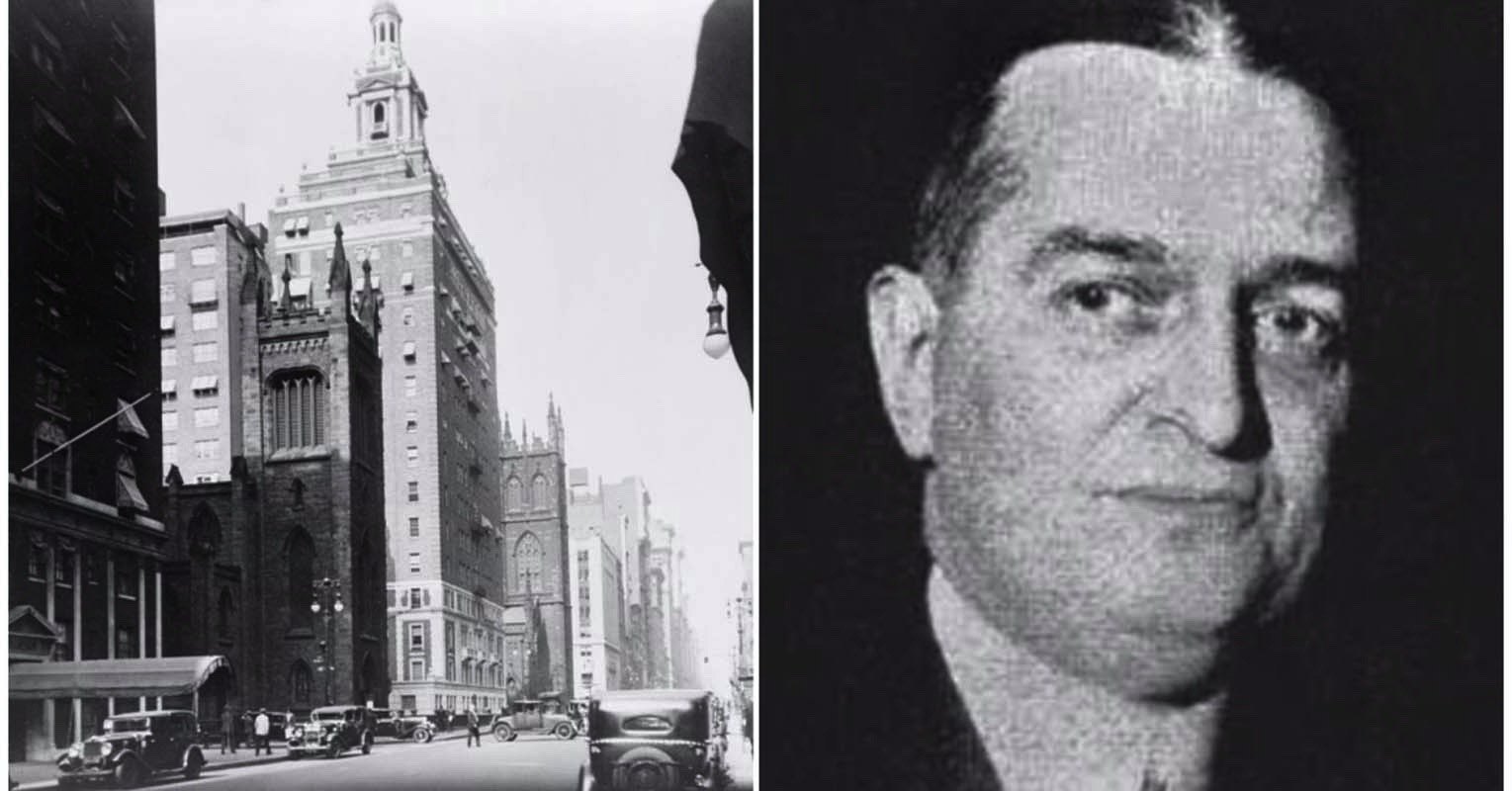

The life of Joseph Force Crater is one full of mysteries. Born in 1889 to Irish immigrants in Easton, Pennsylvania, Crater was the eldest of four children and a graduate of Lafayette College and Columbia University, from which he received his law degree in 1916. During his time at Columbia, Crater would meet his future wife Stella Mance Wheeler — whom he helped secure a divorce. Shortly after, the two would marry in 1917.

Crater’s life would drastically change following his appointment to the New York State Supreme Court by Governor Franklin D. Roosevelt in April 1930. Interestingly, the official candidate put forth by Tammany Hall was passed by in favor of Crater — many believed that Crater, who was known for his sexual rendezvous with showgirls, had paid off Tammany bosses to secure the job.

At that moment, Crater appeared on track to become a prominent political figure, but that same year, he would mysteriously disappear out of thin air. He would leave behind family, friends and a country to wonder where he might be. In death, Crater would cement his legacy in the minds of the public, gaining the illustrious title of “the missingest man in America.” Moreover, his disappearance would send rippling shocks to those around him and the New York City political scene.

The disappearance of Joseph Force Crater

The story of Crater’s disappearance begins in the summer of 1930. At the time, both Crater and his wife were vacationing at their summer cabin in Belgrade, Maine. Following a strange phone call in late July, Crater informed his wife that he was needed back in the city to “straighten those fellows out.” Offering no other information to Wheeler, Crater would leave the next day, making a pitstop at his 40 Fifth Avenue apartment before heading to Atlantic City. There he would convalesce with his mistress, showgirl Sally Lou Ritzi (who went by the show name Ritz on stage), before returning to Maine on August 1.

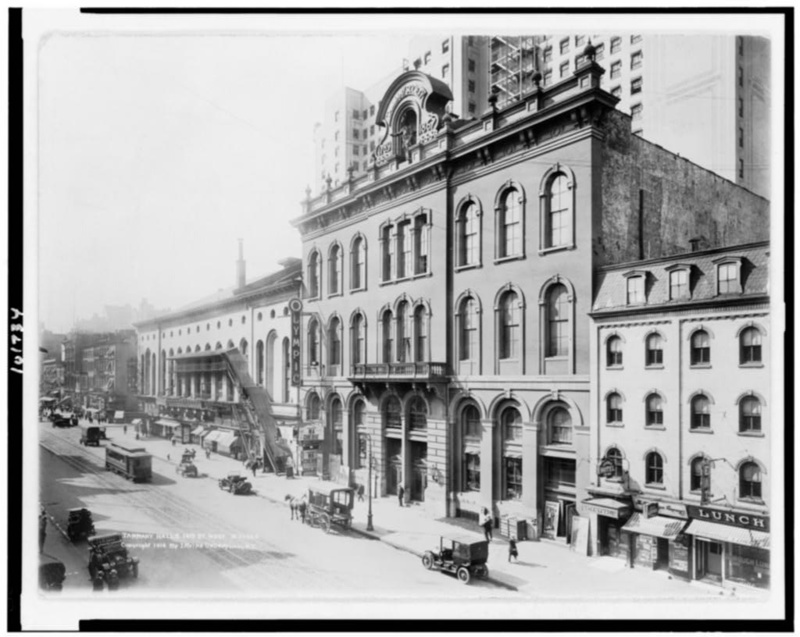

A few days later on August 3, Crater would leave again for New York, with the promise of returning by his wife’s birthday on the 9th. Crater’s departure sparked no concerns for Wheeler, with her viewing him as having been in good spirits. On the morning of August 6, Crater began the day by going through files in his chambers, supposedly destroying several documents in the process. Afterward, he made his law clerk Joseph Mara cash in two checks for $5,150 (today $79,784). The morning would end with Crater and Mara carrying two locked briefcases to his apartment around noon. Crater would then buy a Broadway ticket to see the comedy Dancing Partner at the Belasco Theatre. He would head to dinner with Ritzi and William Klein, a lawyer friend, at Billy Haas’s Chophouse at 332 West 45th Street.

Originally, Klein testified that after the end of dinner, Crater got into a taxicab at 9:30 p.m. outside the restaurant, driving away west on 45th Street. Ritzi corroborated this testimony at first, but later both changed their story, stating that they had been the ones to enter the taxicab, leaving Crater behind. Regardless of how the actual events of the night transpired, it would be the last time anybody would see Crater in the flesh.

At first, nobody took notice of Crater’s disappearance. After not returning to Maine for over 10 days, Wheeler began making various phone calls to Crater’s New York friends in the hopes of finding him. It would not be until Crater failed to appear for the opening of the courts on August 25 that a private investigation would begin. By September 3, police were notified and Crater’s story made national headlines. What might have been crucial leads — such as Crater’s empty safe deposit box and his two missing briefcases — ultimately led to nothing. With millions of Americans positing that they had seen Crater, any potential leads were lost in the fold.

A month later in October, a grand jury investigation was convened to uncover the tragedy. Despite containing more than 95 witnesses and 975 pages of testimony — making it one of the biggest missing person cases of the 20th century — the trial concluded that there was insufficient evidence pointing to whether Crater was dead or alive. The final tangible trace of Crater would be uncovered on January 21, 1931. Crater’s wife found a series of envelopes filled with stocks, bonds and a note in Crater’s dresser drawer which had previously been empty when it was examined by the police for the investigation. Unfortunately, this evidence did nothing to move the search forward. Theories as to what happened to Crater ranged from the tangible to the extreme — some even believed he had decided to flee town with another woman. Crater would be declared dead in 1939 and the case would officially be closed 40 years later in 1979.

The impact of Crater’s disappearance

For Wheeler, hardship and happiness lay in her future, Upon the loss of Crater’s income, Wheeler lost hold of their Fifth Avenue apartment and lived off of an income of just $12 earned from working as a telephone operator in Maine. She would go on to meet her third husband Park Kunz, a New York electrical contractor, marrying him on April 23, 1938. The two were not meant to last, with Wheeler separating from Kunz in 1950. She would pass away at the age of 70 in 1969.

However, what’s most intriguing about Crater’s disappearance is not so much the incident itself but the impact it had on the lives of three women: June Brice, Vivian Gordon, and Sally Lou Ritzi. Following the events of August 1930, Ritzi fled the city and was found living in Youngstown, Ohio in September, citing that she had left following news of her father’s illness. For years, not much was known about the remainder of her life, but that all changed in 2014. Following the publication of The Wife, the Maid, and the Mistress, author Ariel Lawhorn received an intriguing email from Bert Weist, announcing herself as Ritzi’s granddaughter. Weist recounted her grandmother’s story, stating that after leaving, Ritzi changed her name, got married and had a child. Rather than meeting a fate as tragic as her lovers, Ritzi would go on to lead a relatively healthy and successful life before dying peacefully in 2000.

For showgirl June Brice, her fate would be much crueler. Following Crater’s disappearance, speculations as to Brice’s involvement began to circulate, since she had been seen talking to Crater the day before. Wheeler’s lawyer believed that Brice was at the center of a scheme to blackmail Crater — which would explain why Crater cashed in his checks on the day of his disappearance. Moreover, the lawyer postulated that Crater was potentially killed by a gangster boyfriend of Brice’s. On the day the grand jury trial was set to begin, Brice disappeared and would be found years later in 1948 living inside a mental hospital.

As a high-end prostitute, Vivian Gordon’s connections stretched across the city’s influential business people, including city gangster Jack “Legs” Diamond, organized crime figure Arnold Rothstein, and American Madam Polly Adler. On February 12, 1931, Gordon would lose custody of her 16-year old daughter as the result of a conviction, related most likely to one of her numerous property holdings tied to illegal activities. In response, Gordon, with the person in charge of leading an official inquiry into city government corruption, offered to testify about police grafts. Five days later she would be murdered. Gordon’s death and the ensuing publicity would bring turmoil to the city. A policewoman accused of framing Gordon would resign from her position. The once all-powerful Tammany Hall — a prime engine for graft and political corruption — would lose its grip on the city, forcing then-Mayor Jimmy Walker to resign.

Where is the case today?

Today, the disappearance of Joseph Force Crater still remains a mystery, but many have continued to speculate on what happened that fateful summer night. Following the death of Stella Ferrucci Good on August 19, 2005, a shocking revelation was released to the public. Authorities revealed that they had received notes written by Good in which she claimed that her husband, NYPD detective Robert Good, had learned that Crater was killed by Charles Burns — an NYPD officer who worked as a bodyguard for Murder, Inc. enforcer Abe Reles — and Burns’ brother. Moreover, the letter claimed that Crater’s body had been buried near West Eighth Street in Coney Island. However, excavation of the site to find Crater’s remains was not possible, as the area had already been razed during the 1950s to build the current New York Aquarium. With no police records from the time indicating that any skeletal remains were found, the last of the case’s evidence ran dry.

Despite this, Crater’s story has become ingrained into the popular lexicon. One popular phrase which emerged was “to pull a Crater,” colloquially meaning to disappear — though it is no longer widely used today. In addition, many nightclub comedians would use “Judge Crater, call your office,” as a standard gag for many years following his disappearance. Crater has also been referenced in numerous television shows including “M.A.S.H,” ” Golden Girls,” and “Archer.”

Next, check out 10 of NYC’s Unsolved Mysteries!