New Book Reveals the Frick Collection's Luxurious Interiors

See the stunningly restored rooms of a former Gilded Age tycoon's mansion, now home to one of NYC's most illustrious art museums!

It can be argued that the Pan American Exposition of 1901 was one of the defining moments of arts and culture in Buffalo. This legendary event brought immense recognition to the Queen City at the dawn of the 20th century. The architecture and artwork associated with the exposition reflected the optimism of Buffalo — and the nation — during the period and set it apart from its Paris and Chicago predecessors. Likewise, it punctuated the efforts of many in the Queen City to ensure the place of art alongside industrial growth and evolution. According to plan, the end of the exposition meant the demolition of all the structures associated with it, save one which has since served as one of the anchors of the city’s cultural campus. Nearby, another contemporary structure failed to open in time for the World’s Fair of 1901 but would soon after carry on the artistic legacy envisioned by Lars Sellstedt and others. Thus, it is perhaps fitting that the regeneration of this second structure coincides with the exposition’s 120th anniversary.

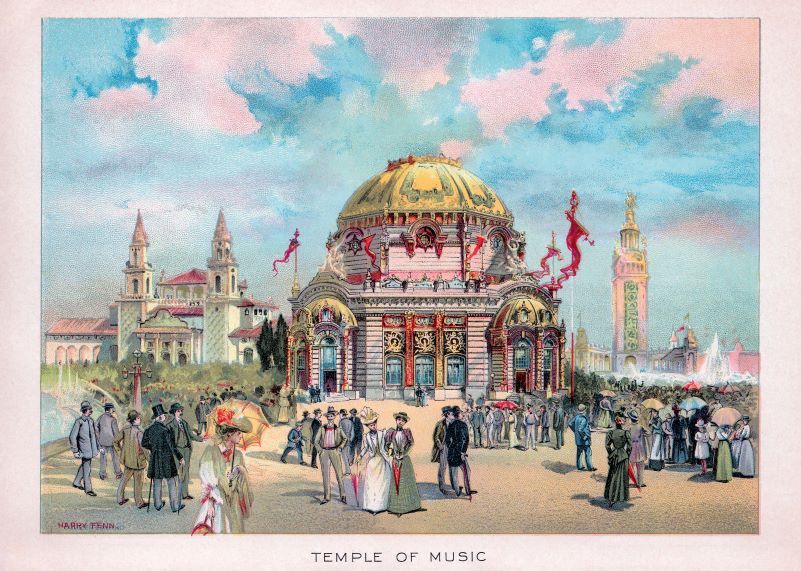

Unfortunately, most people know of the Pan American Exposition for another reason, one that many feel had affected the city’s future for decades to come. This was, of course, the assassination of President William McKinley. Today, the Temple of Music is gone, and a small stone marker in the median of Fordham Drive is all that remains to mark the crime scene of September 14, 1901. There is nothing like the murder of a nation’s leader to really get your World’s Fair on.

Despite the President’s death, however, the Pan American Exposition brought a whole new level of recognition and respect to the incredibly talented community of artists in Buffalo (and the United States) on an international scale. In fact, the entire nation was brought into the spotlight thanks to the incredible efforts of the fair’s Art Committee and The Buffalo Fine Arts Academy. The structures and exhibits created in 1901 were the largest and most important of their time. They laid a foundation for American artists and sparked a legacy that continues to thrive today.

To execute their vision, the exposition’s board of directors created a subcommittee of eight of the nation’s most notable architects to be led by John M. Carrère. This Board of Architects was charged with creating “a plan which shall be beautiful to the eye and which shall afford entertainment for the visitors.”

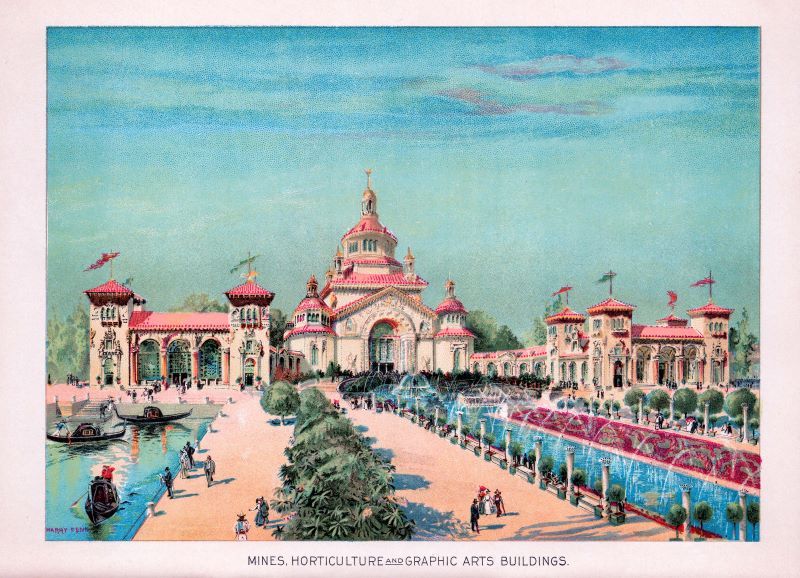

Another priority was to distinguish the Buffalo exposition from the architecture of the World’s Columbian Exposition held in Chicago in 1893. Thus, the architectural style drew from elements of Spanish and Latin American design, mixed with influences from Italy and elsewhere in a style dubbed “Free Renaissance.” Bright colors would play a central role in this scheme — whereas Chicago had shown the world “The White City,” Buffalo’s exposition would be a “Rainbow City.”

Assisting Carrère were two other notable figures: a Director of Sculpture and a Director of Color. To fill the latter position, the chief architect chose Charles Yardley Turner. The recipient of numerous artistic awards, Turner had developed a significant reputation as a mural painter. In his youth he began his artistic career studying drawing at night while working for a Baltimore architect. He would later study in New York and Paris. In 1883, he was awarded the Hallgarten prize for The Courtship of Miles Standish, a series of works based on the Henry Wadsworth Longfellow poem. A decade later, he served as the assistant to Francis David Millet, the director of decoration for the World’s Columbian Exposition.

Turner’s color plan treated the entire exposition as a gigantic palette. The unique and ambitious scheme gave every physical aspect of the Pan Am an all-encompassing story of its own. “It was for us to make the color of the exposition tell something, the same story as the sculpture,” Turner explained. “Accordingly, we have used bright, brilliant hues on the buildings that are suggestive of the early life of man.”

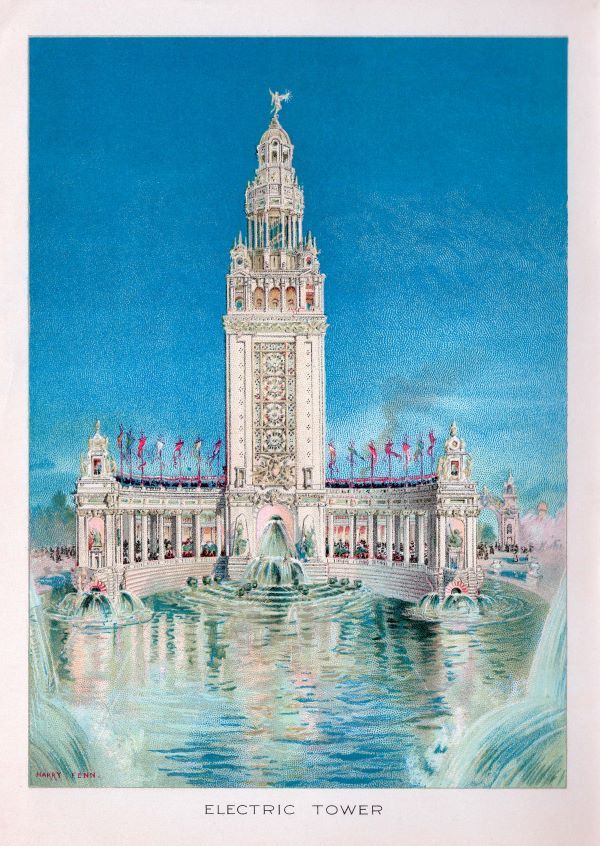

But the symbolism expressed through color did not stop there. As a visitor entered and then progressed through the exposition grounds, the colors selected for the structures implied a story of inevitable evolution. Early buildings, such as the Horticulture and Government buildings, wore a bright palette of “primitive or primary colors.” But Turner noted that as one moved further into the grounds, “the decorations become more sober.” The evolutionary tale told in color culminated with the Electric Tower, which Charles described as “a harmony of green and gold on an ivory ground.”

Furthermore, nearby Niagara Falls provided a unifying tint to the whole of the exposition. “The lovely green of Niagara water, rich as the green on the peacock’s wing, appears in its purity on the electric tower, to be echoed in every structure of the show-city. Not a building is there which is without its notes of Niagara-green.” As it happened, most visitors to the exposition did not enter the grounds through the southern entrance, as imagined in Turner’s color plan; they instead traveled to the fair by means of trolleys or trains, and thus either entered through the northern gate or through those on Elmwood and Delaware Avenues.

Elements of Turner’s color plan are exhibited in a promotional booklet, entitled Pan American Exposition Buffalo, 1901. In addition to text and black-and-white illustrations, the booklet features a series of 12 beautifully colored lithographs by noted artist Harry Fenn. Born near London in 1837, Fenn went on to become known for his landscape art, as well as his illustrations for such publications as Century Magazine and Harper’s Weekly.

It should be noted that Miss Adelaide Thorpe, the Assistant Director of Interior Decoration (the first of its kind at a World’s Fair) added her own creative process to the architectural color palette laid down by the Director of Color, which would “relate as far as possible to the exhibits contained therein.” Miss Thorpe was Turner’s assistant for seven years prior to the Pan Am, and though most men doubted her ability to carry out such work, her remarkable experience as an artist and a businesswoman quickly changed their tune. By May 8, 1901, Adelaide had 150 men working under her supervision to decorate the buildings in order to finish by Dedication Day on May 20.

In addition to the unprecedented color plan for the structures, the fine arts exhibits at the Pan Am Exposition provided a showcase for local artists, as well as those from around the country and the world, on a scale that eclipsed previous world’s fairs. The Pan Am’s Art Committee gathered works from more than 650 exhibitors in the United States alone. Almost 1,600 pieces (mostly paintings) were displayed at the Fine Arts exhibit. It took an entire month to situate them properly. Many legends such as Henry O. Tanner, Maxfield Parrish, Albert Bierstadt, Maurice Prendergast and a personal favorite , Winslow Homer , participated. For the exhibit, Homer submitted 21 original watercolors from his travels to Bermuda and The Bahamas. Today, they are considered some of his finest works.

Of the many Buffalo artists who participated, one female artist of note was Evelyn Rumsey Cary, who painted the iconic Spirit of Niagara for the exposition, reproductions of which remain popular throughout Western New York. Cary was, in fact, one of many female artists exhibiting their works at the fair. She was joined by talents like Mary Cassatt, Cecelia Beaux and several other incredible sculptors. At the 20th century’s onset, this kind of presence at a major international exposition was undoubtedly a significant achievement for women artists.

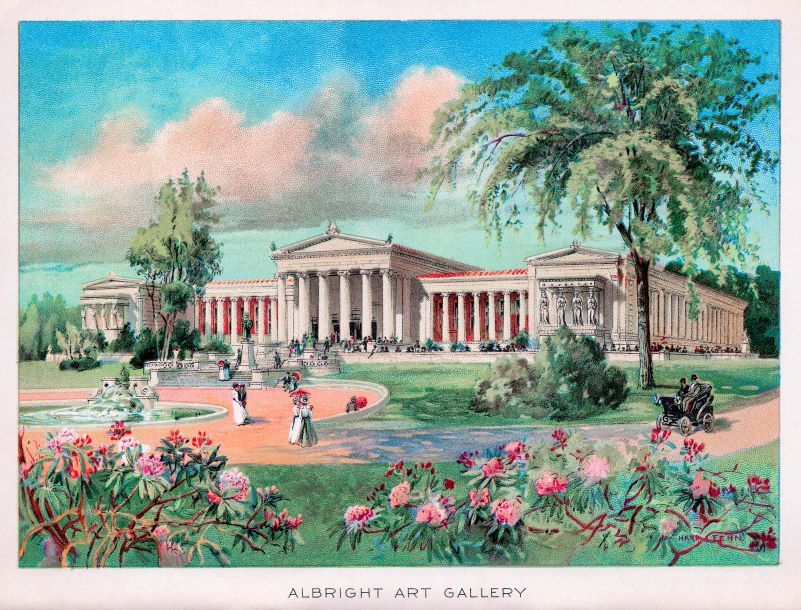

How fantastic would it be to be able to step back in time and see this momentous exhibition of art? It is unfortunate, indeed, that the Art Committee did not see photography as a worthy medium alongside traditional paintings. A gallery of photography in 1901 at an exposition of this magnitude would have been a very bold, progressive undertaking. But what a spectacle it would have been. It wasn’t until the “International Exhibition of Pictorial Photography” was held at the Albright in 1910 that an attempt was made to elevate it to an artform.

In its entirety, the fine arts exhibit, matched in scope by C.Y. Turner’s color scheme and A.J. Thorpe’s interior decorating, showed the world that American artists had just as much technique, talent and skill as those of the Old World in Europe and beyond. Those in charge of this curation were very confident they had achieved such a goal. Reginald Cleveland Coxe, president of the Buffalo Society of Artists, wrote:

We have been in a condition of pupilage till now, gathering in all the knowledge we could from every strong master of school. This exhibition will start a new era, where we will and can walk alone.

Fast forward to the year 2021, which marks the 120th anniversary of the spectacle. The final moments of the Pan American Exposition of 1901 have long passed, and the grounds are sadly, with one exception, demolished. Of all the incredible architecture that stood on the site, only one permanent building remains: the New York State Building, prominently situated in Delaware Park. Other scattered fragments of the fair also survive, though. Designed by Buffalo architect George Cary (brother-in-law to Evelyn Rumsey Cary), the New York State Building was planned from the beginning to outlive the exposition. In 1902, it became home to the Buffalo Historical Society, now The Buffalo History Museum.

A second contemporary structure stands not far from this sole Pan Am survivor, though it would not receive its first official visitor until after the exposition had ended. In January 1900, the board of the Buffalo Fine Arts Academy met to consider the question of how to present the arts at the coming World’s Fair. At that time, John Albright announced his intention of donating funds to establish a permanent gallery for the academy. The resulting E.B. Green-designed Albright Art Gallery was to be the home for the fine arts exhibit at the Pan American Exposition, but delays in obtaining sufficient quantities of the high-quality marble specified for the project delayed completion until May 1905, a full four years after the opening of the Pan Am. As a result, the art exhibited during the exposition was housed in a temporary brick and steel building, also funded by John Albright and designed by Green, and was situated near the modern location of the McMillan tennis courts.

As the 120th anniversary of Buffalo’s World’s Fair is observed, perhaps it is only appropriate that the gallery, soon to be known as the Albright-Knox-Gundlach Art Museum, is once again feverishly moving towards completion. As in 1901, this epic renovation promises to ensure the prominence of art in Buffalo, maintaining the vision of the academy a century ago, albeit in an evolved form. But in the 21st century, Buffalo’s first permanent gallery is joined by numerous other organizations, dedicated to the promotion of the area’s artistic talent, past and present. Across the street, within sight of the former Pan Am grounds, stands the Burchfield Penney Art Center. Just a short ride down Delaware Avenue (by trolley in 1901, by car in 2021), the repurposed Delaware Asbury Methodist church today is home to Hallwalls and Babeville, each continuing their own version of an artistic vision for the city and the region. And the Buffalo Society of Artists, formed just a decade before the Pan Am, also continues to thrive in its mission to support local artistic endeavors, as do others too numerous to mention here.

In 1901, Buffalo’s Pan American Exposition was a reflection of the perceived importance of American art as well as an embodiment of the optimism of a city at the turn of a new century. Mary Brown Hartt wrote in the Buffalo Courier of 1901;

Incomparably the finest legacy of the experience will be an awakened civic consciousness. The rush and vigor of a thoroughly lively town are going to leave behind them a divine discontent with the old order of things. And that means civic regeneration.

Colorful, beautiful and awe-inspiring; Henry Fenn’s lithographs show us a grand exposition to be remembered for all time — proof that our immense wealth was not limited to grain and steel, but also included a rich American culture and exceptional artistic value. It could be said that the regional renaissance of recent years, as well as the sustained appreciation for the arts, are fitting tributes to the vision of the civic — and artistic — leadership of over a century ago.

Next, check out 15 must visit places in Buffalo!

Subscribe to our newsletter