Staten Island has a skeleton in the closet. One of the most horrifying pieces of history in New York City can be found near the very center of the Staten Island Greenbelt. It was here that one of the most notorious institutions in the world was located: Willowbrook State School.

In 1947, the complex, which built and managed by the State of New York, opened with the intent of serving those with developmental handicaps but the dark reality of the conditions in the facility were kept out of sight from the public. Enter Jane Kurtin, the first journalist to try and pull the veil off of Willowbrook in a print exposé for the Staten Island Advance. She was accompanied by then-unknown reporter Geraldo Rivera who took a WABC camera crew into Willowbrook at the invitation of a whistleblower, Dr. Michael Wilkins, who provided Rivera with a stolen key and helped him hop the fence. Wilkins was desperate to expose the plight within the institution that former U.S. Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy once called “a snake pit.”

It was Rivera’s report that forced the public to finally turn its eyes towards Willowbrook and the American mental health system more broadly. It was the first time a large audience saw the sights and sounds of Willowbrook. According to the original report:

“There was one attendant for perhaps 50 severely and profoundly retarded children. Lying on the floor naked and smeared with their own feces they were making a pitiful sound, a kind of mournful wail that it’s impossible for me to forget. This is what it looked like, this is what it sounded like, but how can I tell you about the way it smelled?; it smelled of filth, it smelled of disease and it smelled of death.”

Geraldo Rivera, from Willowbrook: The Last Great Disgrace, circa 1972

With many an exposé, articles, civil suits, and even more disturbing instances of abuse and neglect, Willowbrook State School was shuttered on September 17, 1987.

Despite the institution’s closure, the legacy of Willowbrook lives on, partly serving as the inspiration for the second season of American Horror Story, Asylum. Yet, perhaps what happened on the site of Willowbrook immediately post-closure is just as disturbing as what happened while it was in operation.

From 1972 until 1987, several children on Staten Island disappeared, having thought to have been kidnapped and murdered by a vicious killer only known by the ominous name “Cropsey.” Andre Rand, a former Willowbrook ward attendant from 1966 to 1968, was found guilty of kidnapping five separate children, with the body of 12-year-old Jennifer Schweiger found in Willowbrook Park adjacent to the former campus and Rand’s homeless encampment.

Rand, along with a collection of former Willowbrook patients, were thought to have lived in the remaining abandoned infrastructure of the campus, as well as in the New York City Farm Colony. It was theorized that within the Farm Colony, cult-like sacrificial rituals were performed by the infamous Process Church of the Final Judgement, the same organization that serial murderer David Berkowitz (the Son of Sam) was thought to have been in cahoots with during his murder spree.

During the investigation into Jennifer Schweiger’s disappearance, Rand’s history of misconduct with children resurfaced. He is thought to have not only killed Jennifer but also abducted four other children over the course of fifteen years. Rand’s status as Cropsey is still debated by some, given that there was no physical evidence linking Rand to the crimes. Regardless, he was sentenced to 25 years to life in 1988, with the now 77-year-old serving time at The Great Meadow Correctional Facility in Washington County, N.Y., 70-miles north of Albany.

Roy Kersey, who has personal connection to Willowbrook tells Untapped New York, “My mother worked as a teletype operator there during WWII when it was Halloran Hospital and met my father, who was an Army accountant, there. Later my mother returned to Building 32, where she was a steno/typist for the doctors. That building was for higher functioning women and I don’t think my mother saw much of the horror. I was a psych intern there in 1969 for three months in the summer. I did some psych testing, mostly of infants, and some research at the NYC public library, but I did get a ‘tour’ of Building 19 and was disgusted by what went on but at 21 years old, in that time period, I didn’t know what to do…it was accepted by those around me. I did meet at least one child who seemed to have been wrongly placed there. He spoke well and used his time making little sculptures out of aluminum foil!… I remember exploring the Main Building there in 1969 and going up to the upper floors, which were deserted even then, strewn with broken hospital beds.”

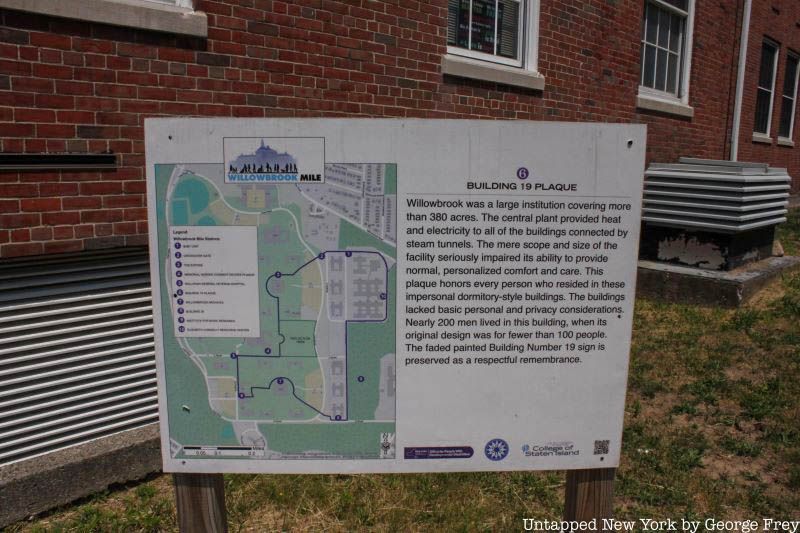

Nearly 34 years after the closure of Willowbrook State School, the former campus is now home to the College of Staten Island, operated by the City University of New York (CUNY), which opened its doors on the site in 1993. In 2016, the College of Staten Island, thanks to the efforts of The Staten Island Developmental Disabilities Council, opened the Willowbrook Mile, a trail that winds throughout the campus and has plaques denoting where the wards of the institution once stood and the buildings from the Willowbrook campus that are still standing.

The Memorial Garden:

Here, a plaque commemorates the 1975 decision to close Willowbrook and reintegrate its residents into the community. The judgment required services to be available in the community for former patients, leading to normalized and non-segregated care for those with special needs. From that point on, the ways in which we care for the disabled in this country has radically changed, thanks to the efforts of many at Willowbrook. This site is in honor of those who fought for the civil rights of the disabled, a fitting spot to start or end your walking tour.

Building 29:

This still-standing structure was one of the many buildings at Willowbrook that housed individuals whose families lived on Staten Island. Although some of the patients were disowned or abandoned, many were brought here by their families, who were told that their loved ones would be given the treatment they needed. The children, though, often were unable to speak for themselves, and parents were not allowed inside much of the facilities apart from the official room where they would visit their children.

It wasn’t until reports by Kurtin and Rivera that these parents became aware of just what was happening inside the rest of the institution. One such patient was Judy Moiseff, who is afflicted with cerebral palsy and lived in Willowbrook for nearly a decade. She now runs the company Judy Speaks, which specializes in disability awareness and sensitivity training. You can watch her testimony here, where she describes her emotional trauma from her experiences living in the institution.

Rivera’s Exposé Site:

Made infamous by Geraldo Rivera’s 1972 report, this site, which is now home to the on-campus Barnes & Noble bookstore, was where cameras first captured life in the facility. Many aids to the patients were overworked and underpaid, since financial problems led the facility to be understaffed. Because of this lack of aids, many were unable to care for all of the patients, leaving many vulnerable. Dr. Michael Wilkins, featured in Rivera’s 1972 WABC program, was one such member of staff who was fired by the administration due to his efforts to organize a demand by parents for better conditions.

Willowbrook Archives:

The library at the College of Staten Island houses the Willowbrook Archives in which the conditions of patients were recorded and preserved. The archives also include historical documents related to the site’s construction, as well as artifacts that detail the experiences of guardians and staff members. The library is closed currently due to COVID-19, but information about the archives can be found here.

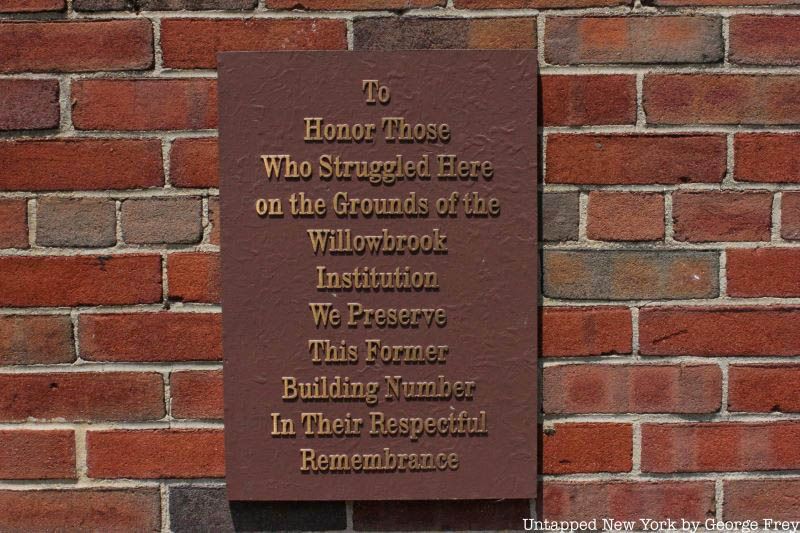

Building 19:

Here, at the southwestern most corner of the College of Staten Island’s campus, stands a faded sign that once denoted the location of Building Number 19, a men’s dormitory known for its zoo-like conditions. Ward 19 was designed with 100 people in mind, but it would go on to house twice as many. Today, the site is home to the university’s department of Biological and Chemical Sciences. The former sign for building 19 stands as a reminder of the inhumane living conditions that the patients experienced. In one photograph, 50 metal beds were placed head to toe along one sidewall of a large room, leaving a small walkthrough with another set of metal beds to the left. The room was surrounded by large institutional windows with no curtains, the walls bare and the room devoid of color.

The Baby Unit:

The Baby Unit was where infants and young children were housed. Like Ward 29, the building is on the eastern side of the campus and is mainly fenced off. The unit was reported to have overcrowding, which resulted in a lack of care to the institution’s most vulnerable patients. Children were often left for long periods of time in standing boxes, which allowed people to straighten and control their posture. Physical therapists in the unit were employed on a consultation basis, with direct hands on treatment implemented by aides.

Crossover Gate:

This small road connecting A Street to Loop Road was the main thoroughfare in and out of the eastern portion of Willowbrook State School. As stated in the CSI guide for the Willowbrook Mile: “This gate symbolizes the crossover from institutionalization and isolation to integration into society for people with disabilities. Through this crossover, the property began to transition from acreage that once stifled growth to one that offered an enriched life with hope and opportunities.”

The IBR:

The IBR, which stands for The Institute for Basic Research in Developmental Disabilities, was among the first largescale institutes in the world with a specific mandate to conduct basic and clinical research into the causes, treatment, and prevention of developmental disabilities. The IBR was also the site of one of the most disturbing incidents to ever have occurred at the institution. Known as the Willowbrook Hepatitis Study, children were purposely given hepatitis via food and drink, and doctors observed just how the sickness affected them. These violations on the rights of patients led to major reform movements across the country, leading to informed consent that protects the human rights of research subjects.

Halloran Hospital:

The Halloran General Veternan Hospital was originally built for housing wounded veterans during the Second World War, and was the largest Army hospital in the U.S. at the time. The hospital closed in 1951 and was incorporated into the Willowbrook Institution.

Connelly Resource Center:

A plaque commemorates Elizabeth A. Connelly, an assemblywoman who advocated for the rights of patients and disabled New Yorkers as a whole. She passed in 2006, and an annual conference on developmental disabilities and autism has been held in her honor. According to the CSI guide, “it discusses the need for sustained advocacy and constant vigilance to ensure that people with disabilities continue to receive the opportunities needed to lead lives of value and worth.”

Next, check out 10 Abandoned Hospitals and Asylums Around NYC!