♀️ The Trailblazing Women of Wall Street

Women have long shaped Wall Street—even when history tried to write them out.

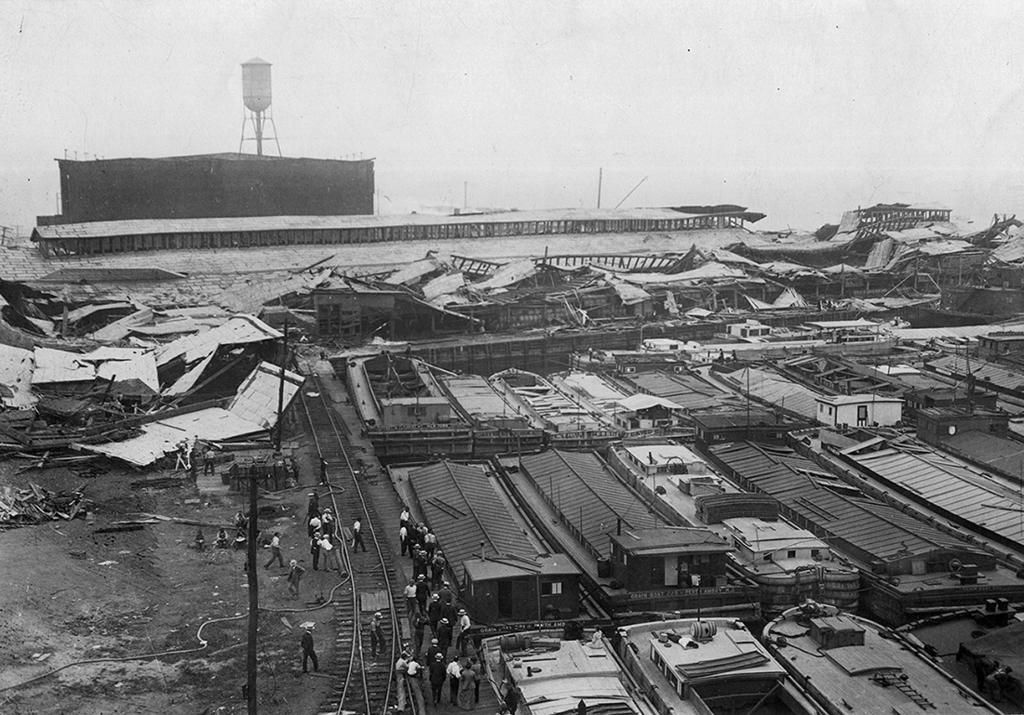

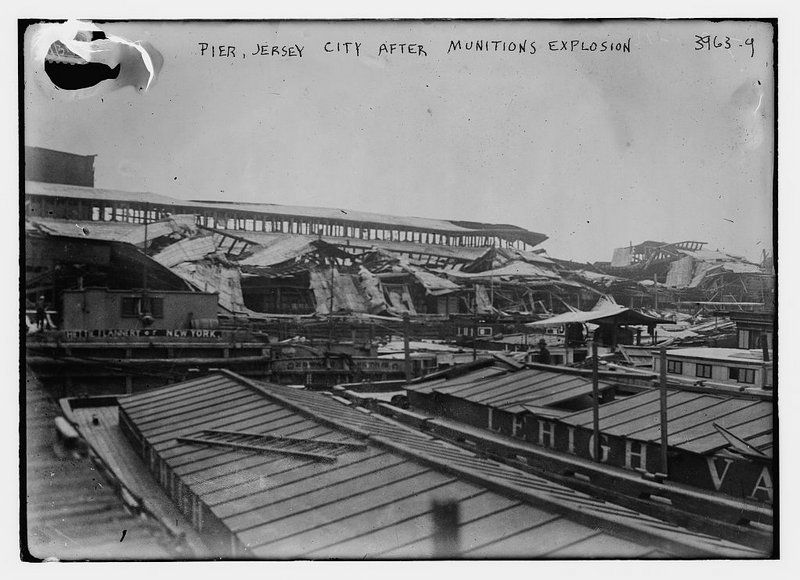

On July 30, 1916, a dark Sunday morning in Manhattan, people were woken up by a deafening explosion in New York Harbor. At 2:08 a.m., the first and largest of the explosions took place, and a second occurred at 2:40 a.m. The explosion, at the Black Tom railroad yard, had the equivalent strength of a magnitude 5.0 to 5.5 earthquake on the Richter scale, and its effects reached as far as Philadelphia and Maryland.

Two million tons of war materials packed into train cars had exploded at the Black Tom railroad yard, corresponding to Liberty State Park today. The explosion shattered windows in lower Manhattan, Times Square and Jersey City, and three men and a baby were killed in the event. The stained glass windows at St. Patrick’s Cathedral were no more. Shrapnel even disfigured the Statue of Liberty, whose torch has been closed to the public since 1916.

Black Tom Island was artificial and was created by landfill around a rock of the same name. The island was considered an environmental hazard, especially following an accidental January 26, 1875 explosion that killed four. By 1880, the island was transformed into a 25-acre promontory and was finally connected with the mainland to use as a shipping depot. A mile-long pier on Black Tom Island contained a depot and warehouses for the National Dock and Storage Company.

But what could have caused this explosion? Many at the time did not know that Black Tom Island was used as a major munitions depot. But following a German blockade by the Royal Navy during World War I, American munitions could only be purchased by the Allied powers. And Germany was not happy about that whatsoever. As it turns out, German agents wanted to prevent American munitions ships from supplying the Royal Navy, even though the U.S. was officially neutral at this point.

To destroy the U.S.-made munitions, German agents in an act of sabotage attacked the island. One of the first major explosions took place around the Johnson Barge No. 17, which contained 50 tons of TNT and 417 instances of detonating fuses. Germany’s decision to stop the sale of munitions resulted in $20 million in damages (about $476 million today), with damage to the Statue of Liberty alone coming in at $100,000 at the time.

But the police could not immediately determine the culprits. Police at first questioned two watchmen who lit fires to keep away mosquitoes, but they were soon after removed from the list of suspects. The Secret Service investigated some German attacks, while The Bureau of Investigation — the FBI’s predecessor — tried to find the culprit as well but to no avail. The New York Police Department’s Bomb Squad perhaps had the most qualified anti-sabotage investigators, but the German agents who blew up Black Tom were not identified at the time. Perhaps it was Michael Kristoff, a Slovak immigrant and U.S. Army veteran who admitted to working with German agents. Or maybe it was German saboteurs Kurt Jahnke and his assistant Lothar Witzke (they are still deemed legally responsible). Some investigators even pointed fingers at the Irish republican organization Clan na Gael.

Although authorities could not figure out the culprits at first, the incident led many Americans to take a more critical and sour stance toward Germany. The U.S. declared war on Germany officially a year later after the discovery of the Zimmermann Telegram, in which Germany made a secret offer to Mexico to ally against the U.S. After Germany continued unrestricted submarine warfare on ships crossing the Atlantic, the U.S. had enough and entered the war.

The Lehigh Valley Railroad Company operating the Terminal was sued by the Russian government for having relaxed security that made an attack like this quite easy. At the same time, the company sought damages against Germany, and it took over 20 years for a commission to declare that Germany needed to pay $50 million in reparations. In 1953, the Federal Republic of Germany settled on $95 million, and the final payment was issued in 1979.

Following the incident and other similar ones, Congress passed the Espionage Act, which intended to prevent the support of American enemies during wartime. NY Police Commissioner Arthur Woods stated, “We must not again be caught napping with no adequate national intelligence organization.” Efforts to increase the strength and capacity of the Bureau of Investigation seemed to work since German schemes in the US would soon after stop. A plaque at the site today notes, “You are walking on a site which saw one of the worse acts of terrorism in American history.”

Next, check out The Top 10 Secrets of Liberty State Park!

Subscribe to our newsletter