The 1896 Eastern North America Heat Wave That Helped Spark Theodore Roosevelt’s Career

Today marks the 125th anniversary of the eastern North America heat wave, which wreaked havoc across many of the region’s major cities including New York, Boston, Newark and Chicago. Over a period of 10 days in August 1896, temperatures averaged at least 90 degrees Fahrenheit coupled with 90% humidity and little wind. At night, temperatures never dropped below 72 degrees, with three consecutive nights at 80 degrees or above. As the Boston Globe reported, “No warm wave which has visited this country in recent years has held out longer, has been more continuous in its intensity, or more fatal in its results. Not only has it piled up the death rate to alarming proportions, but it has kept all humanity sweltering in perspiration and maddening heat.”

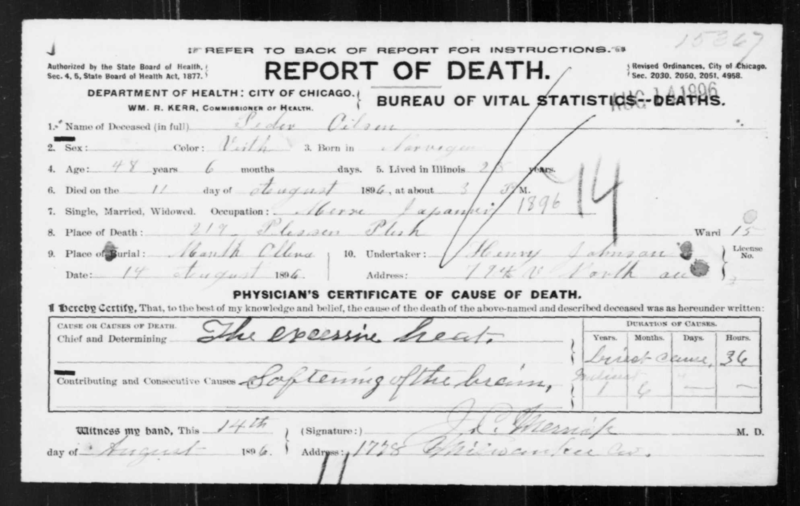

The 1896 eastern North America heat wave resulted in over 1,500 deaths, killing more people than the New York City draft riots of 1863 and the Great Chicago Fire combined. Despite its high death toll, the heat wave is far less known, due in part to the type of people it most affected. The eastern North America heat wave had a particularly damaging impact on the working poor who had far fewer resources to protect themselves.

With the country embroiled in a three-year economic depression known as the Panic of 1893, many New Yorkers at the time were unemployed. Coupled with this was a rise in immigrants, filling squalid tenements in the Lower East Side to the brim. Teeming with recent arrivals who struggled to feed themselves, these tenements served as major breeding grounds for disease. These effects could have potentially been mitigated, but in the 1890s — decades prior to the reforms of the New Deal — there was little to no social safety net for the poor. At the time, government officials often eschewed their responsibilities to the destitute, hungry and unemployed, and it was widely believed that the government should not be involved in supporting people in their day-to-day lives.

In addition, the sordid conditions of tenement living would have an even stronger impact on the heat wave’s high death toll due to a Parks Department city-wide ban on overnight sleeping in public parks. As a result of the ban, many New Yorkers seeking refuge from the sweltering heat inside their cramped apartments turned to more inventive sleeping locations — each more dangerous than the next.

As Edward P. Kohn, professor of American history at Bilkent University in Ankara, Turkey, explains in his novel Hot Time In The Old Town: “They took to the rooftops, and they took to the fire escapes, trying to catch a breath of fresh air. Inevitably, somebody would fall asleep or get drunk, roll off the top of a five-story tenement, crash into the courtyard below, and be killed. You’d have children who would go to sleep on fire escapes and fall off and break their legs or be killed. People [tried] to go down to the piers on the East River and sleep there, out in the open — and would roll into the river and drown.”

Following the end of the heat wave, the ban would be removed. Ultimately it would be a combination of poor living conditions, poor working conditions, poor diet and poor medical care that set the stage for the heat wave’s monstrous impact.

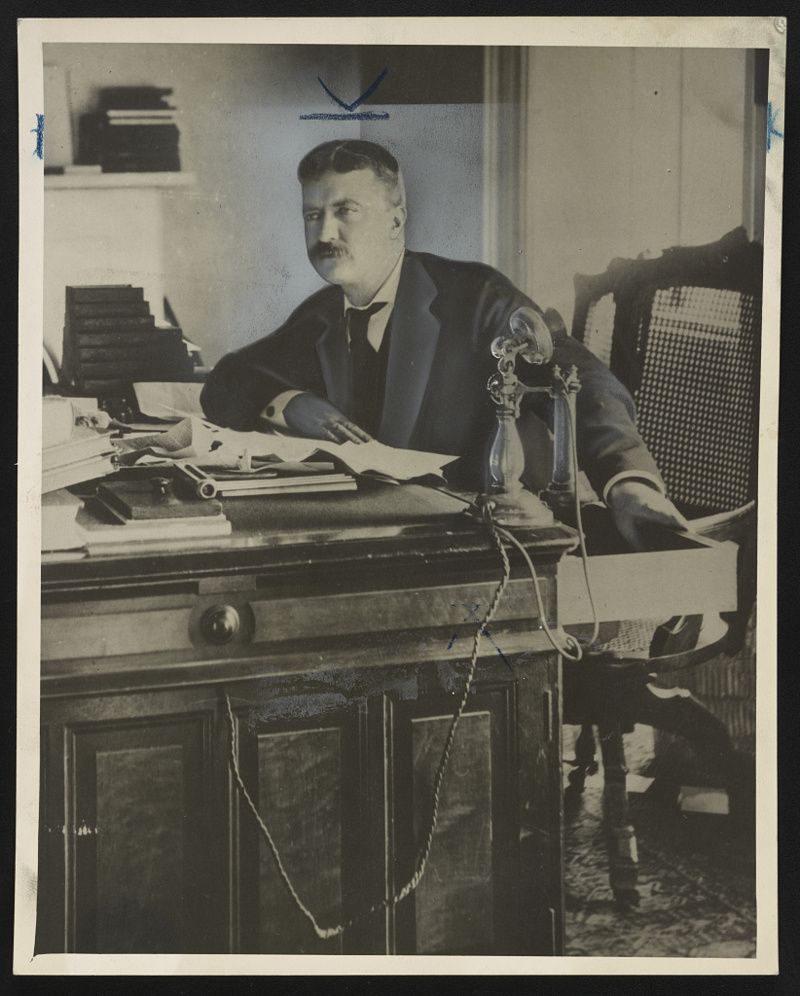

It wouldn’t be until the very last day of the heat wave that New York City’s mayor William Strong would call an emergency meeting with department heads to combat the high temperatures. At the end of the day, there were only a few city officials who would do anything to mitigate the effects of the heat wave. One such individual was the city’s Public Works Commissioner, who ordered worker shifts to be modified so that people worked during the coolest parts of the day. The Commissioner also opened various fire hydrants across the city to provide cold water in an attempt to cool down the population.

Another figure who championed efforts to help New Yorkers during the heat wave was Police Commissioner Theodore Roosevelt. To provide relief to the public, Roosevelt proposed that ice should be distributed across the city for free. In a time before the invention of air conditions, ice was an essential commodity during the summer to keep the body cool.

However, ice had been priced out of reach for poor New Yorkers due to an “Ice Trust.” This trust began in 1896 when American businessman Charles W. Morse bought up the largest of New York’s ice companies and gained the nickname “Ice King of New York.” In the years leading up to 1890, ice in New York remained relatively cheap, since it was easily harvested from the nearby Hudson River and lakes of Rockland County. However, an abnormally warm winter in 1890 resulted in less ice production, leading New Yorkers to turn north for the commodity. Maine’s ice would enter into the New York market, a move Morse capitalized on. Morse would begin slowly buying smaller ice companies in Manhattan, Brooklyn, Yonkers, Long Island and Montauk to take full advantage of the market. Over the years, Morse would bring together the city’s largest and smallest companies, finally forming Consolidated Ice Company in Maine in 1895.

Consolidated took advantage of the increased demand, raising its price from 20-25 cents to 40 cents. With the price doubled, the results were catastrophic, leaving the poor with no access to the potentially life-saving item. In supervising the distribution of ice for free to the city, Roosevelt not only bypassed the trust’s influence but also had direct contact with the city’s working poor. He would recount his experiences during the heat wave in his memoir, intimately remembering the “gasping misery of the little children and of the worn-out mothers.” This experience would shape Roosevelt’s future Progressive-oriented policies, as he would go on to fight for tenement reform. As Kohn viewed Roosevelt: “He was an urban reformer. His origins are in New York urban politics. His roots ran deep into the soil of Manhattan, and for the rest of his life, he considered himself a New Yorker.”

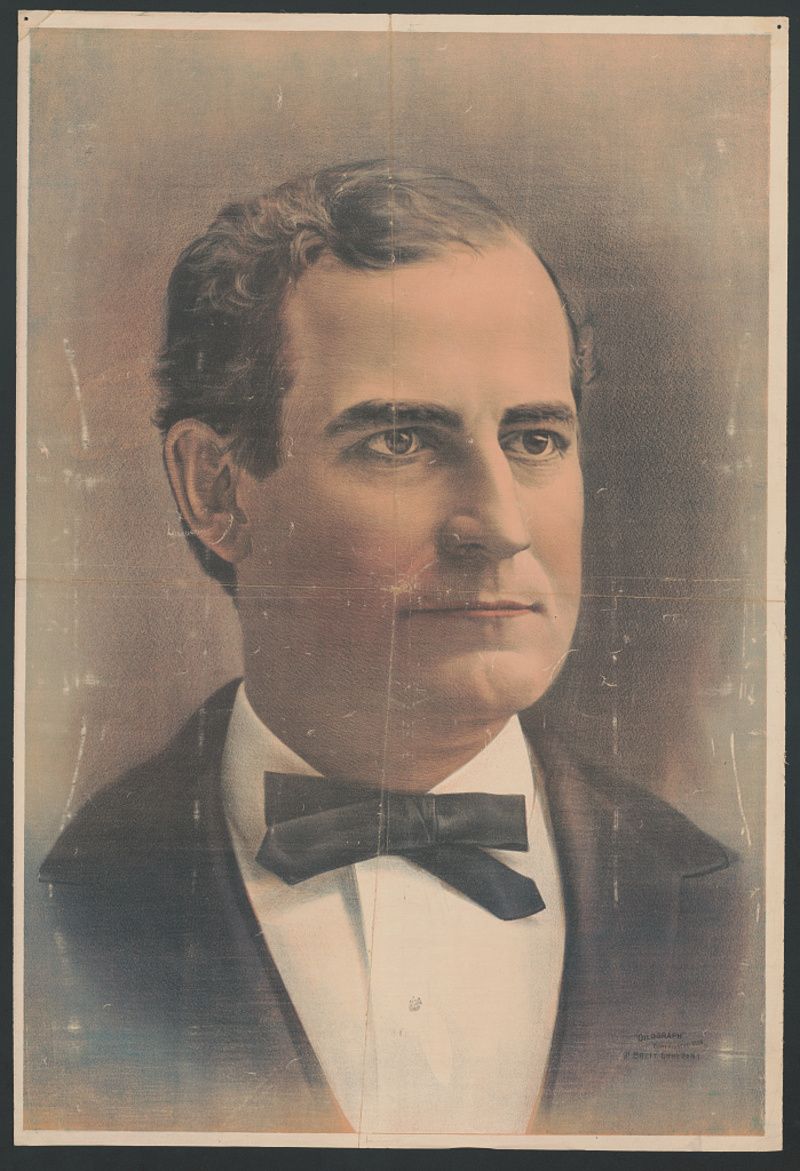

While the 1896 eastern North America heat wave may have served as an important stepping stone for Roosevelt’s political career, it would help spell the end for William Jennings Bryan’s bid for the presidency. During the height of the heat wave, Bryan arrived in New York to officially accept the Democratic nomination at a massive rally in Madison Square Garden. An emergency hospital was set up in the basement as a precaution for expected cases of heatstroke and exhaustion.

However, Bryan’s speech helped the city avoid a public safety disaster. Coupled with the temperature inside the building, which reached well over 100 degrees, Bryan dryly read his speech from a manuscript — injecting none of the enthusiasm or vigor that would have kept his audience invested. Consequently, thousands of New Yorkers ended up leaving early. The speech would go on to be called a failure by all, and a further tour throughout New England would be canceled by Bryan’s campaign manager. In November, he would lose the presidential election to Republican nominee William McKinley.

While the 1896 eastern North America heat wave highlighted the dangers of inadequate responses to temperature surges, many of the lessons learned during the pandemonium were quickly forgotten. Ice would not be given away for free in the city again until a 1919 heat wave more than 20 years later. During a 1972 heat wave, 900 New Yorkers would pass away. Outside of the United States, a 2003 European heat wave would kill over 50,000; this same heat wave would cause the Northeast blackout of 2003 — leading to major power outages across the northeastern and midwestern United States for days.

Next, check out 1o Indoor Public Spaces To Escape The Heat Wave In NYC!