The Berkshires Bowling Alley that Inspired "The Big Lebowski"

It’s been 36 years since the release of The Big Lebowski, the irreverent cult comedy by Joel and Ethan

Untapped New York is very excited to announce our partnership with Madame Architect for a new interview series. Madame Architect is “an online magazine celebrating the extraordinary women that shape our world, a magazine designed to break the architect’s mold and show young women entering the industry the myriad choices they have in crafting a dynamic, meaningful, and interesting career.” It was founded by Julia Gamolina, who has to date published over 250 interviews with women who advance the practice of architecture.

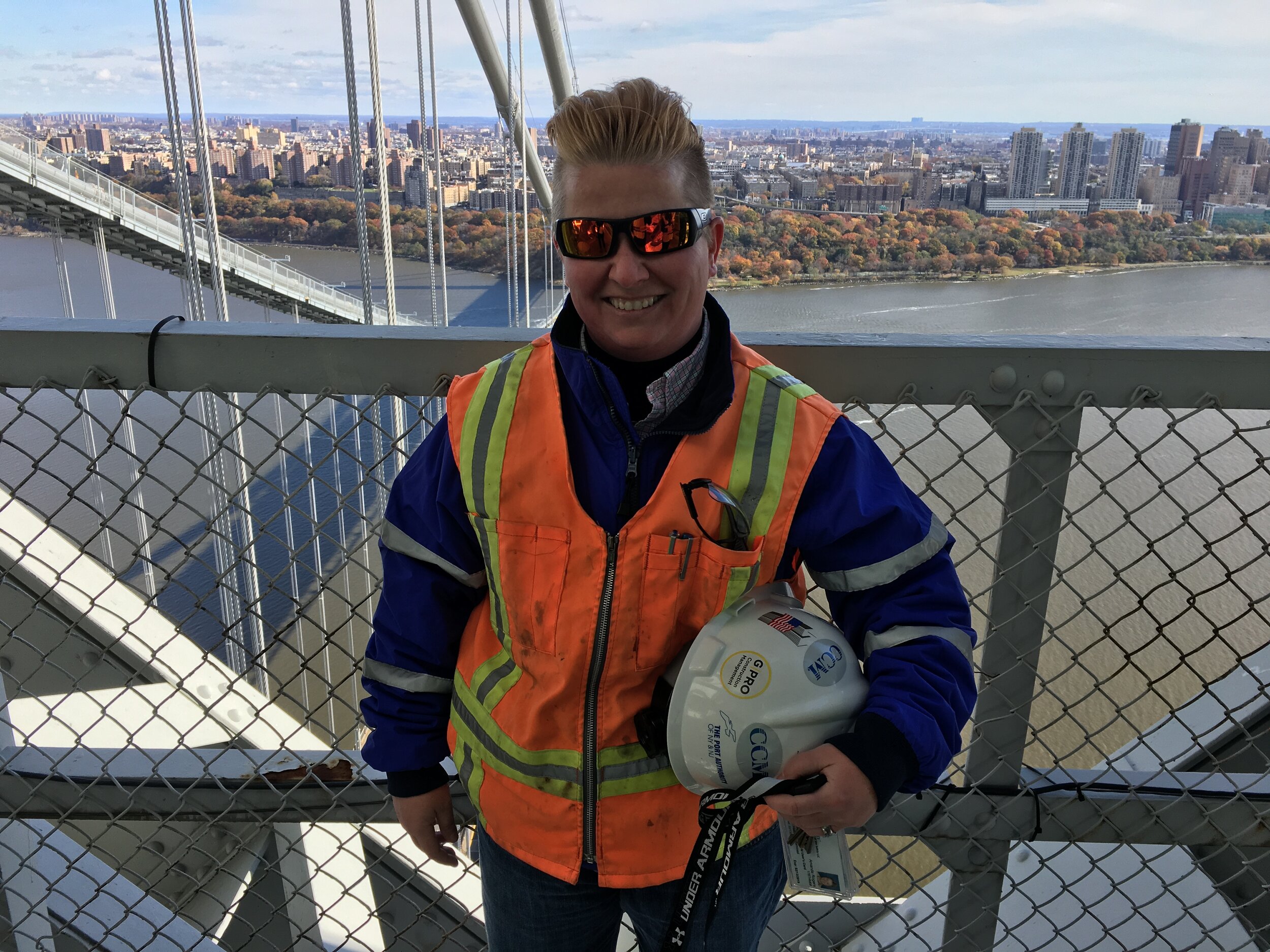

#TodayinInfrastructure: Amanda Rogers’ interview kicks off our partnership with Madame Architect to bring you interviews with the people behind today’s infrastructural innovations — and who also happen to be women. These specialists are innovating in ways that are often hidden, whether it be underground, underwater or so integrated into the cityscape that one cannot immediately recognize the design’s profound impact. Follow along for many more interviews to come, and enjoy this conversation with Amanda.

Amanda Rogers is the Deputy Chief of Construction & Chief of Aviation Construction within the Engineering Department at the Port Authority of NY & NJ. Rogers has extensive experience on major capital programs including alternate delivery methods such as the $1.9 billion Restore the George program, LaGuardia Airport redevelopment and JFK AirTrain. Rogers was the Engineering Department’s Construction Management Lead Engineer responsible for the Restore the George program from 2016 through 2019. The nearly $2 billion capital program consists of 12 construction contracts over 9 years to rehabilitate and replace many critical aspects of the George Washington Bridge, inclusive of replacing the suspender ropes, the PIP Helix and the rehabilitation of the 178th & 179th Streets.

Prior to joining the Bridges and Tunnels facilities, Rogers served as an Engineer of Construction at LaGuardia Airport, where she played a vital role in completing the infrastructure projects to prepare for the selection and award of the PPP Redevelopment Program. Prior to that, Rogers served as the Resident Engineer at John F. Kennedy Airport. Rogers started her career at the AirTrain Terminal at Jamaica Station. She was responsible for coordinating with the Long Island Rail Road, general field inspection and contract administration. Rogers is a graduate of Manhattan College with a degree in Mechanical Engineering, and she is a licensed professional engineer, a certified construction manager and a LEED accredited professional. In her conversation with Julia Gamolina of Madame Architect, Rogers talks about the complex aspects of the various infrastructure projects she’s been involved with in NYC, advising those just starting their careers to step up to challenges to work on that which they want to.

JG: I’d love to start from your early days — how did you grow up, and what did you like to do as a kid?

AR: I loved sports and was very sports-driven. It was a huge part of my childhood and my family’s childhood — my brothers played football and lacrosse, and my sister and I played field hockey and softball. My poor parents drove us all over to get us to all of those games.

I think that foundation worked well for a future in the engineering and construction industry — that sports mentality of it taking a team, that we all have the same goal in mind, it doesn’t really matter how you get there, just that you get there together. The work ethic from sports played a big part in me being successful in this world, or for that matter, any professional environment. The mindset of showing up on time, rolling up your sleeves, doing your best, and admitting when you have a failure because everybody has them. How you deal with those failures determines whether you’re successful or not.

We were actually onboarding Lesley Braxton, a new colleague of mine at Trahan recently, and she said something like, “I love where you are in your career because you had enough time to get experience and confidence under your belt but you also haven’t yet failed enough. In five more years or so, you’ll really have been through it.” I love that she said that because setbacks and things not going as you might like them too are a really important part of any process. I’m happy you touched on that.

Absolutely. I think in my world, especially working for the Port Authority, we bring kids right out of college, and we tell them right from the get-go, “You’re never going to get in trouble for making the wrong decision. If anything, we’re going to get upset if you don’t make any decisions.” And most of what we learn is sometimes we don’t make the right decision and that’s okay, we’re going to fix it, but you have to have that kind of stomach to make the tough decisions in the moment.

What within engineering did you eventually study?

Mechanical engineering at Manhattan College. I liked the compositions of metals and the really geeky, technical stuff, so I gravitated towards that when I was going for my PE license. Most mechanicals were going for HVAC type stuff, and I remember thinking, “No, I want to go for the mechanics of materials,” which is like welding, bolting, very structural, very nitty gritty type stuff. I just find it very interesting. My older brother is a machinist, so we don’t talk about sports anymore; now we talk about metals and new technology and machining metals and stuff like that. [laughs]

What did you learn in studying mechanical engineering, both about the field and about yourself?

What I really took out of engineering school is that engineers are going to learn their whole lives. You’re never going to master anything, you’ll always need to know how to figure it out and problem-solve. Part of why I like the construction field so much is because you’re constantly solving problems. To be honest, in twenty years I rarely see the same problem twice. It’s always new, it’s always fresh. As an engineer, the best thing that you can pull out of engineering school is time management and figuring out that you could teach yourself things.

Architecture is very similar in that way. People talk about architects being constant learners, especially given that the documentation technologies are changing so rapidly.

When I was in high school, we had some electives, and I had my choice between taking a sewing class or a drafting class. And I feel like I’m not old, but when I tell people my first drafting class was literally with pencils and vellum —

Mine too! [laughs]

When you tell people about that, you’re like, “Wow what version are we on now!” I don’t even know the latest version of AutoCAD, it’s crazy.

I miss vellum.

There’s nothing more rewarding than hand-drawing and seeing it turn into a project. I’m working on the George Washington Bridge right now and some of the old prints from the 1930s — there are hand drawings and copies of copies of copies — and they’re beautiful.

How did you start out after college?

I came out of college and my first project was the Jamaica Station Transportation Building with the Long Island Rail Road. We were building a seven-story building that tied into the air train that was going to go down to JFK at Jamaica Station with Long Island Rail Road and then rehabbing their portion of their work — their platforms, their canopies, and even a little bit of their building, which is a historical landmark. I went from college, kind of jumped in, at the time it was the biggest project in the Port Authority. Now, looking at the dollars, it’s peanuts.

And then, shortly after I joined, September 11 happened. The person that I was immediately reporting to went down to World Trade [Center] to help with the recovery and efforts down there, and they were looking for somebody to take on what he was doing. He probably had 10 to 15 years of experience at that point, and my boss, who is now the chief engineer of the Port Authority, Jim Starace, looked at me and said, “Do you think you can handle this?”

Me being 22 years old and not knowing what I don’t know, I was like, “Sure I can!” That set the tone for me — I’m going to step up and I’m going to take on every project and every big role that I can and kind of figure it out as I go.

Good for you. That’s a fantastic example of rising to the occasion. What came next?

I did that for about four or five years and then I moved down to JFK Airport, where I was out in the field, handling a bunch of state of good repair projects, taxiway paving, building rehab projects, tenant expansions on terminals, demo projects on hangars — a whole bunch of work down at JFK which I thoroughly enjoyed, and I fell in love with aviation a little bit.

LaGuardia popped onto the radar about four or five years later. I had this pattern of working really hard at something for four or five years and then moving onto a bigger step. So, LaGuardia was happening, and I said, “What do you mean they’re going to knock down the airport and rebuild it at the same time? How is that even possible?” Then a position opened up and they said, “Hey, would you be interested in stepping into this role?”

At the time, I just thought I’d only ever done these small projects, could I really handle something this big? But me not being shy, I said, “Absolutely, let’s give it a whirl.”

Rising again.

I went up to LaGuardia and started working on developing the PPP agreement. I spent about two years writing the documents and meeting with teams and developing the overall master plan for the airport, which was absolutely fascinating, just the smart minds we had to help us get through that.

From there, Restore the George happened. The deputy chief engineer came to me and said, “We really need somebody to head this up and everywhere you’ve gone, you’ve stepped in and done a great job for us. Would you consider going over the bridge?”

I was flattered. Again I said, “Sure I’ll give it a try.” I came over to the bridge and absolutely fell in love with that too. That kind of hunger in you to keep learning and to keep accepting challenges and accepting something — I came in here cold, and I needed to learn how the place operates and what’s going to help me be successful here, what’s not. It was definitely a huge challenge.

For our readers who may not be familiar, tell me more about Restore the George.

It’s a great program, the bridge is approaching 90 years old now. Certain critical pieces were getting towards the end of their useful life. Some studies were done, whether it would be best to rehab the bridge, maybe try and build a new bridge a couple of miles north or south. Obviously, for business reasons, it made sense to rehab the bridge in place.

There are eleven projects in the program, it’s a $1.9 billion program, and we’re doing everything from rehabbing the main cables, replacing the suspender ropes, a lot of steel repairs on both the upper and the lower levels, paving here and there. We did the new Palisades Interstate Parkway Helix — we actually put up a temporary helix to swap traffic over the temporary roadway, knocked down the old one and rebuilt the new one.

The key to being successful with the George Washington Bridge in construction is staging and planning and planning it out six times to make sure that you have plan A, B, C and D because we have a saying here that the bridge always wins; it’s always going to throw you a curveball. It connects two major corridors of this region, so if we have a traffic incident not really on our property but 10 miles down the road, that impacts our work here. So, there are a ton of moving parts, a ton of strategic planning, but it’s a heck of a lot of fun from an engineer’s perspective to try and get work done here.

That’s amazing. Now your focus is on aviation again, with airports. Where are you in your career today with that? You’ve obviously worked on different types of infrastructure now, so what is it about aviation projects specifically that really resonates with you?

I always joke around when we’re at the bridge — I’ll go home at night and if, when I come back the next morning, it looks exactly the same. That’s success in the world of the bridge. In the world of the airport, when you leave at night and you come in the next morning, you’re like, “Holy cow, look what they did last night, it looks drastically different,” and the moods of the people at the airport are very different — they’re going on vacation, they’re picking up a loved one, it has a very good feeling to it. So you have that instant gratification that what you’re doing is making an impact on these people’s lives immediately.

When you’re working on bridges and tunnels, you’re pretty much causing traffic and you don’t get that same feeling immediately, so I think that plays a big part of it maybe. I have friends texting me every single time they fly in and out of LaGuardia, telling me how cool the new terminal is and they can’t wait for it to be done. The same thing at Newark — we’re building a new terminal there. It’s an immediate impact that my family and my friends are going to use. So, how cool is that, that I get to really give back to public needs?

Talk to me a little bit about working with architects. Our readership is primarily young architects, young women that are starting out in their careers. What advice do you have for architects?

[Laughs] I would say to architects that engineers don’t see your vision. And I’m just going to be honest, most of the time in a conversation with an architect, I’m like, “Does it really matter that we’re using ‘blue grey’ rather than ‘grey grey’ or ‘stone grey’ rather than ‘concrete grey’?”

I don’t see that vision, I’m an engineer. I look at function, I look at how we meet the budget and schedule. Most of the time during the project, when we’re working with the architect, we don’t see your vision until it’s complete. Like in LaGuardia, when you see the fountain, and you see the mosaic, and you see the artwork, and the layout and the functionality.

I’m sure architects are frustrated with us, that we are constantly driving budget and schedule, and thinking, “Do we need stainless steel diamond plated, can’t we cut back here and cut back there?” Stay strong — it’s your vision and we’re building your vision, so have that thick skin to deal with us because we don’t see it. That’s just God’s honest truth.

Thank you for that! To your earlier point though, we need both kinds of minds, ultimately, to make the best thing. It’s all a big ecosystem and you need everybody to execute a project well — you need all the parts and pieces. Throughout your career, just in general looking back at everything, what have been the biggest challenges?

Probably, for me, it’s always been a little bit of time management. I think engineers in particular are not good at not being able to complete all your work in one day. I always remember, back when I was five or six years old and I had homework, it was the first thing I did when I got home. I would need to get it done, so especially in the Port Authority, we’re spread pretty thin often, especially as far as technical expertise. So we have a ton of projects, more work than we can handle for the most part, so it’s always time management, trying to pick and choose which fire needs addressing immediately and which one can wait till tomorrow.

What about the highlights? What are you most proud of?

I’m proud of so much. I’m proud of even some of the smaller projects that we do that are not the big and famous LaGuardias or the suspender ropes. The Palisades Interstate Parkway helix was a relatively smaller job, but to try and plan that, it runs over all four levels of the bridge — upper level, lower level, east and westbound. The complexity of trying to plan that out is extremely rewarding.

I have to say LaGuardia is probably my favorite project I’ve ever worked on. At the time, it was the biggest project in the country, and, again, you’re knocking down an airport while you’re rebuilding it — it’s an operation. It’s kind of like performing open-heart surgery on somebody running a marathon — it’s completely unheard of. We’re doing it, and it’s a challenge, and every day is a challenge but anybody that’s flown in and out of there in the last couple of months has definitely appreciated it.

I have! Who are you admiring right now in the world? Who is out there just doing really wonderful work that you would want to make sure everyone knows about?

Every single parent that has managed through the pandemic. I see the stress that everyone that I work with that has young children. Obviously, the nurses and doctors that are getting us through this pandemic as well. The working parent trying to homeschool and take care of themselves, and take care of their children, and take care of both of their mental health. I just absolutely admire it and I have no idea how they’re doing it, but they are. They deserve every shoutout that they can possibly get because not only are they doing the job that I’m doing, but they’re also raising children and homeschooling and doing all sorts of crazy things that I couldn’t even try to imagine taking care of.

I completely agree with you. My last question is, for anyone wanting to work in the built environment, what advice do you have for them?

Come and get it. There’s a ton of infrastructure work that needs to be done, especially in and around New York City and the metro area. There’s a ton of work and there’s a place for everybody, even if you’re not an engineer or an architect and you just want to get involved in projects and project management and cost control and the finance aspect of it.

There’s so much space for everybody and every project I’ve gone on, I’ve been really astonished that it’s not a competitive world here, and we sincerely are all trying to help each other out. I’m willing to take advice from you, you would be taking advice from me. It’s really this mindset of we’ve got more work than we can handle and anybody that can help, we’re more than willing to teach to kind of get you on board and run with it.

Next, check out the Top 10 Secrets of LaGuardia Airport!

Subscribe to our newsletter