On July 26, 1976, Jody Valenti and Donna Lauria sat in a parked car in the Pelham Bay area of the Bronx. The young women, both just 18 years old, were immersed in a conversation when David Berkowitz shot three bullets into the car. Moments later, Lauria was dead and Valenti was severely wounded. A string of murders similar to this would occur throughout New York City over the next year, imbuing fear in residents from all five boroughs. It was not until Berkowitz left a note at a murder site that the world learned his preferred name: Son of Sam. .44 caliber bullets, a parking ticket, eyewitness accounts, and suspicious neighbors would eventually lead to his downfall — 44 years ago today.

Berkowitz was born on June 1, 1953, in Brooklyn. His birth mother, Betty Falco, put him up for adoption shortly after his birth. Pearl and Nathan Berkowitz, a Jewish couple living in the Bronx, adopted him and raised him as an only child. After Pearl Berkowitz passed from cancer in 1967, David Berkowitz found struggled to cope and move forward.

Following high school, Berkowitz enrolled in the army. He served for three years until he was honorably discharged despite occasional tardiness, use of amphetamines and LSD, and frequent theft from the dining hall. While in the army, he improved his gunman skills as a sharpshooter and was labeled “an outstanding and dependable soldier.”

Upon his return to New York City, Berkowitz worked as a security guard and taxi driver, along with enrolling in Bronx Community College. During this time, he set 1,488 fires throughout New York City. He never faced punishment for these fires and maintained a detailed log of each incident. Days after his final fire, Berkowitz attempted to kill two young women with a hunting knife. The first woman escaped unidentified, and the only proof that an attack on her occurred is because Berkowitz claimed it happened. Later that evening, he attacked 15-year-old Michelle Forman. Despite several wounds in her hand and torso, she survived. From here, Berkowitz’s murder spree approached rapidly.

After moving several times since his return to New York City, Berkowitz settled in an apartment at 35 Pine St. in Yonkers. One of his neighbors, Sam Carr, owned a black Labrador retriever named Harvey who, according to Berkowitz, ordered him to murder. Berkowitz claimed Carr was a powerful demon who delivered demands through his demon-possessed dog. In 2013, Berkowitz reversed this narrative by claiming the dog had never given him orders. He also denied being part of a demonic cult in an interview with CNN.

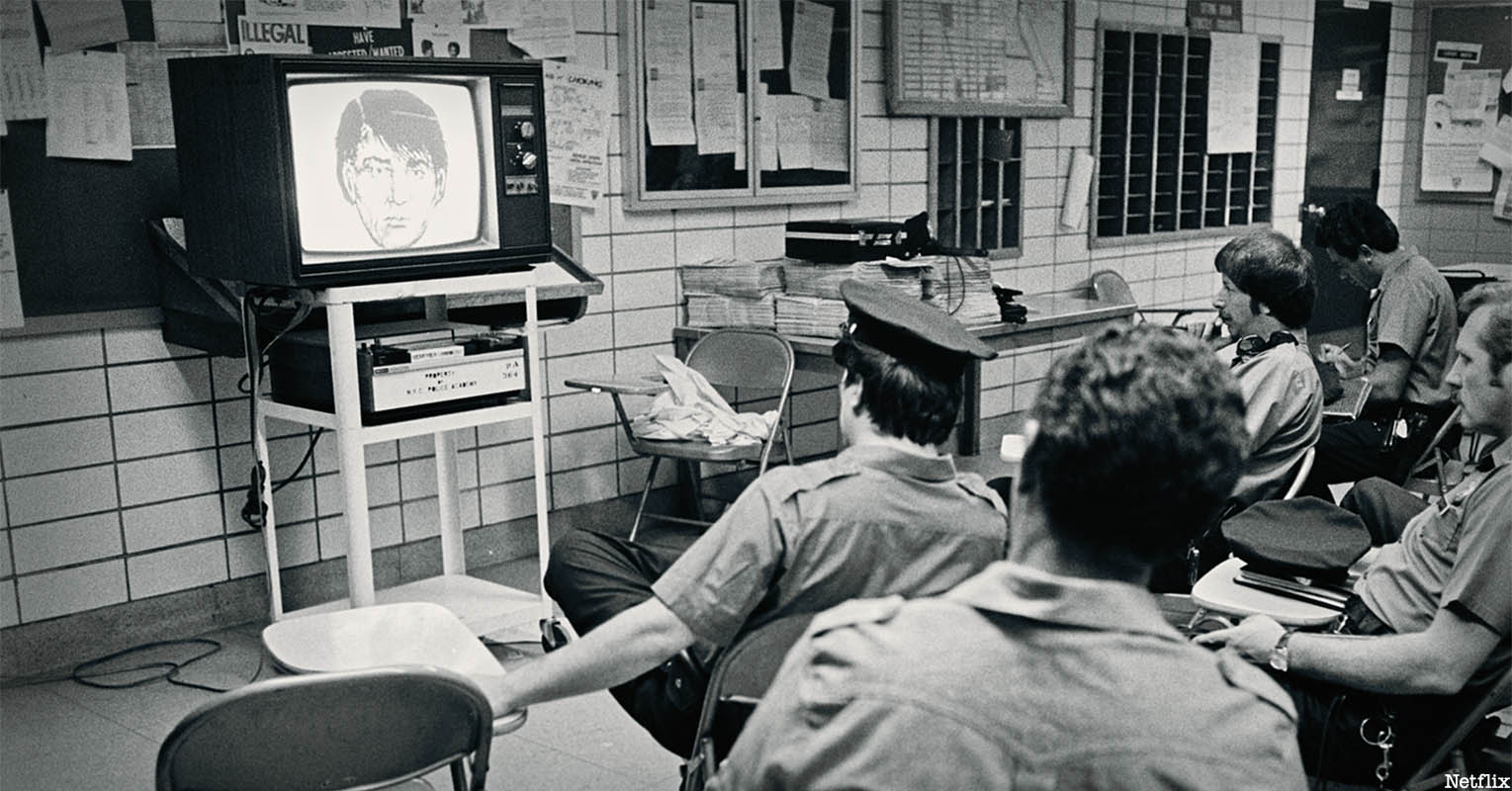

Nevertheless, after quitting his job as a security guard, Berkowitz committed his first murder by killing Lauria and Valenti. Three months later, he wounded Carl Denaro as he spoke to a friend in his car. A month after, Berkowitz shot Donna DeMasi and Joanne Lomino as they walked home from a theater. No one suspected a connection between the three crimes, but DeMasi and Lomino provided an eye-witness account that the police used to make the first composite sketch of David Berkowitz.

When Berkowitz killed Christine Freund on January 30, 1977, as she sat in a vehicle with her fiancée, the police began to look for a connection between the string of attacks. The .44 caliber bullets found at the scene led the police to call the killer the “.44 Caliber Killer.” When Berkowitz took another victim five weeks later, the police found bullets that matched that of the Freund murder. The victim was Virginia Voskerichian, a Columbia University student walking through Forest Hills, Queens.

Following this attack, fear overtook New York City. Women cut and dyed their hair to stray from the lengthy brunette style most of the victims sported. The New York Daily News reported that mistreatment of one of Berkowitz’s relatives by a long, dark-haired nurse may have influenced Berkowitz’s preferred demographic. Nevertheless, few sat in vehicles with their lovers, walked around at night or went to nightclubs.

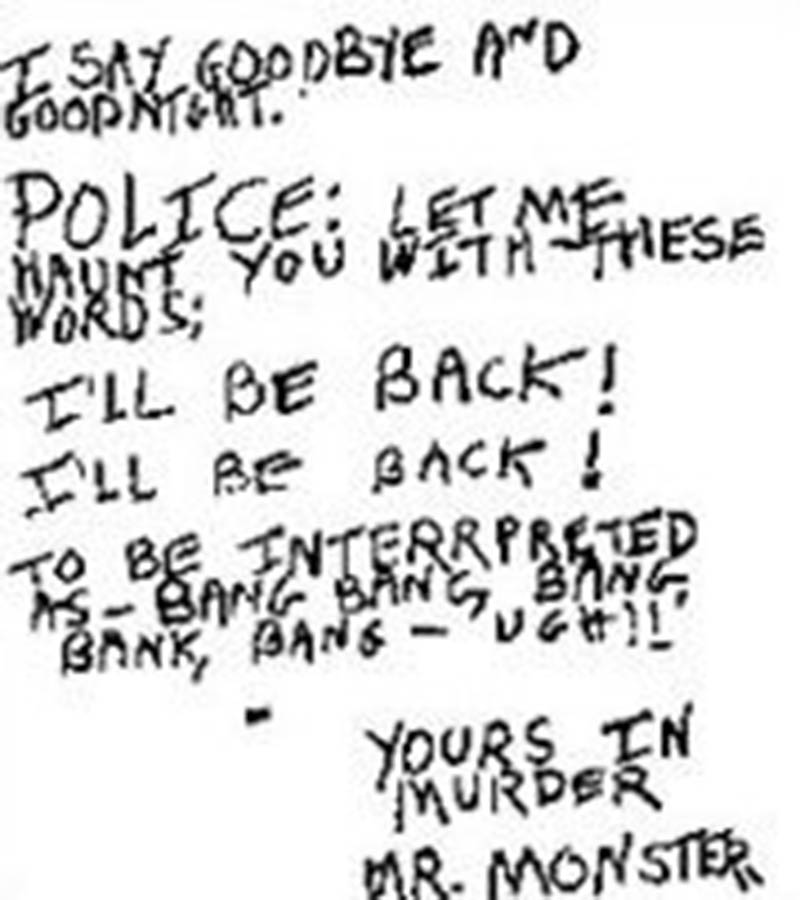

During his next attack on April 17, 1977, Berkowitz left a letter with his victims Valentina Suriani and Alexander Esau. In the letter, he declared himself the “Son of Sam” for the first time. He later wrote a letter to New York Daily News reporter Jimmy Breslin that Breslin published before showing to the police.

At the time, the “Omega” police force tasked with capturing the killer was investigating ledes and patrolling the streets. After Berkowitz shot Carr’s dog Harvey and sent strange letters to his neighbors, they reported him to the police. However, overwhelmed with “Son of Sam” reports, the police did not investigate Berkowitz further. On June 26, he wounded two more young women walking home from a disco.

The one-year anniversary of the first “Son of Sam” murder passed with peak police surveillance and no murders. Two days later, Berkowitz moved his attacks to Brooklyn for the first time. He shot Stacy Moskowitz and Robert Violante; only Violante survived. An eyewitness provided a more solid sketch for Berkowitz and a fact that would lead to his capture: the murderer fled the scene in a car with a parking ticket. The police had issued only a handful of tickets that night, including one to Berkowitz. His name matched the additional reports provided by his worried neighbors.

“A lot of people seem to believe that we were connected with the killings — really connected,” Sam Carr’s wife told the New York Times. “People don’t seem to know that for months before he was arrested he had harassed us with letters and anonymous phone calls and we believe he was the one who threw a molotov cocktail at our house last Oct. 4. We had been nervous and frightened for months before and in the aftermath were still on edge and emotionally upset.”

After staking out his apartment on Pine Street, the police arrested Berkowitz on August 10, 1977. They stopped him as he exited his home with a semiautomatic rifle. He claimed he was on his way to commit another murder. Up until his arrest, he worked as a letter sorter at the Bronx General Post Office by Yankee Stadium.

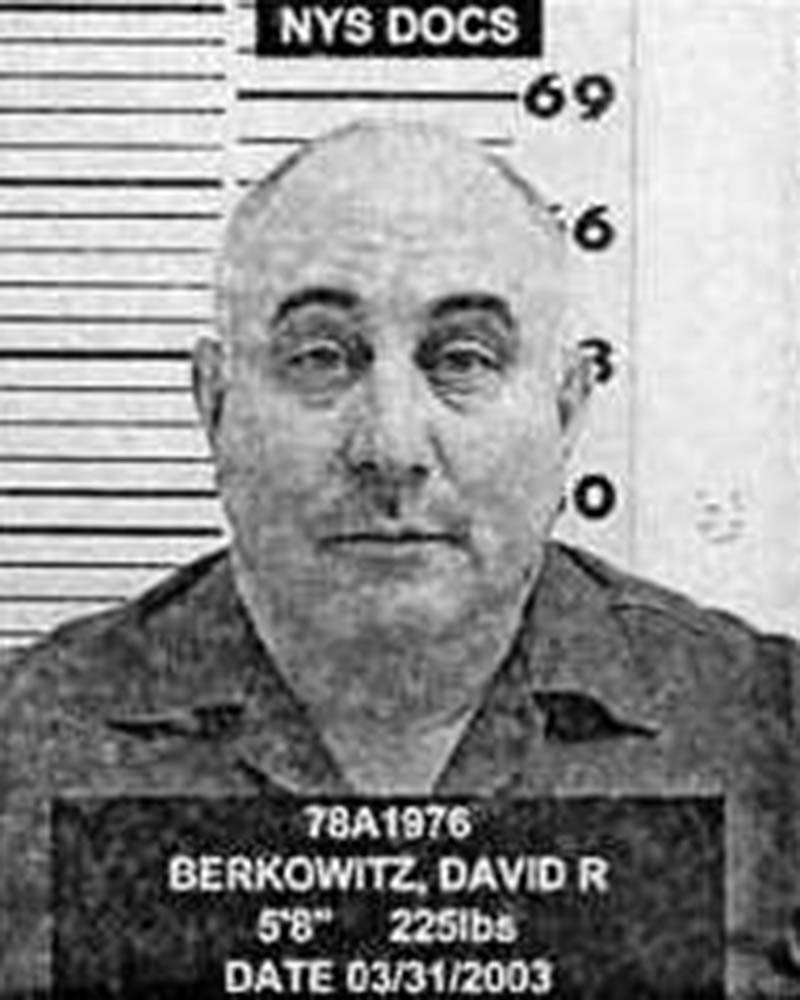

Despite an initial insanity plea, the court declared him mentally fit for trial. He pleaded guilty to six murders and is still serving the six 25-years-to-life sentences given to him in court. Currently, Berkowitz is in the Shawangunk Correctional Facility in the Hudson Valley, and a psychologist diagnosed him with paranoid schizophrenia. Several movies and books have been released about Berkowitz, but the “Son of Sam” laws prevent him from receiving profits from these published works.

Now, 44 years after his arrest, Berkowitz calls himself the “Son of Hope.” After a fellow inmate pushed him to accept Jesus, he let God “take control” of his life. In a journal uploaded monthly on his website, Berkowitz shares his thoughts about life and God along with setting “the record straight.”

“I was involved in the occult and I got burned. I became a cruel killer and threw away my life as well as destroyed the lives of others. Now I have discovered that Christ is my answer and my hope,” Berkowitz wrote in a testimony on his website. “He broke the chains of mental confusion and depression that had me bound. Today I have placed my life in His hands. I only wish I knew Jesus before all these crimes happened – they would not have happened.”

Next, check out the mysterious murder of Mary Cecilia Rogers!