After-Hours Tour of "Noguchi's New York" Exhibit

Join an exclusive curator-led tour at NYC's Noguchi Museum!

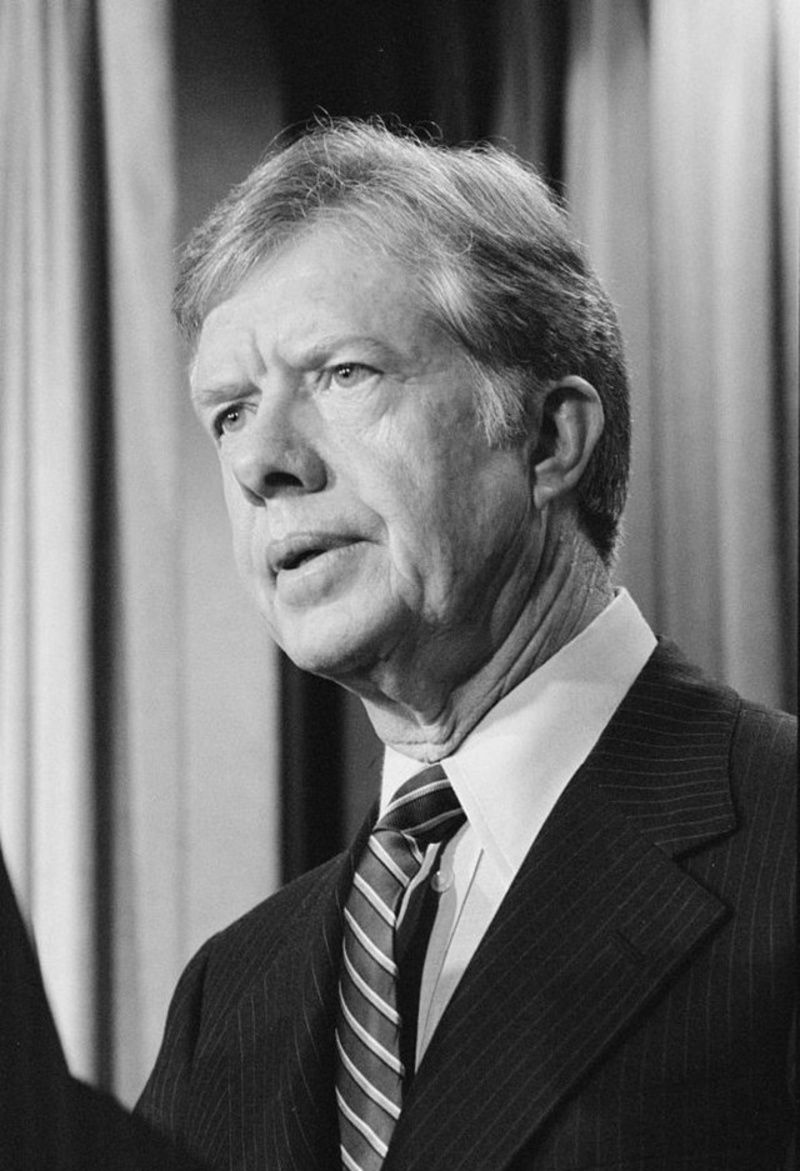

From August 11 to August 14, 1980, the Democratic National Convention was held in New York City at Madison Square Garden. This year, Democratic primary candidates included the incumbent President Jimmy Carter of Georgia, Senator Ted Kennedy of Massachusetts and Senator William Proxmire of Wisconsin. At the end of the convention, President Carter and Vice President Walter Mondale were nominated for reelection, receiving 2,123 or 64% of the delegates’ votes — in comparison to Kennedy’s 34.7% and Proxmire’s 0.3%.

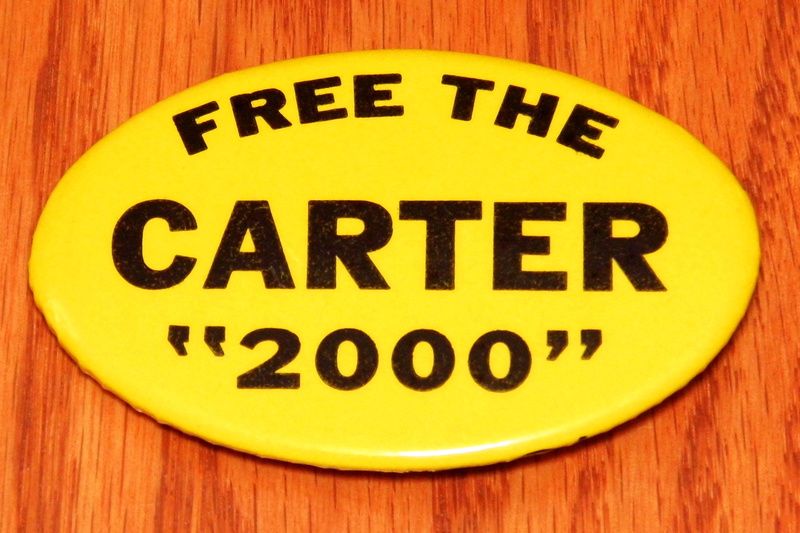

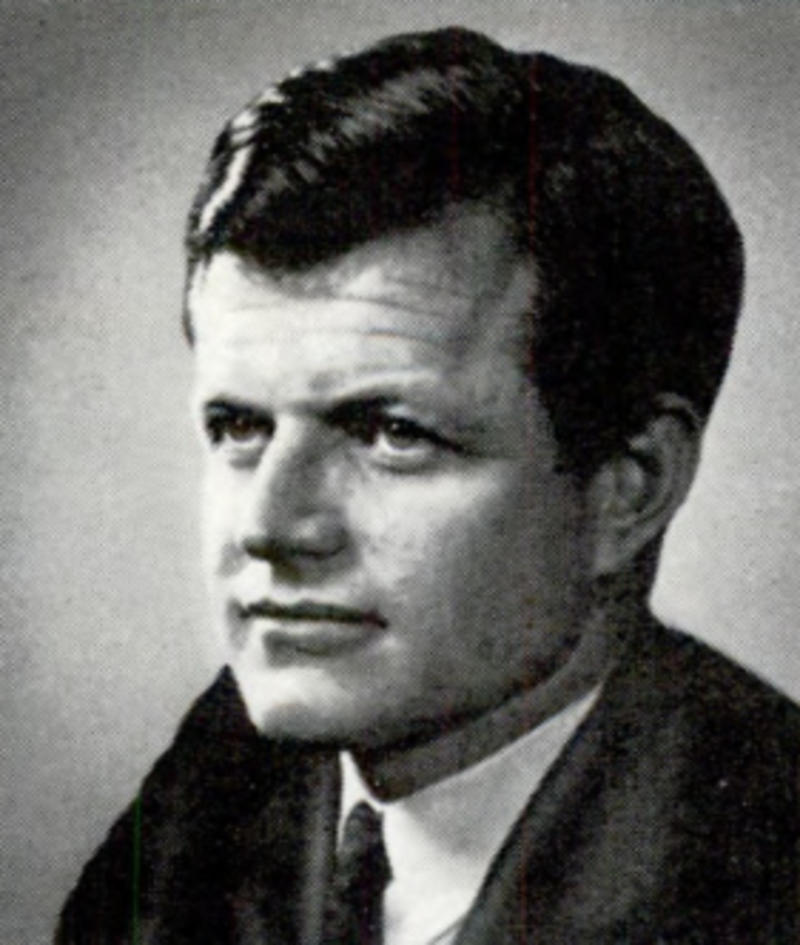

However, the road to Carter’s official nomination at the convention was rife with conflict. As the primary election season moved forward, tension arose between Kennedy and Carter due to their stark differences in policy decisions — Kennedy was interested in moving the Democratic Party to the left, while Carter took a more moderate approach. During the first two days of the convention, Kennedy’s forces attempted to take Carter’s 2,000 delegate votes, but they failed to win a vote in favor of having an open convention. Had an open convention been secured, delegates would have been able to vote for any candidate of their choice regardless of their district’s primary results.

Despite failing to secure this crucial vote — which many believe caused the senator to lose the nomination — Kennedy and his team were determined to embarrass Carter. They did so by pushing a series of policy initiatives that went against the President’s normal agenda. These included a $12 billion stimulus spending program, measures to fight unemployment, and an endorsement of wage and price controls. Voting for these initiatives was set to take place after the delivery of a speech by Kennedy, and Carter’s team worried that this would help to create the perfect atmosphere to push delegates to adopt more liberal policies. After spending the previous day saying “no” to Kennedy whips attempting to get them to change their vote for the senator, the delegates were ready to say “yes” to anything else.

Over the course of August 12th, tension between the two dueling factions grew so intense that two high-ranking members almost broke out into a fistfight. Harold Ickes, manager of floor operations for Kennedy, used an obscure procedural rule to call a halt to the afternoon of floor proceedings — messing up the planned television schedule for the convention. Done out of pure spite, Ickes stated as justification for his actions: “I mean we weren’t thinking about the country. We weren’t even thinking about the general election. It was, F— em’. You know? To be blunt about it.”

The response to Ickes’ move was swift. Tom Donilon, who was in charge of ensuring the convention went smoothly, was furious at the major disruption. Leaving the confines of his office, Ickes charged across the stage, finding Carter a lawyer named Tim Smith grappling with Ickes. The two proceeded to yell and curse at one another, mere seconds away from coming to blows. Their fight came to an end a few minutes later, interrupted by a phone call from Kennedy and his advisors to Ickes — telling him it was time to get on with the convention.

A few hours later, it was time for Kennedy to deliver his speech entitled “The Dream Shall Never Die.” Written by Bob Shrum, the speech defended post-World War II liberalism, advocating for the implementation of a national healthcare model. Lasting 32 minutes, the speech began with a concession of the presidential campaign. Following this, Kennedy immediately distinguished himself from Carter, stating that he had come “not to argue as a candidate but to affirm a cause”; such a cause was to serve “the humble members of society — the farmers, mechanics, and laborers.”

Next, Kennedy directly attacked Regean’s conservative political ideas, arguing that his policies were vehemently against labor unions, urban centers, senior citizens and the environment. He did so by appealing to a nostalgic defense of old liberal values, highlighting that while social programs may become obsolete over time, the core ideal of fairness will always endure. He stated: “The great adventures which our opponents offer is a voyage into the past. Progress is our heritage, not theirs. What is right for us as Democrats is also the right way for Democrats to win.”

To further support his arguments, Kennedy used a technique known as prosopopeia, a rhetorical device in which a speaker or writer communicates to their audience by speaking as another person or object. Throughout the speech, Kennedy would tell real-life stories of people he had met during his campaign, drawing from their experiences to build support for the Democratic Party. Some striking examples from the speech include anecdotes on a glassblower in Charleston, West Virginia, a Trachta family who farmed in Iowa, and a grandmother in East Oakland. Moreover, Kennedy also focused on the sites he saw while on the campaign trail, highlighting closed factories in Anderson, Indiana and South Gate, California, and the impact their loss had on everyday working families.

Toward the end of the speech, Kennedy circled back to the main event at hand, making his only remarks on Carter for the night. However, rather than praising the nominee to bring the party behind him, Kennedy’s words on Carter were rather subdued. “I congratulate President Carter on his victory here. I am confident that the Democratic Party will reunite on the basis of Democratic principles, and that together we will march forward towards a Democratic victory in 1980.”

Following this, Kennedy made references to his late brothers, John and Robert. He implored his audience to look beyond the fanfare of the campaign and instead toward keeping faith both in good and bad times. After quoting a passage from Tennyson’s poem “Ulysses,” Kennedy ended the speech with these illuminating words: “For me, a few hours ago, this campaign came to an end. For all those whose cares have been our concern, the work goes on, the cause endures, the hope still lives, and the dream shall never die.”

At the end of “The Dream Shall Never Die,” Kennedy received sustained applause and cheers from the crowd for half an hour. The New York Times editorial page noted that the speech w as “one of the greatest emotional outpourings of conventional history.” Today, “The Dream Shall Never Die” is known as one of Kennedy’s most famous speeches from his senatorial career and in modern American history, helping to lay the foundation for the modern Democratic Party platform. So successful was the speech that two of Kennedy’s three proposals were later accepted by Carter’s team — with these being the $12 billion stimulus package and a call for a jobs bill.

In contrast, Carter’s speech for the night was not nearly as successful as Kennedy’s. As Carter began to speak, a series of firecrackers were set off about 100 feet to his left by a woman named Signe Waller from the Communist Workers Party, causing the President to flinch and pause his delivery. After recovering, Carter made another serious blunder, referring to former vice president, senator and Democratic nominee for president Hubert Humphrey as Hubert Horatio Hornblower, the fictional protagonist of C.S. Forester’s popular series of novels.

Though the remainder of the speech went to plan, its ending once again did little to build support for the president. As Carter’s wife Rosalynn, Mondale and his wife Joan joined the president on stage, balloons scheduled to fall from the ceiling became stuck when the mechanism scheduled to release them malfunctioned. Only a trickle of balloons would end up working.

Unfortunately, Carter’s embarrassment did not stop there. While waiting for Kennedy to return to Madison Square Garden from the Waldorf Astoria Hotel, Robert Strauss — Carter’s campaign chairman — was forced to call various political figures onto the stage to keep the crowd cheering. Upon arrival, Kennedy and Carter came face-to-face on the convention stage. After Kennedy finished shaking hands with Rosalynn, Carter’s daughter Amy and Mondale, Carter moved to the center of the stage in front of the podium — a clear attempt to bring Kennedy with him so the two could pose for photos to present a united front. Kennedy refused to give in and stayed a few paces away from the podium. Carter tried again, this time extending his hand for a handshake, but he did so with his hand almost at shoulder height, inviting Kennedy to take his hand and raise it high. Though Kennedy stepped forward to shake Carter’s hand he refused to raise it with him. Instead, Kennedy chose to raise his own hand against the crowd alone. This continued four more times, and with each attempt, Carter was met with a curt handshake and polite dismissal. In front of more than 20 million television viewers, the President of the United States was found groveling for a photo with a man whom he had defeated.

In the end, the 1980 Democratic National Convention failed to unite the Democratic Party behind Carter — with the president eventually losing to Republican candidate Ronald Reagan in a landslide of 489 electoral votes to 49. The convention’s numerous blunders raised questions not only with regard to the merit of Carter’s candidacy but also the future of the Democratic Party’s policies.

Next check out New York City’s Presidential Haunts From Washington To Biden!

Subscribe to our newsletter