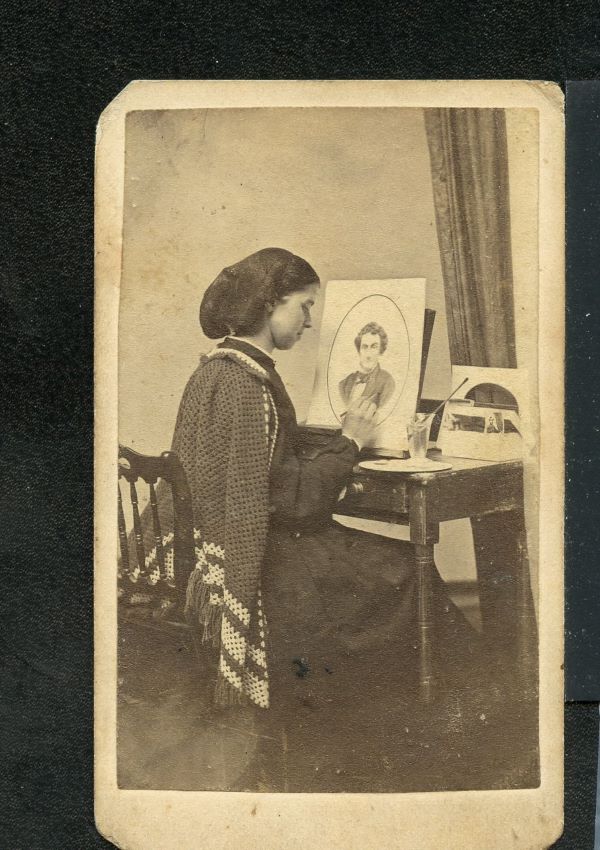

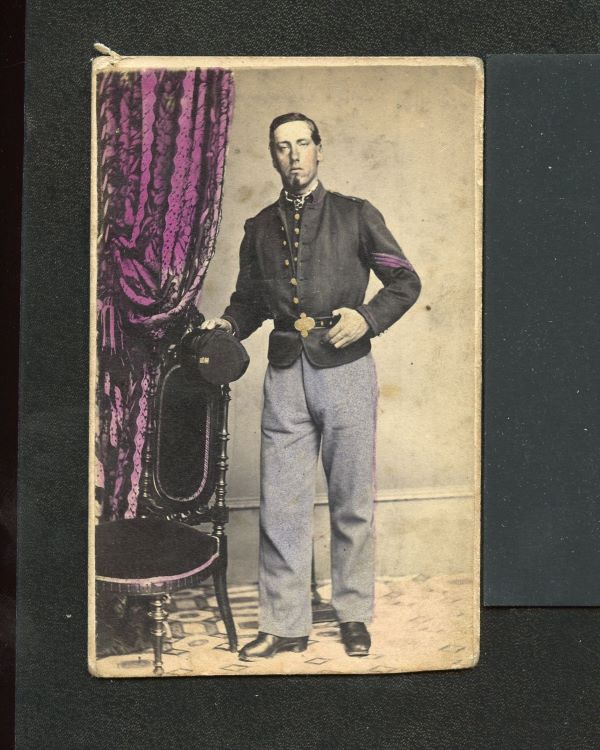

One unidentified member a New York regiment found his way to Moore’s studio and looked directly at her directly at her as she pulled the lens cap off the camera, counted the seconds, and replaced it. In that interval was she thinking of a son or a husband gone off to war? With her carte de visite camera she created eight shots, in four different poses; they show him in full uniform, consisting of light pants, belt with metal buckle, and dark-toned jacket. Standing in full length, he holds his hat in right hand, which rests on upholstered, armless chair. The identical chair, patterned floor covering and drape appear in others of her cdv’s including a young girl with a muff. In Moore’s work the figure stands out against the background and appears natural among the studio props compared to sitters in most run of the mill cdv’s. She effectively posed her clients to present the image of respectability. Sometimes sitters wanted a touch of color, as in the case of the soldier, likely done by a young woman she employed as a retoucher/colorist or perhaps by her own hand.

In 1883 a notice appeared in The Photographic Times and American Photographer offering for sale Moore’s “good payable photograph gallery; situated on one of the best localities in New York” as well as her 4 x 4 camera fitted with Morrison’s copying lens; two backgrounds, and other accessories. The following year leading male photographer Abraham Bogardus ran a similar advertisement. The photographic business was changing rapidly, as the Eastman Dry Plate Co. made prepared plates readily available commercially. As the new era dawned, the older photographic pioneers stepped aside. Sadly, that’s the last we hear of Matilda Moore. But it was the discovery of her cdv’s in antique malls and on-line marketplaces that inspired me to search for her and other women who worked for decades producing technically skilled and historically important photographs, and ultimately to write this book. So the legacy of Matilda Moore and the other “Women in the Dark” endures.

Join our upcoming book event about female photographers in 19th century NYC with Katherine Manhorne, free for Untapped New York Insiders. Get your first month free of membership with code JOINUS.