After-Hours Tour of "Noguchi's New York" Exhibit

Join an exclusive curator-led tour at NYC's Noguchi Museum!

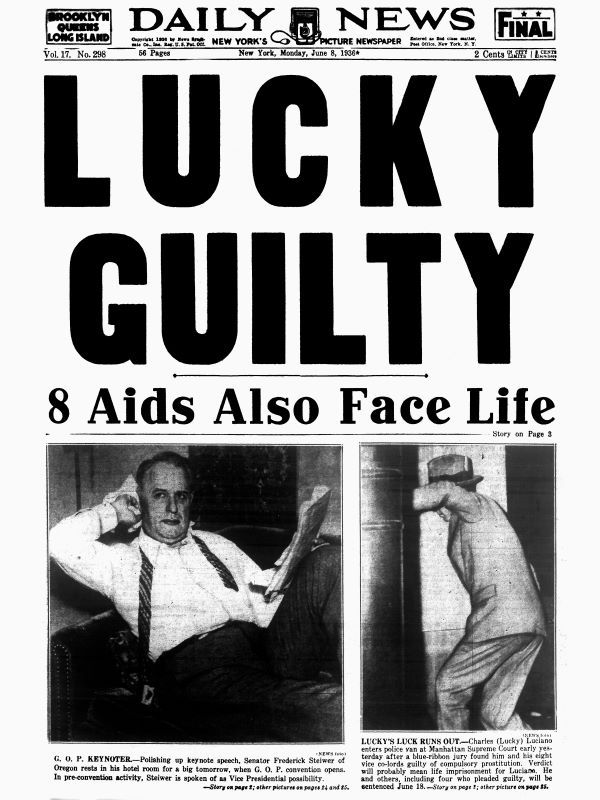

This month marks the 85th anniversary of what was billed at the time by the New York newspapers as the “Trial of the Century” – the trial that convicted notorious mobster Lucky Luciano and eight of his associates. But it was a relatively unknown and unlikely figure who clinched the case against Luciano and the mob: Eunice Hunton Carter, the first Black woman to work in the New York prosecutor’s office and the only woman and person of color on Dewey’s investigative team.

The wily Luciano remains infamous as a symbol of mob brutality and brilliance – it was he who first came up with the idea of improving the mob’s “efficiency” by reorganizing it to mimic a successful corporation. His conviction propelled his nemesis – special prosecutor Thomas E. Dewey – to fame: Dewey went on to become a three-term New York governor, and, very nearly, President of the United States.

Eunice Hunton Carter Carter made the link between the mob and prostitution, countering the prevailing assumption that the mob was not involved in prostitution. Ultimately, it was the prostitutes whose testimony sent Luciano and the others to prison.

Carter inherited from her family a strong work ethic, bravery and a dedication to social justice. Her grandfather was a slave who purchased his own freedom and became a successful businessman in Chatham, Ontario, a small enclave in Canada that became a refuge for former slaves. Carter’s father, William, was one of the first top Black administrators of the international YMCA, tasked with the job of integrating the YMCAs in the South during the stifling era of Jim Crow.

Her mother, Addie, was a key organizer in the Black Women’s Club movement, a reform movement dedicated to providing educational and social services to the poor. She also became part of a team of three women who traveled to France during World War I to provide assistance to Black soldiers. Below is an excerpt from Eunice Hunton Carter: A Lifelong Fight for Social Justice by Marilyn Greenwald and Yun Li that offers a glimpse into the sensational trial that captivated New Yorkers in the summer of 1936.

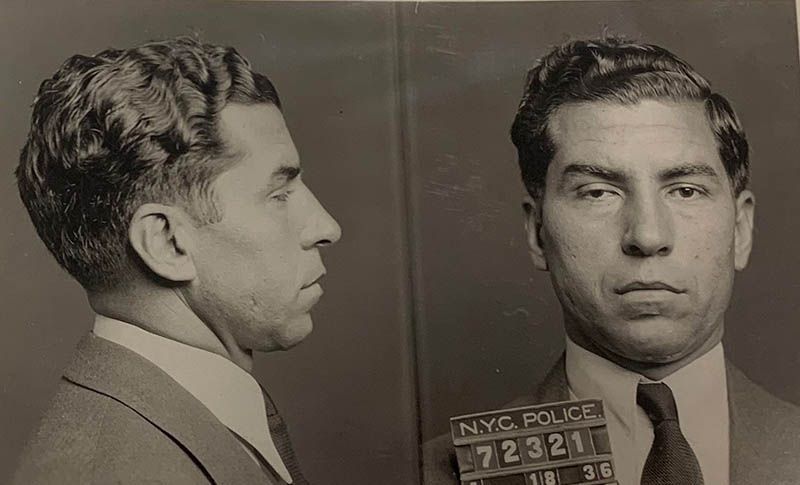

The long-awaited trial of Charles “Lucky” Luciano began on May 11, 1936, and the court setting looked like an armed camp. A heavy police guard surrounded the defendants as they emerged from a prison van and made their way through a crowd of several hundred spectators in front of the court building. Each of the ten defendants had an armed guard as they entered the courtroom and sat in chairs that lined the side of the room.

Outside, detectives and uniformed cops formed a human barricade that extended into the street. Luciano, dark and heavy-jowled, wore a blue suit, white shirt, and black tie. He appeared in good spirits, chatting and laughing with his fellow prisoners as the trial got underway. Prospective jurors, batteries of lawyers, and the defendants and guards jammed the courtroom, leaving no room for visitors.

At 10 am, in the New York Supreme Court in Manhattan, Thomas E. Dewey officially started the proceedings against Luciano and nine other men on trial for compulsory prostitution. They were held on an aggregate bail of $1.175 million, Luciano’s being the highest at $350,000. ($1 million in 1936 would be worth about $18.6 million in 2020). All had past records of indictments, but this time they were indicted by an extraordinary grand jury, which filed a sixty-page document accusing the ten defendants on ninety counts. If convicted on every count, they would face a maximum sentence of 1,950 years.

News of the trial filled the front pages of New York newspapers before it began, the stories hyping it and claiming it was a “departure” in America’s fight on crime—it would mark the first time an underworld vice lord was charged with the crime of which he was actually suspected. Previously, wily and well-known mobsters like Al Capone and Waxey Gordon had been convicted only of the crime of tax evasion.

Before the trial, all 110 witnesses had been kept in jail—for their own protection and to make sure they would not flee. Eighty of the witnesses were women, fifty-five of them residents, and 20 operators of houses of prostitution, which were known as “disorderly houses.” Dewey’s team carefully selected the ninety proposed cases in an attempt to prove that Luciano maintained complete control over the vice syndicate. Based on Eunice’s work at the magistrates’ court, she made sure all the prostitutes who were material witnesses had an immediate connection to Luciano’s ring. They were all tried in the magistrates’ court and represented by the mob boss’s attorney Max Rachlin or someone in his office—usually bail bondsman Jesse Jacobs and attorney Abe Karp. None of them had any prior jail time. Eunice had also set forth the old records from magistrates’ court in detail from docket book entries and court files, to serve as the immediate foundation of evidence in the trial.

In the courtroom, all eyes were on Eunice, who, being sworn in, said:

I’m a Deputy Assistant District Attorney of the County of New York, associated with Thomas E. Dewey, Deputy Assistant District Attorney of said County. Charles H. Farrell, Esq., Clerk of the Women’s Day Courts, located at 425 Sixth Avenue, Borough of Manhattan, County of New York, is in the possession, in his official capacity, of certain papers and records more particularly described in the order hereunto annexed. Said papers and records are necessary and material evidence in the People’s case in the Criminal Action now pending in the Extraordinary Special and Trial Term of the Supreme Court of the State of New York, held in and for the County of New York, entitled The People of the State of New York v. Charles Luciano, etc., et al., defendants.

The papers and records she referred to related to the arrests of people charged with acts of prostitution, she said, and were “a part of the criminal enterprise conducted by the defendants in said criminal action.” Eunice continued that this was the first time such evidence had been introduced in a vice trial: “I have been orally advised by Charles H. Farrell Esq. that neither he nor the court of which he is clerk will be seriously inconvenienced by the production of said papers and records at the trials of said criminal action above referred to. No previous application has been made for this or any similar order to any court or judge.”

Eunice not only played a crucial role in laying the groundwork for the trial but as the solo woman on Dewey’s team, she was also instrumental in extracting evidence from the prostitutes. It wasn’t smooth sailing for the investigators on Dewey’s team to question the prostitutes jailed at the New York House of Detention in Greenwich Village before the trial. Most of them approached the women with a tough and threatening attitude, while some wouldn’t come close to them without wearing gloves. The prostitutes were so intimidated that they wouldn’t speak up or only told lies at first.

It was not until Eunice decided to talk to them in a warm and soft manner that the team was able to obtain their stories one at a time. Eunice knew it was essential to gain their trust and make sure they were treated well in prison, so she bought clothes for them and let them see family members if possible. Many of the prostitutes who worked indirectly for the vice syndicate were also drug addicts, and most were poor; Dewey’s team knew they could not be under the influence of drugs when they testified, so some were undergoing withdrawal. Eunice realized it was necessary to treat those vulnerable with extra care and sensitivity.

Over the weeks of detention, those prostitutes have gone through a change in attitude and manner, a matron at the jail told New York World Telegraph. “They were generally hard and tough when they came in and most have changed. Some were college girls and quite a number were high school graduates. Contact with the young lawyers and investigators who questioned them brought back something of their home culture. They spoke better, acted better, and forgot the manners of the places they had been in, for the time being at least,” the matron said.

To Dewey, getting a conviction against top members of the mob’s governing council, known as the Commission, began with the process of jury selection. He believed it was vital to put together a panel consisting of middle- and upper-class New Yorkers whom he thought were inherently offended by prostitution and suspicious of immigrant defendants. And, as it turned out, he didn’t have too much trouble getting what he wanted. He managed to handpick jurors who were mostly bankers, executives, and businessmen. The trial impaneled a so‑called “blue ribbon” jury, where the prerequisite for serving was previous jury service—at the time, it was mostly those who were self-employed or employed in managerial positions who had the flexibility to serve. The jury pool was weighted heavily with professional men. The jury selection would be made from a pool of two hundred, “made up of bankers, brokers, business executives and a sprinkling of clerks, teamsters and tradesmen,” the New York Daily News claimed. As the writers of a lengthy New Yorker profile of Dewey wrote, members of blue-ribbon juries usually felt naturally predisposed to believe that they were part of the prosecution and that they have been “divinely appointed to convict.”

When it was time to winnow down the pool of candidates, only the most elite made the cut. Dewey had his eye on the president of Goldman Sachs, only to be informed that the company was about to launch a new bond issue, and the man had planned a trip around the country in May and June to arrange it. “Any interruption of his plans will, no doubt, cause considerable irritation,” Dewey’s assistant wrote in a memo to the team. The team, headed by the detail-oriented and perfectionist Dewey, wanted to leave nothing to chance. Ultimately, the final jury with alternates was composed of fourteen successful White business people with prior jury experience, all of whom had read about the case in the newspapers.

Dewey spared no expense with these blue-ribbon jurors, and he made sure they had luxurious accommodations at a five-star hotel. He booked them large rooms at the Grosvenor Hotel and instructed hotel personnel to give them an unlimited supply of free breakfast food each day. Dewey made sure that jurors ate without charge at the hotel restaurant, and they were not expected to pay gratuities of any kind while at the hotel. On the days when the court was in session, lunch would be provided at a restaurant near the courthouse. In contrast, the women who testified were paid about $3 a day, earning a total of $150 to $200 for their participation. But Dewey’s team did treat them in the weeks before the trial to perks such as shopping trips and movies.

Get the book Eunice Hunton Carter: A Lifelong Fight for Social Justice today!

Next, check out 10 Famous Mob Hangouts of NYC!

Subscribe to our newsletter